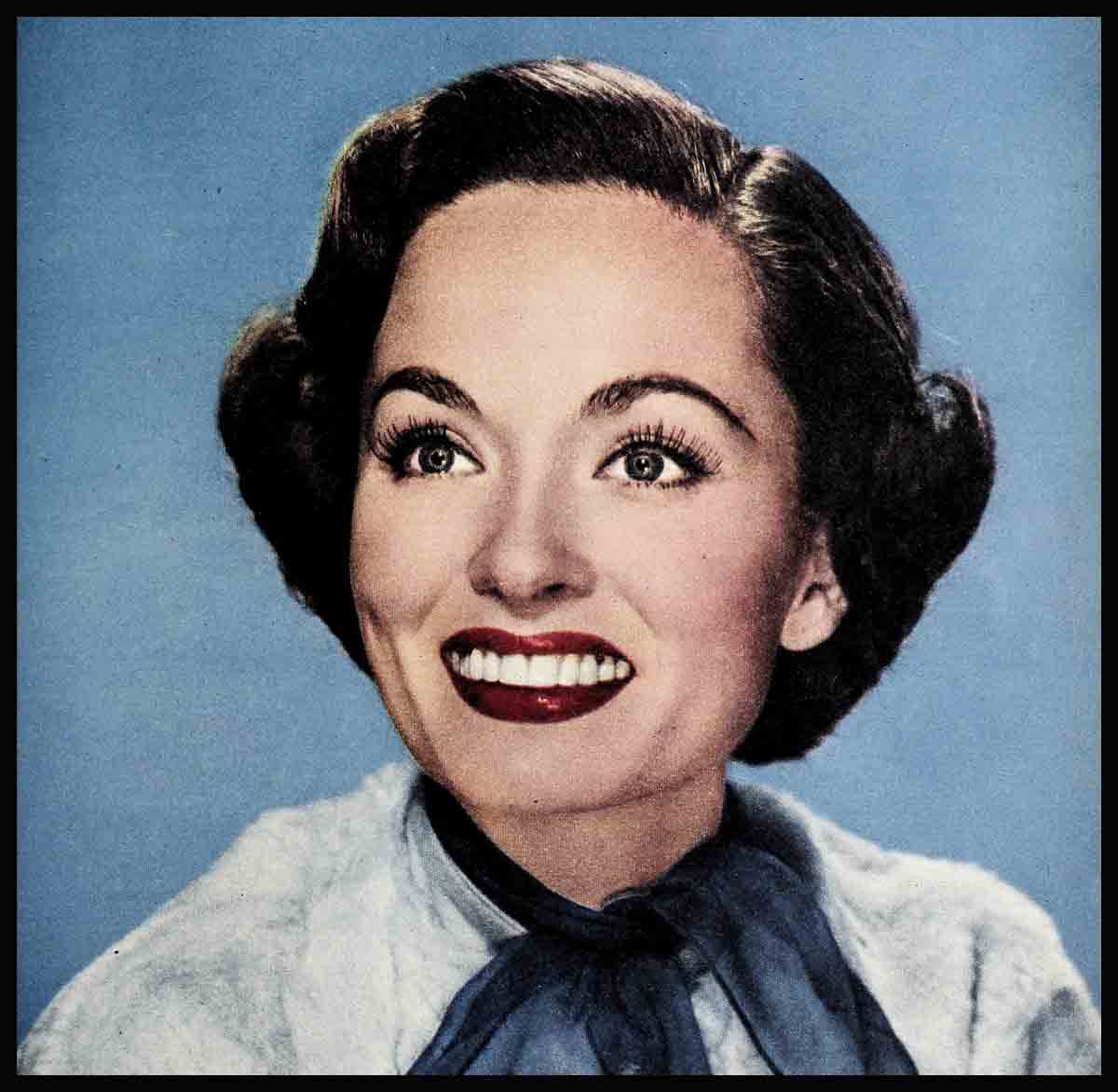

Just What The Doctor Ordered—Dr. James McNulty & Ann Blyth

One evening a few months ago, Dr. James McNulty, whose business is babies, excitedly called to his wife, “Ann! Come quick!” Responding, Mrs. McNulty found the doctor bending over their son.

“Look!” said Dr. McNulty in wonder. “Look at the way he’s got his fists doubled up. This boy’s going to be a boxer!”

Mrs. McNulty started to say, “I hope not.” But then she stopped, recognized that she was a little upset. She bit her tongue and smiled gently. “I wouldn’t be surprised,” she answered. It was then that Dr. McNulty looked up from his magnificent six-week-old son and caught the frown on Ann’s face.

“Is something the matter?” he asked gently. “Can I help?”

Suddenly with Jim’s kindness, his deep concern, Ann could no longer control her tears. She started to cry. It was all Dr. Jim’s and Timothy Patrick’s fault she felt like this. They had ganged up on her when she wasn’t aware and made it impossible for her to go along with her plans—despite the contract and the promises. Just a short time ago, the decision would have been easy. Now it seemed impossible. For during the past year, two men had entered her life—one helpless and lovable, the other, strong and loving. They had captured her love and run away with her heart and Ann had become dependent upon both husband and baby son. Instead of excitement, she felt discouragement over the prospects of her first night-club engagement. Las Vegas seemed a million miles from home and Timmy and Jim. She made up her mind; she wouldn’t do it, she couldn’t leave them.

“It’s funny,” she thought. “You are a person and you are happy by yourself and the way you live. Then you meet another person and fall in love with-him and marry him, and you are just exactly twice as happy. And after that a third person comes along, a very small one named Timothy Patrick McNulty and you are exactly twice as happy again. And then suddenly you realize that with all this happiness the many thing that used to seem so important before seem small and your big job now is keeping all your new happiness in good order.”

Some people—and not just in Hollywood, either—tackle wedded bliss with the mental reservation, “Well, if it doesn’t work, we can always get a divorce.” Of course, such people are quite correct in their assumption: they can get a divorce, and usually do. But to Ann and Jim the possibility of a divorce is simply inconceivable, and not solely because their religious faith forbids it. Their own personal faith—in themselves, in each other forbids it, too.

That kind of faith doesn’t come easily—certainly not from the simple act of falling in love. It comes from a good deal of living and growing-up, which both Ann and Jim accomplished before their marriage in June 1953.

Many little girls want to be actresses, but Ann made the dream a reality. From the age of five, when she sang and recited “The Chimes of Normandy” on the radio, she was a professional. It wasn’t easy. With her mother and older sister, she lived in a New York City cold-water flat. The family was very poor. To support Ann and Dorothy, and provide money for Ann’s singing, dancing and dramatic lessons at Ned Wayburn’s School, Mrs. Blyth worked in a beauty parlor, took in laundry, sewed late into the night.

Radio jobs came occasionally for Ann. Often, instead of a job she had hoped for, there was disappointment instead. But poverty and disappointment are not what she remembers best about her childhood. Rather, her memories are of her mother’s love, of abiding hope and trust in God.

In her early teens, Ann read successfully for a part in a Broadway play, “Watch on the Rhine.” The play was a hit, and after its Broadway run she toured with it across the nation. When it played Los Angeles, a talent scout from a major studio spotted her and offered her a contract. For two years, Ann was the sweet young thing in a series of quickly forgettable pictures. Then, against the objections of some who felt she lacked the dramatic fire necessary for the role, she was allowed to play the vixenish Veda in support of Joan Crawford in “Mildred Pierce”—and did such a stunning job that she was later nominated for an Oscar on the strength of it.

But it looked, shortly after “Mildred Pierce” was completed, as if Ann would never act again—nor walk either, maybe. Tobogganing with some friends in the San Bernardino mountains, she was thrown from the sled. She got to her feet and dazedly walked the rest of the way to the bottom of the run, unaware that her back was broken, with a fragment of vertebra actually protruding through her flesh.

For seven months after that accident, Ann was bedridden, in a cast. Doctors were unable to tell her with any certainty that she ‘would recover the use of her legs. Now she needed every bit of courage, of faith, she possessed—to fight the fear and the pain and the endless hours. Yet she said later, “I don’t think I ever really believed I would be crippled.”

Nor was she. After the seven months in a cast and another seven wearing a steel brace, she was able to once more to do all the things she loved—dance, ski, swim, bowl, play golf and tennis—and to take up her career where she had left it off. But fate had another bitter blow in store for her. She had barely started work on her first picture after the accident, when her beloved mother passed away.

You can’t undergo such experiences and emerge from them unchanged. In Ann’s case, they matured her beyond her eighteen years. After her mother’s death, she persuaded her Aunt Cis and Uncle Pat to give up their Connecticut home and live with her. She worked hard at her career, steadfastly avoiding the more hectic aspects of Hollywood social life. From time to time her name was linked romantically with that of some handsome young actor, and at first when this happened Ann would become so upset she would refuse further dates with the young man involved, for fear of giving gossip more to feed on. Later, she learned to accept columnists’ interest in her activities as one of the facts of Hollywood life.

But there were some other Hollywood “facts of life” which Ann never did accept. She was completely co-operative with studio bosses as far as attendance at benefits and premieres went, and with studio publicity departments for interviews and picture spreads, but she was seldom seen in the glittering night spots and lived her own kind of life—serene, unspectacular, centered around her home, her aunt and uncle and a few close friends.

She rather baffled Hollywood. Along with her sweetness—no one ever heard her say an unkind word or raise her voice in anger—she had an innate dignity that led some people to think her dull. They worried, or pretended to, because Ann Blyth had reached the age of twenty-four without being awakened emotionally. Ann herself was not in the least troubled about the state of her emotions.

“I always knew,” she told a friend shortly after her engagement to Dr. James McNulty was announced, “that I’d find someone like Jim. I was just waiting. Now I’m in love for the first time in my life and—oh, it’s wonderful!”

Dr. Jim could have echoed those words for himself. He’d been waiting, too. Nine years older than Ann, he’d been too busy to be serious about any girl. Medical school, six short months of private practice and then six long years in the Navy, followed by the stresses and strains of establishing a new practice in Los Angeles as a specialist in obstetrics and gynecology—all this hadn’t left him much spare time to devote to romance.

It would be wildly inaccurate to report that Ann and Dr. Jim fell in love with each other the instant they met at a Hollywood party. They liked each other, yes. Dr. Jim thought Ann was the most poised and beautiful girl he had ever seen; Ann thought he had the kindest, most understanding eyes of any man she knew. They talked; Ann knew and liked Dennis Day, Dr. Jim’s brother, and they had other mutual friends.

Five days later Dr. Jim called Ann to invite her to the christening of Dennis’ second baby. There she met the McNulty clan—Mom and Pop, Mr. and Mrs. Patrick McNulty, Jim’s sister Mary and his other brothers John, Frank and Bill. She admits to having noticed with some interest that of all the McNulty children, only Jim was still unmarried.

But it wasn’t until three years later that Dr. Jim asked Ann to be his wife—asked her on Christmas Eve, in the old-fashioned way with, ready in his pocket, a diamond ring he wasn’t completely sure she’d accept. Those had been three years when friendship and mutual respect ripened slowly, imperceptibly, into love; three unhurried years of learning that they liked the same things, thought alike on issues they both considered important, could laugh and play together or be quiet together with equal happiness.

Their wedding on June 27, 1953, was one of the most beautiful and impressive Hollywood has ever seen. Held in St. Charles Roman Catholic Church in San Fernando Valley, it was a double-ring ceremony presided over by James Francis Cardinal McIntyre, Archbishop of Los Angeles—the first time in Hollywood history that a star’s wedding has been performed by a Prince of the Church. Later, in the Crystal Room of the Beverly Hills Hotel, Ann and Dr. Jim received more than 800 guests at a champagne breakfast.

One of the guests at that breakfast told me, “I was never so sorry for any man in all my life as for Dr. McNulty. Photographers kept saying, ‘Look this way, Miss Blyth,’ and ‘Can you come over here, Miss Blyth,’ and nobody paid any attention at all to the groom. He was the forgotten man.”

When this remark was repeated to Dr. Jim, his eyes widened in honest surprise. “Why, I never gave it a thought,” he said. “Isn’t the bride supposed to be the center of attention at a wedding? And with Ann looking so lovely . . . Anyway,” he added, “I know how it is, Ann being a famous movie star.”

Which is precisely true, and one reason the McNulty marriage is on such a firm foundation. As Dennis Day’s brother, Dr. Jim is no stranger to the crazy world of show business. The demands of Ann’s career can neither surprise nor distress him.

Both Ann and Dr. Jim have a deep respect for the other’s work. During those seven months she spent in a cast, helpless and in constant pain, Ann learned to venerate the medical profession. To her, there is nothing quite so wonderful as a good doctor, with the knowledge and skill, his dedication to humanity. And she finds it specially satisfying to think that Dr. Jim’s branch of medicine concerns herself with the miracle of birth.

For his part, Dr. Jim is an avid movie and theatre fan. He is intensely proud of Ann’s fame, and once gently rebuked an acquaintance for intimating that his work was more important than hers. “People need entertainment,” he said. “A fine play, a beautiful song, a chance to laugh or even to cry—these are good. I’m glad Ann has the gift for bringing such pleasure.”

When “Gone with the Wind” was reissued last summer, Ann, who had seen it four times herself, discovered that Jim had never seen it at all, and they went together. Jim was fascinated, and afterwards they talked for hours about different scenes and the performance of the stars. For her birthday, a week or so later, Jim’s presents included a copy of the book—“I suspect because he wanted to read it himself!” Ann laughs.

Another present was a trip to Reno, to watch brother Dennis Day perform in a night club there. Jim was able to spare only a scant two days from his practice, but they found time to run up to Lake Tahoe, the scene of their honeymoon.

“This time, though,” Ann says wisely, “we kept out of the water. I think Lake Tahoe is the most beautiful spot in the world, but there’s no denying its water is horribly cold. Jim and I both love to swim, and on our honeymoon we put on our suits, walked to the end of the dock outside our cottage and simply dived in together. Oooh! It took our breath away. We didn’t even speak to each other—we couldn’t. We just turned around and climbed out as fast as we went in and that was the last of our swimming.”

What with the arrival of Timothy Patrick on June 10, just seventeen days before their first wedding anniversary, Ann’s career came to a temporary halt after completion of “The Student Prince.” It began again late in September with a three-week appearance at a Las Vegas night club—her first venture into this field of entertainment. And somehow that night-club engagement is typical of Ann; it sums up her attitude toward herself, her work and her marriage.

To begin with, she accepted it only after she and Jim had decided together. “Then when it come time to go, I couldn’t think of being away from both Timmy and Jim for three whole weeks,” she said firmly. “It will be bad enough being separated from them between weekends”—for of course Jim had already promised to to the Nevada city every Friday evening, his practice permitting. So finally Timmy went along with the nursemaid to whom Ann reluctantly confides his care when she must.

For her act, Ann dressed in exquisite but completely modest dinner gowns. Her program consisted of songs from her pictures, plus specially written material—some of it funny, some touching, some uplifting. In all of it, there was not one concession to the supposed sophistication of night-club audiences—which is to say, there was not one word Ann would have been embarrassed to have her own son hear, had he been a few years older.

And Las Vegas, which had loved Dietrich and Mae West, adored Ann. After her final performance she was given an ovation that was a spontaneous outpouring of affection and respect. Ann Blyth can come back to Las Vegas any time she wants to.

“I’m glad they liked me,” Ann says. “Awfully glad. But you see, I couldn’t have done a different kind of act. I couldn’t have been—well, flamboyant. That wouldn’t have been me.”

This personal integrity, this insistence upon being true to herself and what she believes in is Ann’s greatest strength, and her surest guarantee of continued happiness. All her life, she has wanted to be an actress, and she has achieved that goal. But success and fame are not her gods. She’s willing to work for them, and work hard, but she would never compromise, for the sake of her career, with her own sense of values. Important as her work is to her, Dr. Jim and Timmy and the other children she hopes to have are all more important. And will remain so.

THE END

—BY DAN SENSENEY

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955