Stormy Winters

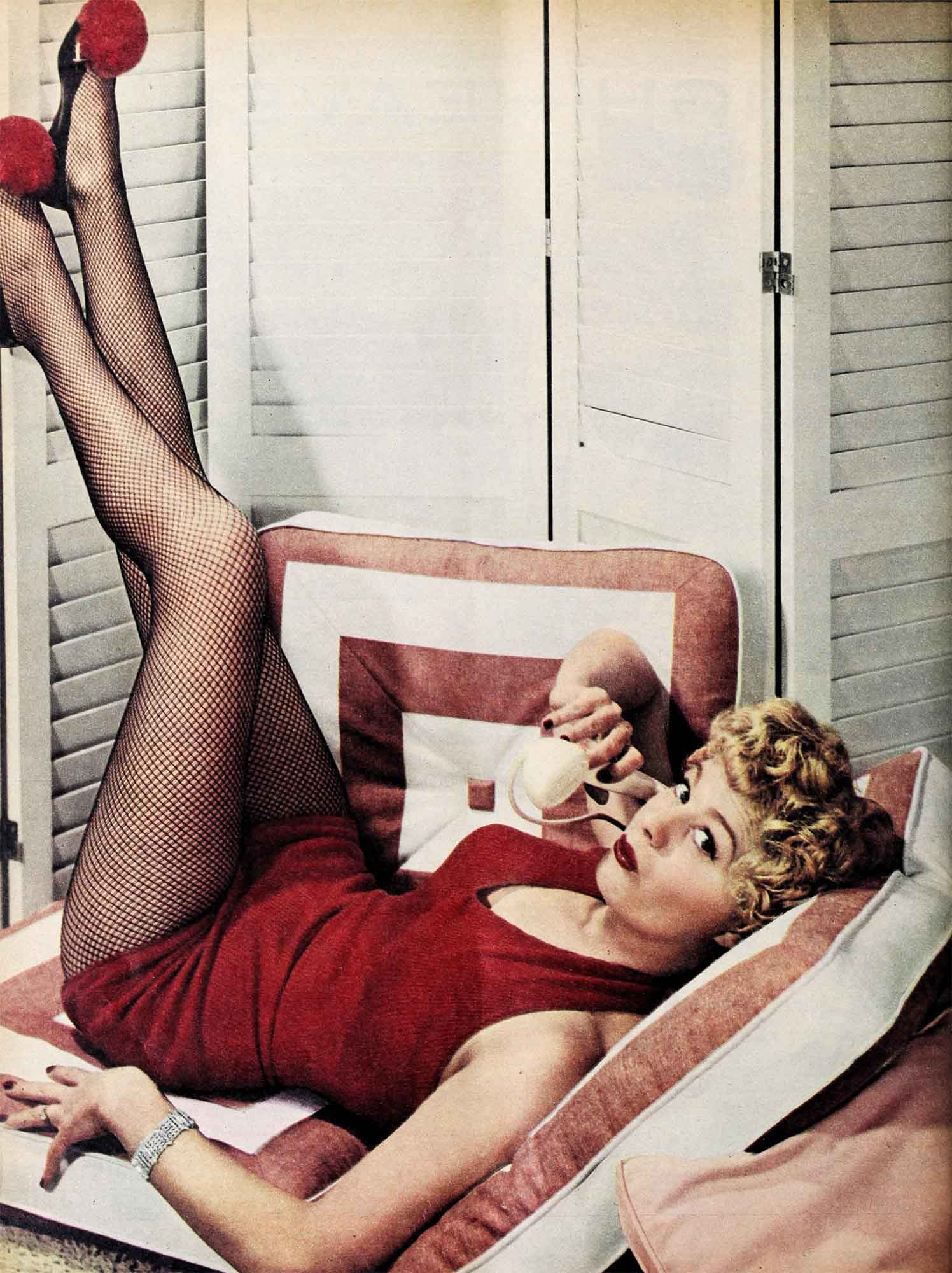

During the recent opera season, the music-lovers of Los Angeles were given quite a jolt. It wasn’t an earthquake, perennial L.A. jolter. It was Shelley Winters, dressed fit to kill, casually eating her dinner in the sixth row, while tubercular Mimi sang exquisitely to her lover Rodolfo.

“Farley loves opera,” explained Shelley. Farley, of course, being Farley Granger and her number one boy friend. “He had tickets for both of us for the entire deal. The night of ‘La Boheme’ I had to work late at the studio. Farley picked me up at 8:15 and brought along a couple of sandwiches and a thermos of coffee for me to have in the car. But he drove fast, and I was afraid I’d spill it on my new dress, so I just took my dinner in with me and hid it under the seat. I was so hungry, my stomach started growling. So I ate.” Next season, it is rumored, the lorgnette set may make opera-munching a fad. Shelley has found the cure for the stomach growl, long a horror of the music world.

Shelley’s the impulsive type. And ıt gets her into trouble. For some time now, off and on, there’s been a tendency among Hollywood columnists to rap Shelley across the knuckles. Success has gone to her head, they say. She holds up production. She is rude to the “little people,” which is tantamount to kicking your mother down the steps. One columnist, suffering from acute acidity, wrote, “Shelley Winters has a heart of gold, I am told. Maybe now that she is a success, we won’t have to dig so far to find it.”

In a way, Shelley does hold up production. “I always get tied up in knots when I start a scene,” she says. “I use any pretense to delay starting for a moment. I’m so frightened, I’m sick. Every scene with me is opening night on Broadway.”

Shelley’s definitely an eager beaver. She just plain loves to act. While most stars gripe like mad if they make two pictures a year, Shelley made seven pictures during 1949 and 1950 including loan-out for “He Ran All the Way.” When she suggested she be given a vacation after this picture there was great surprise. “What would you do with a vacation?” she was asked. “Study acting,” said Shelley. And study acting she did, in New York at the Elia Kazan Actors Studio.

She wants to be in every picture. Every time the trades or columns announce that so-and-so has been signed for such-and-such a picture, Shelley demands to know why she wasn’t offered the part.

Apropos of Shelley’s eagerness, when she was in New York some time ago, her representative, as a gag, told her that Sir Laurence Olivier’s agent was anxious to get in touch with her to discuss a part in Olivier’s next film. Shelley was agog. One of the boys in the New York office was in on the gag, kept calling her at her hotel, always when she was out. She was on pins and needles. One day, signals got crossed, Shelley was in her room. There was nothing for him to do but invite her to dinner. “Look, Shelley,” said her representative “this guy has an awful reputation. He’s a terrific wolf. Why, he’ll tear the dress right off your back.” “Okay,” said Shelley, “I’ll wear an old dress.”

It was this same eagerness plus grim determination that landed Shelley in her first “legit” play. It was in 1940, after she had worked as a salesgirl in a five-and-ten, modeled in department stores, played walk-ons in summer stock, and batted around generally. Chester Erskine was casting a play called “Conquest in April.” She charged upon him, one August day when he’d left the door open on account of the heat, and demanded a part in his play. She got it, but not until she’d worn him to a frazzle and borrowed money enough to join Equity.

Maybe it was the heat, maybe it was Shelley’s volatile personality that befuddled him. Anyway, the contract was signed before Mr. Erskine realized that if Miss Winters had appeared in all the plays she claimed to have appeared in, she would have had to be a member of Equity, already. When, later, he faced her with this, her comment was “Yipes!” “Conquest in April” collapsed in Philadelphia. But Shelley didn’t. It took her eight years, but she finally hit the jackpot.

Recently Shelley took inventory. In the three years she has been a picture success, she has bought her first mink coat, her first car, bought and furnished an apartment for her mother, and a home for her sister and herself. “And I still have money in the bank. As soon as I find time, I want to take a course in economics at UCLA. My salary is beginning to puzzle me.”

Shelley thinks she would like to get married again. “I don’t know if I really think that or if I just think I think that. But this I know. If I do marry, I would want to marry someone in the business. Wouldn’t it be a terrible bore to have to talk to someone every night who didn’t know what you meant when you mentioned ‘dissolves’ and ‘dolly shots!’ ”

Occasionally Shelley dates the field. But always she comes back to Farley Granger. He’s steady. When she started work on “A Place in the Sun,” the publicity boys tried to make something romantic out of her gab sessions with Monty Clift. But they didn’t get far. Monty and Shelley were only recalling their early struggles in New York.

Shelley’s marriage was not a very happy one. It was a wartime marriage and it didn’t work out. On New Year’s day of 1943, she married Mack Mayer, an Army officer, in New York, after a three weeks’ whirlwind romance. She was divorced in California in October, 1947.

At present, Shelley is on a dignity binge. Or she is pretending to be. She does not want to be called “scatterbrained” or “wacky.” “I prefer working at Paramount,” she told a group of U-I executives. “At Paramount everyone called me Miss Winters. Here, they call me ‘Stinky.’ There’s dignity at Paramount, in case you wondered what happened to dignity.”

When an interviewer, having been informed by her that she borrowed her name from her favorite poet, politely asked her the name of her favorite poem by Shelley, she haughtily replied, “Now you surely don’t expect me to answer that at one o’clock.” And then hastily added, with an evil glint in her eyes, “And don’t ask me at six o’clock, either.”

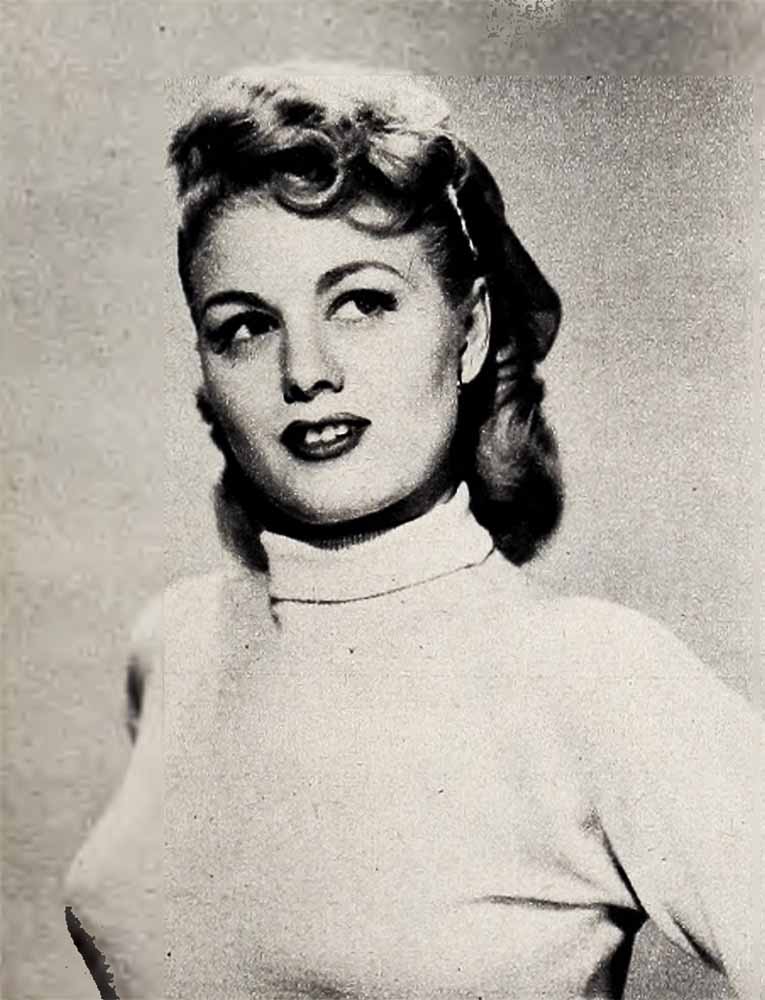

Shelley’s real name, for the records, is Shirley Schrift. She was born in St. Louis, August 18, 1923. Her mother was Rose Winters, an opera singer with the St. Louis Municipal Opera, and her father was Johan Schrift, a men’s clothing designer. The family later moved to Brooklyn.

The role that Shelley wanted most of all was the role of the mill worker in George Stevens’s “A Place in the Sun,” based on “An American Tragedy.” When a friend of Shelley’s suggested her for the part, Mr. Stevens very emphatically said, “Thank you, no floozies.” But he was conned into seeing several of Shelley’s pictures. Then he said, “Maybe.” By that time, Shelley was having the whim whams. After a series of tests, he gave her the part.

Shelley thinks that George Stevens is just about the best thing that ever happened to her. “With Stevens, it was like I went to school. I followed him around the set like a pest. Universal should have paid Paramount for letting me do this picture, instead’ of charging them.”

The pathetic little mill girl is a complete change from her former sexy roles. In the picture she wears no lipstick, no makeup, and she had her blonde hair darkened to a lusterless brown.

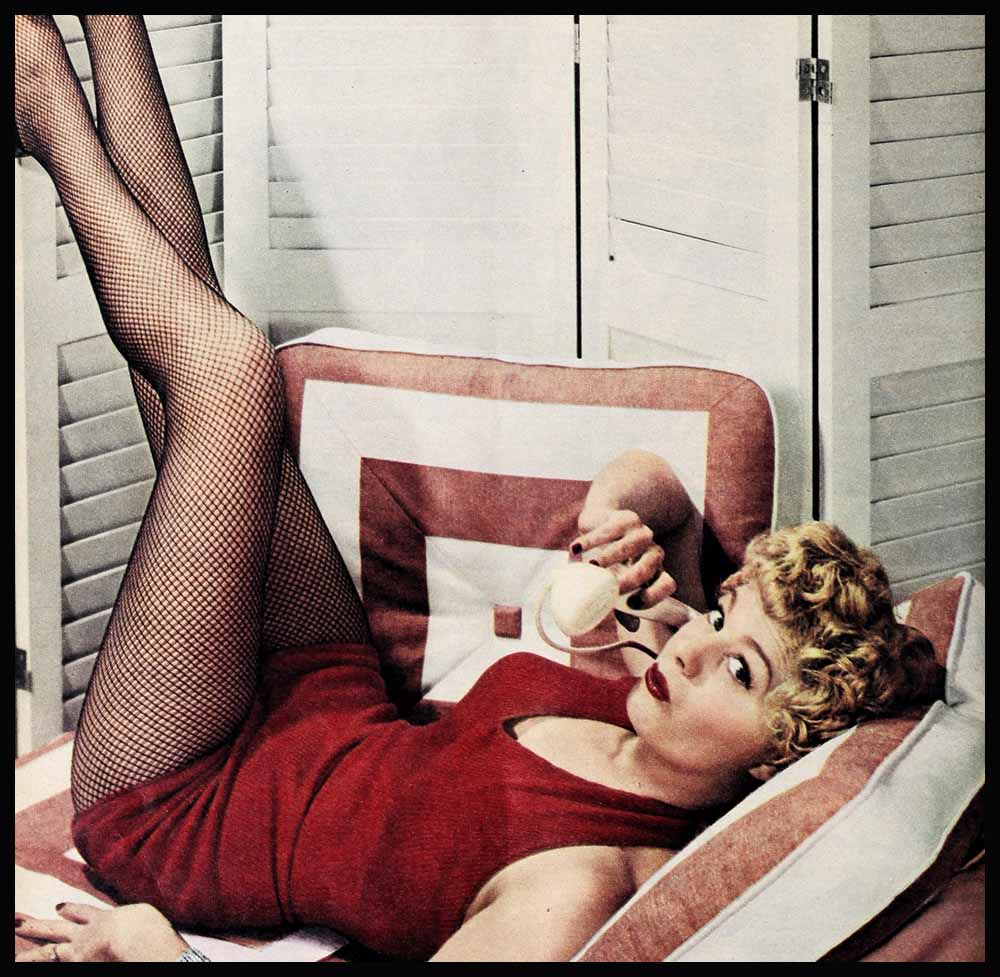

“In the future, I want to play human beings,” said Shelley. “But don’t get me wrong. I don’t think that sex should go out of the window entirely. Sex with dignity—that’s for me.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1951