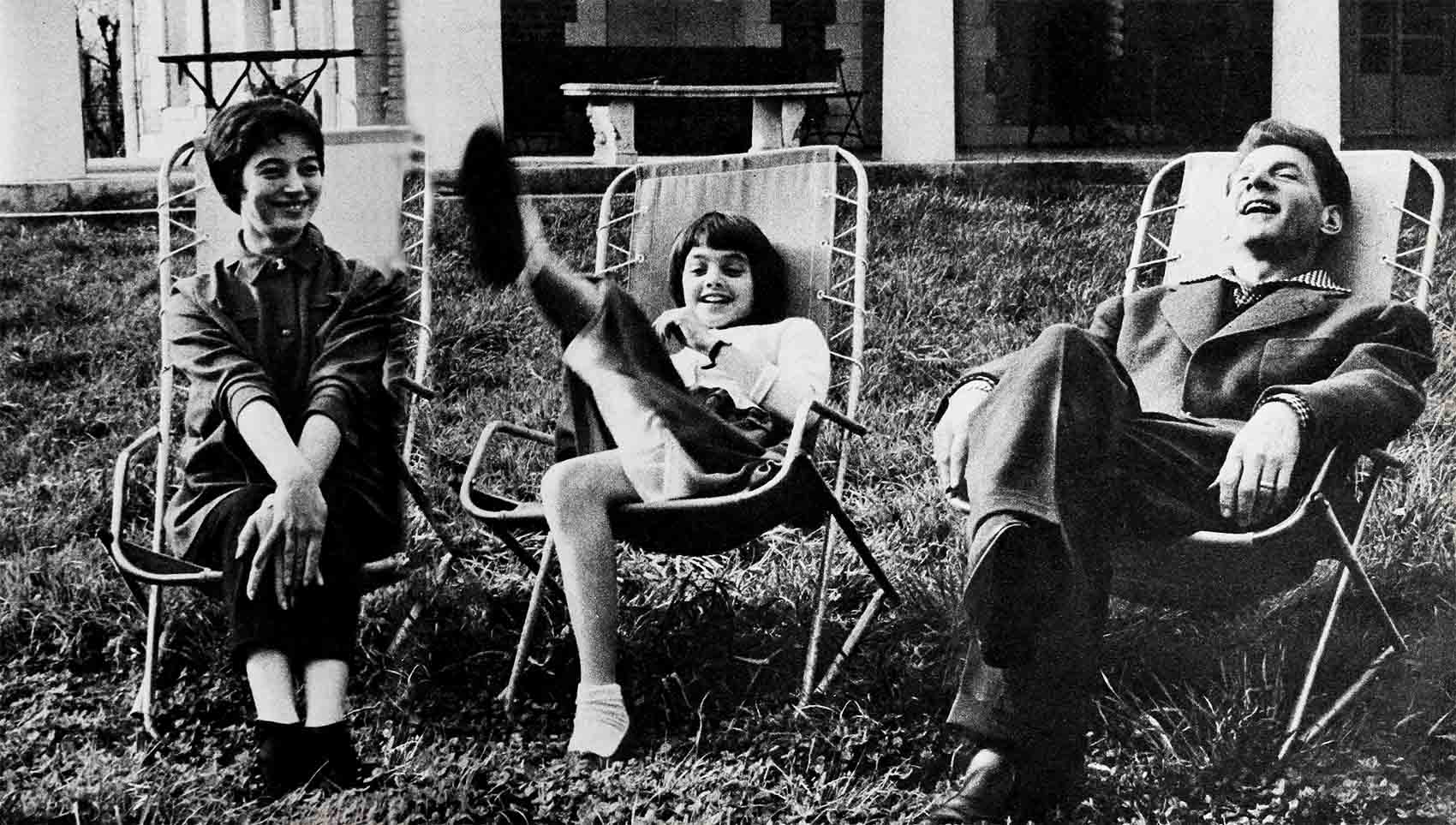

An Afternoon With Madame Aumont—Marisa Pavan & Jean Pierre Aumont

From Paris, it is a half-hour drive to Rochers, the Jean Pierre Aumonts’ splendid, forest-encircled villa in the suburb Malmaison. The last time I had seen Marisa was in California, before her marriage, and I was delighted to accept for Photoplay Marisa’s invitation to visit with her and Jean. As I drove up, the black iron gate was open in obvious expectation of a visitor. A cool drink had been set out on the wide terrace, which dominates the square Napoleonic-style house. A manservant with a musical Italian accent explained, “Madame and Monsieur will be here in a minute. They said you were to make yourself at home.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth when a minuscule French car shot jauntily through the gates and skidded to a stop on the driveway. Marisa Pavan and Jean Pierre Aumont, flushed and giggling like sixteen-year-olds, tumbled out.

“We’re late, I’m terribly sorry,” Marisa cried, “but we were out in the country. It was so lovely and peaceful we didn’t realize how time was passing.” Marisa looked at her husband, and the smile that passed between them showed exactly why they were late. A couple in love, walking hand in hand through a country lane—what does time mean to them?

Marisa led the way into the cheerful, sunny living room. Jean Pierre disappeared into the den for an animated discussion with a workman who was perched on a ladder, hanging new draperies.

“Please excuse the disorder,” Marisa apologized. “We’re in the midst of redoing the house. We’re changing the draperies in all the rooms, reupholstering the furniture, modernizing the bathrooms, and, of course, getting a nursery in shape for the baby.” She smiled joyously as she referred to the child she is expecting in late summer. “You know, there’s so much to do in a house after it’s been rented, to put it back into shape.”

The neglect into which Jean Pierre’s house had fallen was due less to the fact that he had rented it while he was in Hollywood than to the absence of a wife, whose love and care could turn it into a real home. Since Maria Montez’ death in 1951, Jean Pierre had lost interest in this house, where each corner held memories of the past.

But now everything had changed. Love had again warmed Jean Pierre’s heart as it had his home. Rochers had a new mistress.

Marisa took serious charge of the house in Malmaison upon their return from Hollywood last winter, after Jean Pierre finished M-G-M’s “The Seventh Sin.” She had barely unpacked their trunks when he reported to the Champs Elysées Theatre in Paris to rehearse the leading role in the play “Amphitryon 38.” He was already well into his part, because Marisa had helped him study his lines on the plane from Hollywood.

“As you may have noticed, I’ve selected gay tones for the draperies,” Marisa was saying. “I like stripes and bright, happy colors. Men are rather conformist when it comes to decoration, but I like to dare. Of course, Jean Pierre and I talked it over beforehand, as we do everything. He was in complete agreement with me on all my suggestions. But, if he hadn’t been, we would have reached a compromise plan. You see, we have tremendous respect for each other’s ideas.”

The utter simplicity with which Marisa made that statement emphasized the intense happiness glowing in her dark eyes at the mention of Jean Pierre’s name. She pronounced it with a caress in her voice.

Marisa had been transformed. Beautiful she had always been, but had she always had the sparkle of animation in her eyes, the aura of self-assurance that has nothing to do with vanity? These are the sure signs of a woman in love, who is loved in return.

Pride of possession illuminated Marisa’s face as she talked of Jean Pierre, and she was the first to admit she had changed. Until love invaded her life in the shape of this tall, blond charmer with the soft Gallic accent, she prided herself on her sense of independence and self-sufficiency. She was accustomed to look life straight in the eye, with rare objectivity and honesty. This gave her an inner sense of assurance, but heightened her outward timidity. A woman needs to feel loved in order to outwardly express confidence in herself.

“Marriage has given me a moral security and a goal in life,” Marisa stated simply. “I used to be fiercely on my own. I kept my problems and thoughts to myself. Now I have someone to lean on, to pour out my heart to, to share all my thoughts.

“I used to be very independent, much more so than my sister.” Marisa leaned back on the couch and curled her slacks-clad legs under her. Her expressive eyes, so like Pier Angeli’s, and yet so distinctly her own, held a faraway look. “Before Anna was married, she used to leave all important decisions to my mother. But I have always tried to solve my problems on my own. I had to. My mother was often away while Anna was making films abroad, and I had the responsibility of taking care of our house and our young sister, Patrizia. I used to take messages and keep track of correspondence and act as a sort of confidential secretary. Now Jean Pierre does all that for me.” Marisa laughed gaily.

“Then I decided to try my luck at acting. It was not an easy decision. I had developed a prejudice about the profession that I realize now was most unfair. I used to accompany my sister to the set very often, and I would say to myself, ‘What hard work this is! I could never do it.’ Quite often the press hinted that I was envious of my sister’s success. That is not true. I never felt that I was missing anything. I didn’t want to be an actress. I wanted to study languages and travel around the world to see different countries and study their civilizations.

“I was always very pleased and flattered when our friends would say to me, ‘You should be in the movies, too.’ I had registered at UCLA and was taking my studies seriously. I was beginning to relax a little, because I thought I had found my true destiny. But when I was given the chance to have a film test, I couldn’t resist. I had to meet the challenge and learn for myself if I had been wrong. And I soon discovered how exciting and stimulating acting is. I no longer had any doubts or frustrations about my career.

“Yes, everything was fine. My career was coming along very nicely. I had achieved more than I had ever hoped for in life. I told myself that quite often.” Marisa stopped speaking and began twisting the gold charm bracelet that never leaves her wrist. This bracelet is symbolic of her film success, each of the charms representing one of her films.

“Yet, deep in my heart, I knew I was fooling no one, not even myself,” Marisa said softly. “My success seemed futile, because I had nobody to share it with. Before I married Jean Pierre, I didn’t know why I was working so hard or for whom. Now that I have him and the baby we are expecting, my life is full. I no longer consider it a burden I have to carry alone.

“I must confess that I had always had a prejudice against marriage just as I had against acting,” Marisa smiled, rather sheepishly. “And I was just as wrong about it. This misconception stemmed from my childhood. My father had always been very strict, as most Italian fathers are. He ruled us all with a firm hand. I love my freedom and independence, and I imagined that marriage would mean the end of it. I looked upon marriage as a form of slightly enlightened slavery, with the wife at the mercy of her husband’s will, and all freedom of action impossible. Now I realize how terribly mistaken I was. Marriage can be a wonderful partnership between two people who love and respect each other.

“Jean Pierre and I each have our own responsibilities, of course, but we usually consult each other about them. He leaves all decisions about the house and servants to me, but I wouldn’t think of making any changes without talking them over with him. And that’s the way it is with everything—consideration of the other’s point of view. We may have rushed into our marriage—our families thought we should have waited—but we were both so sure, we said, ‘Why wait?’ And we knew the responsibilities marriage entailed.”

Marisa and Jean Pierre were first introduced to each other several years ago in Paris. He was appearing in a play, which Marisa had gone to see with Pier Angeli and a group of friends. Later they all went backstage to talk to him. The next day he called them up and invited the whole family out to dinner.

“I liked him instantly,” Marisa recalled. “He was so kind and well-mannered and so ready with delicate attentions. And I was filled with admiration for his intelligence and talent. But I never thought of doing more than admire him. I never dared imagine he could be interested in me. I had the impression he thought I was just a little girl, and for me he was as unattainable as a star in the sky.”

Three years passed, years in which the world was a witness to Aumont’s brief idyl with Grace Kelly. It was January, 1956. Marisa was making “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” at 20th Century-Fox, and Aumont was in a picture on the same lot. But they didn’t meet.

Then one night Jean Pierre went to a party where Pier Angeli and Vic Damone were also guests. Jean Pierre was seated alone in a corner when he saw Pier and Vic come in. He went over to greet them. “Where’s your sister?” he asked Pier.

“She’s home. She wasn’t invited.”

“Ah, we must do something about that,” Jean Pierre said. “Please give me her phone number.”

“I was posing for a portrait by an artist friend when he phoned,” Marisa recalled. “I was in an awful mood, depressed and blue. I had been in the dumps for months. Boys bored me; all I was interested in was my work. I stayed by myself and avoided social contacts.

“Then the phone rang, and my whole life changed. At first I thought it was a joke, that Anna had asked someone at the party to put on a French accent to fool me.

“I didn’t go to the party that night, but Jean Pierre and I talked on the phone for an hour. And I saw him for dinner the next night, and almost every night after that for two months.

“When he proposed—just eight weeks after we started going together—I couldn’t believe my ears. Oh, I was sure. I had been for so long. But how was I to know he felt the same way?”

Jean Pierre was sure almost the moment he met Marisa. He saw in her soft brown eyes the same need for tenderness and understanding that he himself had felt for so long, ever since the tragic death of Maria Montez.

That magnificent, volatile woman, whose memory is ever present in the person of their eleven-year-old daughter, Maria Christina, was as different from Marisa as it is possible to be. Spectacular and dramatic, her every gesture and movement made up a study in voluptuousness. Yet, oddly enough, Marisa, like Maria Montez, is a Gemini. Jean Pierre, who was born under the sign of Capricorn, is passionately interested in astrology. Not a day goes by that he doesn’t consult his horoscope and those of Marisa and Maria Christina. He asked Marisa to marry him because he loved her, of course, but he couldn’t have been more delighted when he discovered she was a Gemini.

Yes, Jean Pierre was sure, but he wanted Maria Christina to meet Marisa. He had promised himself that he would remarry only if his daughter approved of his choice. So he brought Maria Christina from New York, where she was staying with his parents. She and Marisa became fast friends almost instantly.

“Fortunately, I had plenty of experience with little girls Tina’s age,” Marisa was saying. “My baby sister, Patrizia, is just the same age, and I helped my mother to raise her. They are very different in character. Pat is soft and pliable, whereas Maria Christina is independent and stubborn. Whenever the two of them are together, they fight like wildcats, but they love each other.” Tenderness crept into Marisa’s voice.

“As soon as we were settled in the house, I outlined a program for Maria Christina to follow,” Marisa explained. “It was not that she was spoiled, but she had been used to having her own way a lot. A man who raises a child alone usually gives in to her. Jean Pierre agreed with me that she had to have some discipline, and he left it up to me.

“The first thing I did was to get a governess for her, an Italian woman from Rome, who speaks perfect French. Tina was often lonely, when Jean Pierre and I were busy, and it’s important for a child in her formative years to have someone as a companion. Her governess takes her to the Paris school she now attends, and picks her up later in the afternoon. She supervises her studies, and eats with her in the evenings, when I am in Paris at the theatre with Jean Pierre. And she sees to it that Maria Christina is in bed at nine o’clock sharp.”

Like any lively child with a mind of her own, Maria Christina often took advantage of her freedom when she was alone. She ate whenever she felt like it and had no set hours for her homework. Jean Pierre never had the heart to chastise her. But Marisa is getting her out of these habits.

“On weekends, of course, Maria Christina is home all day,” Marisa said. “One Saturday recently, she asked if she could have lunch with us. We usually lunch around three, as we sleep very late. I accompany Jean Pierre to the theatre most evenings, and we don’t return from Paris until late. Jean Pierre, of course, said yes, she could lunch with us, but I put my foot down. I pointed out to them both that three o’clock was much too late for a growing child to have lunch. Jean Pierre readily agreed with me, and now he doesn’t interfere with my efforts at discipline.

“Not that I believe in too strict training,” Marisa added hastily. “My own severe upbringing has made me more understanding of the need for leniency with a child. I believe that children should respect the judgment of their parents, but that parents should respect their ideas, as well. A home atmosphere of harmony and mutual love is the essential factor in the development of a child’s personality. The rest is of less importance.”

Marisa’s serious expression faded and was replaced by a soft smile as Jean Pierre strode into the room. He bent over the couch and kissed her on the top of her head. She reached for his hand and laid it gently against her cheek. “I’m going down into the village for the papers,” he said. “I’ll be right back.”

s he leaned to kiss her again, a plaintive voice came from the doorway. “And me?” cried the voice. We all turned our heads. Maria Christina, a startling image of her late mother, threw her schoolbooks on a chair, and leaped into her father’s arms. He hugged her tight. “And me?” cried Marisa. Jean Pierre freed one arm and gently lifted Marisa from the couch where she had been sitting. For the next few minutes the three of them hugged and kissed each other and danced around in a heart-warming display of Latin exuberancy. Jean Pierre finally extricated himself from his two ardent women and waved a hasty goodbye.

Maria Christina gave a graceful little curtsy (as all wellbred French children do) to Marisa’s guest, and announced that she was going to change her dress. Marisa agreed that that was an excellent idea, as we were having a grownup conversation.

“She’s quite a child,” Marisa said, looking after her affectionately. “She loves clothes, and we have great fun going to Paris to pick them out. Then in the evening she models them for Jean Pierre. We did have a serious dispute about her hair. She wanted a pony-tail, but she’s not at all the type, and I talked her out of it.”

Maria Christina suddenly stuck her head into the room. “Now you’re not to eavesdrop,” Marisa cautioned her.

“Oh, Mummy, I’m not listening to you,” the child answered. “I just wanted to know if Papa remembers he has to cut my hair today.”

I looked questioningly at Marisa, as she answered the child, who, satisfied with the reply, immediately left us alone.

“Yes.” Marisa answered my unasked question with just a trace of tears. “I see you noticed that she called me ‘Mummy.’ She started that spontaneously about three weeks ago. She used to call me ‘Marisa.’ Of course, Jean Pierre has noticed it, too, and neither of us has made any comment on it to her. I’m very touched. And she’s so excited about the baby. Of course, she wants it to be a boy. Every day she asks me, ‘Has it moved today?’ and if I should say, ‘no,’ she gets very worried and says, ‘I hope nothing has happened.’ ”

Marisa and Jean Pierre also hope it will be a boy, and they have his name already picked out: Jean Claude. If it’s a girl she will be named Ariane. They want the child to be born in the United States, so it will be an American, as Maria Christina is. That is why they are returning to Hollywood this summer, where Jean Pierre will probably make the new version of “Gigi.”

The Aumont household is trilingual. Maria Christina and Jean Pierre speak English as well as they do French, and address each other in both languages. Marisa’s French has vastly improved by lessons and her association with Jean Pierre’s French friends, and she prefers to speak in that language for practice. Their servants are Italian, and Maria Christina is learning Italian. “She corrects my French, and I correct her Italian,” Marisa explained. Maria Christina knows a smattering of Spanish also, as she spoke it as a baby with her mother.

The memory of Maria Montez is very much alive in this house in Malmaison, where she left the stamp of her powerful personality. Her picture is beside Marisa’s on Jean Pierre’s desk in his attic workroom, and on Maria Christina’s night table, next to her father’s and Marisa’s. “I encourage her to remember her mother,” Marisa said quietly. “We often look over family albums together, and she is very proud of the fact that her mother was a beautiful woman and a famous actress.”

Marisa sometimes has a mental struggle between her childhood training, which deemed that a woman’s place is in her husband’s shadow, and her own natural instincts for expression. But Jean Pierre is understanding, and she usually ends up by getting her own way. “We’ve had no serious disputes since we’ve been married,” Marisa said. “If we’re both feeling moody, we avoid each other until it’s over. If one of us is in a real temper, we talk it out together.

“We do have occasional discussions about clothes,” Marisa laughed. “For one thing, he thinks I have too many, but then doesn’t every husband? I like to follow the latest. fashions, but he disapproves. He thinks I should wear only things that suit me and forget about current styles. He likes me to wear close-fitting clothes with belts, and I like my things loose. Of course, during my pregnancy I have no other choice, and I’m delighted. One of my favorite outfits is a coat-dress I designed myself. It’s loose-fitting. When Jean Pierre saw it, he insisted I have a belt made to match. But when he’s not around I take the belt off.

“We don’t always agree about his clothes, either,” Marisa grinned. “I usually go shopping with him, but one day he bought some sport shirts by himself. They were awful, so gaudy and loud. He agreed with me and took them back.”

Soon after Marisa and Jean Pierre were married, he asked her to cut her hair. “With your delicate little face, you should wear it short and chic like a Frenchwoman,” he told her. So she had it cut close to her ears. “I must say it’s easy to keep up, but I feel so shorn,” Marisa sighed. “I prefer it just a little longer. Jean Pierre has finally come round to my way of thinking, and I’m going to let it grow a bit.”

Marisa and Jean Pierre share a love of music, painting and the theatre. She respects her husband’s superior knowledge of these subjects, and she listens wide-eyed when he talks about famous people. Having been a noted international star for over twenty-five years, he knows many personalities in the literary and entertainment field, and he has introduced them all to Marisa. But, with the exception of the Laurence Oliviers, who are Aumont’s best friends, most of their intimates in France are from outside the industry. They include Jean Pierre’s boyhood friends or buddies from his Army days, or members of his family. He and Marisa are very close to his brother, who is a movie director in France.

Metisa is an enthusiastic tennis player, Jean Pierre dislikes sports. But he patiently goes to watch her play, as he did recently when she had a match with Sir Laurence Olivier. His only hobby is writing plays, and it’s one at which he is a success. He’s had several produced in France and America. He and Marisa talk over his ideas before he begins working, and she takes real interest in both his hobby and his acting. During the run of “Amphitryon 38,” Marisa attended the play almost every night. When she wasn’t out front, she waited for Jean Pierre in his dressing room, to have supper with him.

Marisa has a determined nature, whereas Jean Pierre is rather easygoing. “I get tense and upset over minor things,” Marisa said, “but Jean Pierre talks me out of it and shows me how unimportant they are. I also have a jealous nature, but I have learned to hide and control it. I know that without mutual trust and confidence a marriage will never work.”

Marisa has succeeded in the dual role of wife and stepmother, despite her youth, because of her common sense and mature judgment. These are characteristics that also served her well when she was single and had to make decisions about her career. Now that she is married to a successful actor, she doesn’t hesitate to draw upon his fund of experience. He, in turn, is pleased that she seeks his advice.

“I don’t bother Jean Pierre about the business end of my contracts. I have a business manager who takes care of that,” Marisa explained. “But I do consult him about scripts.”

Marisa and Jean Pierre were in Paris last year, spending the last part of their official honeymoon with Pier Angeli and Vic Damone, when Marisa received the script of “The Midnight Story” from Universal.

“I liked the story very much,” Marisa recalled, “but I hesitated about accepting it. Jean Pierre had to stay in Paris to work out production details of the new play he had written, and he wouldn’t have been able to go with me to Hollywood. I didn’t want to leave him.”

They talked it over, and Jean Pierre convinced her to do the film. “Good scripts are so rare,” he told her. “It would be a pity to turn down this chance. This is our life, show business, and occasional separations are among the sacrifices we have to make. We might just as well get used to it. Besides, what are two months when we have our whole life before us?”

Marisa recently obtained her release from her Hal Wallis contract, and now she is free to take picture engagements anywhere. Since Jean Pierre divides his professional activities between Hollywood and France, Marisa will do the same, although she says that she would like to remain in Hollywood for a few years and really concentrate on her career. When they were first married, Marisa thought of giving up acting, but Jean Pierre was against the idea. “It would have been a shame to deprive the world of such a bright talent,” he told me. “Besides,” he added with a laugh, “I’ve made fifty-seven pictures, and Marisa’s only made eight. She should have a chance to catch up.”

“I’m certain I can keep on with my work without neglecting my husband and home,” Marisa said. “But if I see any signs of my marriage being threatened because of my work, I shall give up acting. My idea of happiness is not based on fame or financial security or success, but on love. It is the sole reason for a woman’s existence, the answer to everything she wants.” Marisa’s voice softened almost to a whisper. “Love is so precious to me that I don’t like to discuss it out loud, any more than I pray out loud.”

But Marisa’s whisper can reach the ears of the one person who has the right to hear her, Jean Pierre. “For me, she is Juliet and Portia, Ophelia and Scarlett O’Hara, Peter Pan and Antigone, all wrapped up in one,” he says. “And yet she is so essentially herself, with her secrecy, her poise, her mysterious charm, her depth—in spite of her youth—her intelligence, her kindness, her honesty.”

She is all this. And she is also a woman who is in love.

THE END

—BY MARY WORTHINGTON JONES

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957

No Comments