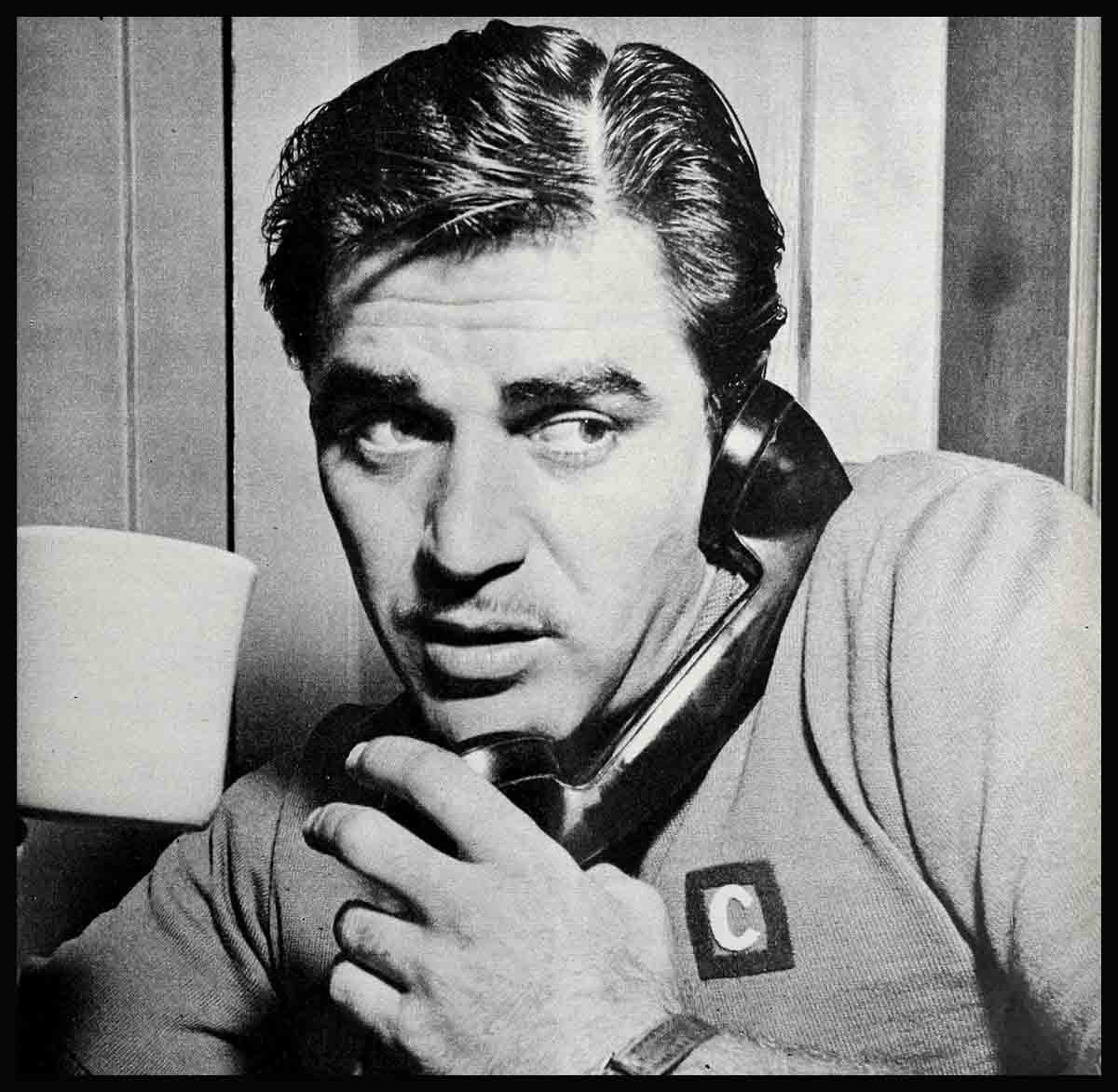

Lonely Lochinvar—Steve Cochran

The house where Steve Cochran lives crouches, somewhat apologetically, under a frowning hill. Facing Yoakum Drive, a street which Steve himself describes as little more than a wide ditch, it merges into its background naturally. It could be the property of a workman in an airplane factory or a gardener, but it certainly would never be pointed out as the home of one of Hollywood’s most important young male stars. And this is precisely why it suits Steve Cochran right down to the ground.

Now well launched on a career which he has pursued long and devotedly, Cochran, at first glance, does not seem the sort of person who would choose a nondescript house. A bachelor—young and handsome enough to titillate the heart of most any young woman—he looks like the kind of male who’s most in demand in a community that’s hungry for eligible males.

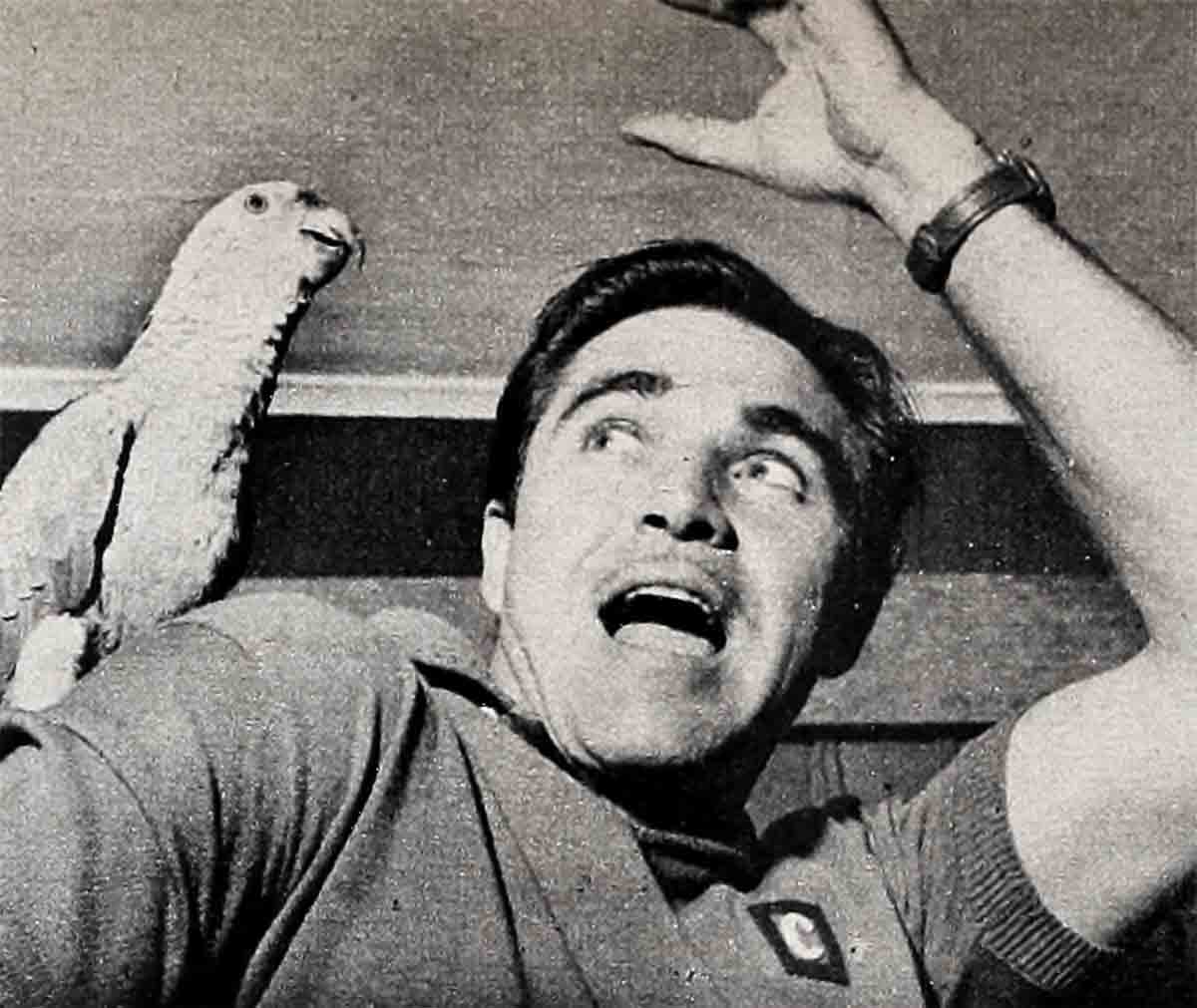

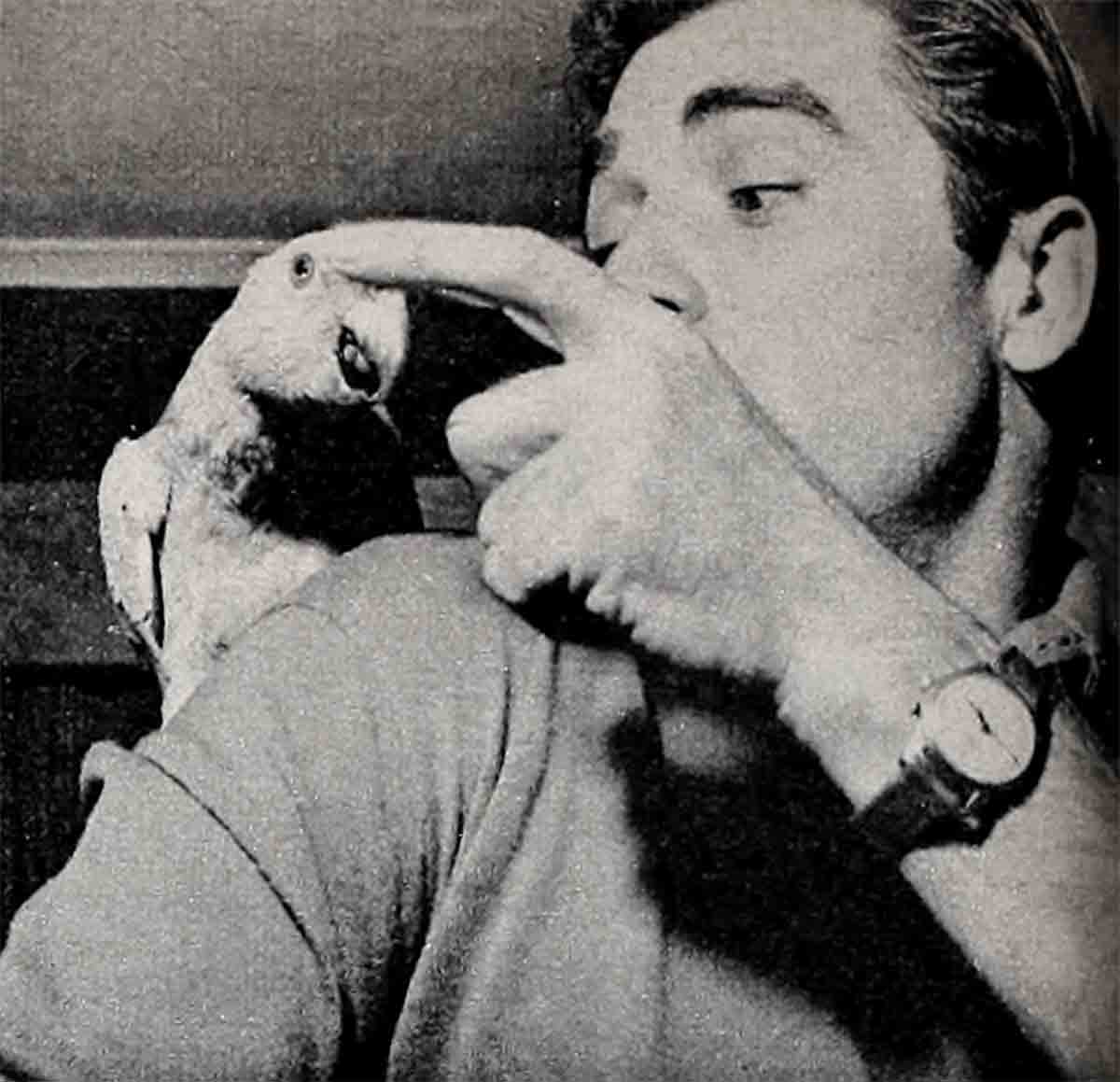

But Steve conducts his life exactly as he chooses—and this does not include much of the kind of gaiety Hollywood is famous for. Almost any cool California evening when he’s not working, he can be found sprawled in front of the huge stone fireplace in his library, his legs stretched out to a log blaze, a book in his hand, Tchaikovsky, his dog, curled up at his feet, and his parrot, Clarence, hovering in the background. He’s proud of the fact that he’s often alone, and he wonders how anyone could be lonely when there are so many good books waiting to be read. But his door is never locked and people, all sorts of people, wander in at the most improbable hours.

When he does get into a restless mood, he prowls from room to room, reciting a passage from “Richard III”—imagining himself playing it as well as, or better, than John Barrymore did. Or he cooks up his favorite dish, spaghetti and meat balls, which he can make on an overheated flatiron in an emergency—a talent left over from precarious stage days. Now and then he sings in a rather rich baritone voice.

For all his ability to get along well by himself, however, he is no hermit. He loves a tough poker game—with men only—and plays, as he does everything else, to win.

Six feet tall in his socks, built like a wedge with wide shoulders, slim waist and the easy carriage of a boxer, he looks considerably younger than his thirty-six years, He dresses negligently but with considerable taste when he’s away from Yoakum Drive, but at home he prefers to be comfortable in jeans or slacks and open-necked shirts.

Cochran’s casual manner toward himself and life is, no doubt, a hangover from the days when he tried almost everything to ensnare an elusive dollar. He was, from time to time, a ranch hand, a fireman, a shipyard worker, railroad laborer and just plain hobo.

“I learned in jungle camps and working on a section crew that no one is very important,” he says. “You meet some rare philosophers around a camp fire on a railroad right-of-way. If you thought you were good there was always some grizzled veteran to take the conceit out of you. But I found gentleness and consideration among those tough-whiskered vagrants more often than I have since I pulled myself a few rungs higher up the ladder we call success. And most of all, I learned never to take myself, or life, too seriously.”

If you ask him why he decided to become an actor, Steve grins. “We were living,” his story goes, “in Eureka, California, the town where I was born. My father was a lumberman, an easy-going man with an itching foot. He suddenly decided, one day, that he would like to take a look at Denver, Colorado. So he loaded the family—mother, my sister Vina and me—into an old Model T Ford and we started out on a roundabout journey. On the Wyoming prairies we got caught in a blizzard—and ended up in Laramie. Dad liked the place, got a job on the U. P. Railroad and Vina and I started school.

“It was during high school in Laramie that I got bitten by the acting bug. I’d broken training rules on the basketball team and they threw me out. I simply had to do something, so I went in for dramatics. I guess I fell in love with the sound of my own voice. Anyway, I never did get over it.”

During summer vacations Steve worked as a general hand on a ranch. He got fifteen dollars a month with room, board and rolling tobacco thrown in. “I wanted to save thirty dollars,” he recalls, “the price of a pair of hand-tooled, high-heeled boots, but by the time I’d amassed this fortune I didn’t need ’em. My legs were as tough as any leather.”

He finally decided, though, that staying on top of spooky broncs and playing nursemaid to a bunch of steers didn’t pay off very well, either in money or future prospects. And it did seem that a little more education wouldn’t do any harm. That fall he matriculated at the University of Wyoming, handicapped by a still-mending broken arm (the result of misjudging a pony that sunfished when it should have crowhopped) and a colossal lack of all kinds of useful information. At the end of the year, with spring turning the sagebrush around Laramie to soft grays and greens, restlessness seized him. He pooled his resources with another stage-struck boy, a dancer, and they headed for Detroit, Michigan, where Steve had heard there was a little theatre that welcomed new talent.

But the little theatre manager was cool to their offers to put the enterprise on its feet. He said something vague about experience and turned away. They wangled several other interviews, but they all ended the same way. The boys had sworn they were going to “act or starve” and it looked as though the choice was about to be made for them. They had a solemn council on ways and means, and after concluding that they were the only sane people in Detroit, they decided to separate and divide their capital. Steve’s share was seventy-five cents and with that in his pocket, he hopped a slow freight train for Flint; there, he had heard, fortunes were being made in the sale of patent medicines.

“But that dream blew up,” Steve said. “I couldn’t stand talking about people’s ailments and their insides. So I got a job selling vacuum cleaners.”

With his engaging boyish smile, he found it easy to persuade housewives to listen to his sales talk. The trouble was that he couldn’t keep his prospect’s attention on vacuum cleaners. Motherly women plied him with questions and often wound up asking him to stay for dinner. These invitations compensated, a little, at least, for his appalling lack of orders. Sometimes after a meal was over, the woman’s husband would have Steve go over his sales talk again, criticizing and offering suggestions. “But they never, never bought any cleaners,” Steve said.

Once a middle-aged man opened the door and listened attentively. The young salesman’s spirits rose. Here, at last, he told himself, was an order. At last, when he was out of breath, the man began asking searching technical questions about the construction of Steve’s cleaner, questions that couldn’t be bluffed or evaded. When Steve could no longer dream up answers, he began making unfavorable comparisons between other machines and the one he was selling. His prospect then led him down into the basement and showed him a whole roomful of cleaners. He turned out to be a professional repair man! “Don’t ever knock the other fellow’s product, son,” he said, “and learn all there is to know about your own.”

“Of course I didn’t make a sale,” Steve says now, “but that nice fatherly fellow taught me a lesson I’ll never forget. His advice holds good in pictures as well as in vacuum cleaner sales.”

His vacuum cleaner career ended when the sales organization decided it had been advancing Steve expense money long enough without any orders in return.

So he decided all over again that he was simply a natural-born actor and it would be a shame to deprive the stage of his gifts any longer. Once more he laid siege to casting offices. The directors, unfortunately, continued to stare at him as if he had just crawled out of a stack of alfalfa. He was on the verge of slinking back to Laramie with his belt tightened to the last hole when, suddenly, he was given a chance in a Federal Theatre Project in Detroit, where “The Road to Rome” and “It Can’t Happen Here” were playing. He started to eat again, and he hung on until the shows closed.

In 1937, he made his first attack on Hollywood. There, as usual, all the talent scouts ignored him with enthusiasm. Convinced, at last, that he was a hay shaker at heart, he was about to start for the freight yards in search of a hospitable box car, when Eddie Elsner offered him the lead in a little theatre play, “There’s Always Juliet.”

When that hopeful venture died, Steve returned to Laramie. He decided that he was going to be a little theatre producer himself. He gathered a bunch of show-struck kids about him and put on “East Lynn” and “Ten Nights in a Barroom.” They sold beer and soon auto-loads of customers came pouring into the converted barn which they used as a theatre, shouting and hissing at the villain and cheering the heroine. One customer, an elderly lady, called Steve on the telephone. “I can’t afford all ten nights in the barroom,” she said. “Which one would you recommend?”

In 1938 Cochran was back in Hollywood, battering at studio gates. But he needed more than a charming smile and a pleasant manner to get through those portals. At last, in desperation, he turned to directing children’s plays. One of his students, older than the others, attracted his attention. She was Florence Lockwood, the daughter of a portrait painter. “You know how kids are,” Steve muses. “We were both dedicated to the thee-tuh and, of course, ‘kindred souls.’ I suppose we fell in love. Anyway, we got married.

“She’s in Carmel now, with our ten-year-old daughter, Sandra. Our marriage didn’t last very long. How could it? Young dreams fade out and harsh reality intrudes. Marriage isn’t kid business.”

As to future marriage plans, Steve says, “No I don’t think I shall ever marry again. I’ve got what the psycho-couch boys call a mental block. Oh, it’s not an absolute decision. If the time ever comes when I feel that the whole thing must be untangled, I’ll do it. Of course, I’m not satisfied with my life. Let’s just say that I’m content with my present marital status.

“Most people think that ‘now’ is ‘forever,” he philosophizes. “It isn’t. Life moves on, conditions alter, the thoughts that once were long, long thoughts in the heads of youngsters change. Ideals and beliefs shift and wear a different face and there isn’t any way of stopping the change. I’m always impatient with writers who glorify youth. Kids don’t have a very happy time. They’ve vulnerable and everything that hits them hurts.”

Soon after his marriage, Steve went to Carmel and started a barter theatre, but it seemed doomed to failure from the beginning. When the enterprise collapsed, he joined forces with Denny and Hazel Watrous who were then staging a Shakespearean festival in the open-air Forest Theatre in Carmel. Steve was cast in “Twelfth Night” and “Macbeth.”

After that he shuttled between San Francisco and Hollywood, vainly attempting to associate himself with some producing company with a financial future. But nothing materialized. Finally, he went East for a season in stock with the Greenwood Theatre at Peak’s Island, Maine. When this folded, he took a job firing a steam engine in a sand pit near Del Monte. Then, with callouses on his hands as thick as the sole of a boot, he returned to Hollywood for one last try. Again, he was universally ignored.

At this point and for the umpteenth time he almost determined to leave the theatre as flat as it had left him. But he took one last cool look at what he had to offer first. And he was convinced—all opinions to the contrary—that what he had to offer was worth having. He decided to give acting one more chance. With the munificent sum of six dollars in his pocket, he rode the rods to New York. There the unbelievable happened! He landed a lead in “Without Love,” which was to go on the road after closing on Broadway, with Katharine Hepburn and Elliott Nugent. Soon producers appeared bearing contracts. Samuel Goldwyn took an option on his services.

Playing the lead in the play, he finally arrived in Los Angeles where Goldwyn exercised his option. He was in the movies, at last. He appeared in “Wonder Man” and was Danny Kaye’s ring opponent in “The Kid from Brooklyn.” Next, he was featured in Goldwyn’s “The Best Years of Our Lives,” and went on to play the leads in such pictures as “White Heat,” “The Damned Don’t Cry,” “Storm Warning” and many others. He himself is as pleased with “She’s Back on Broadway,” and with “The Desert Song,” both of which he made under contract to Warner, as with anything he’s ever done.

And he’s just finished a loan-out assignment for Universal-International, which is a radical departure from his previous roles. It is called “Back to God’s Country” and Steve is enthusiastic about it.

You wonder, as he talks about it, if Steve Cochran has ever found his own “country.” One would guess that he hasn’t. Men like Steve rarely express the strong, tough emotions knocking about in their own hearts. And yet, to such men, the future always beckons. For Steve, tomorrow is another day.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1953