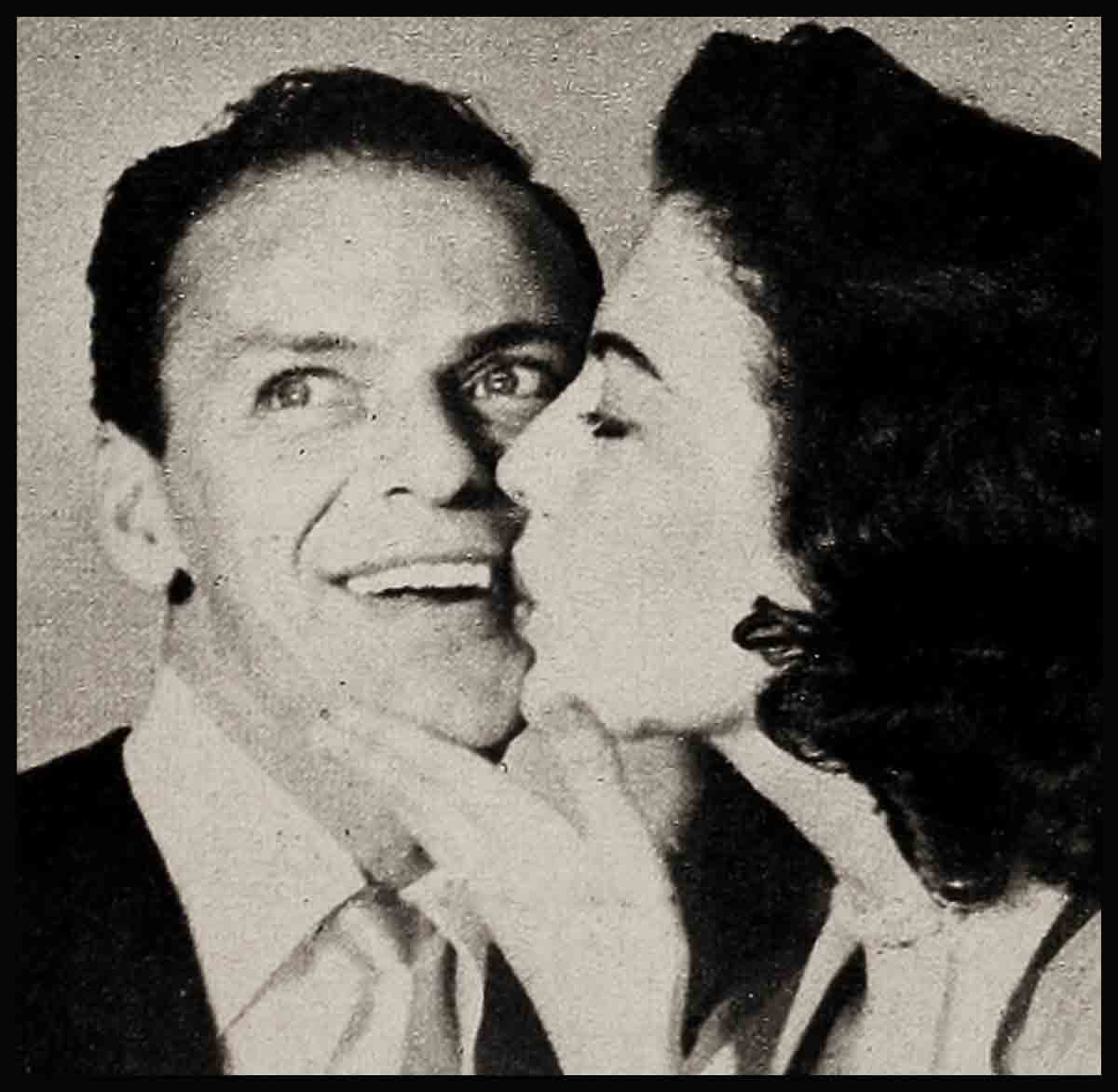

Hollywood’s Most Passionate Loves—Ava Gardner & Frank Sinatra

The passion of Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner, born in a confusion of bad publicity and intrigue, may seem headed for certain disaster.

Look at the odds against them. For nearly two years Sinatra courted Ava in the goldfish bowl of glaring publicity.

His excitable nature turned on newspaper reporters assigned to cover the romance in Hollywood, Mexico City and Madrid. His resultant bad press underlines the theory that when the press is against you, you can’t survive unscathed.

The public failed to flock to Frankie’s first post-Ava movie Meet Danny Wilson. Apparently as a result, Universal-International cancelled another picture he was to make for them. He lost a second part at 20th Century-Fox. On top of that, CBS dropped his television show.

Later, Sinatra went back to New York to accept another television show and vaudeville appearances. And, behind him, to encourage his climb back to public favor, was Ava.

This is the girl who surprised everyone by weathering his irritable temper and his fights with the press, by withstanding sharp criticism against herself, and by encouraging him when his career took a temporary nosedive.

Ava, her close friends believe, is the strong partner in this marriage. If it survives, it will be largely because she had the courage to be psychoanalyzed.

On a psychiatrist’s couch, Ava sorted out her emotions and learned to understand people, and, most of all, herself. Without that understanding, the marriage might not have been possible.

While Frank still may be torn apart inside by tensions, his beautiful wife appears serene with a deep inner content.

It’s strange to think that any movie star could be so troubled as to seek psychiatric advice. Movie stars are supposed. to be poised, confident, desired, loved, rich, famous and therefore happy.

Not many are. Most, in fact, have more trouble finding emotional security and a stable, secure marriage than any other group of people in the world.

Ava was driven by unhappiness to an analyst because she was too afraid to face her daily life. She had been unable to find happiness in her marriages—to Mickey Rooney and Artie Shaw—or her fabulous movie career.

It might be presumptuous to speculate on the basic reasons for her unhappiness, because they are probably known only to Ava and her analyst. It is true, however, that at an early age she developed deep feelings of insecurity and inferiority that made her unable to find her place in the world.

Ava was one of six children. Her father was a tobacco grower near Smithfield, North Carolina. She helped pick tobacco and cotton in the fields. Usually Ava ran around in her bare feet. She still does.

For whatever the reasons, Ava became sensitive about her humble beginnings. Later she became unhappy when she found she wasn’t ready to step up into a higher level of society.

She had lived her early years in an isolated community. Meeting strangers frightened her. When she was sent to a school in Newport News, Virginia, Ava was awe-stricken. She had never seen such a big city.

On the first day of school, Ava got up like the other pupils to give her name. When she said, “My name is Avah Gahdner,” the whole class laughed. Ava says she now understands they were laughing at her North Carolina accent, not at her, but at the time she was crushed.

Ava was terrified on her first date. She couldn’t think of anything to talk about. So on the way home, she read all the road signs aloud. That boy didn’t ask her out again.

Once Ava was playing on a woman’s basketball team at school and was sent into the out-of-town game as a substitute. She found herself with the ball and with the eyes of the crowd upon her. She made a score—but in the opposition team’s basket. Her humiliation was so severe that years later, when she returned to that town to enter college, she was embarrassed. She was sure everyone in town would remember her mistake.

“When you are driven by fear,” she said recently, “every molehill becomes a mountain.”

She never finished college. At 18, as movie fans well know, she won a bid to enter the magic city of Hollywood after her brother sent her photograph to an executive at MGM.

But the little girl from North Carolina didn’t fall happily into the glittering life of ease, parties and swimming pools.

When she went out on dates and to partes she was shy and often uncomfortable.

“I was so afraid they’d laugh at my Southern accent that I began to talk in a whisper,” she once said. “I felt I didn’t have the right clothes, either. Everything I wore seemed to look wrong. My dresses weren’t like what the other girls had on.

“I didn’t know how to read a menu, or how to order a meal. I didn’t know which fork to use. At my first big dinner party I watched my hostess like a hawk to see which piece of silverware she’d pick up next, When the butler brought the finger bowl I didn’t know what it was for. I was in a panic.

“I often left parties early, not because I was bored, but because I felt lost. I was afraid to talk or ask questions for fear of exposing my ignorance.

Ava married twice in her early twenties, perhaps to find some security. But she was not happy. She still felt inferior.

On the set of The Hucksters, her first big starring role, she was paralyzed at the thought of acting with Clark Gable. For her first scene she was supposed to walk through a revolving door toward him. Her legs felt frozen with fear. When she finally got through that door, she fluffed her lines over and over. The director at last called a recess and she crept into a corner in panic.

Ava decided she did not know true happiness, and sought help through psychoanalysis. Facing the fact that she was dissatisfied with her life, she started on the road to emotional security. She frankly admitted that she was unable to cope with the situations which produced certain fears. She wanted to find out why she was afraid.

Analysis was her search into herself. It took nearly two years, and it wasn’t easy. It was painful for Ava to relate her problems and fears. But all the money and time in the world could not pay for what it brought her—peace of mind.

Analysis taught her that she couldn’t run away from her fears—that laughing and trying to be gay doesn’t help.

“I learned that people accept you for what you are, no more, no less,” she says. “To put on an air of phony sophistication doesn’t do you any good.”

To advance her education, Ava went to UCLA to study such subjects as economics and literature. “It’s wonderful to meet people,” she says, “when you have something to talk about—and when you have freedom from anxiety and can express yourself.”

Five years ago, Ava would have been sick with fear at the thought of flying to Spain to star in Pandora And The Flying Dutchman. But now, she happily discovered that she made friends all over Europe with persons who liked her, and liked being with her.

Ava also had discovered through analysis that her two marriages failed because she was emotionally immature. She decided she never would marry again until she felt adult and satisfied with herself.

When Ava met Frank, she at last felt all that. Before Frank, Ava had met many men she could have married . . . men who were “right for her.” But she wasn’t ready. She wasn’t “right” yet for herself.

Ava felt grown-up, relaxed and free from anxiety during the first months of her passionate romance with the slender crooner. They settled into a relaxed, warm relationship. And Ava knew—realistically and without frantic “in love” emotion—that she now had the capacity for a marriage that would last.

Ava, her friends say, had many a talk with Frank about controlling his temper. She vigorously denied that Frank behaved disgracefully towards the press, and claimed she was “fed up with all the lies that have been written about us.”

A friend explains, “She’s trying to help his confidence by sticking up for him.”

Ava recently met me in her dressing room at MGM. She wore only a sweater and skirt, but she looked glamorous, anyway. She appeared radiantly happy as she talked of her marriage.

“It’s great,” she said. “It’s the only way to live. I never did like being single.

“Frank and I have problems to work out together, of course. Every married couple does. But we intend to work at them. Marriage takes a lot of adjustments and compromises. Life is one big adjustment, and marriage is the biggest of all.

“We want children,” she smiled. “I used to want six, but I’m too old now. I’m 29 so I’d better settle for two or three.

“I’m very happy now, because I feel I am mature enough for marriage. I never was before.”

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1952

No Comments