Hollywood Never Looked Better

Home sweet Hollywood. Or was it? They’d be landing any minute now, but from San Bernardino the ceiling had closed in below them. And where were those lights of home he’d missed so long?

Rock Hudson was disappointed. More disappointed than when—after bucking a blizzard in Iceland and twenty hours of headwinds across the Atlantic—his plane had landed at Idlewild Airport in New York and the field there, city-side, had been closed in too. Just a lot of country. No lights. Nothing but heavy darkness.

“How do you feel about the ‘warm’ welcome in England, Rock?” reporters had asked. “What about those hot protests British Equity made about you starring in ‘The Sea Devil’ over there?”

This he could answer.

“How does it feel to be home, Rock?”

This he couldn’t. “Great,” he’d said. And then the growing lump in his throat w as answering for him. . . .

Now they were going through the clouds, and there she lay—The City of the Angels shimmering brightly down below—a jeweled welcome for him. “There’s Atlantic Boulevard!” he called out eagerly, with an enthusiasm that the ex-trucker once named Roy Fitzgerald certainly never thought he’d feel while viewing Atlantic Boulevard from any angle, having delivered too many loads of dried beans thereon. But what a thrill now. He knew every curve, every green light.

About green lights, this ex-trucker from Winnetka, Illinois, felt he knew plenty anyway. Those lights down there now—in a way they spelled the story of his life. And a lot of them had been green. Like a pin-ball machine, he thought. If you’re lucky and connect, the whole thing lights up for you. No longer are you a trucker delivering budget-packed macaroni and dried beans.

You had to leave, to know just what you’d won. To know just how much this moment meant—coming home.

Four years. Had it been just four years since a husky 197-pounder fresh out of the Navy reported for work at the Budget-Packplant on the east side of Los Angeles? His dad had gotten him into the truck-drivers’ union, and he’d been sent out on the job. Sixty dollars a week minimum. More for over-time. And some way or another, there was usually over-time. He bunked in a boarding house on Sixth Street right off Wilshire, sharing quarters with three other guys for sixty dollars a month including meals. A fellow could do a lot of traveling in Los Angeles County alone.

But his was not the heart of a trucker. All the traveling Roy Fitzgerald wanted to do, was across town to those motion picture studios. Ever since he could remember, he’d wanted to be an actor. As a ten-year-old back home in Winnetka, he’d haunted the movie houses, really dreaming it up big. He couldn’t shake the dream and as he grew older he’d tell himself, “Well, who knows? Maybe some day I can.”

And once in California, it soon developed he could. Henry Willson (who later became his agent), then a talent executive at Selznick-International, became interested through some photographs Roy mailed to the studio. He arranged for him to take dramatic lessons from the Selznick coach, Lester Luther, every chance he got.

Chances, he made. Let him have a load of macaroni or beans bound in the general direction of Culver City—and whist—Fitzgerald would be parking his truck on a side street by the studio, and soon be inside sounding off with such weighty speeches as Death’s in ‘‘Death Takes a Holiday,” no less. What with his blue jeans and work shirt with the trucker’s button pinned on, Jennifer Jones, Joan Fontaine, Joe Cotten and other stars thought he was another laborer. And in a way, an important way, Roy Fitzgerald was. From the first, he has been eager to work.

Some of those lights way over to the right, he thought, might be Warner Brothers. How well he remembered the day he’d gone there for an interview with Director Raoul Walsh who put him under personal contract for one hundred twenty-five dollars a week—and a guy named Rock Hudson was born. Later Raoul had directed the screen test, a sexy scene with Janis Paige, that got him a contract at Universal-International—that would be a little to the left. There, a lot of talented people had helped make him a star. There, Walsh had directed him in his favorite role in “The Lawless Breed”—and Rock knew then that he would cheerfully follow him, if necessary, into the briny deep. And he’d followed him across it to England for RKO’s production of the Victor Hugo classic, “Toilers of the Sea,” retitled “The Sea Devil,” in which Rock co-stars with Yvonne De Carlo.

How he’d missed the gang on his home lot! Some of them would still be straggling home now. Soon Rock would be one of them, with his red Olds convertible heading for the Freeway as though trained—then up to the redwood-and-glass modern home shining on its own little hill. He could imagine his setter, Tucker, waiting joyously to blitz him. Almost smell the aroma of fresh coffee his mother, Mrs. Joseph Olsen, would have merrily perking.

How he’d missed this house with its two walls of glass that welcomed the whole San Fernando Valley inside. Missed watching the purpling mountains in the distance. The spaciousness of it all. Missed living so close to the sun and sky. You had to leave to know how much. In a homesick mood one rainy London evening, he’d tried to describe it to a new British friend. “Everything’s so—so—open—back home. There’s so much living room.”

In London, particularly at first, Rock had felt all closed in. Those old flats with their high ceilings were like living with history. But the past has color of its own, he found. The old, old doors with their brass knockers polished so bright a man could see himself in them had charm too, a charm quite different from the glass-and-chrome shimmer he was used to at home.

One thing sure, Rock Hudson, if anybody cared, could now write a book on what a Hollywood Yank should know—and expect—when traveling abroad.

What to do with excess baggage, for instance. It seemed so simple: he’d pack a trunk, have it shipped, take a few things in a bag along with him. At the last minute, he’d borrowed a trunk from the studio, stayed up all night packing it, then just before leaving for the plane he’d called somebody to come pick it up. “Do you have the necessary papers?” a voice asked impersonally. “What necessary papers?” he repeated, feeling like a straight man. That was his cue, and he speedily started tossing things out of the trunk and into every suitcase he could find, taking all of them along with him. Never would he forget the surprised expression on the British producer’s face when Rock put the bill for two hundred and fifty dollars excess baggage into his extended welcoming hand.

Nor had anybody reminded Rock of the difference in time. Nor had he reminded himself. That was the shortest night of his life—going over on the plane. He’d awakened to find the sun shining in the window and heard somebody say, “It’s eight o’clock.” As he shaved, he wondered why he was so groggy and tired. Must be the high altitude, or trying to jack-knife his six-feet-four into a sleeping position. When finally he looked at his own watch, it was just 2:00 a.m. New York time. Just three hours since he’d gone to bed. He’d lost a lot of sleep.

As a matter of fact, he was even then beginning to feel a little lost all over. “I just can’t describe it,” he wrote home. “I wonder if any man can. That feeling. Seeing your last sight of the United States—the Cape Cod coastline—disappearing behind you. Such a lost feeling—I can’t tell you.”

He’d landed in England in a cold freezing rain, and consistent with the general pattern, of course, in all that excess baggage, no raincoat. Rock wondered then if a Yank ever got warm in Britain. Now he knows. They don’t!

Nor when traveling is the customer always right. “Any cigarettes?” the British Customs man asked right off. “Oh, yes,” Rock smiled companionably. “I brought along six cartons.” “Well, two cartons are all right—but the others—you’ll have to take them out, or pay duty on them,” the man said. A delayed take and then, “How much?” Six pounds, seven shillings, and four pence; seventeen dollars and eighty-two cents in American money.

The Customs officer, he could understand. No mistaking what he said. But for a fellow whose own grandfather came from England, and who himself was one-quarter English, Rock had his difficulties interpreting others.

Food rationing was no worry. The little inn down the road from the studio, an hour and a half out of London, always had fresh eggs that farmers nearby brought in. Back home, Rock was strictly a steak man, but with eggs, chicken and pheasant, who could complain? Particularly since the British people themselves were too ready to share whatever they had with him. When a waiter named Dave at the Dorchester, where Rock stayed, would spend his day off fishing and bring back six trout saying, “These are for you, Sir.” How could a man top this?

Which had given Rock the nod to go into the kitchen and demonstrate how coffee was entitled to be made. For some reason, any negotiations involving coffee seemed a complete mystery to the British. As Rock had discovered immediately upon landing there. At a restaurant, he’d said casually, “I’ll have my coffee now,” and found that in England, one doesn’t get one’s coffee until after the meal. Later, he was to wonder at this particular waiter’s courage in serving it, though demitasse-sized, at all. To a coffee-connoisseur like Rock, who downs king-sized cups of it all day long at home, it lacked everything.

All this prompted the interesting conjecture that with coffee alone, British Equity might appreciably discourage American actors from coming over. For in Rock’s case, the British union protested—and in headlines—against a Hollywood star being brought over for a role in a movie made there which, in Equity’s opinion, an English actor was better qualified to portray. However, even as his pals back home burned over those headlines, Rock, comfortably quartered in a cottage in the peaceful little village of Gorey on the Island of Jersey on location, making love to Yvonne De Carlo before the cameras, was oblivious to any criticism. He was personally feeling no pain.

Weeks later, when he returned to London and reporters cornered him for his reaction to the matter, he said, “What matter? There aren’t any newspapers where I’ve been.” To friends back home in Hollywood, he quickly made it plain, writing: “The English people don’t resent us. It’s just a matter of Equity, wanting to protect its own actors. The people here are great. For instance—take the Queen—”

And on that subject, if Equity had protested there were actors who could better have managed the impressive bit of an American being presented to Queen Elizabeth at the Command Performance, Rock himself would have been the first to acknowledge it. This ceremony too, he’d failed to familiarize himself with, back at dear old New Trier High.

All the actors were briefly rehearsed, of course, on protocol over there. They weren’t to speak to the Queen “unless she speaks to you.” They were not to shake hands with Her Majesty. Just hold her hand briefly and bow. But as Rock explained later, “I was so frightened, I forgot all the rules.” Before he knew what he was doing, he was shaking hands with the Queen. He bowed, straightened up, and sometime later, when Her Majesty didn’t move on, he realized he’d frozen onto her hand for dear life. But she’d been most charming. “I understand you’re making a picture over here,” she said. “Yes, Your Majesty,” they were making “The Sea Devil,” Rock somehow managed to answer. “That’s good. I hope you’ll come over again,” she smiled, disengaging her hand.

How unfortunate that a few could give so wrong an impression—that the English are antagonistic towards American stars. On the contrary, Rock found the British people very concerned about whether or not Americans liked them. At the first general press conference, soon after his arrival, when a reporter asked the usual, “What is your impression of England?” Rock answered honestly and innocently, ‘I’m impressed mostly by your people”— and soon found himself in trouble.

“I’ve been told English people are very formal with strangers—that sort of thing— and I came over expecting that. Instead, I find you thoroughly charming,” which most of them accepted appreciatively. But one reporter had a chip on his pencil. “Oh, don’t Americans like the English?” he said, ready to make an issue; and a headline. “Certainly—but well, most of them haven’t been here. They don’t really—” Rock was going on, when he stopped, with an expression of pained surprise. Standing near him, Yvonne De Carlo, who’d been through such interviews in many lands, had kicked him thoroughly on the shin.

Rock was surprised to find that the British knew him. But he shouldn’t have been. They’d seen “Scarlet Angel” and “Bend of the River.” Loyal fans awaited him every night outside his hotel, and one, a pretty eighteen-year-old girl, come rain or more rain, would always be there. Hers was a never-ending vigil, and the night before Rock left, she said, “Here,” and shyly put a gift, a beautiful lighter, into his hand.

About British girls in general anyway, Rock Hudson had no complaints. None whatsoever. They were as nice as could be, he decided. None of the big intrigue. No guessing games. And with complexions like milk and honey. In Britain a woman depends upon a man, which, in Rock’s opinion, is the way the Lord meant it to be.

Actually, no matter how one looked at it, it’s a small English-speaking world, he decided. Passing a small record shop one day, he was surprised to hear “Basin Street Blues,” good and loud and jazzy and American. Going inside to say “Hello” to somebody from back home, he found, instead, a typical British Oxford man—striped morning pants—derby—the whole works, even to the spatted tapping toe.

“Like that music?” Rock grinned.

“Rather,” the fellow said.

“How come?”

“I went to Northwestern University at Evanston, Illinois,” he explained. He’d heard a lot of American music those days.

“That’s just three miles from my hometown, Winnetka!” exclaimed Rock.

“You don’t say. I used to go with a girl who lived there,” the Englishman said. “Gloria Balaban. I was engaged to her while in college.”

“You don’t say?” grinned Rock. “I went steady with her at New Trier High.”

A record enthusiast himself, Rock bought some of Vera Lynn’s platters, including the one appropriately titled, “The Homing Waltz.” He bought Wedgwood china for his mom, four suits for himself—and where else could one get so handsome a topcoat for seventy-five dollars?

But on the other hand . . .

Where else could one find a husky guy measuring six-foot-four, who could get so homesick? Funny what a guy misses when he’s away from home. Like “Dick Tracy” and his favorite radio and TV programs. Miss the programs? He even missed the commercials!

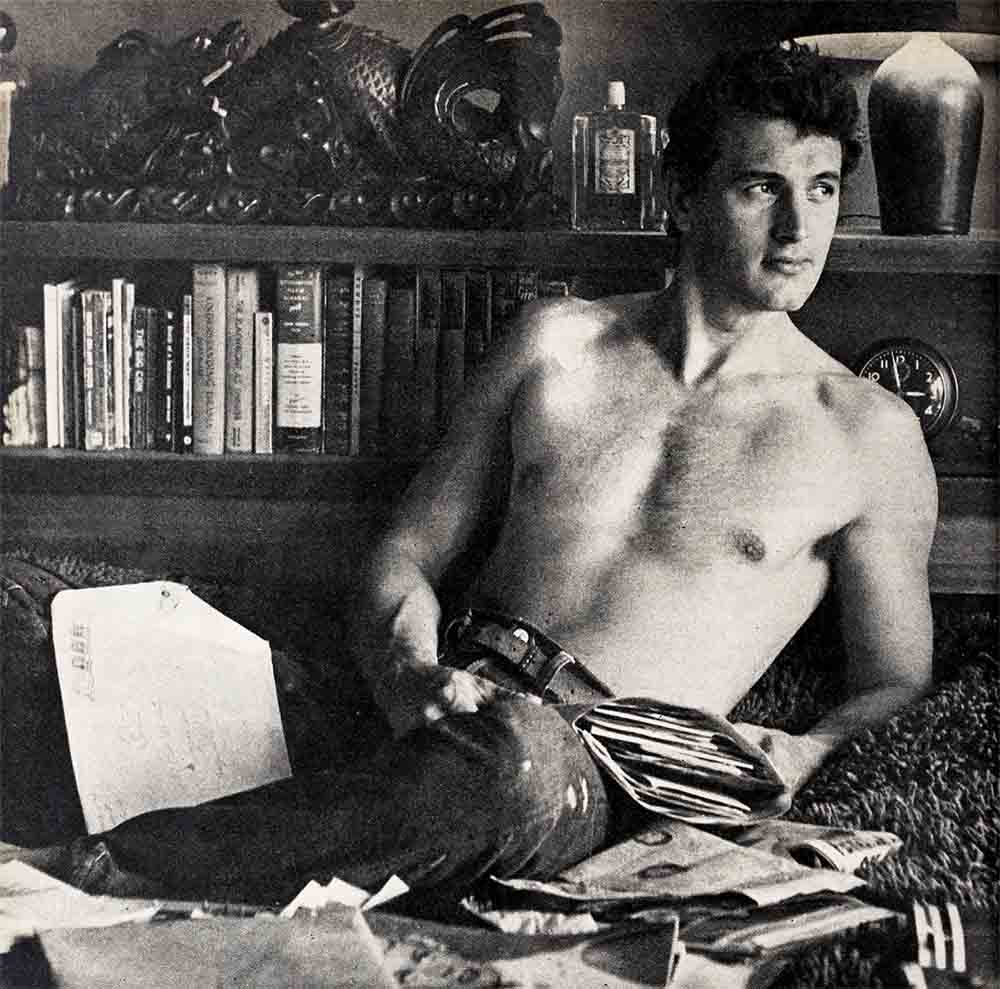

He missed going bowling in the evening. Taking a squint at the warm morning sun and streaking to State Beach at Santa Monica for a swim. In England there was no swimming closer than Brighton, eighty miles away, that is, if you were an Eskimo. He missed seeing Americans driving British M.G.’s, and driving them on the right-hand side of the road. Speaking as a southpaw himself, a left-hander driving on the left-hand side of the road, Rock had managed to create a honking pandemonium in England most of the time. And how he missed his own informal kind of living! Relaxing in blue jeans and his favorite red sport shirt when he got home from the studio, with his record player going, fresh coffee percolating. Or just sitting, with his white-socked feet propped up on the coffee table, philosophizing away the weightier problems of the world.

“Poor Rock,” some of his pals commisserated, when U-I called him home so suddenly. He’d been promised three weeks of sightseeing in Europe when he finished his picture overseas. But due to a switch in casting, Farley Granger was out of “The Golden Blade,” an Arabian fantasy which co-starred Piper Laurie, and Rock Hudson had been hurriedly called home.

Poor Rock! A phooey and a pshaw!

Let others see those Pyramids along the Nile. The way he felt right then, he’d rather see them on a Universal sound stage. He’d take his fantasy in Hollywood. Where else could a truck-driver named Fitzgerald travel across town and realize the dream of a lifetime?

There, below him now, was all the magic a man could use. And every light spelled a message and memory—welcoming Rock Hudson home.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1953