Planning A Heavenly Love Nest—Rock Hudson

“As far back as I can remember,” Rock Hudson mused aloud one day, “I have lived in other people’s houses—never in a place I could call my own. But now, at last I have my own house, a place where I feel I can put down roots, where I can belong.”

But, exciting as that home and that time was to be, there was a second installment due on the story. An installment even Rock didn’t dream was in the cards for him on that spring day in 1955, when he was so excited and so enthusiastic about the first house he was ever to own. Sure, he knew that someday he’d marry. It was as much a part of his plan for the future. as having a home of his own, of traveling extensively, or someday, he hoped, having children.

At the time, however, Rock’s thoughts were still concentrated almost wholly upon his career. And the girl in his life, at the time, was script girl Betty Abbott. They were just good friends, but publicity had blown it up, as Rock angrily said, “into a ‘thing.’ ” Because of this, all talk about his personal life came to an end—as far as publication was concerned. People even said that Rock had pretty much settled down to his bachelor life in the ranch-type house high on a hill.

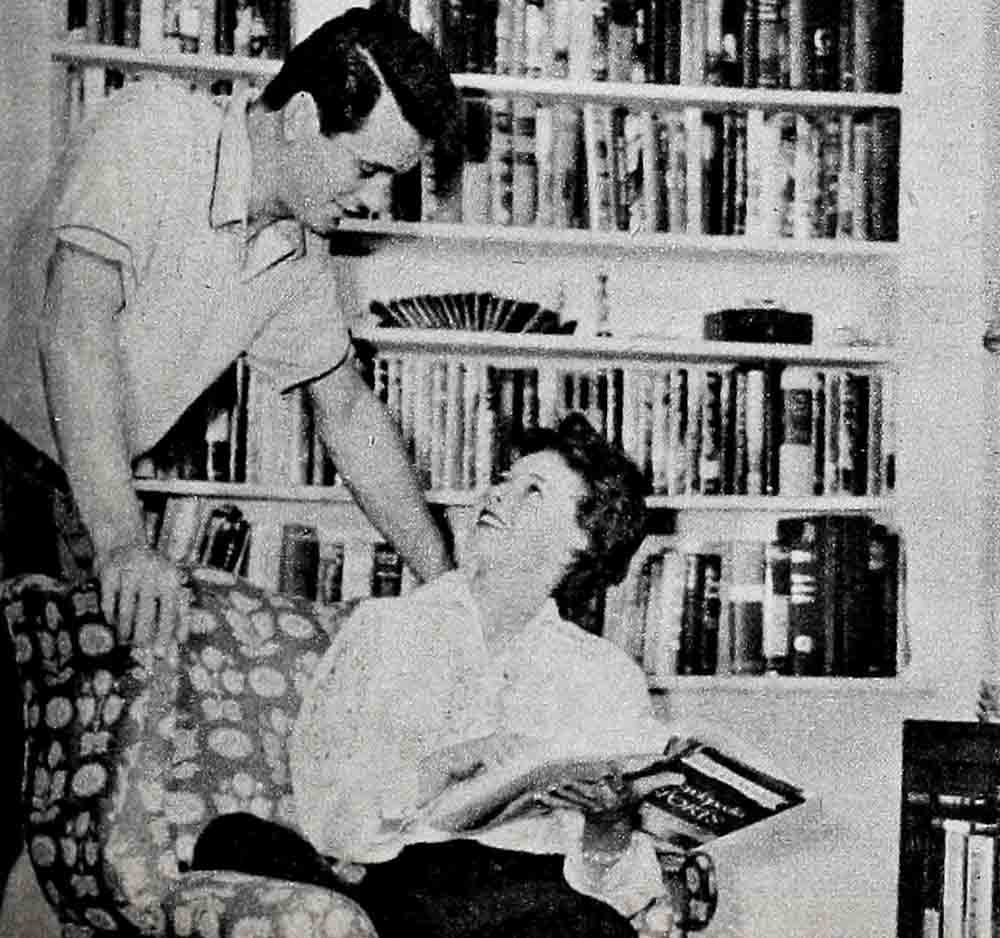

Then, seemingly out of the blue and out of nowhere, came his friendship with lovely and charming Phyllis Gates, who was once the secretary of Rock’s agent, Henry Willson. By that time, however, Phyllis had been promoted to Henry’s Willson’s associate, reading manuscripts and handling promising young writers and talented older ones. For Rock, she was everything he’d ever thought or said he wanted in a wife—quiet, intelligent, with a keen sense of humor and the ability to separate Rock, the movie star, from Rock the serious and shy young man who can stand almost anything but phoniness, or the thought that someone might be cultivating his friendship because it could be advantageous.

Phyllis Gates was without affectation of any sort. She liked serious talk, serious books and serious conversation. Rock knew she wanted nothing from him but his companionship, the fun of being with him. When that fact dawned—really dawned—Rock was lost. From that time on, his second home, his dream house, was on its way. And because our homes always tell—or rather, reveal—so much about us, it was fun to wander through Rock’s abode and guess things about him of which even Rock, perhaps, was not aware.

Rock’s house, naturally, is situated upon high ground. A fellow who has reached up and out for things all his life, who has wanted to have an uninterrupted view of whatever world he found himself in, Rock seems to insist on gaining the same feeling from a house.

Rock is in Warners’ ‘Giant’ and U-I’s “Written on the Wind”

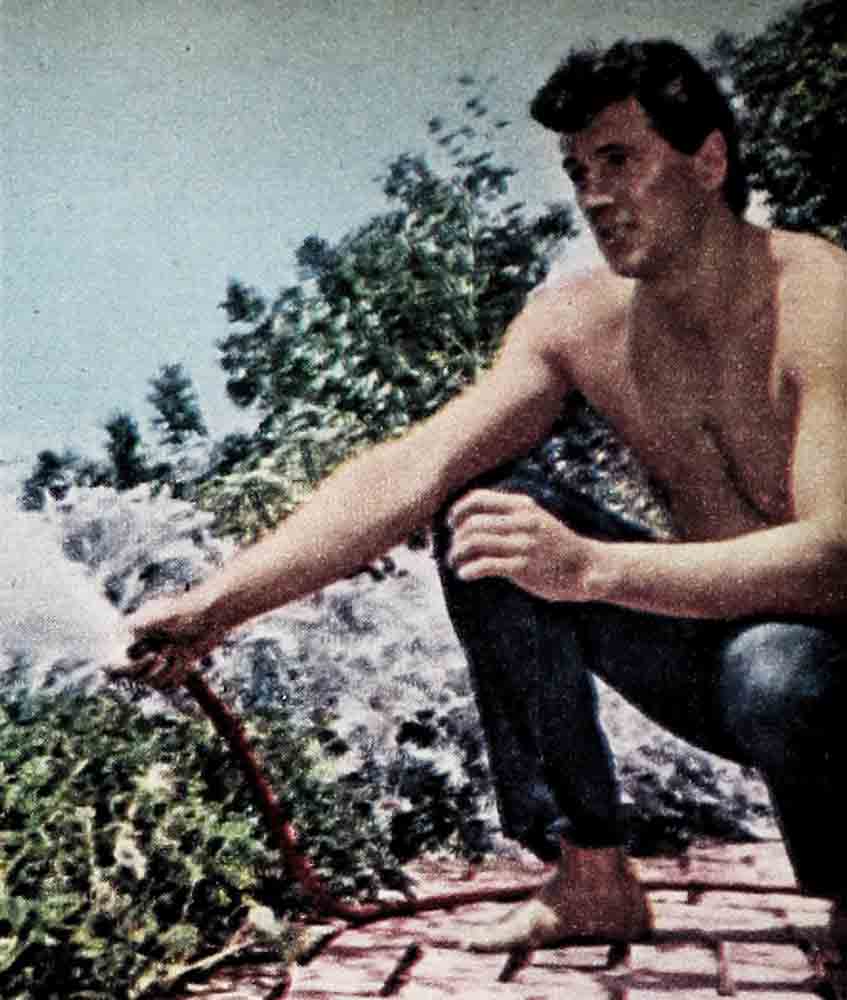

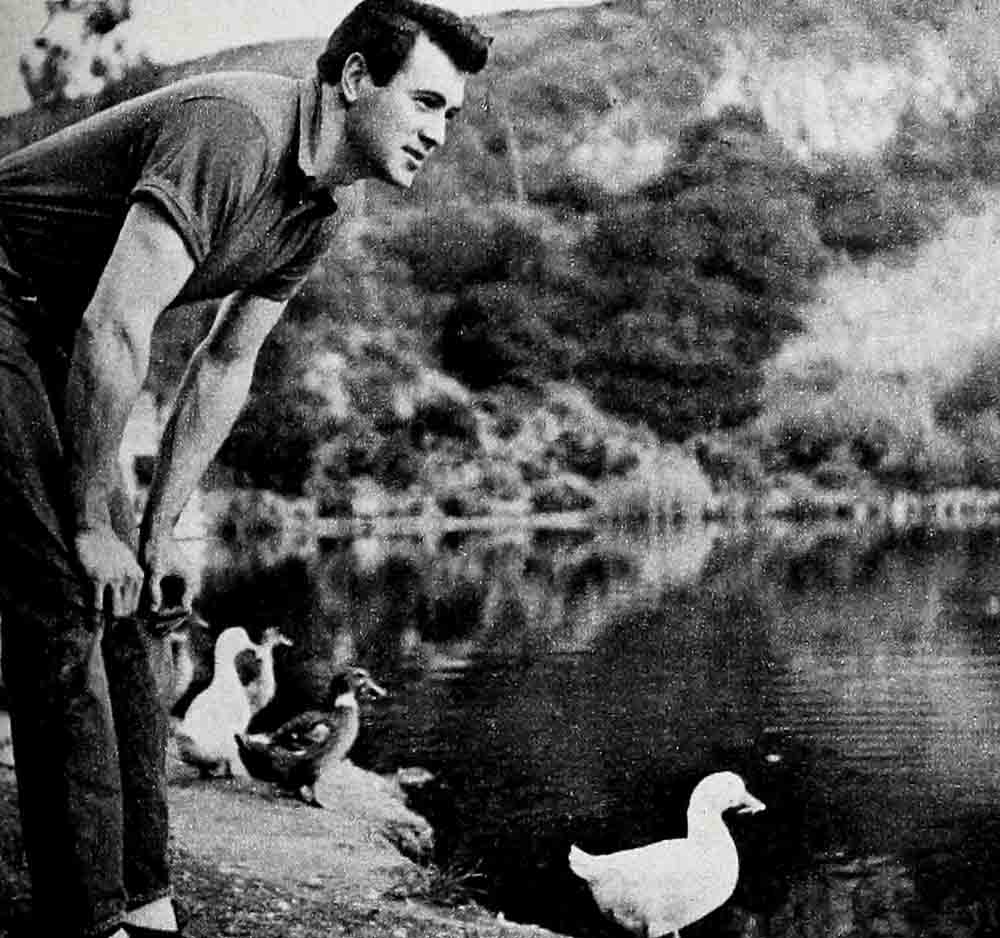

Another Hudson requirement for ideal living seems to be a closeness to nature. Trees, shrubs, bushes, vines, and flowers are native to him, and at least two episodes in his past are directly related to Rock’s love of horticulture.

Rock recalls that one of the happiest periods of his life was the summer of his eleventh year when he was “a very rich man.” He was living with his grandmother, an indulgent woman who considered it normal for a growing lad to roll out of bed at 5:30 each morning, eat everything in sight, and then shag out to the golf course where he-was a caddy. He earned seventy-five cents, plus tips, for eighteen holes, and usually he was able to complete a thirty-six-hole tour before noon. He also earned the reputation as the caddy most likely to retrieve a lost ball in the woods. But he regarded his fame lightly; it was all too easy. After a few weeks, he was as much at home in the thicket as a rabbit in a lettuce patch.

A few years later, Rock’s love for the lofty forest was satisfied by daily summer trips to a spot in Winnetka, Illinois (his home stamping-ground), called Fentress’ Pool, which was located in a ravine off Sheridan Road. The pool was bordered by lilac bushes, weeping willows, wild berry bushes, ferns and lichen. Situated in one of the largest weeping willows was a diving board, completely obscured from below by a phalanx of branches. The result was that a diver, springing off the board toward the shimmering pool below, looked like a slim white bird descending from a passing summer cloud.

Those were the years in which Rock developed his love for nature. And it was inevitable that the house he finally chose to buy was perched high on a Hollywood hill and was surrounded by magnificent oaks and other California trees and shrubs. Rock fell in love with his six-room New England-style farm-house at first sight.

Soon after he moved in, Rock put his green thumb to work and started clearing the courtyard behind the house. It was then he discovered that a mass of vines had overgrown and almost completely hidden a thriving rock garden. So he pruned the vines, thinned the underbrush, and planted petunias and shrubs.

Having temporarily satisfied his garden- ing desires, Rock moved on to other household matters. He made great plans for turning the garage into a playroom and building another garage on the lower level of his lot. Then, in the space now occupied by the driveway, which is a gradually ascending ramp, he planned to have a swimming pool installed.

But, when he outlined this dream to a series of contractors, each di$cu$$ion became more di$couraging than the la$t. Rock finally concluded that he wasn’t paying enough income tax. “If I were paying twice as much tax,” he mused, “I’d be in a bracket in which I could afford a swimming pool, and a pool house, and a system for heating them both.”

While still planning for the pool and rumpus room, Rock moved one of his most precious possessions—his electrified player piano—into the rear storage area of the garage. Eventually, he decided, it would serve as a center for the light- hearted, unpretentious parties he likes so much. The piano had been a twenty- fourth birthday gift to Rock from his parents and a group of studio pals, and it had been the focal point around which Rock’s Avenida del Sol house had been decorated. The word “decorated” is used very loosely in this instance, because the del Sol house was notable for a decor best described as Early Ad Lib with Philodendron Rampant.

Now the player piano is still gathering dust in the back of the garage, serving as an emblem of enjoyment in the past and as a token of a plan for the future. By no means has Rock forsaken his notion of someday being master of a den-rumpus-pool house.

Rock’s idea of the residence superb—as he now eagerly tells his bride, Phyllis—was born during the making of “Captain Lightfoot,” in Ireland. Many of the key events in that picture took place in an old, atmospheric inn. The front door of this inn opened into a huge entry with a beamed ceiling, and the first view of the room revealed a large stone fireplace in an alcove. On both sides of this alcove, were staircases leading to the second story and onto a corridor which looked down on the entry below.

To the right of the entry was a living room with another stone fireplace. This room was carpeted with a flaming-red rug, and most of the furniture was upholstered in vivid Stewart plaids and red leathers. “Big and deep and comfortable with hassocks in front so that a guy could stretch out and take it easy,” is the way comfort-loving Rock describes them.

To the left of the entry was a paneled dining room with a few hunting prints above the plate rail. The furniture was polished cherry, well-aged, and the chairs had down-stuffed cushions.

The kitchen, being a period establishment, had none of today’s efficient equipment, except for a bricked fireplace—which could be transformed into a modern built-in oven and companion barbecue—and a round table and captain’s chairs for stove-side conviviality. But above all, the room had an air of cozy well-being.

“Someday,” Rock promised himself each time he saw the inn, in person or on film, “I’m going to use that plan as a basis for my home. Someday.”

After Rock finished “Captain Lightfoot,” he toured Europe. This experience added new ideas to his mental folio of the future Hudson House. In France and Italy, he visited as many art galleries as possible, picking up a clear-cut “I know what I like, whether it’s Art or not” taste.

“Now I want some oils on my walls,” he told a buddy. “Mainly things that appeal to me, because the landscape brings back experiences that I have enjoyed.”

Later on, while working in “All That Heaven Allows,” Rock added another idea. He attended a Hollywood party one night, gravitated to the den where a rousing bull session was in progress, and caught sight of a four-masted model schooner on the mantel. It reminded him of the first such model he had ever seen in his life: it had been displayed in the mansion which housed the first formal film party Rock had ever attended. He had been very young at the time, unsure and shy, and he had felt like a glob of rosy Jello amid the elegant surroundings and his glamorous fellow guests.

He had spent most of the evening, hands locked behind him, visually examining the majestic model and discussing its characteristics with anyone who joined him at the fireplace. He learned that night how friendly the great can be—and how interested they were in ship models. “Someday,” he promised himself, “I’ll have one, too. There may come a time when I’ll have a guest whose arms have grown too long for his coat, and whose legs have outgrown his trousers, and who needs a topic of conversation.”

Items to be left out of a house often reveal as much about its occupant as desirables to be included. Rock has always said, “There are three things that I’m never going to have in any house of mine: doilies, antimacassars, and heavy draperies with fringe. Never!”

Rock’s dislike for these decorations was developed at an early age. He was only about six when he was taken by his grandmother to visit one of her intimate friends. The hostess was a woman of means and her house reflected the taste of the early 30’s.

There were starched, hand-crocheted doilies everywhere, and all the chairs sported hand-crocheted or hand-embroidered “collar and cuff sets.” The windows wore blinds, casement curtains, and either brocaded satin or double-faced velvet draperies. “When I hid behind them,” Rock recalls, “I could smell the dust.”

He loathed the house. Clocks ticked, boards creaked, musty odors’ wafted throughout as if the air had been disturbed by an invisible passing presence. But Rock had to “be a little gentleman.” He had to “sit still and look at a book.” He had to “let Grandmother visit with her friend.” He was not to ask for something to eat even when he felt his stomach touching his backbone.

One Christmas while his grandmother “visited,” Rock sidled off his chair and slipped into the drawing room to study the tree. There he spied an ornament he had never seen before. It had fallen from a lower branch and was nestled in the cotton batting surrounding the tree. Getting down on his hands and knees, Rock snaked along the floor until he could, he thought, replace the bauble, then return to a vantage point for viewing his good deed. As he tried to back away exactly as he had slid in, a branch snagged him and he tipped over the entire tree with a bauble-shattering crash.

From that day to this, the sight of a doily, an antimacassar, or a heavily- draped window reminds Rock of his gallantry gone awry.

No doilies, antimacassars, or draperies.

All these things taken into consideration, how does the Hudson Honeymoon House stack up in relation to the Ideal?

The best way to answer that is to point out that, for months before they set a date for their marriage, Rock and Phyllis spent every free moment looking for a house to buy, lease, or rent. They wanted one that would ‘include the chief desires of each of them. No luck. With each passing month, Rock’s bachelor quarters began to look better and better.

“We’re going to have to build to get exactly what we want,” Phyllis finally, and wearily, decided.

Thinking of the size of the house they wanted and the possibilities of the future, Rock agreed, adding, “We ought to wait a while. There’s plenty of room for us right now, but. . . .”

The present Hudson Haven covers approximately two thousand feet and is divided up into an entry hall, living room, dining room, a kitchen that—of all the rooms in the house—most nearly seems ideal, two bedrooms and a bath. Outside, the house is flanked by a double garage at one end and a tree-sheltered patio at the other. The living room, though spacious, is cozy and features a beamed ceiling, fireplace and windowed dining alcove. In the kitchen there is a breakfast nook, a barbecue with an electric revolving spit, and, to one side, a walk-in bar with shutters which open out into the living room. The master bedroom has an extra door which leads out to the shaded patio. The other bedroom presently serves as a den.

One of the most impressive pieces of furniture in the house, isn’t in the house —at the present time, that is. Just before Rock started to make “Battle Hymn,” he and his bride decided that the wood throughout the house should be cherry whenever possible. For the bedroom they ordered a double dresser, which was built according to Rock’s specifications and therefore on the massive side.

Once it was installed, Rock and Phyllis stood side by side and studied the result. “I had the impression,” Rock admits, “that the dresser end of the room was slowly sinking into the hillside.”

“It’s too large for the room, isn’t it?” Phyllis said sadly.

So, the following Sunday, Rock and a friend covered the dresser with craft paper and moved it into the garage.

However, the cherry wood hi-fi cabinet in the entryway proved to be perfect, as did the lamp tables on which Phyllis put the whisky-keg lamps Rock had brought home from England.

On the wall between the wide windows that overlook the Hudsons’ private forest, Rock hung one of the three oil paintings of Venetian scenes that he and Phyllis spied in Mexico City while on their honeymoon. “Venice is one of the places I’m going to take you to some time soon,” Rock had said.

“We’d better have the scene to remind you regularly,” said his wife with a grin.

The second painting has been hung in the entryway, and the third in the den.

The carpeting throughout the Hudson house is bisque-colored, the living-room walls are cream, the bedroom walls are pale turquoise. The living-room sofa is done in an off-white fabric of an interesting texture, and the accent colors are creamy turquoise and mint, picked up in a huge hassock placed beside the fireplace, in throw cushions on the sofa, and in the plaid-covered fireside chair.

All the windows are obscured by mov- able shutters, a concession to Rock’s dislike for flouncy window treatment that hasn’t been entirely successful. “Too much bother to open, close and fiddle with until you get the right amount of light,” he laments. “There must be some other answer.”

Aside from the fact that the only fireplace in the house is brick and that there is no swimming pool outside, Rock discovered another serious lack: no glass shelves whatsoever had been installed for a lady’s perfume collection. “It took a week to put up enough shelves for Phyllis,” is Rock’s way of kidding his wife.

“Who gave me most of the collection?” is Phyllis’ retort. “Besides, who has taken up all our drawer space with the stock of gloves he brought back from Italy?”

“We need more storage space, that’s for sure,” Rock concedes. “And a big den with a model ship on the mantel, and a huge bedroom to accommodate that double dresser, and . . .”

Naturally, the Hudsons will have to build. And you can be sure their future love nest will be high on a hilltop, close to the stars, where they will be able to put down roots in the ground while keeping their dreams in the clouds.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956