What It’s Like To Be Tony Curtis’s Wife

Lots of times when I’ve been on tour and talked with strangers they’ve asked me what it’s like to be Tony’s wife. It may be because they’ve caught his humor on the screen, or because they’ve read zany stories about his clowning. Whatever the reason, most people who’ve never met Tony seem to think life with him is a marathon comedy.

It’s that all right, but it’s a lot more. They say a woman can be married to a man for fifty years and still discover new things about him. It’s certainly that way with me. In the two years we’ve been married I’ve continued to learn new things about Tony, and each discovery seems more important than the last. His sensitivity, his aggressiveness, his pride and his humility, his boyish ways and his maturity—all of them keep cropping up. And I don’t suppose anything will ever affect me as much as his gentleness when I lost our baby last July.

Most people have to know him a while before they realize that Tony runs pretty deep. He is a truly funny guy, and the humor of our life together is a great blessing, yet it wasn’t his humor that I noticed first.

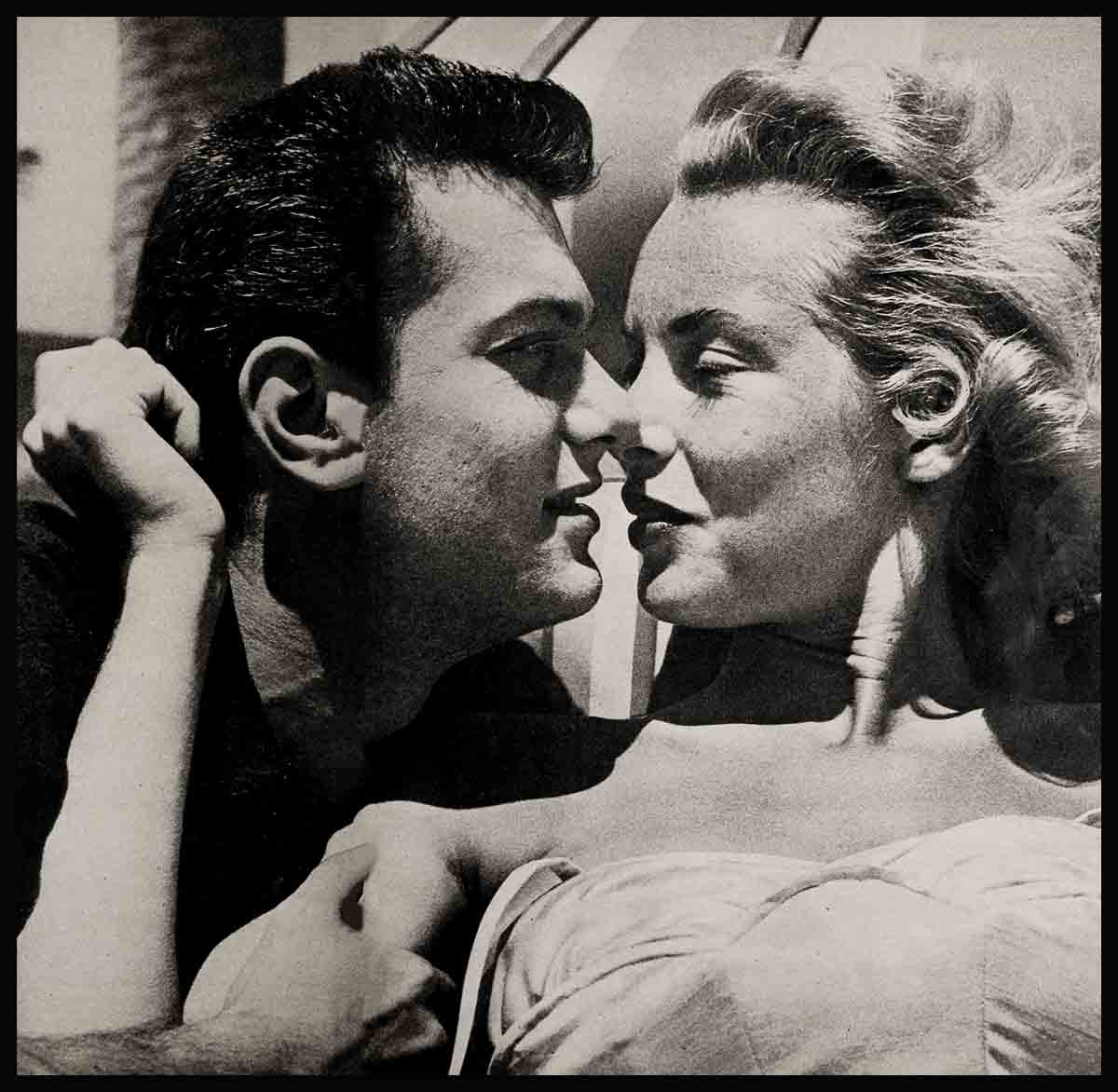

When I met him at a Hollywood party I noticed, as any girl would, that he was very attractive.

He seemed quiet, and I was impressed by the fact that he had none of the brash quality that so often surrounds successful young men. At that time he wasn’t what the town would call successful—he hadn’t yet had a leading role in a picture—but his fan mail was coming in by the truckload and he must have realized he was definitely on his way up. He didn’t throw the promise of his future at anyone; rather he seemed to efface himself and let others have the spotlight.

I saw him again some weeks later when we both joined a group that met once a week to study dramatics at the Actor’s Lab. Most of the kids looked on it as a social gathering, but Tony was deadly serious about it. He seemed so shy in person, yet in his work he had no inhibitions. If he was asked to do pantomime, to ‘be’ Notre Dame or July’s last snapdragon, he threw his heart and soul into it. I remember the first skit we did together. We were supposed to be parents watching our child at his first piano recital, and while we were to be bursting with pride at first, we were to realize slowly that the rest of the audience wasn’t nearly as appreciative. When Tony turned to look at me toward the end of the skit there was such torture in his eyes, such real emotion, that I still remember the jolt it gave me. I told myself that this Tony Curtis was not only deeply serious about his work, he had great sensitivity.

These were impressions gained only in passing. I didn’t begin to know Tony until we dated, and in that I found something else to admire. He had seen me only when I was with Arthur Loew, and it wasn’t until the group at the Actor’s Lab dissolved and then reconvened to plan for a new class that Tony saw me with another escort. He asked me then if I was going steady with anyone and as soon as I told him no, he asked for my phone number. He called two days later to ask for a date, and I realized that he may have wanted to phone me before, but observed a gentleman’s code in not trespassing on someone else’s territory. I liked him for it, and I liked him because he didn’t rush impetuously into a frantic courtship. Instead of trying to date me every night in the week, he showed solid sense by asking to see me once or twice a week. I didn’t have to worry, with Tony, about getting home early when I had a morning call at the studio the next day. He understood without my having to ask him, and always took me home at a decent hour.

We talked a lot on those first dates. It didn’t seem to matter where we went. There was no need for entertainment because we had so much to tell each other. I’d seen flashes of his humor before—Tony can never be serious for too long—but the ice really broke the night he handed me a pair of silver earrings I’d never seen before. “This is great,” I said. “They’re not mine. You’ve forgotten which girl they belong to.”

At that he broke up and howled. He’d bought them for me as a gift, of course, and I guess that was the beginning of our schtickloks, our word for the crazy routines we sail into every once in a while.

Even so, I think he was more serious when with me than with anyone else. I got the impression that Tony wasn’t very sure of me. I even felt he wasn’t too used to dating girls. It made sense that he wouldn’t be. His gang in New York weren’t the type to turn romantic very early in life, and besides, I had the feeling that because he was so good looking he’d been the subject of a handful of crushes back in the Bronx. Travelling with the gang as he did, he couldn’t very well break off and turn Casanova. They wouldn’t have liked him for it, I suppose.

His manners were perfect, mainly because they stemmed from his thoughtfulness, but he just didn’t seem at ease with me. I remember on our second date he spilled a glass of water on my dress and I’ve never seen anybody so embarrassed or upset. On the day he started his first leading role in The Prince Who Was A Thief,I sent him some champagne, and he was so appreciative you’d have thought I’d sent over a Brink truck loaded with a million dollars. Tony wasn’t a smoothie; he wasn’t a wolf; he wasn’t a Beau Brummel. He was just an average boy with qualities that made me like him more and more.

Along with his uneasiness with girls went a strange distrust of them. I’ve never known why, but it was as if Tony expected me to be dishonest with him. As a result, every time he found I’d told him the truth, he was as happy as a puppy with a bone. He has told me since our marriage that when he asked for a date and was told I had an engagement that evening, he used to wait down the street to find out if this was the truth. And when he’d see me leave the house on another man’s arm, he was almost as pleased as though he’d been with me himself.

I don’t know why, but it seems I frightened him. I went to New York soon after we began dating, and before I left he said he was sure he’d never see me again. I told him quite frankly that I was going for a rest, that I had friends there and that I would probably go out with one man in particular. He took me to the airport, still believing this was the end of our friendship and that for some reason I was too weak to tell him. He stewed for days afterwards, all during the shooting of his picture. The cast and crew kept telling him to telephone me. “I can’t,” he said. “She’d hang up on me.” But he did call, and was amazed when I talked to him. He was even more surprised when I wired I was coming home and asked him to meet me at the airport.

Perhaps this idea of his had some connection with the way he presented me to his friends. Tony’s friends are of all ages and interests—a wider variety I’ve never known. He gradually introduced me to all of them, standing on the sidelines and watching to see my reaction. It was as if he expected me to suddenly turn bored or impolite, as if he’d found a golden egg and wanted to make sure it wasn’t all a dream. I realize now that he was desperately anxious for them to like me as much as he did. Tony has a tremendous loyalty to all his friends, a love so deep that he feels the compulsion to share his every joy with them. He calls them all frequently. He must know where they are at all times. It is almost an obsession with him.

I have thought that this might be the result of his brother’s death, years ago, in New York traffic. Tony lost track of Julius and it was the last he ever saw of him. The tragedy was such a shock to Tony’s emotional heart that it is perhaps the reason that even today, he must know where and how his friends are. And perhaps it was the reason he felt he was losing me when I went to New York.

We hadn’t dated very often before the evening we were driving along and he suddenly said, “Jerry’s home. Let’s call him.” Tony had told me a lot about Jerry Lewis and their friendship, and while I had felt some trepidation about winning the approval of others, the prospect of meeting Jerry loomed like an impossible task. I’m not the quick-answer type, and having seen Jerry only as an entertainer, I had a sinking feeling that Tony’s best friend would think I was as interesting as a squeezed lemon. Jerry and Patti had been away on tour ever since I’d Known Tony. It was typical that Tony should suddenly know they had returned. It wasn’t the last time I was to experience his uncanny sixth sense.

We telephoned and sure enough, they were home and wanted us to come over. I kept telling myself I couldn’t change, that if they didn’t like me the way I was, I couldn’t do much about it. The minute we walked in, Tony and Jerry went into a loony routine. It was the first time I’d seen this craziness of Tony’s, the wacky routines that people now seem to think monopolize his days—and I loved it. Patti and I went off in a corner and talked girl-talk, and I realized, with considerable relief, that I wasn’t expected to “be on” when I was around Jerry. I could tell Tony was as happy as a clam that evening, so I knew that I had been accepted into the family. Then Patti and Jerry included me in one of their home movies. You can’t get closer than that to the Lewis clan.

By now I was growing more and more certain that Tony was a thoughtful, goodhearted, sensible boy, and the visit to his parents boosted him another notch in my estimation. Mom and Pop Schwartz are the salt of the earth, and truer gentlefolk than many millionaires. I say this because they lived in a tiny, unpretentious house in the valley, and although they were poor in material things, they were richer in love than any people I have known. Tony told me before we went to expect his mother to be excited. She had seen me in a movie and was flustered as a hen at the thought of having me to dinner. She couldn’t know that I was even more flustered than she, because I wanted Tony’s parents to like me. I wanted very much to have them like me.

It was one of the easiest, happiest evenings I ever spent. We played games with Tony’s kid brother, Bobby, and I noticed Tony’s understanding and patience with the child. We ate dinner in the kitchen, as I used to do at home, as most people do, and I liked it because Mrs. Schwartz made no apologies. I ate everything on my plate and a big helping of dessert, loving the Hungarian cooking. Mom Schwartz beamed at me as though I’d given her a mink coat. Afterward, I helped her with the dishes, and Tony and Pop sat back in the living room, watching us like proud roosters. The Schwartzes gave themselves to me as they were, and I loved them for it. And that night I saw Tony’s devotion to his family. A strong, unbreakable link in his life, a thing I like in a man.

After I came back from New York we limited our dates to each other. That was a period of getting to know each other well because marriage was in the back of both our minds. We talked about our childhood, our families, our careers, our beliefs, our philosophies. We were pretty well talked out when Tony left on a trip to Denver for MODERN SCREEN and I took off for Pittsburgh to make Angels In The Outfield. He telephoned me constantly and one night when he couldn’t reach me, he was frantic. I still didn’t know, then, about. Tony’s obsession; his having to know where his loved ones are. If I had, I most certainly would never have let it happen. It was the night when the cast of the picture and the Pirate team had a wingding, one of those social things that go with picture making, and I didn’t get back to my hotel until three A.M. Tony had been calling all evening and when he finally reached me, soon after my return, he was almost hysterical with worry. I wanted to beat myself for having put him through such a wringer.

It was that night that he asked me to marry him, and when I cautioned that he was upset and we should talk it over later under more normal circumstances, he thought it was my way of refusing him. By the time he met me in Pittsburgh he had simmered down and regained his confidence sufficiently to bring me a gold ring, set with a pearl. It was a beautiful thing, and the first opportunity I had for knowing that Tony’s taste in such delicate things is exquisite. Despite the ring, I kept insisting that we talk things over when we got home. I already knew what I wanted, but I wanted him to be absolutely sure. As I look back now, I don’t know what more assurance I could have wanted. Tony is impulsive in small matters, but in the big things, the things that count, he’s cautious as a cat. Jerry and Dean settled it for us when we stopped to see their act in Chicago on our way back to the coast. We sat in the back room thinking we hadn’t been spotted, and then we saw a table moving over the heads of the customers. The waiter put it down in the middle of the dance floor and then Jerry began yelling for us to come up and make ourselves at home. He saw the ring right away and before we could stop him, announced gleefully to the whole house that “we were going to be married. I don’t think Tony really wanted to stop him—he wanted the whole world to share his happiness.

I saw Tony’s strength when he stood up to his studio. They didn’t want him to marry so soon, but Tony said, “If my popularity is only because I’m single, I might as well give up acting right now.” Their disagreement upset me, but Tony made sense, and so we were married—in Greenwich, Connecticut.

I left shortly after to come back to Hollywood to make a picture, and that brief separation affected him so much that he actually got sick, and the studio allowed him to come home for a brief week-end. I began to understand how violently emotional Tony is, how he gives himself so completely: to those he loves.

Then his father had the heart attack and again I saw Tony’s strength. He telephoned the doctor and the hospital, long distance, made all the arrangements, canceled his tour and flew home to his dad. He spent all day every day at the hospital and I joined him there after work every day. We stayed until 9 P.M. and then ate dinner on the way home. In his devotion he forgot himself completely, and I worried that he might collapse. I remember the day he came to the set where I was shooting. He looked terribly haggard and he came to me in my dressing room and put his arms around me. I knew then that he had done with being strong, that he needed my help, and much as I had admired his strength, I loved him more that day for showing human weakness.

All of this happened in the first month of our marriage, and I think in that period we lived a lifetime. The stress and strain it put on our marriage, which at that time should have been a carefree honeymoon, gave it the most solid foundation possible. If you can go on loving and understanding through adversity, you build something wonderful with each other.

I learned about his generosity. With Tony, what’s his is everyone’s. Jerry Gershwin came over one day while Tony was shaving and admired his razor. “Here,” said Tony, “take it.” He is possessive only where people are concerned, and he finds it hard to let them go. If a friend disappoints him in some way, Tony tries to find out why it happened. If there is no reason for a friend’s misusing him, that person no longer has Tony for a friend. But Tony suffers real torture in the process of disillusionment. He is gradually learning that open trust can be betrayed, yet every time it happens, he is deeply hurt again.

I learned that he dislikes arguments and hates to fight. In our marriage he can’t stand loose threads of misunderstanding, and has proved time and again his willingness to try to work things out for the better. He has pride and humility, and is never too stuffy to say, “I’m sorry.” We are really 50-50 on that score.

I learned about his moods. Sophie Rosenstein, who was dramatic coach at Universal-International before her death, once asked Tony if I had ever seen him when he was “in one of his moods.” He told me about her question, and I laughed and said he couldn’t scare me. After our marriage, I knew what Sophie had meant, Once in a while Tony became very withdrawn, and when I questioned him about it, refused to talk. “Look,” I said. “If you’re enjoying a mood I don’t want to break into it, but in the interim I’m blaming myself for your unhappiness. I wonder if I’ve done anything wrong, if it is my fault.” Gradually he began telling me, and I came to know that many times he was upset by little things; something that had gone wrong on his picture, or something he had read, and he hadn’t wanted to tell me because he was afraid I would think he was silly to be affected by such minor things. “I get upset about silly and sentimental things, too,” I told him. “Don’t mind me.” So he learned to talk things out with me and his moods don’t come so often.

Last June he went into another one, and it took me four days to find out he was. worried about going to Honolulu to make Beachhead, Tony has always had a fear of flying. I don’t know why—he hadn’t seemed to be bothered by long days in a submerged submarine during the war, which to me would be much more frightening—but he is terrified by planes. So are

a lot of other people, but he is still ashamed of the fear. The studio wanted him to fly to Hawaii with the company, and he wanted to take the boat. But the boat would mean a longer separation for us. He made himself miserable over it until I found I could go with him by boat. I’d be on 24-hour call, but I could go. As it turned out, we had the trip over as well as six long days together, the only real vacation we’ve had together in two years of marriage.

I stayed until he began work, and when I got home I learned we were going to have a baby. I don’t know that there was ever a man as excited as Tony. He was delirious with joy. We had decided to limit ourselves to a phone call every other day, but when I phoned Tony the news the budget broke wide open. He hates writing letters, but he wrote me every single night we were apart. I will always treasure the letters about the baby. He wrote that he was reading serious books in every spare moment, books about the earth and religion and life itself to help him to understand our own miracle.

And then when I lost the baby, we had again that round robin of strength and dependence. He had called me on Saturday, when I was feeling a bit rocky, and although I said nothing about it he detected something in my voice. He called back later that night. “I can’t go to sleep. I know something’s wrong. What is it?” He called again on Monday, my birthday, and I assured him everything was all right. I lost the baby Tuesday evening, and although it wasn’t his night to phone, he knew something was wrong and put through a call. That deep bond again, the closeness he feels with those he loves. He called at home and got no answer and then called his parents. My own folks had told the Schwartzes that the doctor had given me a sedative and put me to bed, and when Mom told Tony that, he knew. He wrote me that night and called at the hospital the next morning, and afterward, once he knew I was all right, he wrote the most beautiful letter Ive ever read. It was gentle and loving, yet strong. He was doing his best to bolster my spirits, from 3000 miles away. The letter was so like Tony, so tender, and yet not without humor. In it he wrote, “We will have forgotten all this in the years to come when we’re surrounded by our four children, not to mention the twins at college, and George. George? Who’s George?”

I couldn’t help laughing, and in the days that followed, his letters and phone calls gave me the strength I needed. Then, imperceptibly, I began feeling a resentment. I was sorry for myself. There I was, enduring our tragedy all alone, and Tony was far away, laughing and talking with other people. He seemed to me to be untouched by it and I was sure he couldn’t feel as stricken as I did. And then on Sunday he called, and I could hear the tears in his voice. He was no longer the pillar of strength, the comforter. “I can’t stand it any longer,” he said. “I’ve got to come home to you.”

That snapped me right out of my orgy of self-pity, and I began to bolster him. It’s like that all the time. One of us leaning on the other.

Tony is insecure in some ways, but he has a great, strength, a strong self-will. He is not afraid to make a decision, nor to act. We need each other, but I know that in a pinch, he is the stronger one of us. The long separation: while he was in Hawaii was difficult to bear, particularly under the early circumstances, but it taught us even more what our relationship means to each of us. I think we both grew up a lot during those long weeks, and with time and space to view ourselves, felt happier than ever in our marriage.

People have asked me, when Tony is working in Hollywood and calls me ten times a day from his set, “What’s the matter?—Doesn’t he trust you?” But I know what it is. It’s because he’s Tony, and he must know that I am here and well, that his world is still safe and happy. I like it this way, this being loved so much and needed so much. That’s what it’s like to be Tony’s wife.

THE END

—BY JANET LEIGH

(Tony Curtis can now be seen in Universal’s All-American.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953

No Comments