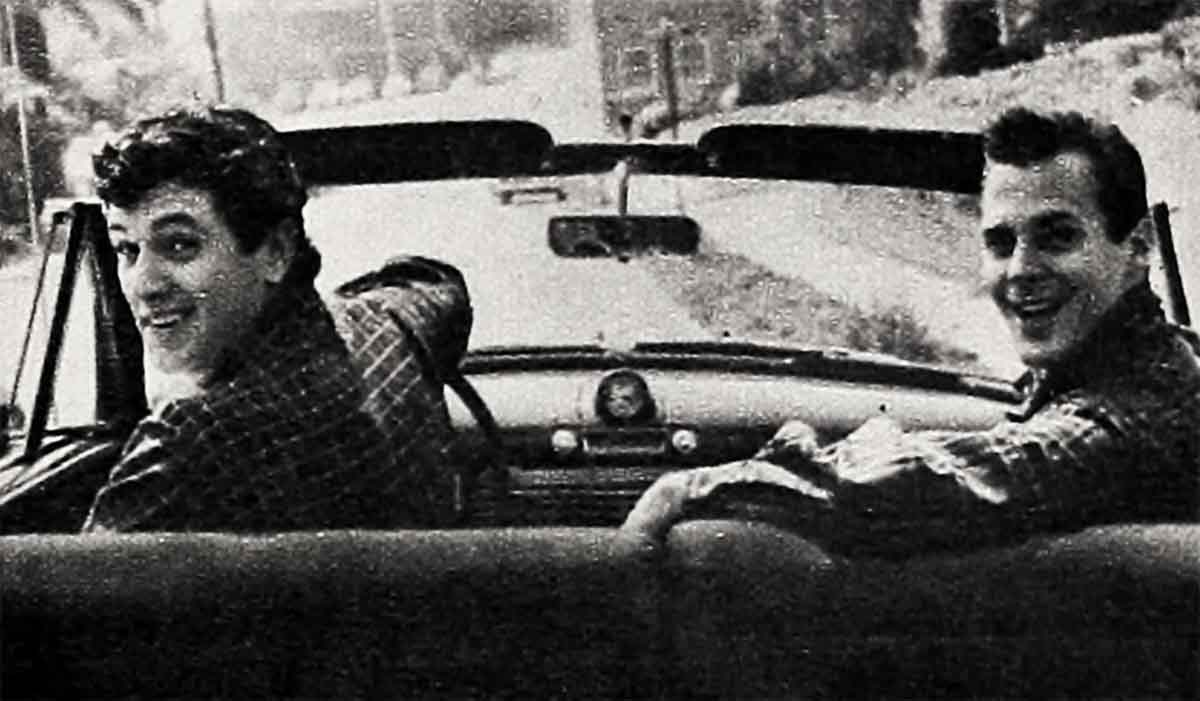

Bachelor’s Bedlam!—Rock Hudson

A guy named Rock Hudson and I have insanity in common. That’s probably why we’ve managed to live together for more than two years. I first met Rock soon after I’d come to California to find out about my chances in movies. I’d just signed with Rock’s agent, who gave a party and invited all his hopefuls. When I walked into the room there was a big guy pounding on the piano, fracturing some tune that I couldn’t recognize. That in itself should have warned me, but I thought anybody who had the nerve to murder a melody like that must be interesting, to say the least.

At that time Rock was living alone in a house in the Hollywood hills, and he wasn’t liking it. Rock has to have somebody around all the time because he talks a great deal, and when there’s no one there to answer he starts thinking about seeing a psychiatrist. I was at loose ends myself, and when we found we hit it off so well, we moved into a house out in the valley. Just recently we moved back into the Hollywood hills. But wherever we’ve shared the rent, it’s resulted in typical bachelor’s bedlam. Rock leaves his bath towel over the top of the door, or flung into the tub, or sometimes on the floor in a pattern of studied confusion. Whenever I trip over one I make a suggestion between gritted teeth that he try hanging it on the towel rack. Whereupon he reminds me that I don’t even leave my towel in the bathroom—I drag it into my bedroom and leave it to soak the bedspread.

When I came to California, leaving behind a few years of study about Business Administration at the University of Maine and Carnegie Tech, I had pre-conceived ideas about the way movie people live. I thought it was a perpetual round of parties at swank places like Ciro’s. It’s been a welcome surprise to find that Hollywood actors like the simple things in life. At least, Rock does. If it happens that neither of us has a date for an evening (a rare occurrence), we hop in his Oldsmobile or my Ford and go bowling or play pool, or even spend an hour in a penny arcade. Sometimes well haunt Army-and-Navy stores or second-hand joints. These are the times we always come home loaded with stuff we can’t possibly use—anything from a diver’s helmet to an old carriage lamp.

There isn’t any of the much touted glamour in these kind of pleasures, but then Rock is a small town boy. He grew up on the wrong side of the tracks in Winnetka, a pleasant village north of Chicago where most of the residents retain butlers as a matter of course. His father was a garage mechanic who tended to spoil his only offspring, but his mother kept a pretty stiff hand on the reins—or at least she thought she did. Rock figures he could get around the maternal discipline pretty well by the time he hit his teens.

Eventually Rock found his way, completely unconsciously, into the upper circles of Winnetka society. It wasn’t that he was a junior social climber; it just happened. It started through a coincidence, and I found out about it the night he ordered a broiled lobster and took the thing apart with the deftness of a member of the Four Hundred. Rock had always talked about his childhood as a time of comparative poverty, had belittled his education, and I knew the family table had never sported delicacies or formal settings. Consequently I was curious.

“How do you know how to attack a lobster?” I said.

And he told me about some rich kid—I forget his. name—call him Tommy. Tommy was a sissy kind of a youngster and the town bullies were always on the lookout for him. One day Rock saw Tommy being beaten unmercifully by one of the tougher boys, and when Rock pulled him off, the bully wanted to fight him. He got his wish, and limped home wishing he hadn’t. Several days later Tommy’s mother called Rock’s mother, told her about it, thanked her, and asked if Rock could come to dinner. Rock didn’t realize it then, but Tommy’s mother had the idea that if Rock would teach her son how to use his fists, she in turn would teach Rock the manners of the upper crust. Rock took over with Tommy, and by the time he’d toughened up the kid they were close friends. It went on from there. Rock always had jobs after school and in the summer—carrying, putting up awnings and taking down storm windows, driving a truck, all that sort of thing—and nevertheless was welcomed as a member of Winnetka’s inner circle.

I became interested in dramatics through a professor at college, but Rock decided to be an actor when he was ten years old and saw a movie scene where Jon Hall dived from a crow’s nest into a shimmering lagoon.

He went in for plays when he got to high school and finally came to California to see if anybody could use him for jumping out of a crow’s nest. They’ve used him for that and more. He’s been a pilot, a cowboy, a boxer and a soldier, and most recently a lace-cuffed dandy in “Scarlet Angel.”

His work requires that he get up at what he considers an unholy hour, and in order to accomplish this we have gone through a lot of turmoil. I say “we because I’m involved, too, when an alarm clock goes off inside an inverted dishpan. At first he tried an old-fashioned, garden variety type of alarm clock. Even in my own room down the hall, this particular instrument awakened me immediately, but it didn’t rouse Rock. Then he bought a contraption that sounded as if Big Ben had moved into bed with him. That didn’t work either. So he put Big Ben under the aforesaid dishpan, and when that went off it used to raise me right out of bed and smack me to the ceiling. But Hudson slumbered on. He finally resolved to employ a message service to call him every morning, because the staccato ring of a telephone will waken him.

He consequently loathes the ring of phone at any hour—considers it an invasion of his privacy. And when my girl friends call at odd hours he gripes about it for ten minutes after they’ve hung up.

As a matter of fact, he gets angry when his girl friends call, ay least if he’s asleep at the time. On the other hand, part of his reaction is due to the fact that he dislikes possessiveness in women, and usually when a girl calls she wants to know what you’re doing and why, or where you’re going and where you’ve been. Rock likes his freedom and when he gets married some day he’ll probably be surprised to find that Mrs. Hudson wants to know where he’s been and where he’s going. It’s a feminine type of attack against which at least two males put up a roaring defense.

Our tastes in girls differ, another factor that allows us to live together in peace. We often have respect for the same girl but we’re never attracted to the same types. Rock never cared particularly about looks. The girls he wanted to marry before he was sixteen were all ugly as mud fences, according to him, and he only liked them because they could run fast or had a good eye with a sling shot. But he’s undoubtedly changed his mind, what with the selection in Hollywood. At least he’s run the gamut out here. He has dated Vera-Ellen and Marilyn Maxwell, Barbara Lawrence and Joyce Holden, Ann Blyth and Piper Laurie, to mention a few. All this dating is only natural—a guy’s not going to curl up evenings with “War and Peace”—not when he lives in this town.

My own dates are generally girls who aren’t in the picture business. Nevertheless, I usually get home later than Rock. There’s a reason for this. When I get home I haven’t eyes for anything but bed. But when he gets home, even if dawn’s about to break, Rock wants to talk. If come in early it’s a cinch that he’ll stomp around when he arrives a few hours later. He can’t stand seeing anybody else sleep. When he was in the Navy and had to stand watch in the middle of the nigh is drove him crazy to see all the other guy snoozing. So when I’m in the Land of Nod he stomps and crashes around until he’s sure I’m awake. Then he starts talking. And there I am, a dead duck for the night.

Another time he’s sure to begin talking is whenever I read a book. I sit down, I pick up the book, and I open it. “Hey,” says Hudson. “Look what’s playing down at Venice! An old Lana Turner movie!”

We’re both batty about Lana, and will go miles to see one of her pictures. I go to premieres just in the hope I’ll see her. I see everybody except Lana. Rock and I have gone to Palm Springs because she was there, and found she left just before we arrived. He got to meet her one day, on a set down at M-G-M and he wed up at home that night with an idiotic expression on his face. All he’d tell me, much as I plied him with questions, was that she has a firm handshake and that she said, “I’m glad to meet you, Mr. Hudson.” This guy has all the luck.

Rock’s a lot farther along in picture work than I am—my one and only stint has been a role in “What Price Glory” at Twentieth—and though he probably could help me, we have a sort of unwritten law that he won’t. He’s had me over to the studio for lunch, and he invited me to the set when we first met so that I could see how movies are made, but we agree that he’s not to throw my name around when there’s a role open somewhere. I don’t want him to feel he has to lend a hand. We figure it’s better this way.

I usually go with him to see his own pictures, and am lucky if I leave the theater without a compound fracture. Hudson squirms and fidgets and shrivels in his seat. This is a disease common to actors who are watching themselves on the screen. He decides this scene was awful or he could have done that scene much better. He always wants my opinion, and I give it to him straight, whether it’s good or bad. But no matter how rough I am, Rock is his own severest critic.

Rock’s good nature is his first attraction for people, I think. They conclude that he’s a big overgrown kid who doesn’t require much probing. I know better. Actually he’s a pretty complex guy, but he doesn’t let people know it unless they’re close to him. He is moody at times, usually when he’s depressed about his work. And he has a temper that simmers for weeks, then comes to a boil and finally explodes. But it’s over in a hurry. He picks up something, anything, and throws it, and a minute later he’s putting a record on the phonograph.

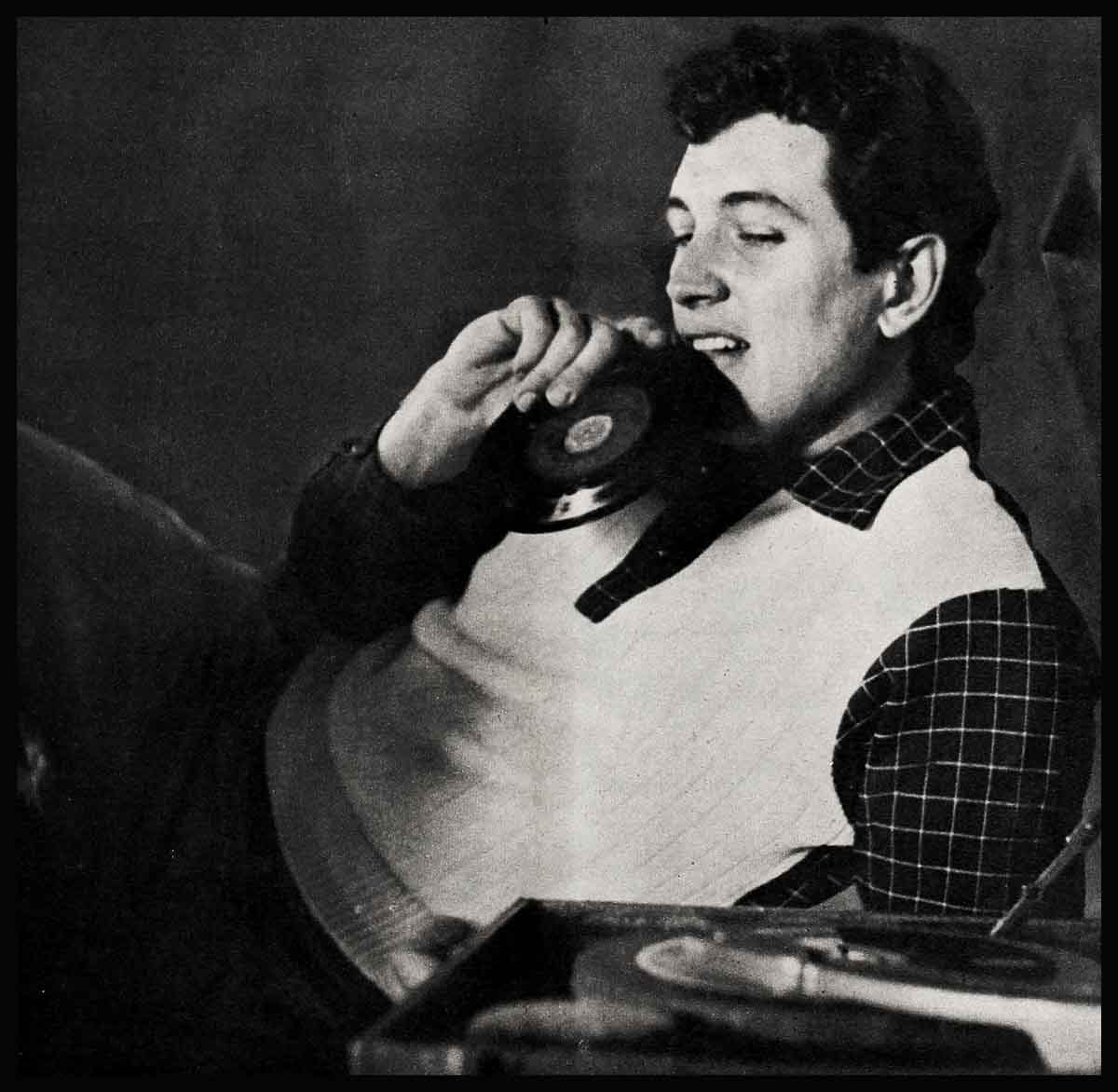

Our taste in music was poles apart when we first met. I grew up with classical stuff, and never appreciated folk tunes or western ballads until Rock and I merged our record collections. Now he’ll pick up a Brahms album, listen to it for a while and then interrupt my siege with the newspaper. “Hey,” he says, “this Brahms boy was all right!”

He’s a pretty easy guy to live with, and other than the yak-yak routine, I have only one complaint. His procrastination is giving me ulcers. Rock never gets ready until the last minute. He’s supposed to pick up Marilyn in fifteen minutes and he’s still sitting around in blue jeans, talking about his grandmother or his dog.

“You’ve only got fifteen minutes to get over there,” I announce.

“Thank you very much,” he says. “Now, as I was saying . . .”

But he always makes it. When we’ve planned to play tennis he can never find his racquet at the last minute, yet we’re always at the courts on time. We like the same sports, and can give each other a decent game in almost anything. There’s only one sport in which I refuse to join,

and that’s water skiing. It’s the love of Rock’s life, but I’ve heard him talk about it and somehow I don’t want to be around when he gets on skis. We play golf often, sometimes with my brother and parents out in Pasadena. Coincidentally, they are good friends of Rock’s mother and stepfather, who live only a few blocks away. My parents have sort of adopted Rock as a member of the Preble clan, and are of the opinion that I couldn’t live with a nicer guy. They may be right. After being around him for a couple of years, I’d be bored to death if I were involved with Business Administration back East.

THE END

—BY BOB PREBLE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952