Jimmy, My Wedding Ring Is Gone!—Jimmy and Evy Darren

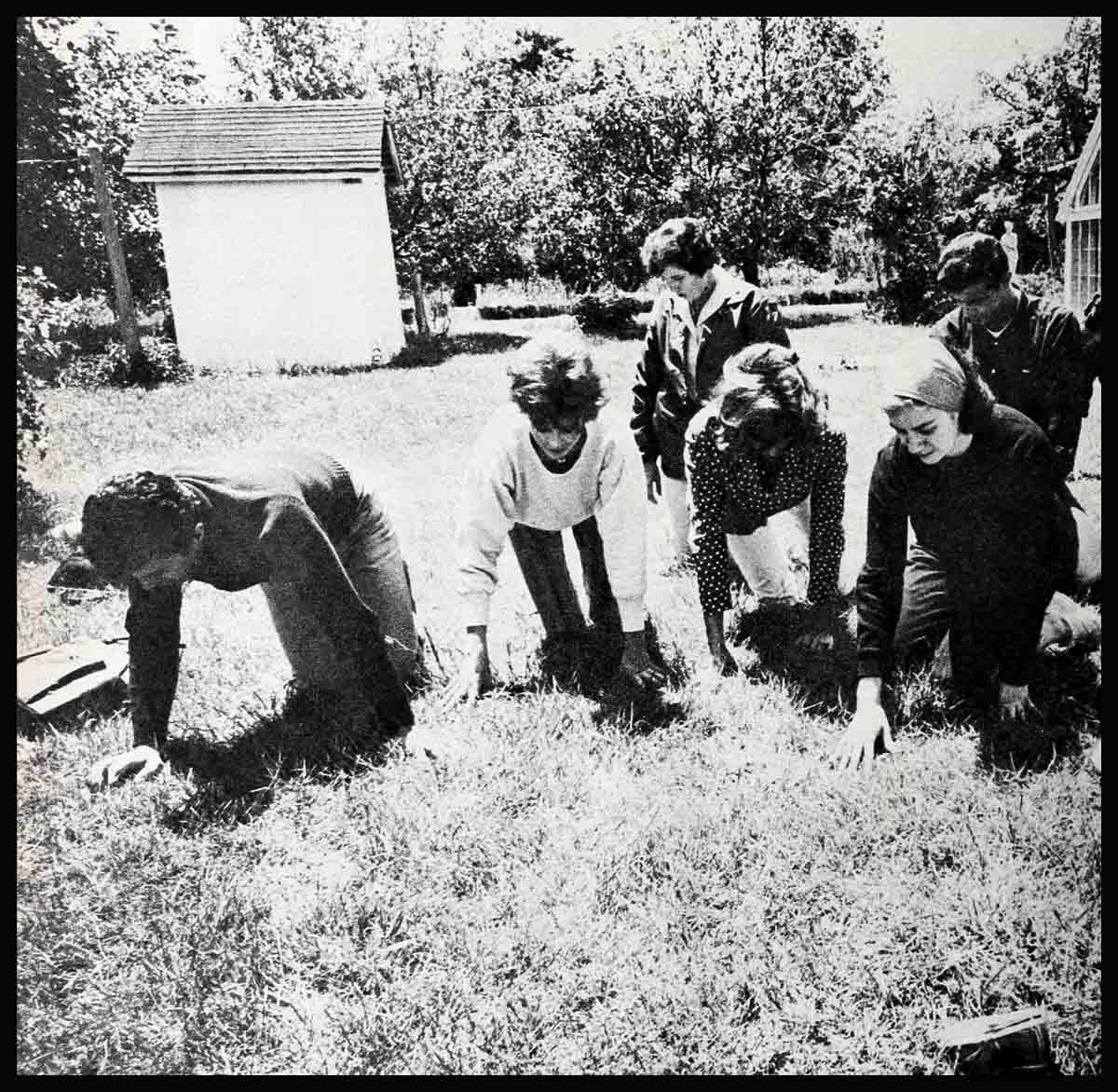

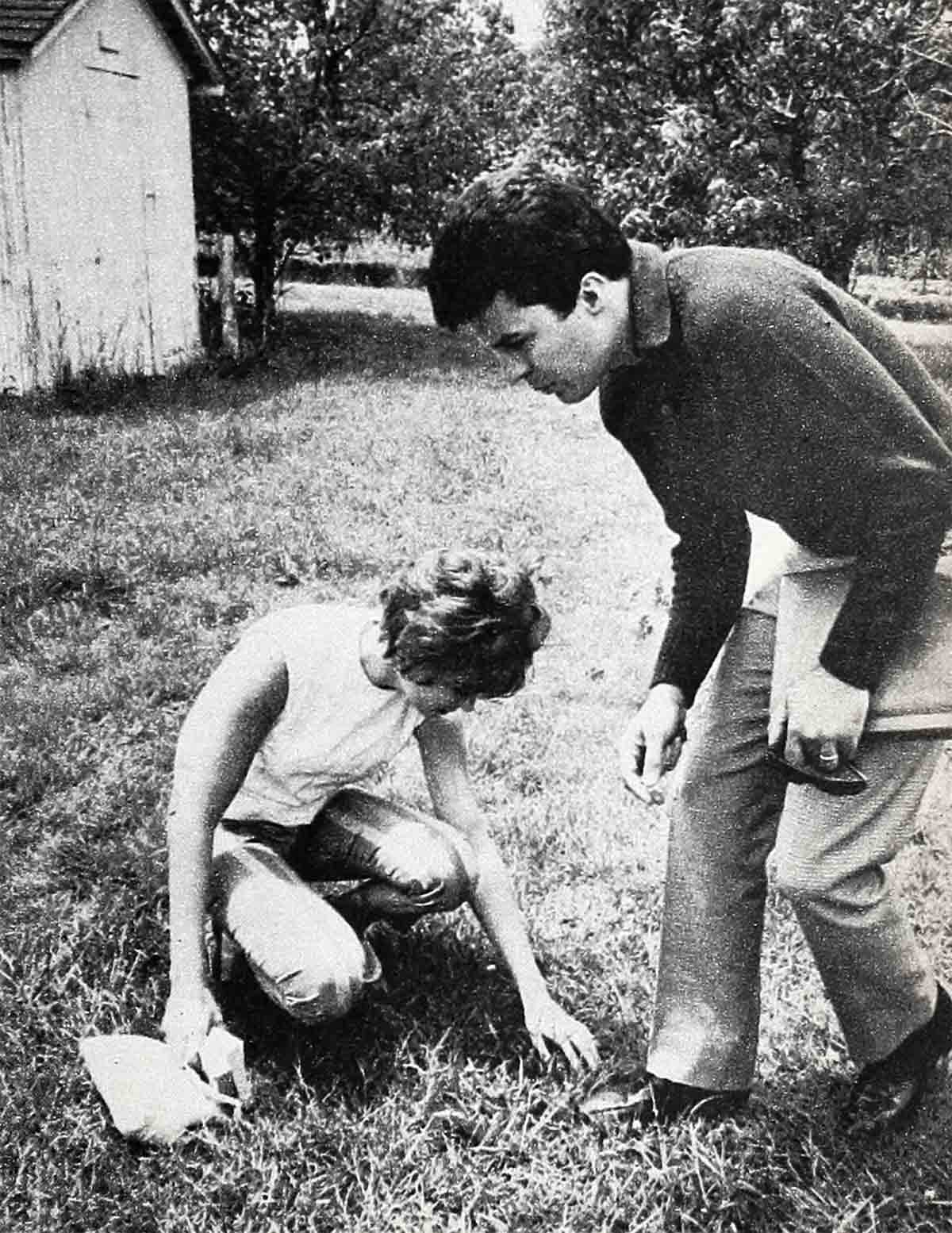

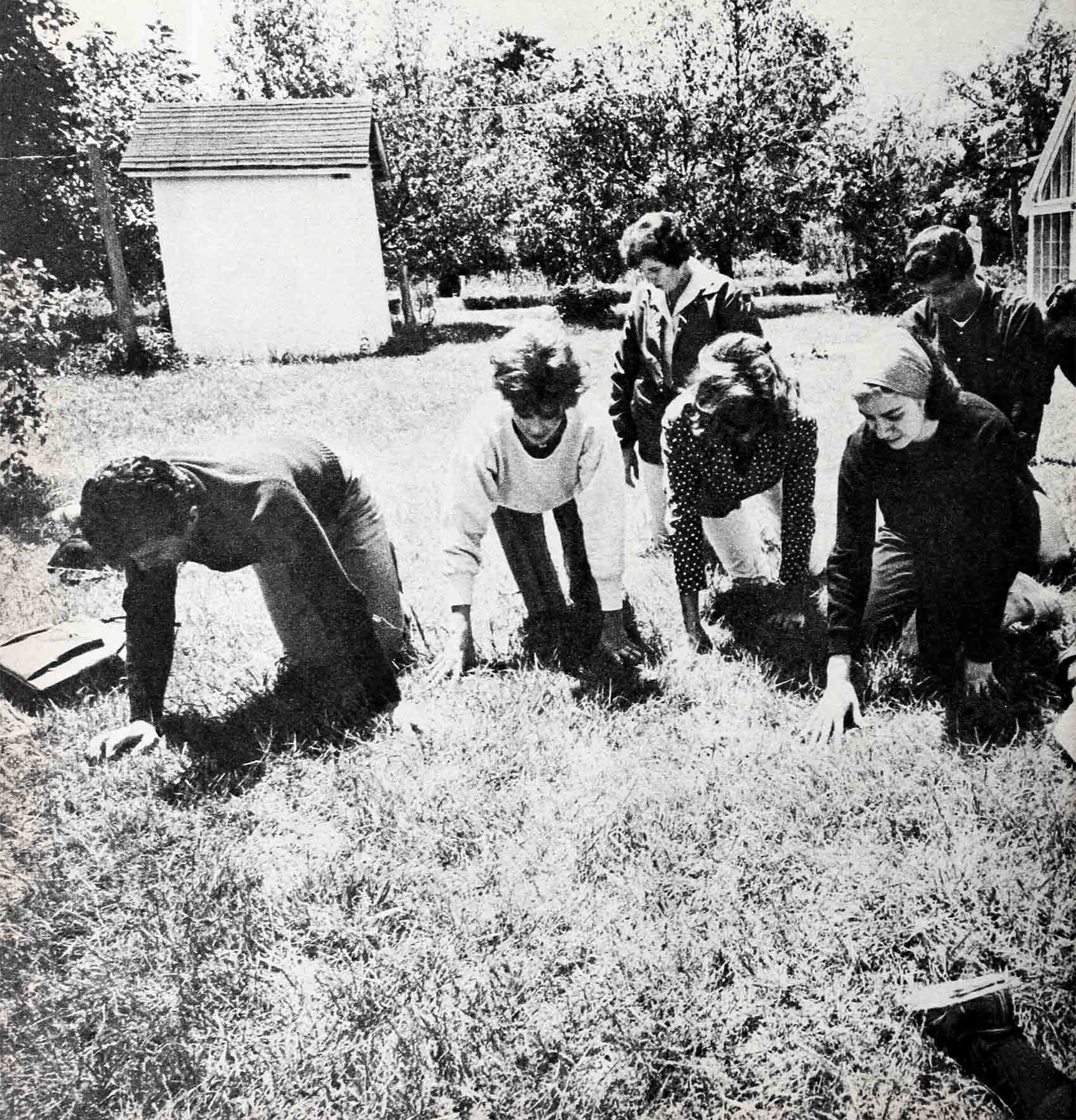

What are all those people doing down on their hands and knees? Playing charades? If it’s just charades, then why do Jimmy and Evy Darren look so unhappy? You’ll never guess the answer, for though the situation looks funny, it isn’t. It represents the first crisis in the Darrens’ two years of married life.

These photos were taken at Bellport, Long Island, a quiet community about sixty miles from New York City. The girls and boys on their hands and knees are, like Jimmy, members of the cast and crew of the Gateway Playhouse, a summer theater in Bellport sponsored by Columbia.

The Darrens’ three- week stay there, while Jimmy starred in “Under the Yum Yum Tree” with Debbie Walley and Nancy Kovack, was to be filled with sun and fun. With only one performance of the play each night, the Darrens had all day to be together. “It will almost be a second honeymoon,” laughed Evy. Almost, but not quite, for disaster struck. To find out what everyone is frantically doing here.

Evy Darren crossed and recrossed her slim, tanned legs, ducked her blond head to hide a guilty yawn and tried once more to watch her husband up on the stage with Debbie Walley, Nancy Kovack and the director.

Here it was, just the second day of rehearsals in the big barn at Bellport, Long Island, and Evy already knew everybody’s lines by heart. Her eyes rested on Jimmy’s handsome face, then inched past the row of front seats, up, up to the round clock on the wall. Twenty-six minutes to eleven. The voices buzzed on, the room blurred, and the next thing Evy knew, she was tiptoeing out the rear door of the theater.

Outside, the sky was black. No stars, she thought. Not even one single little star to wish on . . . It’s so dark out here!

The lawn, an expanse of high, overgrown grass, disappeared into dark shadow. Thick clumps of old trees hid the other buildings clustered around Bellport’s summer theater colony. Evy stood still and breathed deeply the moist night breeze salted with sea air. Hmm, she thought, it’s going to rain.

She sighed and stepped down into the cool, dark grass. She thought of her son, Christian, and how he was probably sound asleep at Jimmy’s mother’s house miles away in New Jersey. She felt a sudden urge to be cuddling her baby safe and snug in their own apartment in California. She was a little restless, a little bored. The stay in Bellport was to be a precious chance to be alone—almost a second honeymoon—but so far Jimmy had been locked up in a prison of rehearsals, cafeteria meals and hours of studying lines. All she had done—all she would do for the rest of the week—was sit patiently in the rehearsal hall and, peep at the clock.

Deeply in love with her husband, Evy tried to push down a nagging little question: Does he take me for granted?

She tried to brush the thought aside and began to toy with the thin, simply carved gold band on her third finger, left hand. Hardly noticing how easily it moved, she twisted the ring, pushed it up to the tip of her finger. Absentmindedly, she twisted it around.

Evy had lost weight since Christian’s birth nine months ago. She thought vaguely how all three of her rings seemed loose—the wedding band, the plain curved fifth-finger ring from her parents, the tiny pearl and gold ring Jimmy had bought her in England.

Suddenly, the door swung open and the cast emptied out, calling good night and walking toward the dorms.

Jimmy stopped under the bare porch light with the director. He looked around and called, “Evy?”

At that precise moment, Evy felt the ring slip out of her grasp. She held her breath, felt her fingers. It was gone.

“Jimmy,” she said, and walked out of the shadows.

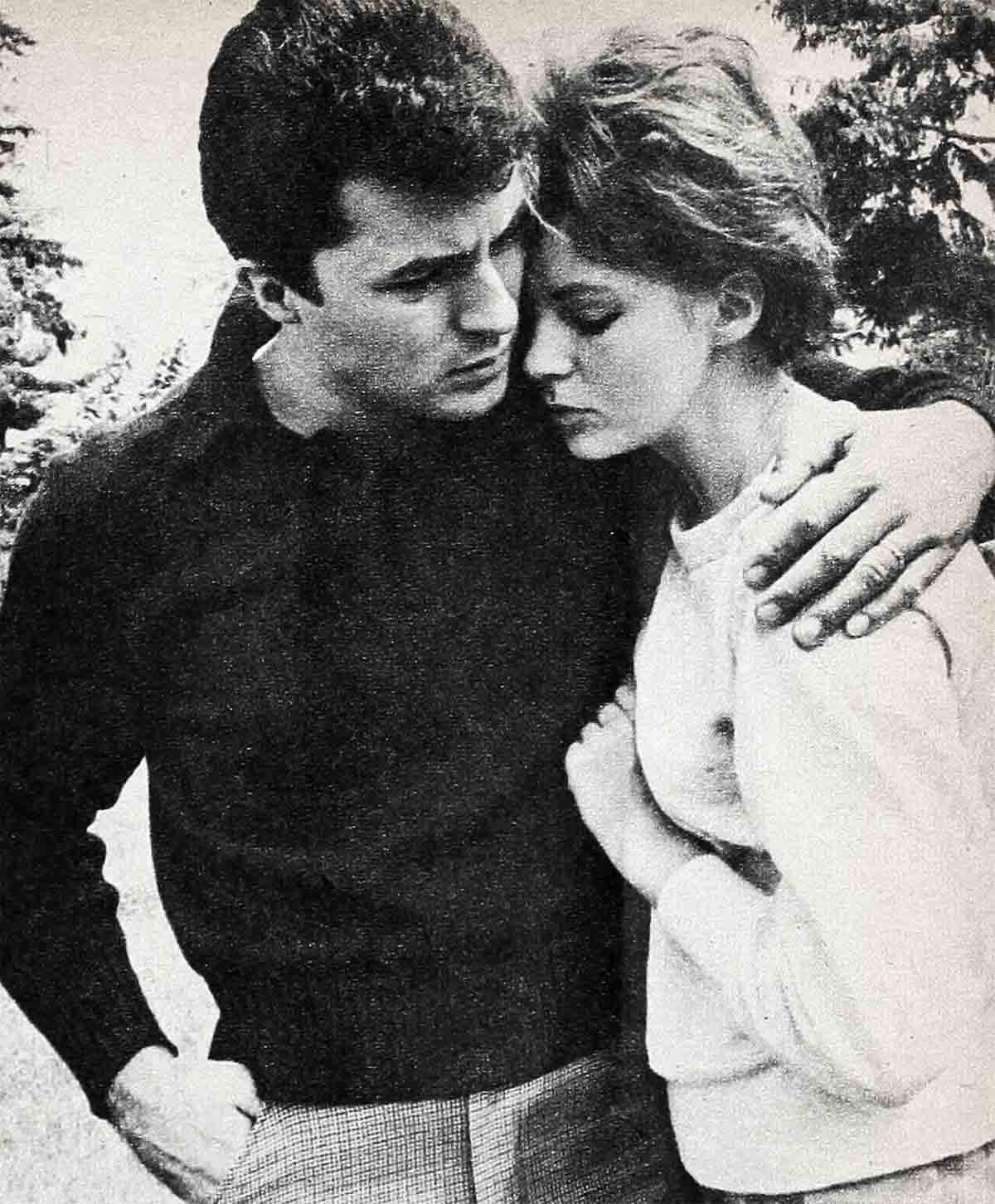

He put his arm around her, then picked up the conversation with the director.

“Jimmy,” she repeated quietly. At first he missed the urgency in her voice.

“Jimmy, wait,” she said.

“What’s the matter?” He turned, smiling.

The director smiled, too. They looked at her, waiting.

“My ring,” she said. She held up her empty hand, like a confused child.

“Where is it?” he asked, still smiling, not understanding.

“It’s gone. I dropped it. Over there in the grass.”

“How could you lose it?”

Instantly, she realized she never should have moved from the spot where it fell.

“Lost it? How could you lose it? That’s impossible,” Jimmy said. The smile faded.

“No, it’s true. I was playing with it. Since I lost weight—I can move it around. Sometimes, when I wash my hands, it almost slips off . . .”

“Where did it fall?”

“There.” Evy pointed to the tall, dark grass. “It’s right there . . . somewhere.”

Her voice faltered. She shivered, looked up at the black, starless sky. Then she felt a drop of rain.

“It’s starting to rain,” Jimmy said irritably.

“Yes,” she said softly, “I knew it was going to.”

“Let’s get some action,” the director said brightly. “We’ll find it in two minutes. Then we can get some sleep.”

He took out a pack of matches. One by one, he struck them, and held them above the grass.

“Here?” he said. “Here?”

“Yes,” Evy said. She retraced her steps. “I came down the stairs. I walked here . . . no, here. It was so dark . . . The grass is so tall . . .”

“Here?” the director kept saying, lighting one match after another. “Here?”

Evy got down on her hands and knees. She pushed the grass apart. She felt the stubby rough roots, the little smooth pebbles, the moist black dirt. She picked up tiny pieces of twigs and splinters, then dropped them in growing despair.

“It’s too dark,” Jimmy said after a few moments.

“Wait till morning, when it’s light,” the director said. He stood up. All the matches were gone.

“That’s right. We’ll find it in the morning.” Evy got up off her knees. She brightened. Tomorrow the sun would shine, the ring would glint. She sighed with relief. Then it would be over. Her ring would be back on her finger where it belonged, where she had never worn another. She would never play with it again.

She kept the good, hopeful feeling all the way to the car. She leaned back against the seat.

Jimmy started the engine, gunned the motor, jammed down the accelerator. As the gnarled shoreline trees sped past, Evy gazed at her left hand. “I know we’ll find it,” she said. “It’s right there, of course, where I dropped it.”

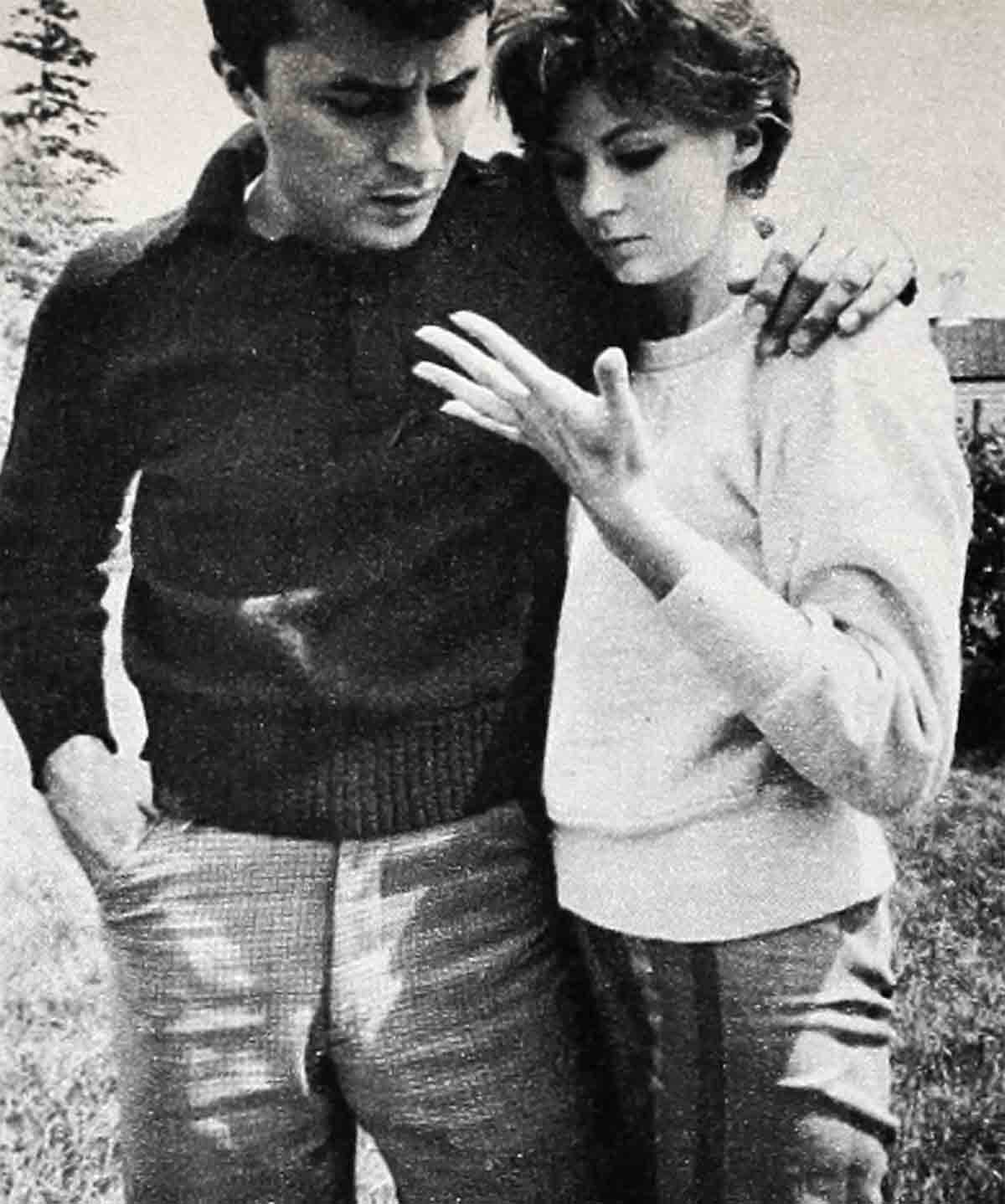

Then she looked at his face. His dark eyes were fastened hard to the road, his jaw tense, his lips tight, as if he were trying to keep from saying something.

“You’re angry,” she said, her soft Danish accents softer than usual.

There was no need for him to answer. It was all there in his face—anger, irritation and sadness, too.

“You’re not superstitious, are you, Jimmy?”

“Of course not,” he said gruffly.

“That’s good,” she said. “I don’t want you to worry about bad omens. You know, it takes more than a ring to bind a man and woman together.”

Jimmy was silent as they walked into the motel together. Just to be safe, she set the alarm a half hour early so she could find the ring and have it safely back on her finger before they went in to breakfast.

After all, she thought as she drifted into sleep, it had been blessed by the priest . . . it was the most precious material symbol of their love, their unity and their whole future together. That was why, without a doubt, she would be sure to find the ring right away in the morning . . .

The first thing you see of the summer theater in Bellport is a big, beautiful gateway from which the theater gets its name, and a long circular drive. At the left is an enormous white wooden house, then a smaller building where costumes are ironed, a greenhouse converted to a rehearsal stage, the owner’s house and office and on the right, a big barn seating nearly 300. One wing of the barn is a dorm for girls.

At 8:30, 2:30 and 6:30, a large rusty bell over a well calls the people to breakfast, lunch and dinner. Classes are held between meals in the barn theater.

In the early morning, the fresh smell of just-made coffee has not yet floated out of the kitchen to the dorms, and the air is still quiet enough to make you think you can hear the sea lapping the beach a mile away.

It was on such a morning that Nancy Kovack, a tall, lovely brownette with the figure of a goddess and the personality of a girl who works hard and honestly, left the dorm, walked along the crunchy drive past the rehearsal hall and saw Evy Darren bending over the tall, tangled grass.

“Hi.” Nancy said, and walked on.

“Hi.” Evy replied, still combing the grass furiously.

Thirty minutes later the breakfast bell rang. Evy stayed where she was, head bent, hands searching through the wet grass.

At 9:30 the cafeteria emptied. Nancy walked back past the hall on her way to class.

“Find any?” she asked.

“What?” Evy replied, still not looking up as she answered.

“Four-leaf clovers.”

“Oh . . .” Evy sat back in the grass, folded her hands and laughed with a strange mixture of good humor and desperation.

“It’s not that,” she explained. “It’s my wedding ring.”

A few minutes later, a group of apprentices noticed the two girls looking through the grass. They joined the hunt. By the time Jimmy arrived, the entire cast was out on the lawn, on hands and knees.

At 10:30 a man with a power mower arrived and began to cut the grass.

“Not here,” Evy begged. “You’ll break the ring with the blades.”

He shrugged his shoulders and moved on.

By noon. Evy was alone again. The others promised to help later that afternoon.

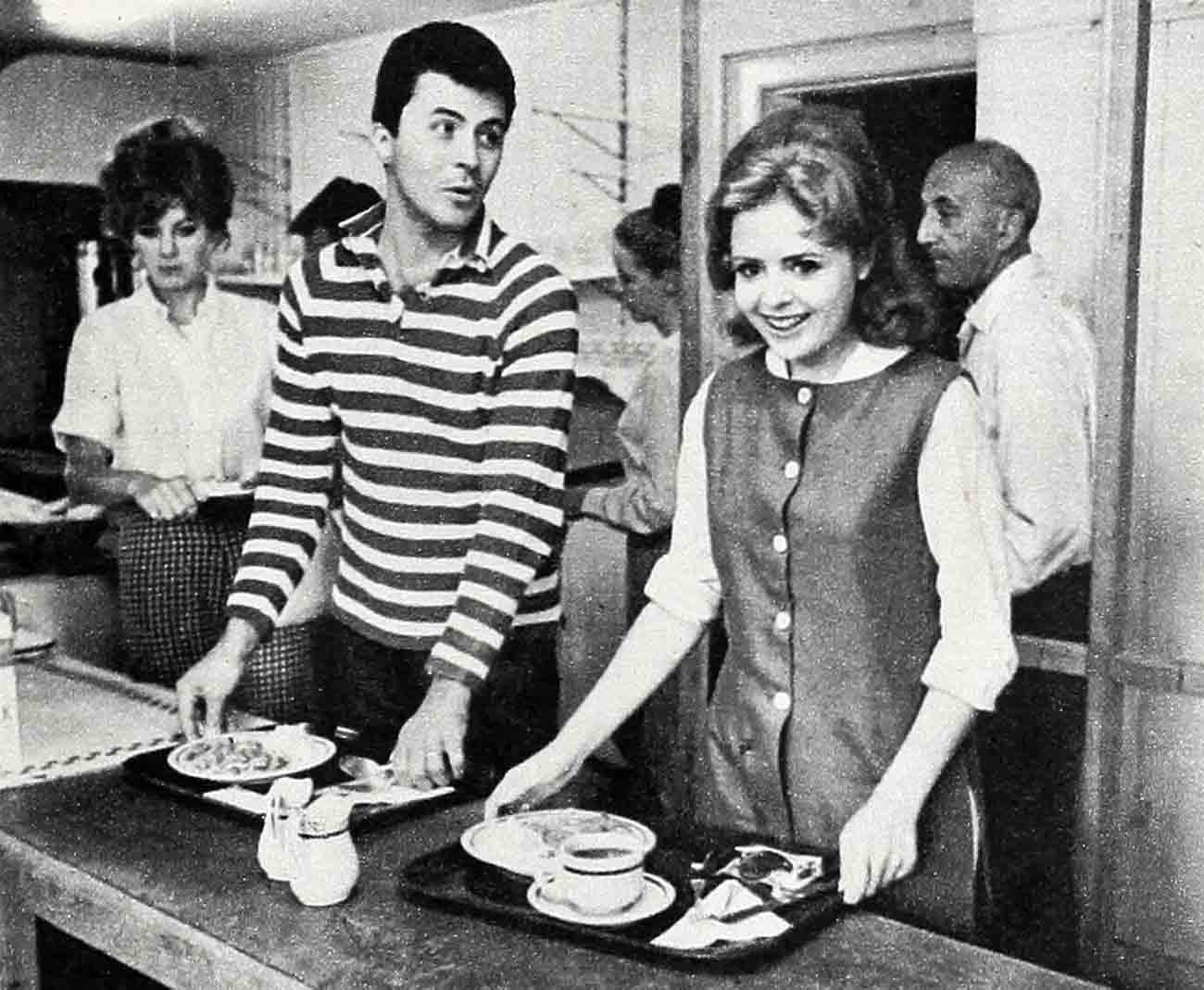

At 12:30 she walked slowly into the cafeteria. Jimmy was waiting at their table. He looked up and she shook her head. He was really angry now.

“It’s there. I know it’s there,” she murmured, forcing herself to eat.

“How could you play with a ring?” he demanded.

She felt hot tears burn her eyelids. She looked down at her plate, then at her bare hand on her lap.

The sun had been hot and strong. Her arms and hands were golden with color. The place where the ring had been was already pink. Later it would turn golden tan like the rest of her hand. Soon the narrow pale band would disappear, just as if it had never been there at all.

Evy brushed at her eyes. “I know you’re angry,” she said. “And sad. I am sad, too.”

Jimmy frowned. “Remember how we went to that little store in Philadelphia? They knew me since I was a little kid. Remember how much fun we had picking out our rings?”

Evy smiled. “Yours so broad, to go with your big hand.” She looked fondly down at Jimmy’s wedding band. It was carved with an intricate design of tiny little leaves—exactly as hers had been carved.

“And yours, so little and delicate.” They both glanced at the empty spot on Evy’s finger.

“And then we were married—and it was blessed.” Jimmy’s voice trailed off unhappily.

After lunch, Evy went back to hunt. A week later, she finally asked to have the grass cut, hoping that would change her luck.

By the second week, she had almost given up. Jimmy told her the ring was gone for good, but now and then she would sneak back to the spot by the stairs and start all over again.

At the end of the third week, the show closed and they packed to leave for New York. It was only when they climbed into the car and drove away from the motel that Evy admitted defeat.

As they drove past the theater and the rehearsal hall for the last time on the way to the city, Evy said, “Jimmy—stop.”

He kept driving. “No,” he said firmly. “It’s gone.”

“But I know it’s there.” she said sadly. “It’s got to be there.”

Jimmy kept driving.

Finally he broke the silence. “The first thing we’re going to do is call Philadelphia.”

“What?” she said.

“To order you a new ring, of course.”

“Oh,” she said, not sure of how she felt.

“It’s going to be just like the other one,” he continued in a firm, almost bossy voice.

She nodded.

“But this time—it’s going to be bigger.”

She gazed at him meekly.

“And wider.”

She looked over at him. He looked angry and sounded angry. She started to get angry, too. How about her? She had feelings, too.

Then, with a shock, her anger changed to happiness. She felt really happy for the first time in weeks. She had never dreamed it would mean so much to Jimmy. Now, in the car, it was as if they were going steady again. She was more than his wife and the mother of his child. She was a woman, and he wanted her to belong to him, to wear his ring so all the world would know.

“And when you get the new one, don’t play with it. A wedding ring is not a toy!”

She smiled at him. The second ring would never mean quite what the first one did, but it would have its own—in a way more precious—significance.

“Do you think because it’s wider, we’ll be more married?” she asked innocently.

“Of course not,” he said sternly, but his face began to soften.

She leaned over, kissed his cheek and cuddled against his shoulder.

The ring, her wedding ring, was still there, where she lost it. She was sure of that. And she would always feel a tug at her heart when she thought about it, buried in the grass at Bellport.

But if I hadn’t lost it, she told herself with a secret smile, I never would have known.

It was nice to find out, after two years of marriage, that your husband cared—more than ever . . .

THE END

—BY BARBARA HENDERSON

See Jimmy in Columbia’s “Guns of Navarone” and in “Gidget Goes Hawaiian.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1961

zoritoler imol

30 Temmuz 2023This is a topic close to my heart cheers, where are your contact details though?