On His Own—Mario Lanza

The news of his firing came to Mario Lanza like a thunderbolt.

He had just finished a transatlantic telephone call to a friend in London. “Look,” he’d said, “it’s definite. It really is. I go back to MGM on May 5th. Exactly when the studio will start up The Student Prince again I don’t know. Joe Pasternak, the producer is going to Italy to do Flame And The Flesh with Lana Turner. But it’s all set. I go back on salary May 5th. When Joe comes back from Italy, probably in July, that’s when the picture begins.

“Oh, yes, another thing. I spoke to Vic Damone today. He told me that he and Jane Powell had been testing for The Student Prince. This I can’t understand unless the studio feels I’m not to be trusted, that I’ll walk off the picture. They don’t have to worry. I’m going to give this one everything I’ve got. I’ve told that to all the executives, and I’m sure they believe me.”

While Mario was talking with such unbridled enthusiasm and happiness, his mother-in-law was trying to get through to him from Chicago. She works at Marshall Field, the well-known department store, and as soon as any news or gossip about her famous son-in-law breaks in the papers, any one of half a dozen salesgirls comes running to her with it.

Five minutes after he finished his London call, Mario picked up the phone in the study of his Bel-Air mansion. His mother-in-law had gotten through. Her voice was charged with emotion.

“It says in the papers,’’ Mrs. Hicks began, “that the studio has fired you.”

Mario laughed. “What papers?”

“All the papers, Mario. The Tribune. All the papers.”

“It must be a joke, Ma. I just finished a long legal hassel with the studio. Everything’s fine. I’m going back to work in a couple of weeks.”

“But the newspapers . . .” Mario’s mother-in-law insisted “. . . it sounds very official.”

“Okay,” Mario said. “Read it to me.”

Mrs. Hicks read the official studio announcement to the effect that MGM could no longer put up with Mario Lanza’s demands and was terminating his employment contract.

Mario refused to believe it. After all, the papers had been carrying erroneous stories on him for months. This was probably another fantasy conjured up by an imaginative reporter. He handed the phone to his wife, Betty, and walked through the living room, an enormous rectangle 30 feet wide and 50 feet long, to answer the knocking on yhe front door.

Lanza pulled the door back and there standing in front of him, his face ashen white, was Bob Kopp, Mario’s lawyer. “I guess you’ve read the papers,” he said.

In that one moment Mario realized that what his mother-in-law had told him was true. Unbeknown to him, the studio had released the news that it no longer wanted his services.

Mario’s first reaction was one of in potent rage. He raved and ranted. For a week he had given a lengthy legal disposition to Loeb & Loeb, the MGM lawyers. For a month his own agent, MCA, had been negotiating in great friendliness with the studio. Mario, in fact, had previously signed a letter which said in part, “I shall report at the time specified and I shall perform all duties required of me. . . .”

In writing he had given his word that the studio would have no more difficulty with him. All he wanted to do was to complete The Student Prince. After all hadn’t he spoken to Eddie Mannix, the studio’s general manager? Hadn’t Mannix taken his hand, clasped it firmly and said, “Let’s let bygones be bygones?”

If the studio hadn’t wanted him for the part, why all these involved, prolonged negotiations? Mario couldn’t understand it. He still can’t. If you have it in your mind to fire an employee, why discuss with him his return to your employment?

Mario’s lawyers insisted upon phoning long distance to Nicholas Schenck, chief of Loew’s, Inc., in New York, the corporation which controls MGM.

In essence they told Schenck this: That Mario Lanza had stated in writing his willingness to complete The Student Prince under any conditions at any time.

Schenck said that Dore Schary was running the studio from Hollywood, that he could not intervene, that he could not disrupt his organization by countermanding an order, that if Schary wanted to fire Lanza he probably had just and sufficient cause, and that was all there was to it. Lanza hadn’t been an angel. He had cost the studio thousands of dollars. He had been edgy and temperamental. He had loused up work schedules. He had antagonized fellow employees. True, he had earned some $20,000,000 to $30,000,000 for Loew’s, but Schary was in charge of production, and if he wanted to make The Student Prince with Vic Damone and Jane Powell instead of with Mario Lanza and Ann Blyth, if he wanted to get Lanza out of his hair once and for all, he, Nick Schenck, would have to go along with him.

By last August MGM was pretty well fed up with the Lanza antics. Mario had carried on in the most astounding manner. To astound Hollywood a star really has to be Unique, because over the years, its population has numbered some pretty wacky characters—but never in the history of motion pictures has there been anyone to equal Lanza.

For example, he once hobbled into Dore Schary’s office, broke a cane over Schary’s desk, and threatened to throw the executive out of the window. Schary, who is the kindest, most thoughtful and the most reasonable of all the executives in Hollywood thought for a minute that Mario was joking. But Mario wasn’t. He was deadly earnest. He had been bawled out because of his personal habits on the sound stage and he was furious. In language unrivaled since the dawn of time, Mario proceeded to tell Schary off at which point the vice president in charge of production came to the conclusion that Lanza wasn’t a very rational man. He came to other unprintable conclusions, too. But Schary maintained his dignity.

Lanza did a great deal of boxing when he was a very young man, and potentially in a fight, he is extremely dangerous. One good right by Lanza and anybody can go to sleep for a long time.

Mario greatness lies in the freedom of his spirit and the freedom of his actions. At Metro, he used to amaze people by singing out the window, by shouting across the sound stage, by carrying on in a lusty, humorous, sometime boisterous fashion. Mario has an actor’s sense of humor which many people don’t understand. For example, at the studio he would be walking along one of the corridors of the Thalberg Building. He would run into his producer, Joe Pasternak. Suddenly, the smile on Lanza’s face would disappear, and he would clench his teeth in simulated anger. He would grab Joe by the collar and say: “I’m going to kill you, you dirty rat. You hear that? Kill you. Murder you. Because you’re a spy, a no good, dirty rotten filthy spy for the Hungarian White Sox.”

After a while Pasternak got accustomed to these exhibitions and realized they were jokes, but in the beginning of his relationship with Mario he thought the tenor was serious.

Another time, after he had quarreled with the studio, Mario went to talk with Nick Schenck, the Loew’s executive who likes to be called “General.”

“You can tell those guys at Metro,” Lanza raged, putting on his act, “that I’m a tiger. Do you hear me, General? I’m a tiger and I’ll rip ’em all to pieces.”

Mr. Schenck quietly told “the Tiger” to sit down and talk things over.

Executives put up with such things from Mario because his pictures made a tremendous amount of money. They gave him such directors as Al Hall and Norman Taurog, such scripts as Toast Of New Orleans andBecause You’re Mine, and the pictures always made millions.

Despite all the trouble, Mr. Lanza and the studio made up their differences and might have gone immediately into production—except, according to insiders, for the star’s desire to have the last word. Right or wrong, it is reported that just as Lanza was to report for work, he was told the name of the man who was to direct The Student Prince. It serves no purpose to mention the director’s name, except to say that he has directed many great hits. That he has never directed a top-notch musical is another fact. This, Mario is said to have objected to, declaring, according to informants, that he would work for any director except this one man. To Mario this was a reasonable stand; to the studio it was an indication that even before work started the actor was already beginning to be difficult. Who is to say who was right?

As one executive put it, “These are not times in which we can afford to gamble a second time. After all, we here in the studio are but representatives of the public. We have an obligation to thousands of stockholders. Perhaps Mario Lanza would be satisfied with another director. Perhaps not. It seems to us that if he were sincere, he would not object to placing this picture in the hands of the one man the best brains of the studio have concluded is the man for the job. To put it bluntly, we feel that he should act and sing and leave executive decisions to executives. He cannot seem to realize that we are as anxious to have a hit picture as he is—more anxious perhaps if that is possible.”

So, at last reporting, the matter stood deadlocked. The studio issued another statement saying that this time Mario Lanza was fired for good. Lanza is said to have taken the news with much more calm than anticipated. He was so calm that some people suspected he was secretly delighted despite a lawsuit hanging over his head.

“Just think,” he exulted, “I am a free agent at last. I can make independent pictures. I can go out on concert tours, work on television, have my own radio show again.”

This perhaps is so, but there are many in Hollywood who insist that Mario is whistling in the dark—that so-called Big Money is going to be very careful about investing in so temperamental a man. They say that it is more than probable that Mario will repeat, in some way or other, his past performances—that there is no way of curing his acute distrust of people and the neurotic belief he has that he has been robbed, tricked, abused, and deceived beyond all endurance.

Mario, meantime, is singing a milder tune.

“Long ago,” he says, “I came to the conclusion that I could bring a little joy into the world by singing. That’s my position in life, and I’m happiest when I’m singing, especially when I’m free.

“I’m sorry that my departure from Metro wasn’t an amicable one, but I tried; I honestly did. I was willing to complete the picture anywhere, anytime, under any director assigned to me. The studio might have told me that they didn’t want me under any circumstances, that they’d had enough. It would have saved an awful lot of time and money.

“Anyway, that’s all done with. We’ve got to look ahead. I’ve got my freedom. What am I going to do with it? My voice is better than it’s ever been. I’m in great physical and mental shape. I’ve had several offers to go with other studios or to enter independent film production. My agent is considering them.

“There’s also radio. I want very much to get my radio show going again. The Coca-Cola people who sponsored my program, that was before the studio refused to let me broadcast, have always been wonderful to me. They’re people of stature and understanding, and I’d like to work for them.

“Also on tap is the possibility of going to London and singing during Coronation Week. That’s some time in June.”

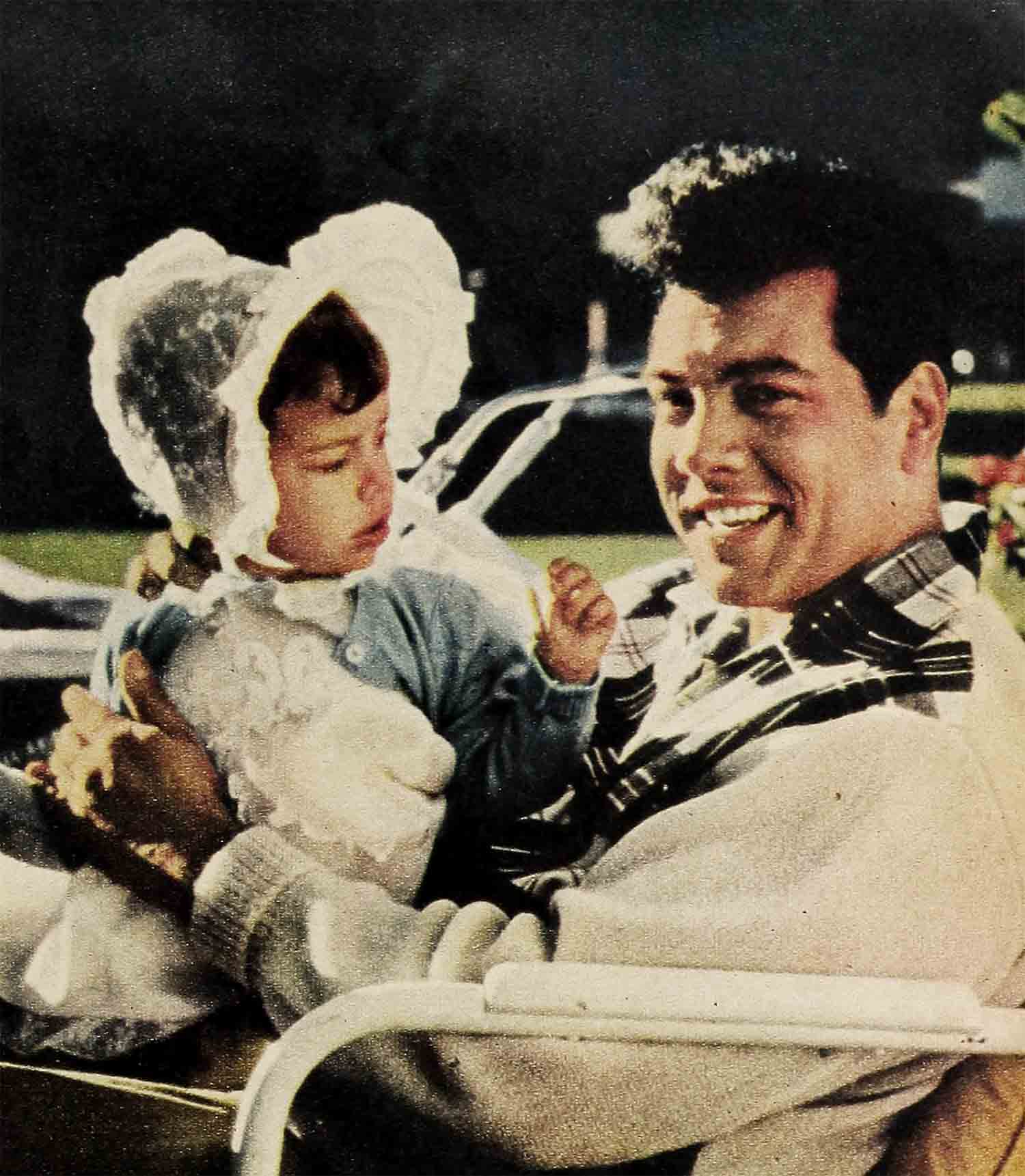

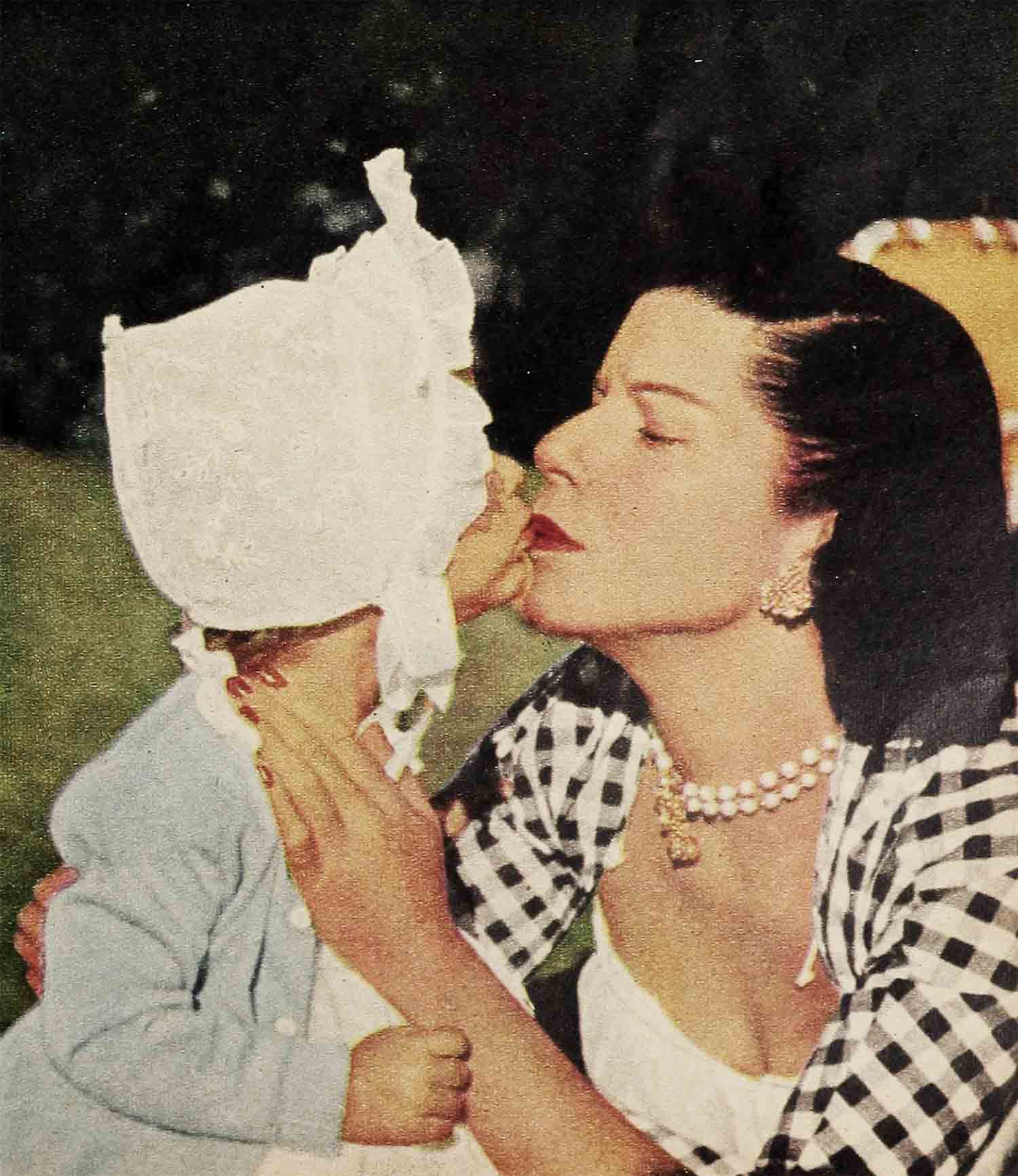

Ever since he and Metro parted, Mario has had more time to spend with his children and to enjoy them. He reads to his daughters, takes them on long drives, spins incredible stories punctuated by operatic arias.

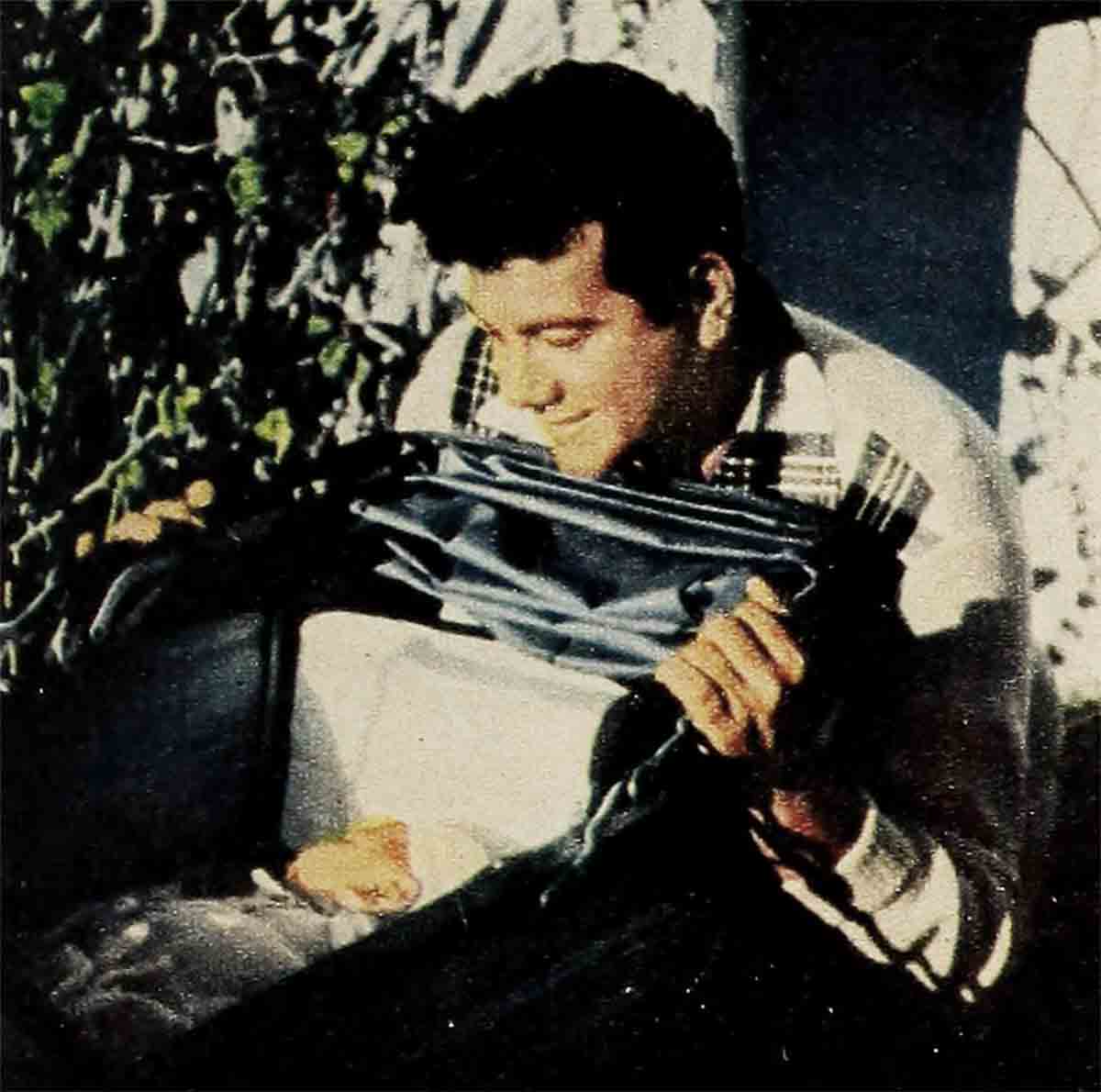

With Damon, however, six months old in June and his only son, Mario is strangely quiet. He wheels the little guy around in his carriage, hums him to sleep, and then sits down beside the perambulator, watching the boy, hoping somehow to protect him from the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” but knowing in his heart that he cannot.

“One of the sad things about growing up,” Mario says, “is that once in a while people hurt you.”

How true that is. All that is left now for Mario to understand is that if he has been hurt he has also hurt others—and for the sake of those who have known and loved him there must come an end to all this. Otherwise, regardless of who has been right or wrong, there will be triumph for no one—only tragedy. He must also understand that this can end only where it began—in the amazing, sometimes delightful and almost always deep and disturbed, mind and heart of Mario Lanza himself.

THE END

—BY ARTHUR L. CHARLES

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1953