How Pat Boone Keeps His Marriage Vows?

All of a sudden there was an awful, endless second of silence in the broadcasting studio. Then the disk jockey’s voice broke through again, a little nervously this time. “Well, Pat, are you? Are you married?”

Pat Boone sat and stared at the microphone—and had to make a decision . . .

His Dot records—then—were just beginning to sell. His name was just beginning to be known. Success, real solid success, could be just an inch away—and it all depended on the kids . . .

The ids would hand him success—or send him back to COLUMBIA U. without a nickel in his jeans. They could make him great if they loved him enough—if enough teenage girls would go on from liking his voice, to loving the dream of him, making him part of their hopes and loves, dreaming him into their lives intimately, personally.

But would they dream about a married man?

Pat Boone stared at the microphone and knew how much depended on his answer.

He didn’t care about being famous. Before God, he didn’t. But he did want security, and a decent apartment—and the rent every month.

And he wanted those things because he did have a wife, and she was going to have a baby.

In that second of silence before he spoke, Pat Boone asked himself what his Shirley really needed. Should he admit he had a wife, and doom her to more years of poverty—or should he deny her, and give her everything that success and money could buy?

And in that same second, the answer was given to him. A few simple words, words he had spoken nearly two years ago. “. . . . forsaking all others, cleave only unto her.”

Seven short words. Yet they told Pat Boone how he would live for the rest of his life—and they gave him the answer he needed now.

He gave the disc jockey a sudden, joyful grin. “Yes,” said Pat Boone loud and clear for everyone to hear. “I’ve been married for a year and a half—to a wonderful girl named Shirley.”

It was as easy as that.

For he knew suddenly that the one thing he always, eternally, obviously owed his wife was to keep the promise he had made her—a promise fifty-one words long and hallowed by the centuries.

“I, Pat, take thee, Shirley, to be my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better or for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health—to love, honor and obey—and forsaking all others, cleave only unto thee until death do us part. . . .”

Fifty-one words. They are no longer dimly remembered. To Pat they are now a creed, the words by which he lives and builds his marriage.

“For better or for worse,” he repeats softly now. “That also meant acknowledging my marriage—even if it cost me some fans, cost us some luxuries or even necessities. For a year and a half my marriage had been this great, wonderful adventure—the best thing that ever happened to me. Then all of a sudden I found out it might have its bad side, too. But does that mean I should admit it existed and hide it when it might get in my way? Listen,” Pat says earnestly, “a vow is a vow. You never get anything good out of breaking a promise.”

For richer, for poorer

He pauses, thinking back. “For richer, for poorer. Those are the next words. Man, there was a time when that ‘poorer’ part meant pretty poor. I was making $44.50 a week on a TV station in Texas when I was going to school down there. We kept everything down to a minimum—including eating. Shirley must have invented eighteen different ways to fix hamburger—and a few more for the times we didn’t even have that.

“Not that you should get the idea we sat around weeping into our empty dinner plates. We got our kicks. I remember one time, one evening when we’d been invited to a party and Shirley got into her one good dress.

“She waltzed out of the bedroom, twirling around for me to see. ‘Very pretty,’ I told her. ‘Your slip is pretty, too.’

“ ‘Where do you see my slip?’

“Right there, I said, pointing. Shirley looked down and turned purple. There was a beautiful hole in the middle of the skirt.

“She disappeared back into the bedroom and when she came out ten minutes later, the dress had a tuck where no other dress I ever saw had one—but at least you couldn’t see the slip. And besides, I walked in front of her all night.

“Personally, even when things were at their worst, clothes were never a problem for me. I had a good wardrobe when we got married and I didn’t change size, so I just kept on wearing what I had.

“Shirley started out okay too. but she did change size. We stuck to the budget, though, and she went through her first pregnancy with just two maternity dresses and the biggest grin you ever saw.

A man’s job

“Now, thank God, we’re in the ‘for richer’ part.” He sighs happily. “So far, that hasn’t thrown us, either.”

Nor is it likely to. You know that, knowing about that time Pat won’t tell about. That time you hear of only from one or two of his closer friends.

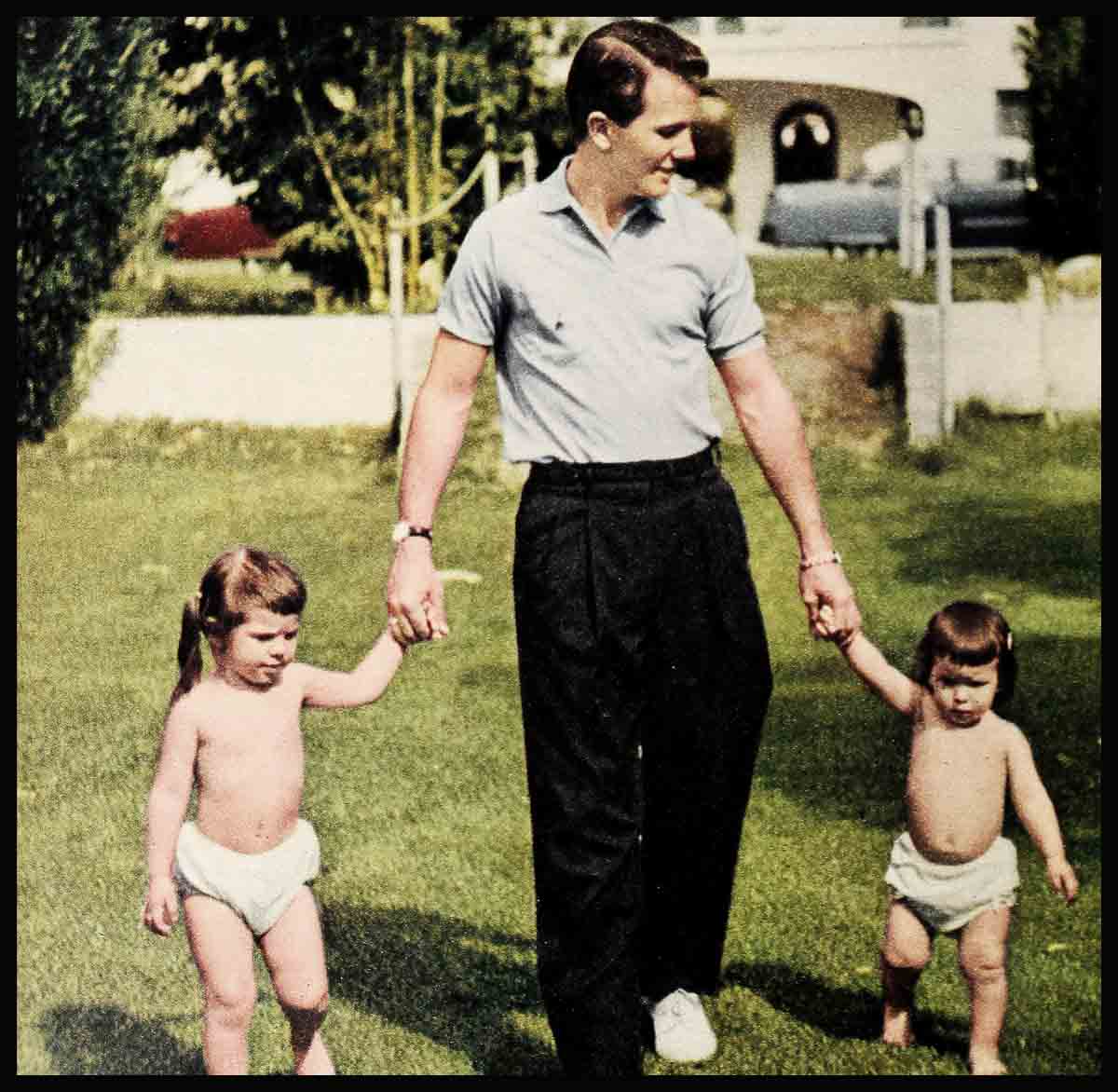

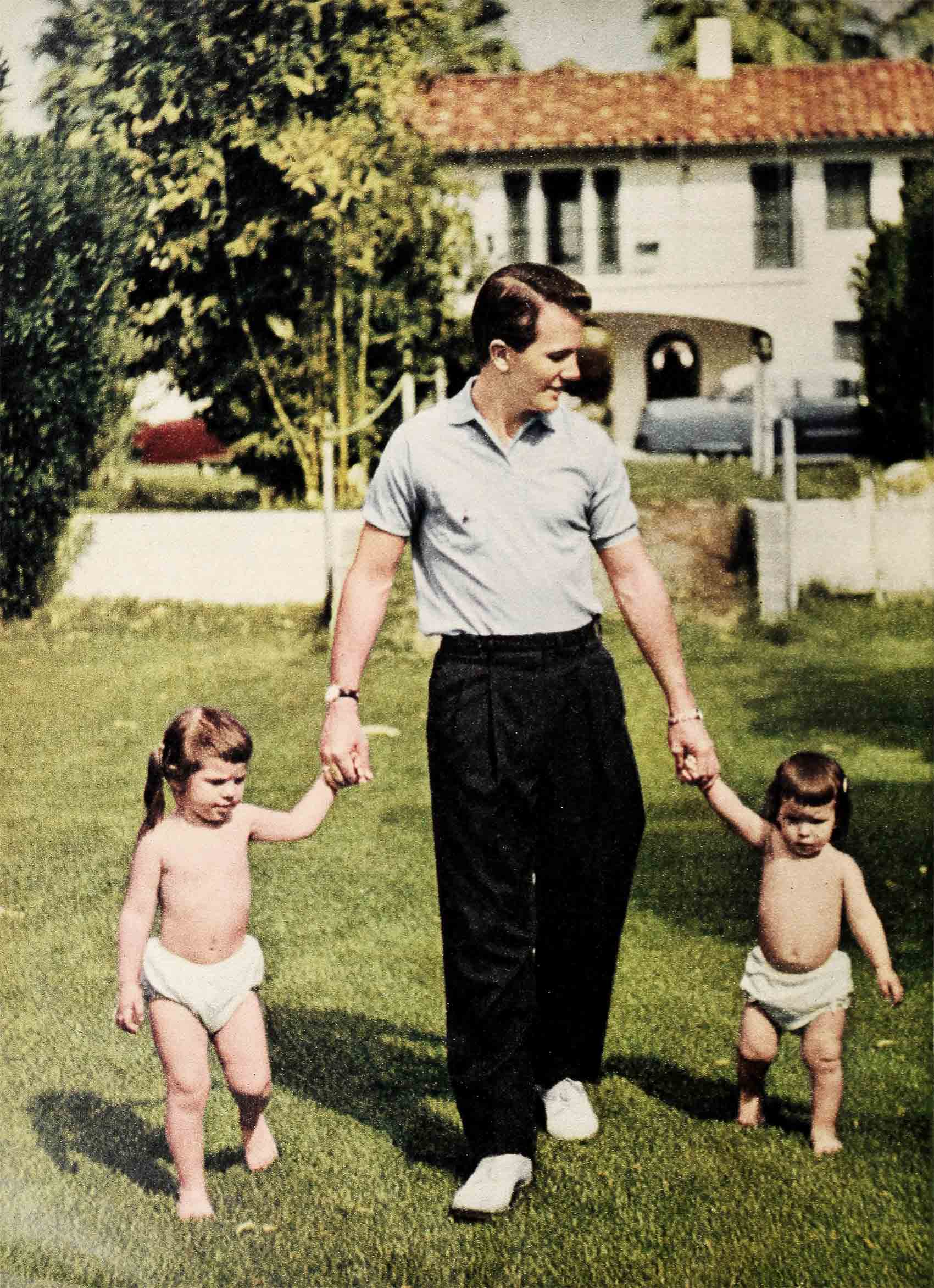

It happened when the Boones hit Hollywood—Pat, Shirley and the three kids. The studio had found them a couple of hotel rooms and moved them in. Pat looked around. It was all very luxurious and room-service-y. But where was the back yard full of dandelions for Cheryl Lynn to run through and plop on her tummy in the middle of? Where were the private, personal doors for Linda Lee to slam and the back yard full of California sunshine for Deborah Ann to coo in? Pat paced the two-inch-thick carpets for two days and then made up his mind.

Usually the most cooperative of people, he begged off all extra-curricular activities at the studio for three days. He turned down luncheon interviews and turned a deaf ear to people who begged him to meet important contacts. Then in a burst of know-how he informed the studio that he had “important business conferences” and disappeared entirely.

And for three days, he house-hunted.

On the third day, he found the perfect back yard, inspected the house attached and approved it, and moved his family in. Then, exhausted but happy, he phoned the studio he would report bright and early for portrait sittings, costume fittings or anything they might have in mind.

It had never occurred to him that with what he was making now he could have hired a nurse for the kids and turned the house hunting over to Shirley and an agent. He hadn’t thought of it because it’s a man’s job to find what’s right for his family—his wife, his children.

Love, honor and obey

No, money isn’t going to get in Pat Boone’s way. For richer or for poorer, his marriage is his business, and he handles it himself.

“In sickness and in health!” Pat says soberly. “Until death do us part! The most solemn words of all. It’s funny how little meaning those words had for us when we said them. Death seemed such a long way off, sickness something we knew so little about.” He shook his head slowly. “It’s different now. You can’t go through four years of a marriage that brings three little girls into the world without developing a new awareness of life—at both ends, birth and death.” And you can see the memory in his eyes of the times he feared that he might know of death through his loved ones.

His eyes were soft and thoughtful. There was no hesitation in his voice. Success will never be Pat Boone’s excuse for avoiding trouble. Crisis will find him where he belongs—at home, with his family. Then the shadow passes and Pat was grinning again, his eyes sparkling. “And then comes ‘love, honor and obey.’ Now, there’s a question for you! Loving and honoring—that’s no trick. But—who, may I ask, is supposed to obey whom? After all, we both promised!”

He put his hands behind his head. “I remember one beauty of a fight Shirl and I had. We were still in Texas then. Cherry wasn’t even crawling yet and Shirl was pregnant with Linda. And all of a sudden my bulging wife comes up with the idea that the one thing she’s got to do is see her father in Springfield, Missouri.

“ ‘Sorry, sweetie,’ I said. ‘I’d take you if I could, but I can’t get away from school right now.’

“So who asked you?’ says she. ‘I’ll go myself.’

“ ‘Go yourself?’ I yipped. ‘Are you nuts? If Cherry isn’t falling out of the car window, that baby—even though it isn’t born yet—will be kicking the steering wheel!’

“ ‘It’ll be a nice, relaxing trip,’ she said. ‘I’m perfectly capable of handling one child . . . and a half,’ Shirl answered me. ‘And I’m a grown-up woman, and I’ve got a right to take a little trip to see my own . . .’

“ ‘You’re a pregnant woman,’ I shouted, ‘and you’ve got no right to do anything that could be dangerous to your health! And besides the car isn’t in such good shape! And what if you blew a tire and what if—’

“And so on till we wore ourselves out and I went for a long walk around the block to cool off.

“I did a lot of thinking on that walk. I wanted to be fair. I didn’t just want to boss my wife around. I wanted to do what was right. So I thought about it some more. And,” Pat grins, “I came to the conclusion that the one who was right was me. And she didn’t go.

“Instead, her father came to see us!

“That’s about the status quo. I’m the boss—as long as I’m right,” he laughs good humoredly.

Then the smile fades and a serious look comes over his face. “But if I’m going to make the decisions, it’s up to me to make sure I have the right facts. So I’ve learned to look at Shirley’s problems through her eyes and take in their meanings and understand her moods when a baby is on the way or she’s had a rough day with the ones who’ve already come.

“But is it worth it? We eloped, you know, and our parents disapproved of our getting married so young. We’d have to work twice as hard to prove to them we were right, never give them a chance to say ‘I told you so.’

“But that’s not all of it any more. I think the more you do and the harder you work for anyone and anything, the more love you build up for them.

“All you have to do is keep your promises. Cherish her and love her no matter what happens, in sickness and in health, for richer or poorer, for better, for worse . . .”

“And then it just has to be for better—all the time . . .”

And Pat wasn’t even thinking about the time a disc-jockey asked him a question he was afraid to answer. Afraid, until he remembered a promise—and found—in the love of millions of kids—that it was the right answer. . . .

THE END

—BY VI SWISHER

Pat can now be seen in 20th Century-Fox’s BERNARDINE and will soon be seen in 20th’s APRIL LOVE.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957