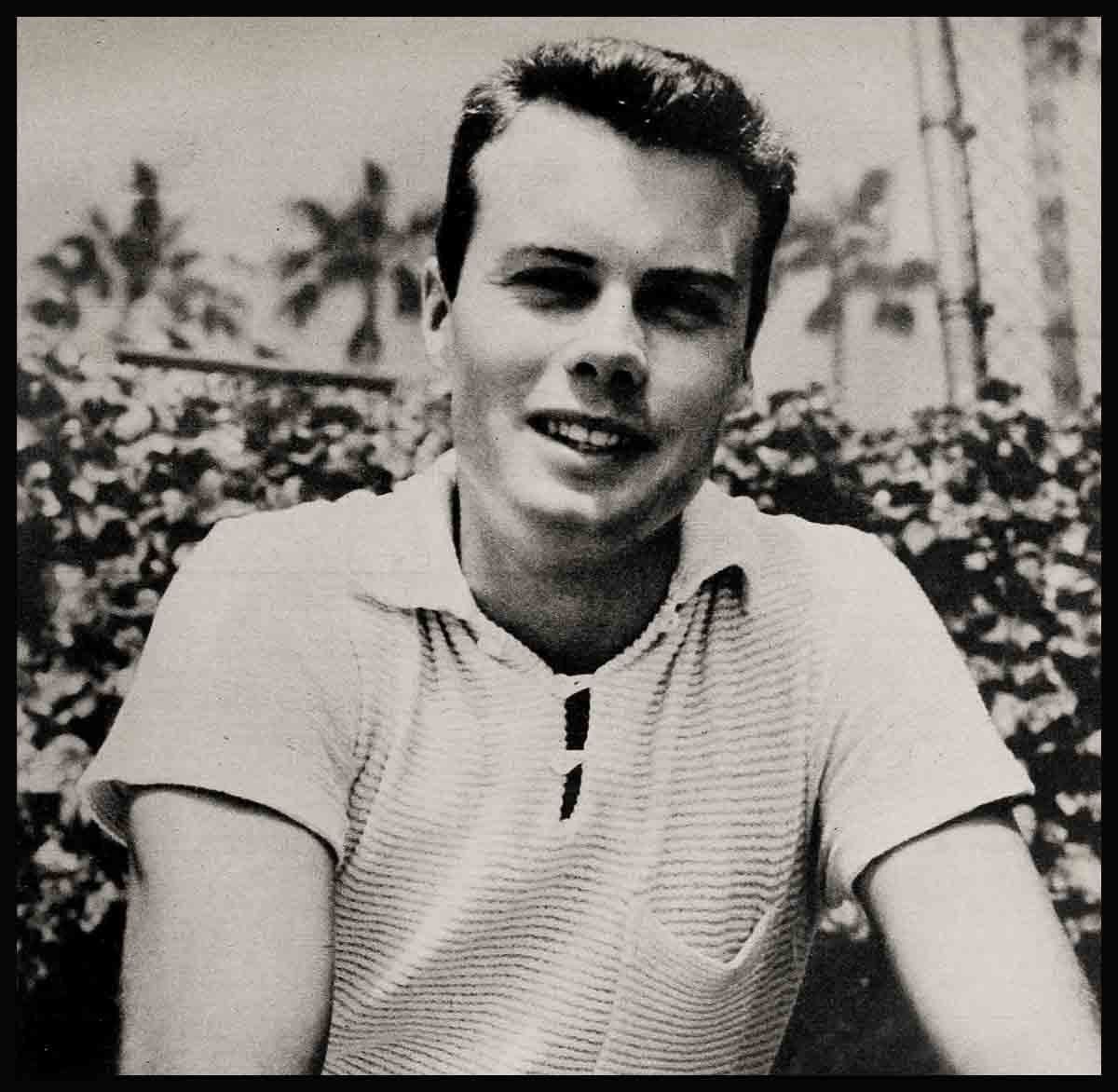

New Faces—Bob Francis

Where did this Bob Francis come from? That is the question Hollywood citizens are asking each other.

One writer was. talking to Columbia Pictures’ publicity department. “I can’t understand how I’ve missed him! What pictures has he made?”

“No other pictures. This is his first.”

“What Broadway plays?”

“He’s never seen Broadway.”

“Oh, I get it,” she brightened, “television!” Wrong again—no TV. Radio? Never in his life.

Stubbornly, she ran out the list: Little theatre? Summer stock? Operettas? Nightclubs? Vaudeville? Circuses? Fairs? Resorts? Modeling?

“You don’t understand,” said the perspiring press agent. “This guy’s brand new. He’s never done anythingbefore.”

The lady snorted. “Do you think I was born yesterday? Don’t give me that Cinderella-boy stuff. It just doesn’t happen in Hollywood any more.”

The outraged cynic was absolutely right. It doesn’t. And yet, to all appearances, it certainly had for the tall, husky and handsome specimen of young American manhood named Robert Charles Francis. The press agent was making true talk. Fame suddenly pegged big Bob Francis right out of left field. Until he took on the prize romantic role of Ensign Willie Keith in The Caine Mutiny, Bob had never earned a nickel from any kind of performing.

If it hadn’t been for a sizzling Fourth of July five years ago, the idea of emoting for a living wouldn’t have entered his head.

Bob Francis had rolled down to the Santa Monica beach with Nanette Burris in her midget Crosley runabout—to make parking easier. But when he tried to park his own long legs on the sands there was barely room in the mob—and how could he ride the waves when the surf was a pudding of bobbing heads?

It took Bob Francis exactly ten minutes to realize that seaside sport on the Glorious Fourth was a bum idea, shake out the beach blanket and drive off with Nanette. Those ten minutes changed his life.

A Hollywood talent scout spotted his dreamboat physique and features and jotted down the license number as the Crosley dug out. Next day he called Nan and Nan called Bob. Today Robert Francis is the hottest young actor in Hollywood.

If you call Bob a Cinderella boy, you’d better smile when you say it. In all this, luck obviously figured but hocus-pocus did not. It took five years of hard study to learn his stuff and prepare for his break. But when it came he was ready, and now that glory’s here he can handle that too. He still lives in the small Pasadena cottage where he grew up with his mother and his postman dad, and a home town girl is still his sweetheart. The nightcap he still prefers is bread crumbled in milk, and he still takes acting lessons twice a week.

Keeping his feet on the ground but also steadily moving ahead has been a habit with Bob Francis ever since he was born in Burbank, California, twenty-four years ago last February 26. “A perfect picture baby,” his mother recalls proudly, “golden curls and all—but with a mind of his own beneath them.”

Nine days after he came home a doting grandmother sewed him a frilly cap and placed it on the ringlets. At an age when most mites can’t raise their arms, Bob shot his up and yanked it off disgustedly. He hasn’t worn a hat since. Nobody around his house remembers a time when he cried either, even when he banged into the furniture. Baby Bob never bothered with crawling; he just reared up and walked.

Bob’s confident, independent attitude toward life traces to a bunch of basic blessings he’s enjoyed all along. For one thing, he comes of sturdy stock. From his parents he inherited bold characteristics and a heroic body. It was a help to have a big brother, Bill, ten years older, a sister, Lillian, eleven ahead, to advance his outlook. “I was an afterthought baby,” Bob grins. “But nobody babied me much.” His dad confirms that. “We looked after Bob, but we let him take care of his own affairs,” he says. “That’s the way to make a boy a man.”

Bob’s dad was an electrician when Bob was born, but three months later when that job ran out, he moved back to his home town of Pasadena and turned postman. Bob grew up in the modest frame cottage his dad built thirty-two years ago.

At both Hamilton Elementary and Wilson Junior High Bob is remembered as a hard-working, good, steady student, the kind of dependable kid that teachers invariably picked as a monitor and street-crossing guard. Being the leader type and big, Bob starred in all the playground sports—football, baseball, track until today he grins honestly, “Sports? You name it, I can do it.” He never missed a Sunday at the First Baptist Church where his pop taught a Sunday School class, also acted as Scoutmaster for Troop 49, B.S.A. Bob sang in the boys’ choir there. For a while, he dutifully plugged at the dancing, piano and violin lessons his mother insisted upon.

What Bob Francis really craved—and still does—was the outdoors. With a Scoutmaster dad and an Eagle Scout big brother, Bob contracted a fever for outdoor life he has never lost. Even several close calls with angry rattlesnakes didn’t intimidate him—or his Scoutmaster father. “I always knew Bob could handle himself wherever he was,” says William Francis. Sometimes Bob’s mom wasn’t so confident.

Like at the beach where the Francis family camped every summer in tents. It’s harrowing for a mother to spy the bobbing head of her twelve-year-old boy out past the breaker line, see him take reckless headers off a thirty-foot pier or watch him ride the hissing crest of giant rollers that could break his neck if he made a split-second miscalculation. Lillian Francis knew what lifeguards meant when they sighed, “I like that kid—he’s got. nerve. But when you people leave—thank God, I’ll get a day’s rest!”

Bob Francis never was in the perilous plight that he seemed to be in eternally. He caught on quickly with the instinctive coordination and savvy of a natural athlete.

Everyone took him for years beyond his age. He was oversized early—six feet at thirteen—and knew his stuff. Once down near Oceanside a bunch of Marines, spotting Bob in his Sea Scout suit, thought he was a gob and invited him back to the Pendleton base. He yanked off the telltale Scout insignia and had a whirl—although his dad later bawled him out for posing for what he wasn’t.

Bob was through high school at sixteen and went to Pasadena City College, although his academic career was mostly a case of going through the motions. He made his grades of course, did all right socially as a “Deezer” (Delta Sigma Rho fraternity) and knocked around with a little football but all the time his heart and mind were somewhere else—skimming mountain slopes on a pair of skis. That was such a big teen-age charge with Francis that it never occurred to him that he might be in anything but the ski business the rest of his life. He hadn’t thought of acting.

“I never was even a bunny in an Easter play at school! I never went to movies. I couldn’t stand to stay indoors that long. Yep, there was the Pasadena Playhouse right in my own home town. Famous too, but I never bothered to look inside the place. Just wasn’t interested—then.”

This skiing kick (which still haunts Bob) started when his brother Bill, an expert, put him on waxed slats at eleven and pushed him down a hill. He almost knocked down a pine tree, but Bob knew right away it was for him. Soon he was racing down the scary slopes of Mount Baldy and winning cups. Nothing much discouraged Bob—not even when in one downhill race he ducked a contestant who crossed his path, broke his pole and ran it through Bob’s arm. Bob finished with the stick piercing his flesh—and won the race.

When Bill returned home from the Air Transport Command after the war, he wanted to open a ski shop in Pasadena with his brother Bob for his partner. “The Ski Cellar” started while Bob was still in school and flourished, spreading to Mount Waterman and Big Pines ski resorts. “We did swell,” remembers Bob, “and then boom—two winters of no snow, hardly a flake! We lost our shirts!”

After this debacle, Bob batted around in a state of confusion as his ski shop dream winked out. Bill got another job (being married, he had to) and today is a successful businessman. But for Bob, “The rug was really pulled out,” he says. “I was a pretty mixed-up boy about then. I wanted to finish college to please my folks and for a while thought I’d go over to Colorado U. But when I leveled with myself I knew I wanted to go there for the good skiing. I couldn’t be a financial burden to them when I wasn’t after any profession. So I just wandered around for a few weeks trying to think things out.” He had applied for a gas station job when that hot Fourth of July steered him to the beach—and that changed everything.

“I figured somebody was crazy,” he grins, “maybe me. But I also thought, ‘Why not? What have I got to lose?’ ” So he called the number and made the date, feeling out of place and awkward.

When he tackled a reading for drama coach Sophie Rosenstein, Bob delivered his lines with all the finesse and feeling of a railroad conductor announcing station stops. Miss Rosenstein had to tell him the truth: “You’re much too raw for us to consider here.” But the attractive qualities that everyone sees today in Bob Francis—his great good looks, manliness and fresh, clean-cut personality prompted a suggestion she wouldn’t ordinarily make to one so green. “You have possibilities,” she said, “and if there’s anyone in Hollywood who can bring them out it’s Botomi Schneider. If you’re serious about this, I’ll call her.” Bob allowed he was, although that was an impulsive statement. In his addled state, he really didn’t know. Nor did he know how lucky he was when Botomi said she’d take him on. But now he knows. “I owe everything to her,” says Bob honestly. “She did it all.”

He calls the Schneiders, Botomi and her husband, Benno, “my second parents.” Botomi Schneider is a remarkable teacher, blessed with the gift of bringing out talent in young people. She has smoothed the rough edges of such stars as Virginia Mayo, Vera-Ellen, Joanne Dru, Piper Laurie, Lex Barker and Tony Curtis—to begin a long list. “I never had a greener pupil than Bob,” she says, “but also never one with greater promise. He was serious, intelligent, quick to learn, and above all, fiercely determined. Besides all that, he has irresistible charm and a natural authority in everything he does. He’s still developing, but someday he’ll be really great!”

When Bob Francis started his acting lessons he was as inarticulate as a cigar store Indian and sometimes got so mixed up in his scenes that he stamped off the stage in disgust. But after only a few weeks Botomi tested him in the role of an artist who suffers a nervous breakdown. “He broke into such convincing sobs and kept them up so long that I became frightened,” she recalls. “After that we both took a phenobarbital and lay down to recuperate!”

Bob himself never had a weak moment, even though it wasn’t all easy. “Sometimes,” he remembers, “it was like slogging along a muddy road with loose boots, never really sure you’re getting anywhere.” It was a long hitch from Pasadena but he managed by bumming rides, borrowing his dad’s Chevvy or hopping a jerky bus. Often he slept in the Schneiders’ guest house, whipped up his own meals there and babysat with their kids, Nina and Tony.

“We looked on Bobbie as our son,” says Botomi Schneider. “He’s the kind of boy you instinctively have complete faith in.” That went for all of Bob’s classmates, too—David Brian, Danny Arnold, Jody Lawrence, Piper Laurie and the rest. As one of them, Don Oreck, who is Bob’s best buddy today, says, “All of us knew Bob was going places even though he hadn’t done a thing. The only question was when.”

Where Bob went first however, was into the Army. Although he expected his “greetings,” it was still a blow. “I thought sure I’d sweat it out in Korea,” he grins, “and I wasn’t sure there would be such an appreciative audience there for what I’d learned.” Instead, he landed at Camp Roberts, only 170 miles north of Hollywood, and found a very appreciative audience indeed.

After his basic training someone read “studying to be an actor” on his papers and they gave him a job teaching diction and public speaking in the non-com leaders’ course. At Camp Roberts Bob ran into his old dramatic school buddy, Don Oreck, and they became barracks bunkmates. Don is a handsome radio actor with an oversized funnybone and a fertile imagination. They turned into unreasonable G.I. facsimilies of Martin and Lewis.

It all started when Don got the reckless idea to break up a certain long and tedious class. He sent for some Nazi uniforms he’d collected at home and the pair put them on after working up a “Heil Hitler” routine that was sheer zaniness. “We stalked into the middle of class one day,” relates Don gleefully. “And the instructing officer almost fainted. But the guys rolled in the aisles. A couple of hams like us went crazy collecting laughs and we really shook the place loose. Then when we were stalking out who should we see parked in the room but three generals—members of an inspection team. Bob stared at me and I stared at him and we both turned green.”

To their immense relief, however, the generals were grinning. “Keep it up, boys,” they said, “you’re great for morale.”

So, while Bob Francis soldiered conscientiously for two years he also kept his talents honed. Weekends he could roll down to Hollywood for a brush-up session with Botomi and some of his mom’s home cooking. Once he almost didn’t make it. The car he rode in slammed into a truck and was completely demolished. Another weekend car crash brought happier results. On leave in Pasadena, Bob saw a car smash broadside and a pretty girl bounce out. He dashed over, picked up the girl, bought her coffee at a drive-in to quiet her shaken nerves. Her name was Dorothy Ross, a co-ed he remembered vaguely at P.C.C. She’s his steady today.

Bob was mustered out in 1952 with no casualty other than a touch of chicken pox to show for it and no particular martial honors except his corporal’s stripes. He took a two-week vacation in Las Vegas without dropping his Army pay savings, then used them to re-enroll in Botomi Schneider’s acting classes. It was a month later that what he calls “That Great Day” arrived—only he had no idea it was dawning. Bob still felt he wasn’t ready to turn pro, and even Botomi, a perfectionist, agreed. But her husband, Benno, who has a steady drama coaching post at Columbia, had other ideas.

Benno knew what headaches Columbia’s talent executive, Max Arnow, had worked up hunting a fresh, typically American young actor to play boyish Willie in the studio’s big effort, The Caine Mutiny. Where to find an unknown who wouldn’t look silly alongside Humphrey Bogart, Van Johnson, Fred MacMurray and José Ferrer? Benno thought he knew where—right at his house. He told Arnow, “I think I’ve got your boy.” Benno doesn’t talk much but when he does people at Columbia listen. “Bring him over,” invited Arnow. Right then Bob Francis had a straight shot at Hollywood’s plum-of-the-year, although he certainly didn’t know it.

“The phone rang a long time before it woke me up. So I was still fuzzy when Benno said, ‘Can you come to the studio at two today and read for me?’ That’s all. I thought, ‘Good. I’ll get inside a studio at last.’ but I also thought it was just for experience, maybe helping some contract girl in a test. My folks were gone and so was the car. I called Dorothy at the Jet Propulsion Lab where she works and she dropped hers off for me at the noon hour. I didn’t bother with lunch, just rolled over when I got dressed—and the next thing I knew I had the script of The Caine Mutiny in my paws, but I still didn’t catch on. I’d read the book in the Army but I didn’t dream anything was there for me, especially ‘Willie.’ That was for someone like Montgomery Clift.”

It took almost that whole day for Bob to figure what was going on around him—and ordinarily he’s not a bit slow on the uptake. But it just seemed impossible—even when Benno took him in to see the studio boss Harry Cohn, and then producer Stanley Kramer who chatted and sized him up for four hours until it got dark and Bob’s empty stomach started growling. Even when he read Willie’s scenes for Kramer Bob didn’t quite savvy. Of course, he didn’t hear Kramer take Benno Schneider out in the hall and whisper, “That’s the boy!”

It wasn’t until they ushered him into the legal department and he scrawled his signature on a test contract that light on what was up began to break. “Then suddenly I got the shakes,” chuckles Bob. “I had an awful time writing my name.”

But those nerves were nothing compared to the next few days of suspense. Next morning he made a test with Donna Reed, the first time he’d ever looked into the business end of a camera. But he didn’t fluff although they were three of the toughest scenes in the script. They flew the evidence to boss Harry Cohn in Hawaii and for the next five days Bob Francis walked around like a zombie. “Those five days were like five years,” as he puts it. But the word came back at last and the word was “Okay.”

Once Bob Francis tackled the serious business of making The Caine Mutiny, however, he settled down, cool as a cucumber. “I’m really not the nervous type,” he protests, “when I know what I’m after.” The fast star company didn’t faze him, nor did the dramatic chores or the love scenes with May Wynn. He’d been prepping three years on his fundamentals. Strangely enough, the roughest job Bob encountered in his picture debut was keeping his carcass all in one piece, never much of a problem to him before.

He spent some bad times aboard the destroyer Doyle lying in his bunk with seasickness, thinking he’d die and afraid he wouldn’t. He had a close shave with sharks diving from the deck off Pearl Harbor and got dumped with 70,000 gallons of water in a typhoon sequence. Probably the worst moment of all for Bob, who is afraid of high places, was the time he had to climb the ship’s towering mast to the crow’s nest as the camera swung 100 feet in the air to record his fright. “Brother, it was plenty real, too,” says Bob. “I tossed my cookies when I got down on deck.” A Columbia publicity man, however, swears the greatest perils Bob survived were 3000 University of Hawaii co-eds who milled around him on the beach at Waikiki!

Sometimes it’s hard for Bob Francis to believe all that’s happened to him is true. But he doesn’t want any of it taken back. “Acting, I love,” he says. “I eat and breathe it. It’s a passion with me now, just like skiing used to be.”

Not one for cities, Bob says, “I’ve got to stretch out sidewise in all directions.” Which is his way of saying he’s still a western boy who needs plenty of room.

For instance, Bob has his suits expensively tailor made, but he has to get a fit for his big frame. Bob Francis has a high disdain for mere money. “Don’t give a hoot for the stuff,” he swears, “except to spend. I’ll never be rich and I don’t want to be.” Right now, of course, he’s not in the blue chips but already Hollywood business managers and agents are keeping his phone hot. He just laughs at their promises of riches. “Call you when I need you,” he tells them, implying that’s a long time off. A soft touch, he’s always getting nicked.

He’s just as relaxed about Hollywood social life. Bob hasn’t shown at a Hollywood party yet although by now he’s flooded with invitations. He’s obliged for a couple of premiéres with Columbia stars and starlets, but tags that in the line of duty. That doesn’t mean he’s a square, just that he prefers to take his fun with the gang he has always known. With them he likes to drive to the beach, desert or mountains, and around town hunts out little clubs and cafes that aren’t show-cases, where when he dances, Bob says, “I can just step out on the floor and float around”—usually, of course, with Dorothy Ross in his arms.

“I have to be secure about myself,” says Bob seriously, “before I think of marriage. Someday I want a house with land around it and plenty of things to fix up for my family and kids. I want to travel and see the world.” He has started seeing it lately. Until Caine Mutiny Bob hadn’t been out of California except to try out some ski slopes up in Utah and Nevada. But now he has been to Hawaii and New York and he is lined up to junket around quite a bit from now on.

Right now it’s hard to see what will keep Bob Francis from traveling fast and far—unless he breaks both legs, which hardly seems likely, as he hasn’t the time to ski. Physically, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with him except a tendency to sleep the clock around and a myopia which makes him wear specs off screen and sometimes turns his pink cheeks red. The other night, roaming around without his glasses at a party of old friends, Bob was muttering, “Nice to see you again—haven’t seen you for a long time,” to one and all.

“Yes, you jerk,” said Don Oreck. “It is nice to see you again, isn’t it? Remember me? I only brought you here!”

But sometimes even short-sightedness can be a help in the longer race. Especially if, like Bob, you get the habit of looking hard at what’s close at hand, learn it well, and don’t knock yourself out fretting about the future. Usually, in Hollywood or anywhere else, the future takes care of itself. The big break comes along if you rate it. At least that’s how things worked out for Robert Charles Francis.

THE END

—BY KIRTLEY BASKETTE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954