Man, That Mineo’s The Most!

“Fantastic!”

Sal Mineo doesn’t know how else to describe it. He was thinking of that night in 1955, when he happened to be driving about Hollywood in his ’49 Mercury. Passing the Pantages Theatre, he noticed the crowds outside and the celebrities pulling up in their Cadillacs. Then he realized—it must be the night of the Academy Awards. He wasn’t sure what the Awards were. He only knew you needed a gilt pasteboard ticket to get past the doors, and he didn’t have one.

“I remember wondering what it would be like,” Sal recalls, “to be in there—to be one of them.”

And then, one year later, the fantastic thing happened. Last March, Sal was not only one of the lucky ones with a gilt pasteboard ticket, he was right up there on the stage itself. For his performance as James Dean’s sidekick in “Rebel Without a Cause,” the seventeen-year-old actor had been nominated for best male supporting actor.

AUDIO BOOK

“I didn’t get an Oscar,” Sal points out, “but I did get a giraffe. I keep it in my car.” Then, suddenly aware of lifted eyebrows, he explains: “It’s a toy giraffe. Some girl sent it as a consolation prize.”

As Sal describes the big night, however, he scarcely sounds in need of consolation.

“It’s a lucky thing I didn’t win,” he confesses. “It was such a relief when Jack Lemmon got it. The whole month before, I was in a daze. I didn’t know exactly what the Awards were or what they meant. All I knew was—they were important. Back home, my sister, Sarina, had a place all saved for my Oscar. ‘Don’t put your heart on it,’ I warned her. Then, it got so I couldn’t write home at all.

“I took my mother to the Awards,” he continues. “People kept asking: ‘Who’s your date?’ And when I told them, ‘My mother,’ they all thought this was the most wonderful thing.” Sal shakes his head, still amazed by the whole affair. “Mother was so excited, I thought any minute she would cry. Then afterwards, when I didn’t get it, each of us thought the other needed comforting. I didn’t mind for myself—I just thought she did. And Mother didn’t mind for herself—she thought I did. But then people started coming up and congratulating us. They said it was an honor just being nominated. ‘Look forward to the next movie,’ they told me. ‘That’s the important thing.’ ”

Back home, however, Sal’s sister was not so philosophical about it. “What do they know in Hollywood?” Sarina said.

In Hollywood, all they know is that Sal Mineo is one of the nicest, most refreshing kids ever to hit the film colony. With six big pictures to his credit and everyone “looking forward to his next movie,” he is still as modest and unspoiled as the day he arrived.

It’s no accident, either. “I’m never going to let this business change me,” Sal insists. “I’m never—you know the old saying—‘going Hollywood.’ ”

And as he talks about himself—-tells something about his life before breaking into pictures—it’s not hard to understand why. Sal will never “go Hollywood” for the simple reason that he’s too “gone” on the Bronx. That’s his real home, the Bronx section of New York. And the big thing around the Mineo household isn’t Sal’s film career—it’s caskets!

“Yes, my father’s a casket-maker.” Sal says it dead-pan, then steals a sidelong glance to watch the effect on his audience. Apparently, it’s always effective, and he can’t keep from smiling. “Oh, we don’t have anything to do with the bodies or anything,” he adds quickly. “We just make and sell caskets.”

The important point is the we, for the Universal Casket Company has always been a family business. But then, anything that happens to any one of the Mineos is family business. They live together, they work together. And anything they have, they share together. Critics who have been amazed at Sal’s acting, wondering where he gets a perception so far beyond his years, can find the answer right in the Bronx. For the Mineos are real people, and the thing they have most of—the thing they share so freely with each other—is life itself.

Salvatore Mineo is not only Sal’s real name, it’s his father’s, too.

“My father was born in Sicily,” Sal says, launching into the family history like someone telling his favorite story. “He used to carve miniature animals in ivory and wood. That’s a big business in Italy, but not in America. He came here when he was sixteen and, for two years, he could only get odd jobs, doing all kinds of dirty work.

“Then he met my mother. She was born in New York of Neapolitan parentage. He tried to date her, but she wouldn’t go out with him—not unless he could speak English. When my father finally took her out, she was amazed at how quickly he had learned the language. ‘Here’s a guy with ambition,’ she felt.”

She not only married him, she helped him realize these ambitions. It was Josephine Mineo’s suggestion that her husband go into cabinet-making. She was the one who gave him the courage to turn down a tempting offer with a furniture company and hold out till he got the right job, with the Bronx Casket Company.

“My father was so good,” Sal says proudly, “they made him a foreman. Only, it wasn’t the usual foreman’s job, just overseeing others. My father worked like a dog—even nights. It was my mother, though, who really made him. ‘Here you are,’ she told him, ‘working like a dog for others. You should be working for yourself, and for your children.’

“My father didn’t have a dime,” Sal continues, “but friends insisted on putting up the money to back him. So he went into business with my uncle.”

Today, the Universal Casket Company consists of two buildings, one a factory, the other a casket showroom. And all those friends who put up money have long since been paid back. But Sal can still remember what it was like for his father in those early days.

“The first five years were the toughest,” he recalls. “I never saw a man age so fast. He and my uncle used to do all the work themselves—hauling lumber, making the caskets, painting them, even delivering them. My mother used to go down every day. And, as soon as they were big enough, my two older brothers, Mike and Victor, worked at the company.”

Sal had to stay home. His job was baby-sitting for Sarina, his younger sister.

“I guess that’s why I’m so close to her,” he says. “I took care of her—everything from feeding to good-night stories. Sure, I wanted to be out playing with the other kids, but we all had to help out.”

Nevertheless, he managed to get in his share of swimming and baseball. “Like every other kid,” he confesses, “I wanted to grow up to be Phil Rizzuto.”

And even watching Sarina was fun. “Every weekend,” he recalls, “I used to get a salary of fifty cents. You know what I’d do with it? I’d go down to the candy store and get some soda, ice cream and jelly beans. Then I’d go home and we’d have a party—Sarina and I, and our two cats, Smoky and Tiger.”

Somehow, although “they were broke and every cent had to go into the business,” Mr. and Mrs. Mineo managed to see that none of their children ever wanted for anything, “even if they had to deprive themselves.” And all of their sons received exactly the same treatment. When one of the boys wanted a bike, all three got them. Today, Sal still can’t figure , out how his parents managed it, but when he needed money to start his career—somehow, they raised it. And, somehow, they raised the money that enabled all their children to get the education they themselves could never afford.

“I’ve been a roving man,” Sal declares, referring to the number of schools he went to. In the Bronx, he attended St. Mary’s, Holy Family, and Public School 72. After going on the stage, he went to the Lodge Private School for young professionals.

“I had a lot of ambition to do something,” Sal remembers, “but I didn’t know just what.” His brothers Mike and Victor knew that they wanted to study business administration in college, so they could help expand the Universal Casket Company. Even Sarina knew that she wanted to be her father’s private secretary. Only Sal was uncertain. He knew he had a talent—but what was it?

He was eleven when he found out. An agent for Cheryl Crawford, the Broadway producer noticed him in a dancing class because “he looks Italian.” Sal was taken to an audition, along with fifteen other I boys, and asked to say: “The goat is in the yard.” He said it, and the next thing he knew, he was in Chicago—playing Salvatore in the stage version of “The Rose Tattoo.”

After the Tennessee Williams’ play, Sal did some summer stock. Then Oscar Hammarstein signed him to understudy the role of the crown prince in the Broadway musical, “The King and I.” When the boy who originated the part outgrew it, Sal took over and played it for a year.

Sal’s first film was “Six Bridges to Cross,” in which he played Tony Curtis as a boy. It was a good start, and Sal began receiving offers to do bit parts. Mrs Mineo advised him to turn them down, just as she had once advised his father to hold out for the right job. It was a big gamble, but “if you don’t get good parts,” she said, “I’d rather see you home.”

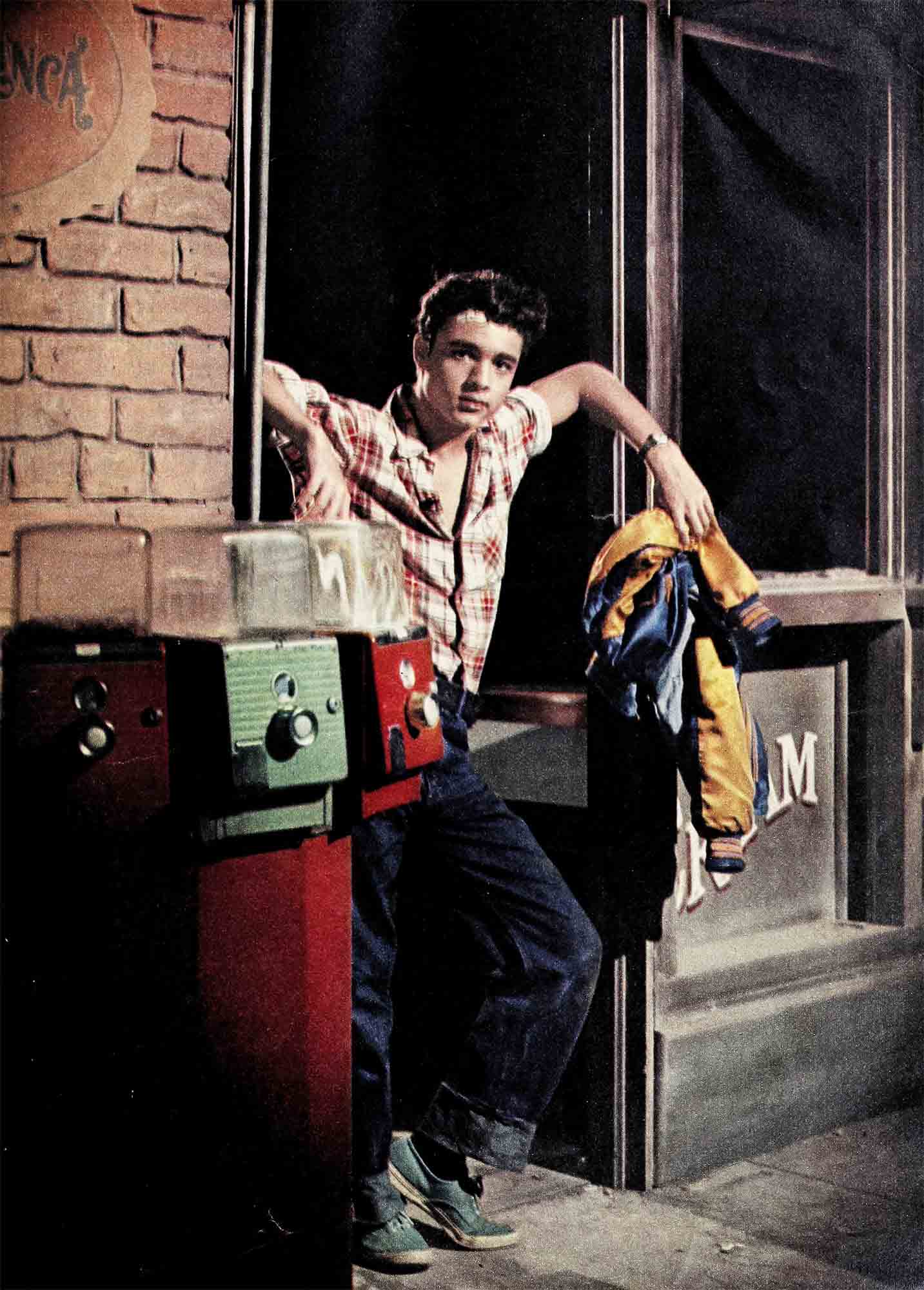

The gamble paid off. Sal has gotten good parts—in “The Private War of Major Benson,” “Rebel Without a Cause,” “Giant,” “Crime in the Streets,” and finally, as Rocky Graziano’s pal in “Somebody Up There Likes Me.”

“Rebel Without a Cause” is Sal’s favorite picture. “It wasn’t just the part,” he says, it was the people I worked with.” But he is proudest of his role as Angel Obregon III, in “Giant,” the George Stevens production of Edna Ferber’s novel. “I was only sixteen when I made the picture but they had me playing an eighteen-year-old.” He was also old enough to try playing angles.

“In the picture,” he recalls, “I’m a Mexican. I go off to war, a soldier, and then I come back a hero—in a casket.” Naturally, but to no avail, Sal tried to talk Warners into using a Universal Casket.

What with all this picture-making, Sal spends more time on the West Coast than the East. He still thinks of the Bronx as home, however, and the trip to Hollywood as just commuting.

Which reminds him: “Some people think it’s unbelievable. They’re surprised that I still live in the Bronx. They expect me to live in Manhattan. And they’re stunned when they still see me riding around in a ’49 Mercury instead of a Cadillac. Even out in Hollywood, they can’t understand why I live with a private family instead of in a big hotel or apartment house.”

In Hollywood, Sal has a resident guardian; he is B. H. Hoene, an instructor in the Pullman Company.

“He has a wonderful family,” Sal says. “I get rid of all my corny jokes on them. Every day, once I’m through at the studio, that’s where I go. They’ve a son and daughter, eighteen and nineteen, and I go out with their friends, not just with the show business crowd.”

As for his car, Sal’s very proud of it, having worked on it himself.

“I got a week and a half off in between pictures,” he recalls, “and I got a bug. I took my old car and stripped all the chrome off—this way it’s a custom job—then I added rear radio antennas, hoods over the headlights, tail lights, and put skirts on it.” He even took off the letters of the make, plugged up the hole, and substituted his own brand name—Rum-Crier! “Then I had it painted a wild color—midnight blue,”

He looks at you frankly. “Crazy?” he asks. But Sal doesn’t mean crazy-wild, for he’s not out to break any speed records. In fact, he’s an honorary member of the Kirb Krushers, a car club that throws you out if you so much as get a ticket.” When it comes to driving, Sal only has one ambition.

“At the next big premiere,” he says, “you know what I’d like to do? Instead of driving up in a studio Cadillac, I’d like to drive up in a hot rod.” Delighted with the idea, he tries to make you visualize it as clearly as he does. Imitating a loudspeaker, he announces: “Here we have Mr. Mineo’s car.” Then he makes like a crazy, souped-up automobile horn. Laughing, he can’t help sighing, “Oh, it’s a lot of fun!”

But then, everything is a lot of fun for Sal. I get a kick out of going to drive-ins—all kinds. I like bowling and pool. No, you better make that billiards; people might not understand. I don’t play pool in pool halls. As for baseball, I guess I grew out of it. Now it’s water-skiing. I can spend four or five hours at it. When I’m through I can’t walk. And yet, I have a ball.”

Sal’s enthusiasm for water-skiing dates back to his Broadway days, when he was playing in “The King and I.” Yul Brynner, who played the king, rented a home in Connecticut, on Long Island sound, and Sal used to visit him every weekend.

“He showed me the basic principles of water-skiing right on the pier,” Sal recalls, “then told me to get on skis. When he saw how much I liked it, he gave me a pair of my own.” Sal remembers returning home with the skis and crying out: “Look, Ma, now we have to get a boat!”

But Yul Brynner, who plays another king in Cecil B. DeMille’s forthcoming “The Ten Commandments,” also inspired Sal with another of his enthusiasms—directing.

“Here he was,” Sal says, “the star of the biggest musical on Broadway, and he was directing television shows on the side. In fact, he directed me in my first lead on television, in an Omnibus show.”

Thus, while everything is “a ball” to Sal, he has his serious side, too. “First, I want to be a good actor,” he insists. “And then, if I’m good enough, maybe people will give me the opportunity to direct.”

He also has two other ambitions. One is to go to college to study play wrighting and directing and also “meet thousands of kids out of the business. I like to be with a regular bunch and sort of live my own life.” The other ambition is to gain weight.

“I saw a kinescope of myself,” he confesses. “My head and face were older than my body. I figure if I can put on fifteen pounds, then maybe I can play in an Indian movie—or do one of those Sabu things. I’ve started a campaign I’m now drinking ginger ale mixed with cream. That’s supposed to put flab on, you know. I hope to go from 121 to 138 pounds.”

Whenever he is home, Sal eats “all the i spaghetti and fattening Italian foods” his mother can cook. The only mystery is when does she get the time? For Josephine Mineo, like the rest of the family, is doing all she can to help Sal go further in his career.

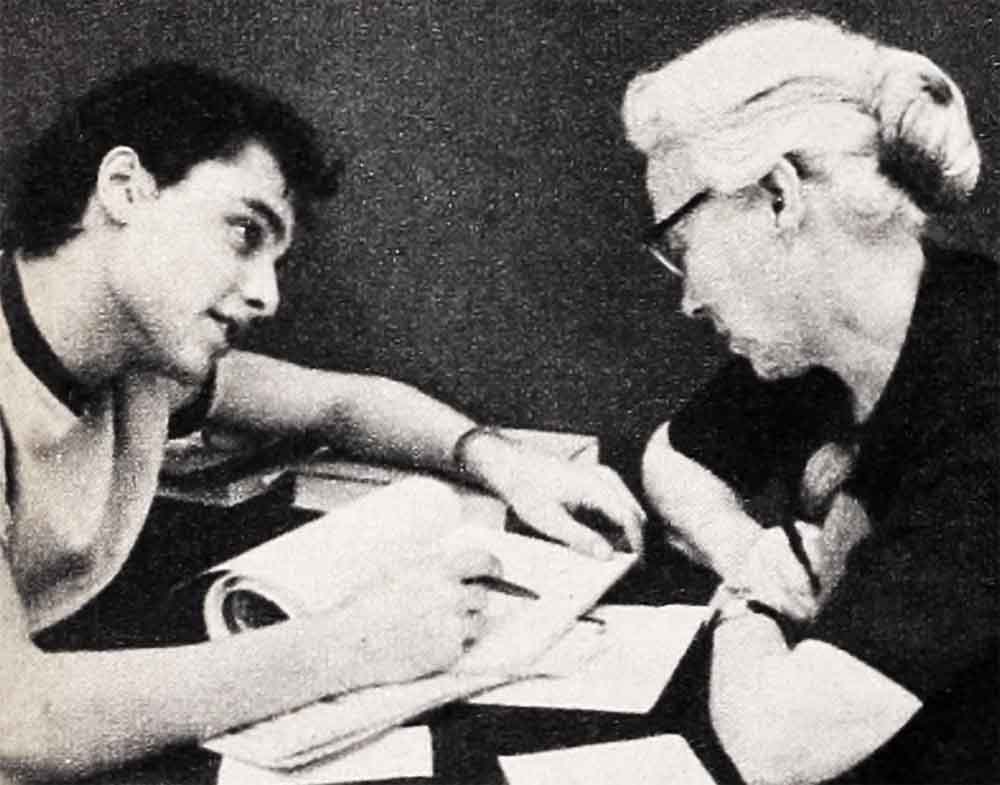

“I’d be lost without them,” he admits “There are a lot of things I can’t handle My schedule, for one thing Mother keeps it for me, handing me a list each day ‘This is what you’re to do tomorrow,’ she says.”

In order to make out that list, however, and keep it as short as possible, Mrs Mineo has to spend most of the day by the telephone, evaluating all the calls that come in. Not all of the phone calls are business. Many are fans asking to speak to Sal. But there are as many adults among the fans as teenagers. They feel that Sal is like their own son. And Mrs. Mineo, understanding this, hasn’t the heart to change the phone number. These are the people who have helped make he son a success, and she feels as responsible to them as Sal does.

He has had to hire two secretaries just to handle the requests for photographs. This, too, is a family enterprise, with his two older brothers helping him pack the photographs in cartons, loading them in a car, and driving them down to the post office. And then there’s the fan mail.

“I like to read every letter.” Sal says. “And I try to answer them all.”

But the one who has been affected most by Sal’s success is his sister, Sarina. Suddenly, she has found herself surrounded by more girlfriends than she knows what to do with. By some coincidence, they seem to prefer visiting her when Sal is in town. And sometimes when the pressure becomes too great, she has to produce her famous brother at parties. At such times, the girls are allowed to look—but they mustn’t touch. Sarina’s brothers sometimes wonder why she just doesn’t charge admission.

But, although the Mineos all help one another, there’s one thing Sal must handle alone—and that’s “his women.” When he arrives at the airport, for instance, there’ is invariably a crowd of girls waiting. Each one wants a handkerchief or some article of clothing. And Sal is well aware from his own experience, that “if I give a hanky to one girl, it isn’t fair to the others, and pretty soon I’d have no clothes on at all.”

Then there’s that girl in the Bronx who wants Sal to take her to a prom. “I wouldn’t mind,” Sal admits, a bit wist fully. “In fact, I’d like to. Only, it wouldn’t be fair to the other girls.”

If his brothers Mike and Victor groan inwardly at this, it’s because they know Sal is making it twice as hard on himself. It’s hard enough being “fair” with one worn an, let alone hundreds. But they agree with their kid brother. “It’s fantastic!” They don’t know how else to describe it.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments