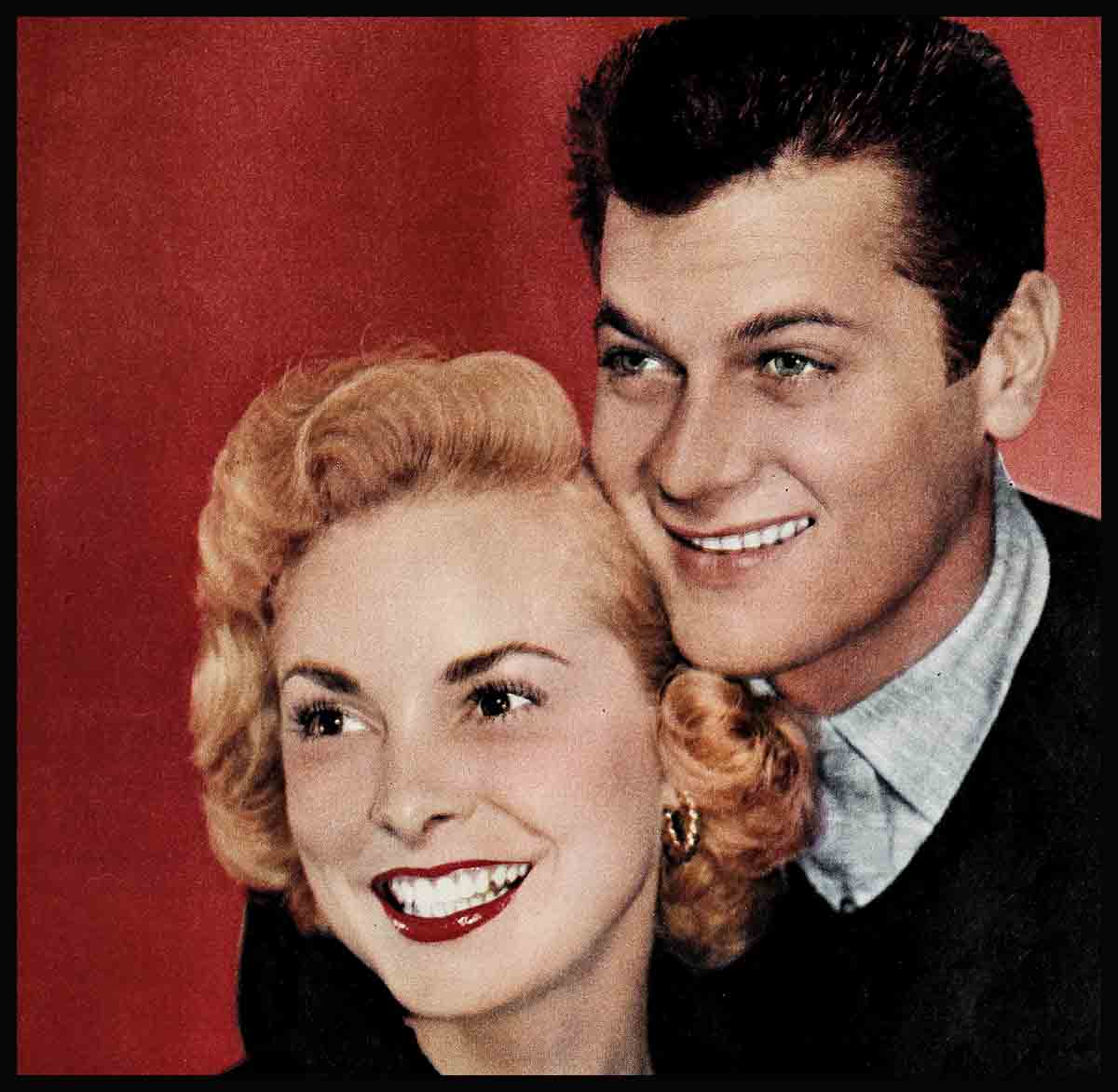

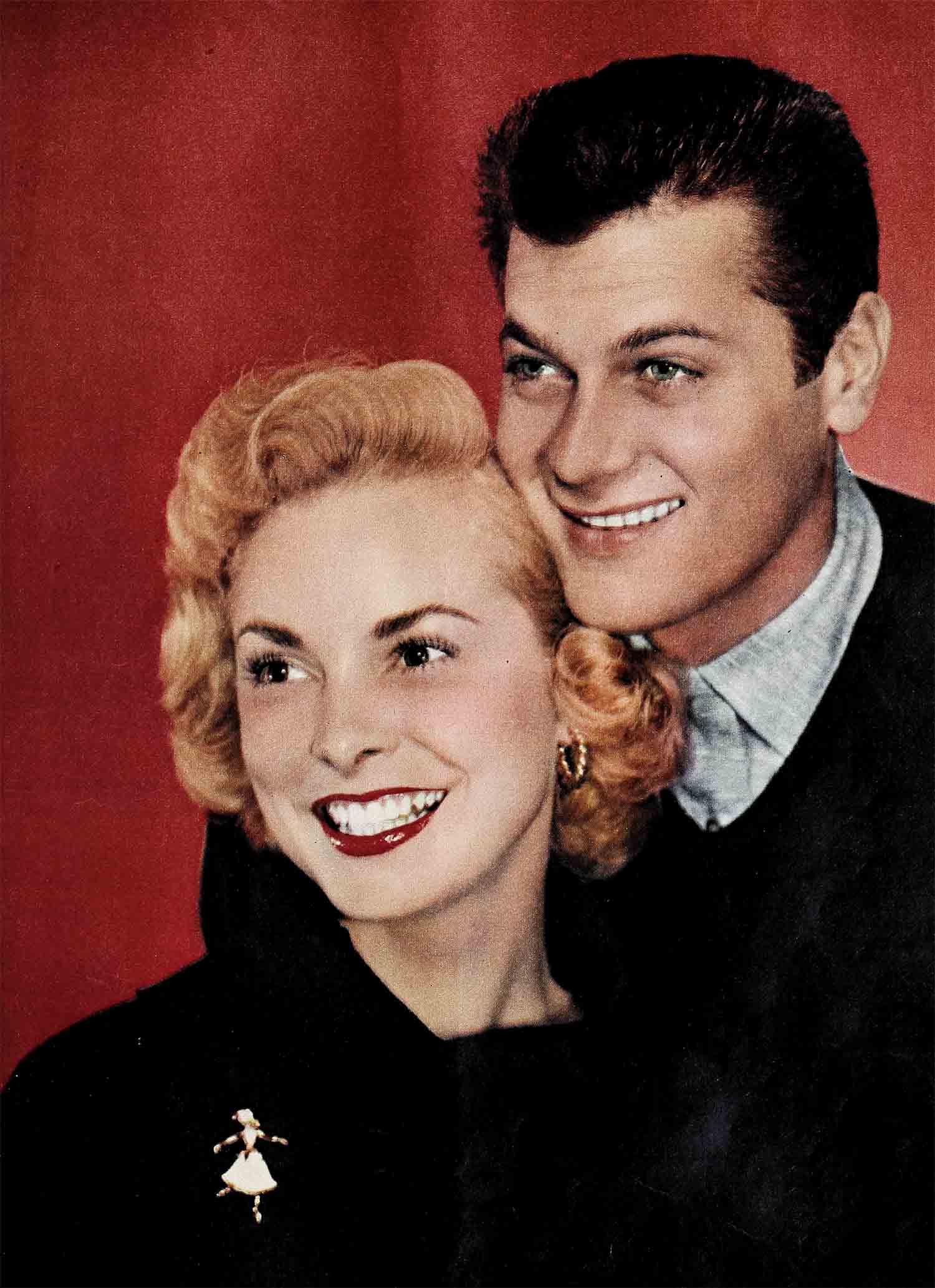

No Sad Songs—Janet Leigh & Tony Curtis

“It would have thrown me for a loop,” Janet Leigh says about the expected baby she lost—the baby she and Tony Curtis had hoped for so earnestly and long—“I would just have curled up and died except that Tony was so absolutely wonderful about it.”

The long letter he wrote her from Hawaii, where he was on location with the “Beachhead” company, the night he heard the sad news from Janet’s mother via trans-Pacific phone, was, Janet says, “the kindest, most understanding, most wonderful letter I have ever received.”

Tony had phoned her the night before, on July 6, her twenty-sixth birthday.

“How are you?” were his first words, and he sounded concerned even though she had assured him every time they had talked since she left him in Honolulu to fly back to California, and to work in “Prince Valiant,” that everything was going normally and well.

“I’m fine,” she told him again, “just fine,” trying to voice as much conviction as she had earlier when Tony had phoned, but trying against odds this time. She was fibbing—just a little. She didn’t feel well, really. She hadn’t been sleeping, she felt strangely queazy and “very un-hungry,” and birthday or no birthday, she felt upset and lonely, not like herself at all.

She blamed it all on the loneliness. Not that she and Tony had never been separated before. “Separations,” she will tell you ruefully, “have been the story of our married life.”

But now, with the baby coming, with so much to talk about, so much to plan and share, it seemed wrong that they couldn’t be together. Before he hung up, Tony reiterated the earnest advice he had given her just before they said their farewells—only six days earlier, that had been, and it seemed an eternity—in their hotel suite at the Royal Hawaiian.

She must rest. She must take really good care of herself. She must take it easy.

“Because,” he told her again, “we have more to think about now than just ourselves. We have to think about the baby.”

Janet promised to be good. And she had been good, she really had. She had turned down all sorts of gay invitations, rested at the apartment, and at her mother’s, relaxed determinedly while waiting for her picture to start.

She would take it easy. And Tony, she told him before they hung up, must keep his promise too—to telephone every other night, not every night. There was the budget to think about, now that the Curtises soon would be three.

And Tony promised. But he didn’t keep his promise.

The very next night he placed a call to their home number, just at the time, strangely, that Janet was being admitted to St. John’s Hospital for emergency surgery.

“I just had a premonition,” he said later, “that something had gone wrong.”

When he couldn’t get an answer at their apartment he called his mother. She had talked with Janet earlier in the day, and everything had been all right then. But Janet had told her, too, that she would be home that evening. At this, Tony called Janet’s mother, who had just come in from the hospital. The doctor had told her that everything was all over. There would be no baby—not this time. But Janet would be fine. She broke the news to Tony, as gently as she could.

It was then that Tony sat down and wrote the letter.

He was terribly, terribly sorry, he said, because he knew how disappointed Janet would be.

(“I would be disappointed,” Janet thought as she read. It was Tony’s hurt she was worrying about; he loved children so, and had been beside himself with happiness when they thought they were to have a baby of their own.)

But she was not to worry. After all, she was the one who mattered. It was her health that was really important.

And they were still young. They would have lots of babies. Four babies. Twins!

There was more, lots more, but words written for Janet’s eyes alone.

Janet says she will always keep that letter, to remind her how close two people can be, especially when they are in trouble.

After the joyous three weeks they had just spent together, trouble came like a stranger to these two.

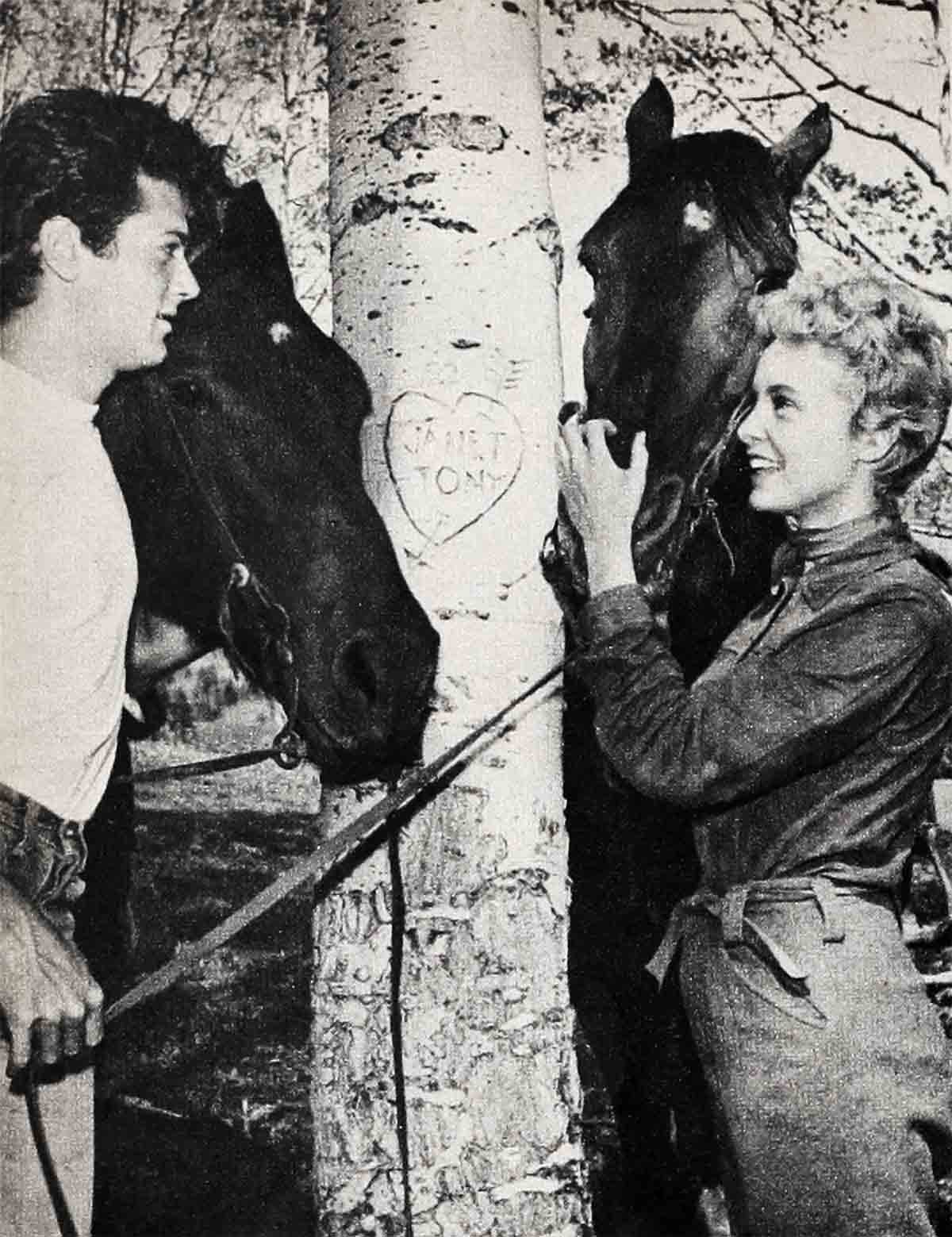

Their trip to Honolulu, agreed to on a wild impulse at the very last minute had been the most exciting few days they could remember, a real second honeymoon. Last year Tony went on suspension to be with Janet in Colorado where she had been at work on a picture.

They had had their vacation, six days in Las Vegas, three weeks in New York—more time off from work than they had had together since they were married. (“It was the vacation that did it,” Janet had gurgled when she first learned that a baby was on the way.)

Tony had to go to the islands for “Beachhead” and was upset. He hates flying, but didn’t want to leave Janet a minute earlier than was necessary, especially since there was a possibility, just the barest possibility so far, that she was pregnant.

“Take the boat and if the studio will let me have the time, I’ll go with you,” Janet said impulsively.

They would have five relaxing, sunbaked days on the boat. It wouldn’t matter if she had to turn right around and fly back to work the minute the Lurline docked. It would be worth it, just for the boat trip.

“Crazy!” Tony said, but set about getting reservations as soon as Janet’s agent said she was clear.

The next few days were a madhouse. Getting reservations so late proved an almost impossible hurdle. They actually went abroad with Janet booked into a single cabin on A-deck, Tony sharing a double on D-deck with a more foresighted passenger. The D-deck roommate was only too happy to trade for Janet’s airier, flossier quarters, however.

Also, at the last minute, Tony insisted that Janet have a pregnancy test. He wanted to be sure. Janet thought it was too early to tell, but had the frog test anyhow. The results, she was told, would not be available for several days. They wouldn’t know, they thought, until Janet got back to California. She gave the laboratory her maiden name, Jeannette Morrison, just in case. She didn’t want any publicity.

But somehow the positive results of the frog test leaked out. “I guess,” Tony muttered when Janet’s studio, her agents, and twelve dozen columnists began bombarding the Lurline with frantic queries about her pregnancy, “we got a talkative frog.”

“Can’t even think things anymore,” was Janet’s reaction, and she felt just a little bit cheated. Every woman should have the privilege, she thinks, of doing her own announcing about anything as important as her first child.

But once the first flurry was past, they were happy and relaxed, swimming every day in the Lurline’s swimming pool, gossiping with their good friends, the Van Johnsons, who also were aboard, making wonderful new friends, going to the movies on shipboard to see “The Naked Spur.”

“They gave me top billing over Jimmy Stewart,” Janet says. She didn’t know whether to be flattered or embarrassed.

The docking in Honolulu, a three-hour frenzy starting at 5:00 A.M., was, Janet says, “like New Year’s Eve at eight o’clock in the morning.”

The Kayaks and the catamarans coming to meet them, the divers the singing and shouting, and then, when the press boat came alongside, the kisses and alohas and the leis—so many leis Janet barely could see over the fragrant mass of them. And then ashore, where they could barely fight their way to the hotel car for the hundreds of fans who had heard of their arrival and come out to meet them. Both Janet and Tony (and Janet says Tony is not a sentimentalist, as she is) found themselves fighting back tears of happiness.

“It’s so wonderful,” Janet says, “to go someplace you’ve never been before and find that you have friends there.”

They loved every minute of their six days on the Island. Janet was on twenty-four-hour call, but “the studio had a heart” and left her in peace. Tony turned into “a bronze giant.” Janet—who had promised to stay fair for her picture—lolled under a protective umbrella and admired her husband’s tan. Thinking about the baby, blushing a little when their newly made friends kidded Tony about his coming fatherhood, added up to perfect happiness.

It was midnight when Janet Leigh boarded the Pan American flagship at Honolulu airport to speed back home and to start work on “Prince Valiant.”

A host of friends came to see her off, both old friends like the Van Johnsons (Janet made her first picture with Van and ever since he’s been “sort of a guardian angel”) and new friends she and Tony had made throughout the six exciting days they had been able to spend together at the Royal Hawaiian.

Despite the gay farewells, the kisses and the alohas, and the leis, she felt lonely, lonelier than she had ever felt in her life. Because Tony wasn’t there. He had left a few hours earlier for the neighboring island of Iloilo to join the location company gathering for the start of his picture “Beachhead.”

They had said their goodbyes alone in their hotel suite. Tony has always hated public farewells, and this time he particularly wanted Janet to himself. The things he wanted to say were for her ears alone.

She must rest. She must take really good care of herself. She must take it easy. He knew it would be hard for Janet who normally is about as passive as a cage full of happy squirrels, but she must.

“Because,” he told her, looking hard into her wide grey eyes, “we have more to think about now than just us. We have to think about the baby.”

Janet was remembering this moment when she snuggled down in her seat on the big plane, the sense of aloneness crowding in on her again. It was new and strange, this loneliness. It wasn’t as though she and Tony had never been separated.

“Separations,” she says ruefully, “have practically been the story of our life.” Even in the first weeks of their marriage they were three thousand miles apart, Janet working on a picture in Hollywood, Tony touring in the East.

But this was different. There was something newly deep and mysterious pulling them together now, something new and important to share.

And in the days that followed, with Tony’s phone calls and with his wonderful letter after their heartbreak, Janet realized that even though separated by distance, she and Tony were closer together than ever.

The words in his letter were true. They will be just as happy again, these two. For they will be together, and tomorrow is another day.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953