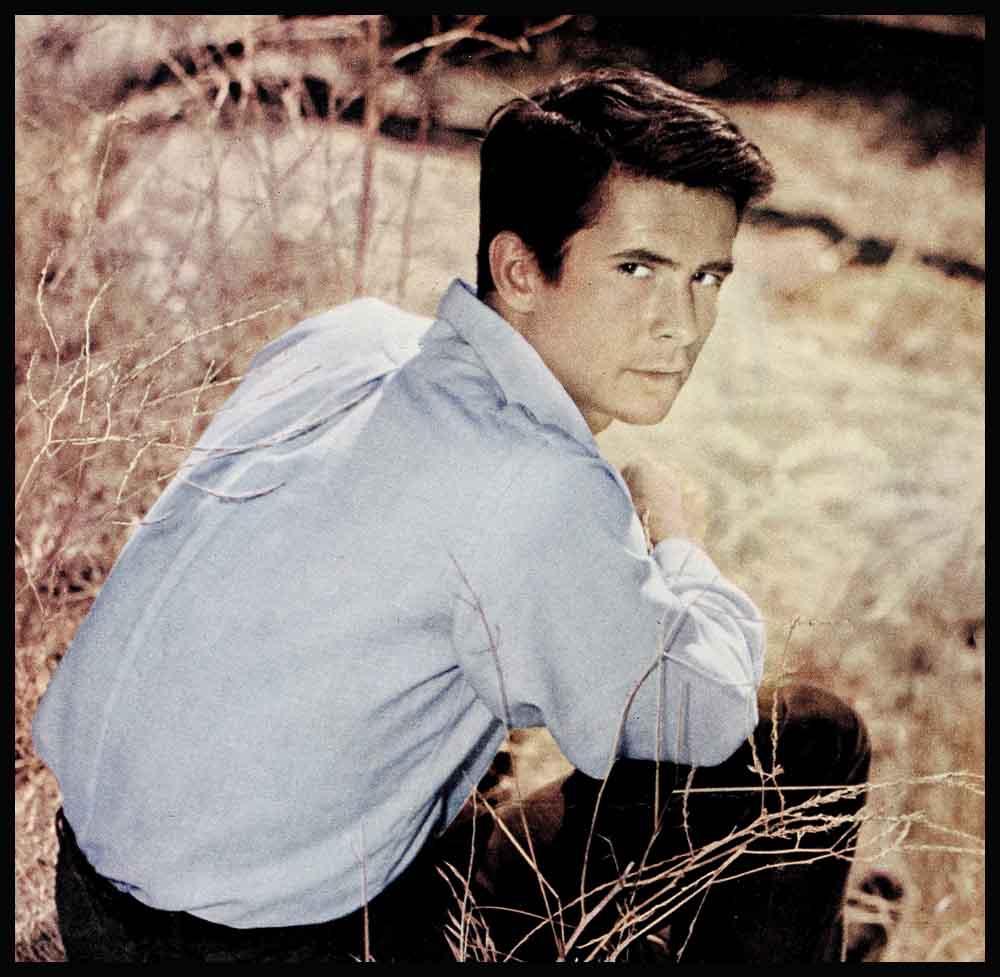

Barefoot Boy With Cheek?

It was a rainy day in Boston. A young boy, tall, slim and spectacled, picked his way carefully along the slippery sidewalks. He was hunched in a trench coat buttoned high at the collar. His hands were in the coat pockets, which was not unusual—except that the right hand was caressing the butt of a revolver.

The boy was Tony Perkins, and at the time he was imagining himself a famous private eye on the trail of a criminal. The gun, purchased from a friend on installments from Tony’s allowance, gave just the right touch of drama, heroism and illicit adventure to the occasion.

Now let’s fade out and fade in ten years later. The same boy, taller but still hunched and boyish, on the set of “The Tin Star,” at the Paramount studio in Hollywood, is wearing two guns slung from his hips. At a command he draws them both with split-second precision.

The instructor comments, “Wonderful, Tony, that’s about as fast as I have seen it done.” The words reach Tony but fail to register, because in his imagination he is once again the hero about to do battle with the forces of evil.

Though the young boy has grown into a man now, he still lives partly in his imagination. As a youngster in Boston, from a better than ordinary social and economic background, Tony Perkins fashioned for himself a romantic world to liven an otherwise well-regulated existence. As a film star he is still playing the same game.

AUDIO BOOK

Because he is really what he seems to be—a nice enough, ordinary young fellow—and because he feels that as an actor he should be more colorful, Tony has been working overtime at it.

Sometimes his attempts at achieving color border on the ridiculous. During the filming of “Friendly Persuasion” he used to eat regularly at Googie’s, a small coffee shop next door to Schwab’s in Hollywood He told new acquaintances there that he worked in an airplane factory. “I thought they’d like me better if they didn’t think I was another actor in competition with them,” he says by way of explanation.

More likely, Tony hoped that when they did learn he was starring in a big film, they would be amazed at his modesty. He was also hoping that the discovery of who he really was would have some dramatic impact.

Tony was playing a game much as Jimmy Dean did the day he drove up to the “Giant” location in Marfa, Texas. Finding a new gateman on the job, Dean tried to get in without announcing himself as a star of the film. In blue jeans and leather jacket, with his old junk car, Jimmy hardly looked like an actor, and he knew it.

But he wanted to test the policeman to see if the man knew who he was; just as Tony was probably testing the new acquaintances to see if they had heard of him.

Much of Tony’s eccentric behavior is likened to Jimmy’s and is equally studied. For example, Tony is reported to have walked out of his apartment many times barefoot, supposedly having forgotten to put on his shoes.

Unquestionably, it must take a certain amount of cheek to carry off this kind of activity. In Tony’s case, however, much of the odd behavior is reported rather than seen. And the reporter is invariably Tony, who tells interviewers how he walked out of the house barefoot.

To a large extent these stories have been successful, but a few have backfired. For example, in a recent Life magazine story, much was made of the fact that Tony hitchhiked daily to Paramount Studios from his apartment, and that he cooked his meals on a hot plate in his room. As a matter of fact, he may have hitchhiked to Paramount once for the record, but it’s certain that he didn’t do it as a daily habit. As for cooking in his room, the management at Tony’s apartment was miffed at the story because cooking in nonhousekeeping rooms is frowned upon. When they were told that it was all for publicity, no serious damage was sustained.

Some of the stories have the ring of familiarity. Tony once said he would “rather be called a ‘young’ anything than ‘another young’ anything.” Marlon Brando said it earlier, and the late Humphrey Bogart said it before Marlon.

Sometimes it’s not that Tony tells deliberate untruths about himself, but that he allows you to assume things. He cleverly throws out the bait, the listener nibble, and then plays out the line. Here’s a for-instance: During a recent interview Tony said something about going on his bike to a party. The interviewer knew that Tony had a date, so he asked if she was on the bike, too. Tony’s answer was merely a smile. The reporter assumed that the girl went on the bike— which she didn’t—but the story spread.

To an interviewer Tony has a chameleon-like quality, changing protective coloration to accommodate the questions. He can shift easily from shy ingenuousness to long thoughtful silences broken by terse phrases or half sentences. With his head lowered he will look up at you, a perplexing, reflective look on his face. You want to know everything about him; you sense the shifting emotions, the racing and twisting thoughts. Although you often suspect that he is telling a half-truth or acting boastfully modest, you go along with him because, in a word, Tony has charm.

Everyone who comes in contact with Tony is aware of this charm, including the housekeeper at the Chateau Marmont where he now lives. Norma Moore, one of Tony’s Hollywood dates, considers him one of the most charming men she has ever met—and one of the most unpredictable. The charm which he turns on and off at will enables him to keep his head above the flood of stories which he has caused to circulate about himself.

One day while I was talking with Tony at Paramount, Autumn Russell, a very pretty contract player, joined us. The change in Tony was remarkable. It was almost as though someone had told him that the cameras were grinding, and he suddenly flashed charm from every pore. His stories became more elaborate. His own importance in them increased. He was doing as any man would—trying to impress a pretty girl.

But, more important, Tony knew Autumn was married, so he had no intention of asking her for a date. Yet she represented an interested audience. Like many young actors, Tony only needs one other person and he’s on-stage. If the other person happens to be a pretty female, so much the better.

With all this, Tony can be far more businesslike in an interview than stars many years his senior. During a talk with me for this story, he asked if I had brought a tape recorder along. When I said no, he seemed disappointed. I asked why.

“With a tape recorder there would be no chance of being misquoted,” he said.

I explained that I was going to take comprehensive notes. He seemed pleased. “I get nervous when people don’t take notes,” he said.

The interview was conducted at Lucey’s restaurant across the Street from Paramount. Tony, who doesn’t drink or smoke, ordered a light supper and told me how he came to be an actor.

He was born twenty-four years ago on Twenty-Third Street in New York. His father was Osgood Perkins, a matinee idol of the Twenties; his mother was a Wellesley College graduate and a socialite. The Perkins had been married ten years before Tony was born. He was their only child.

Osgood Perkins died when Tony was five, and Tony says he has no memories of him. Following her husband’s death Tony’s mother moved with him to Brook-line, Massachusetts.

Until this time, Tony spoke mostly French as he had been raised by a French governess.

As a child Tony was considered something of a hell-raiser. He fought a lot with other children. His favorite game was to stuff an old suit of clothes with rags and blankets and throw it in front of passing cars. “I was threatened with reform school many times as a kid,” Tony recalls with satisfaction. “I guess it’s a miracle never got in real trouble.”

Tony’s first ambition was to be a lifeguard, followed by an overwhelming wish to be an actor. Perhaps hours spent probing over his father’s old scrapbooks had something to do with that. In high school Tony appeared in all of the school plays.

Since Osgood Perkins had gone to Harvard, Tony was enrolled at Browne and Nichols, a preparatory school for Harvard. He did not cause much of a flurry in academic circles. In fact, the only high school subject in which Tony excelled was French, which he spoke fluently, thanks to his childhood training. But he kept his knowledge of the language a secret and progressed normally with his class “That way I was sure of good grades in at least one subject,” he recalled.

“Schoolteachers,” he added with a grin, “like to think I’m a boy who needs mothering. That’s how I got through high school, and I guess that’s my appeal now to moviegoers.”

His appeal to moviegoers is certainly a strong one, maternal or otherwise. But if playing the little boy was enough to get Tony through school, it was not enough, apparently, to get him into college. He was the first student in the history of Browne and Nichols who was not allowed to take the Harvard entrance examinations because his marks were so low.

After leaving prep school he took odd courses, did summer stock (including “Years Ago,” a Ruth Gordon play) and passed some time at Rollins College in Florida. Eventually he wound up in New York’s Columbia University taking extension courses.

It was during his stay at Columbia that Tony heard M-G-M had bought “Years Ago” and planned to film it under the title, “The Actress.” On a hunch he hitchhiked to the coast and said he’d like to test for the part.

He was signed. After five weeks “The Actress” was finished and Tony went back to New York. He made sure he was in New York when the picture was released. But no one seemed impressed with it.

Then Tony went for an interview with Otto Preminger for the part of Joseph, opposite Rita Hayworth, in Columbia’s “Joseph and His Brethren.” He didn’t make it. Mr. Preminger took one look at him and said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Perkins, you won’t do. We’re looking for Old Testament faces. You have a New Testament face.”

With his New Testament face Tony went to see Elia Kazan for the lead in “East of Eden.” He ended up with a Broadway role in “Tea and Sympathy.”

“I almost didn’t take the ‘Tea’ part because I didn’t think I was good enough to do it,” Tony recalled. “But then I figured that if Kazan thought I was good enough, I must be.”

Later in the interview, Tony told me that he had expected to get the “Tea” role because he was “equipped to play it.”

“My success has been a sort of chain reaction,” he said. “It started with summer stock, then ‘Years Ago,’ the film and some good TV parts. Then came ‘Friendly Persuasion.’ I haven’t been out of work for more than a week in years. I guess you might say I’ve been uncommonly lucky.”

One might also say that Tony has been uncommonly smart. He knows exactly where he is going and how he is going to get there. He’s far more sensible than most other actors his age, and he has very few illusions about his own possibilities or Hollywood’s.

During the filming of “Friendly Persuasion” he spent hours studying Gary Cooper’s every move and gesture so that his role as Coop’s son would be even more convincing. He was also studying Coop to see what made him such a great actor. “I learned another side of being professional,” Tony admitted. “Coop makes acting appear easy, and that’s part of his charm. The truth is he works hard at it. I learned a lot from him.”

Although Tony doesn’t like to admit it, he also learned a lot about publicity from reading about James Dean. There was a slight similarity which his fans noticed, and Tony was not averse to emphasizing it. Like Jimmy, Tony is shy. Tony’s father died when he was five and Jimmy’s mother died when he was eight. Young people identify themselves with Tony as easily as they did with Jimmy, and all women want to mother him. Tony’s studio, Paramount, has great plans for his future as did Jimmy’s studio, Warners.

There are also important dissimilarities. Says D. A. Doran, the production head of Paramount, “Tony is not neurotic. Basically he isn’t one of the sod-kicking school, and generally avoids the studied slovenliness of Brando or Dean.”

There may be some difference of opinion on this point. However, the comparisons are inevitable, particularly when Tony frankly admits that he’s flattered to be compared with Jimmy. “I don’t like to be called the new James Dean,” he said, “but I don’t resent it too much because Jimmy was a good actor.”

Unlike Jimmy, who was always spending his money on whatever caught his fancy, Tony is very thrifty. He gives most of his money to his mother to invest, and admits he already has a sizable amount saved.

By Hollywood standards Tony is a loner. He has no close friends in the movie colony, and the only girls he dates are the ones he works with in pictures. During the filming of “The Lonely Man” he dated Elaine Aiken, also in the movie; now he goes out with Norma Moore, who plays his wife in “Fear Strikes Out.”

Still, Tony likes going it alone a good bit of the time. He prefers his own company to the theatre. ‘I’m always worried about the other person,” he says. “If he or she likes the play and I don’t, I worry. If he doesn’t like it and I do, I worry. It’s best to go alone.”

Tony was alone when he went to a sneak preview of “Friendly Persuasion.” He sat in the balcony eating popcorn. No one recognized him, and after the show he mingled with the audience to get reactions. What he heard, Tony shyly admitted, did not displease him.

Even when Tony goes to parties he frequently pays little attention to others. His first Hollywood party was one given by Paramount for Morey Bernstein, author of “The Search for Bridey Murphy.” Dressed far too casually, Tony arrived at the party late with Elaine Aiken. He nodded to some of the studio executives, pushed his way through to the bar, where he promptly downed two glasses of soda pop. With Elaine still on his arm, he attacked the anchovies and assorted hors d’oeuvres, and half an hour later they went home.

The story spread around town and created one impression which Tony wanted to give—that he was not a “dress-up guy.” Other impressions received may not have been intended.

Despite his seeming nonchalance Tony is very normal in many of his reactions. When he got an advance issue of a national magazine with his picture on the cover and a story inside, he ran around the Paramount lot with it, wanting to share his excitement.

The people he chose to share his thrill with tell a good deal about Tony. First he found Elaine Aiken and then Norma Moore. Next he brought the magazine up to show to D. A. Doran. He also showed it to Lindsay Durand, the publicist at Paramount assigned to national magazines.

Later that afternoon at Lucey’s I saw Tony, and he had the magazine with him. I asked if he had called his mother. Tony said she knew about the story and there was no point calling her; it would be out within two days. After telling me this he went to the phone and placed the call.

I was struck by the marked change in Tony since my first interview with him just six months earlier.

I had met him, coincidentally, at Lucey’s, with Mark Richman and Phyllis Love, his fellow players in “Friendly Persuasion.” He was just one of three new young actors then, but there was something different about him.

For one thing, he was dressed almost too casually. He wore blue jeans, a sport shirt and sneakers, and he seemed so unimpressed that I thought at first he was bored. I learned later that he was nervous but used the nonchalance as a cover-up.

At the time Tony said he had wanted to do “Friendly Persuasion” because he thought it would really be a good picture. If it were, it would increase his value in TV.

Tony knew that his part was great, a sure-fire winner for a newcomer. He also knew that it was far better than Mark Richman’s role, but he didn’t boast about it.

Instead he told funny stories about himself, how he was keeping a list of the turndowns he had gotten from various producers who said he was either too tall or too short or too fat or too thin. He suggested that I write a story about the various ways of turning down an actor without hurting his feelings.

Gradually I found myself paying less attention to the other two actors and more to Tony. It was an unconscious move on my part, largely because Tony not only was interesting but gave the impression of being “somebody.”

Six months later, again with Tony at Lucey’s, the impression of being somebody had been strengthened. He appeared relaxed because he was. He sprawled across the bench in the booth and answered questions directly and without embellishment. He seemed to be the very essence of cooperation, and if he said something he didn’t want quoted, he had no hesitation about saying, “Please don’t use this.” In just a few months Tony had become a professional.

When the bill for dinner came I agreed to pay, and suggested that he leave the tip. Unabashedly Tony said he couldn’t because he had no money in his pockets. He had forgotten to take any with him in the morning.

Before we said goodbye Tony said that he had almost decided against the interview. I had written a harsh paragraph about him a few weeks before, and Tony’s acquaintances were amazed that he would talk with me again.

“You know, those stories you printed were all wrong,” he said. “They just didn’t happen the way you heard them.”

I told Tony that the stories came from a good source, and that the day after my column appeared in print, I had heard that there was a marked change in him.

He laughed and admitted that the stories hurt him, but he insisted that they were not true. They were just an elaboration of small, unimportant incidents. Yet it seems to me that they bear repeating because so many people have substantiated them.

During the filming of “The Lonely Man” with Jack Palance, Tony was reported to be having dinner with Elaine Aiken and one or two other actors, when the auditor for Paramount came to the table. He asked if he could join them.

Tony said that the table was only for actors. The auditor stomped away, but not before telling Tony that he was never to come to his office except on business.

On another occasion Tony refused to let an electrician ride with him in the studio limousine, claiming that the car was for stars only. Word got around that Tony was feeling his oats, and on the last day of the film one of the drivers decided to teach him a lesson. He loaded his car with bit players and crew people before picking up Tony—last. Tony fumed all the way on the ride to town.

One of the other stars on the film told me that he had never seen such an ill-mannered boy as Tony, who was surly and completely without feeling for anyone but himself.

Stories of Tony’s behavior were no secret on the set, and Elaine had many quiet talks with him, as did makeup man Wally Westmore. I was told that the one thing which straightened out Tony’s attitude—and quickly too—was the fear that news of it would get into print and hurt him with his fans.

This is important to Tony. A publicist on the picture said that he had never before seen an actor who took his fans so seriously. “You tell him fans won’t like something and he won’t do it. This boy thinks the world of his fans, and he won’t take any chances on alienating them.”

Whereas most actors will complain about candid photos, Tony prefers that all pictures taken of him be candid. He doesn’t refuse to go into the still gallery for a sitting, but he feels that fans want to see him as he is, and that they aren’t interested in “pretty boy” pictures of him.

This attitude makes Tony a photographer’s delight. He puts no restrictions on the cameraman, and will pose for pictures anywhere. He even has no objection to a photographer breaking in on a meal.

If the Schwab set is any criterion of success, Tony is a sure bet. Everyone wants to be seen with him. The actor everyone wants to be seen with at Schwab’s is the actor to keep an eye on. There are other indications of Tony’s approaching stardom. He has been assigned the dressing room next to William Holden’s at Paramount, and is permitted in the commissary—even welcomed—in his faded blue jeans and old sweater.

Tony has had to order the switchboard operators at his hotel and the studio to carefully screen all calls for him because he is continually besieged by female fans.

It’s not that he is shy of girls. Far from it. He has been engaged three times, twice to the same girl, and not long ago to a millionaire’s daughter.

It may be that he is shy of marriage. The romance with the heiress was going along fine, Tony recalled, until the day he went to the airport to see her off on a trip. They were standing on the edge of the airstrip when Tony asked the girl what time her plane was leaving.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said. “We have time.”

Just then a DC-7 taxied alongside. The steps were dropped down, and Tony’s girl—the only passenger—went aboard her private plane.

That was the end of the romance for Tony. “I just couldn’t compete with that kind of wealth,” he said.

The girl he was engaged to twice went to California to try to get into movies; Tony didn’t want to get married. She has since returned to New York, and Tony says he hasn’t seen her.

“I’m a dedicated actor,” he told me, his face serious. “I shouldn’t really have a wife at this point. I would never see her. It’s better to wait until I’ve arrived career-wise.”

When he’s in New York, Tony spends most of his free evenings at the theatre or movies. He’s an avid movie fan and sees as many as three pictures a week.

His life in New York, like his life in Hollywood, is distinguished only by its lack of excitement. He has a five-room apartment in Manhattan’s West Fifties. It is furnished meagerly with do-it-yourself tables and chairs and a few of Tony’s paintings on the wall. For the most part the paintings are of rooms, doors or windows with people in the background.

In Hollywood, Tony lives in one room at the Chateau Marmont. The principal piece of furniture is a portable radio, which is tuned to popular music all day.

The only pictures in the room are of his dog and cat. The dog is named Punkie, after the cat in “The Actress.” The cat is a Siamese which Tony calls Mr. Banjo, after the song of the same name.

The only valuables Tony takes with him from place to place are his guitar and a gold pocket watch which he got as a high-school graduation present. He has had the guitar five years and considers himself quite good at it.

The closets of his room are noticeably empty. Tony doesn’t like to wear good clothes. He travels with one suit, one pair of shoes, four shirts and three pairs of blue jeans.

His days follow an orderly pattern— bed at ten and up at six-thirty. “I wake up every morning feeling like the prisoner of Zenda,” Tony says. “I can’t move.” Finally he forces himself awake and gets started.

Generally speaking, Tony is easygoing and good-natured, but withdrawn. A friend of his said, “He’s so withdrawn you almost expect to see him come out on the other side of himself.”

He also has a problem in accepting the fact that an ordinary guy with an ordinary—even good—background can be a success in a business where it’s romantic to come up the hard way.

After several films in Hollywood, Tony is becoming wiser. He’s learning that being a good actor is enough reason to have stories written about one. It is not necessary also to be a character.

My hunch is that soon the barefoot boy with cheek will turn the other cheek, and we’ll see and read about Tony as he is—an ordinary, nice guy who is a wonderful actor as well.

THE END

YOU’LL SEE: Tony Perkins in Paramount’s “Fear Strikes Out” and “The Lonely Man.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK