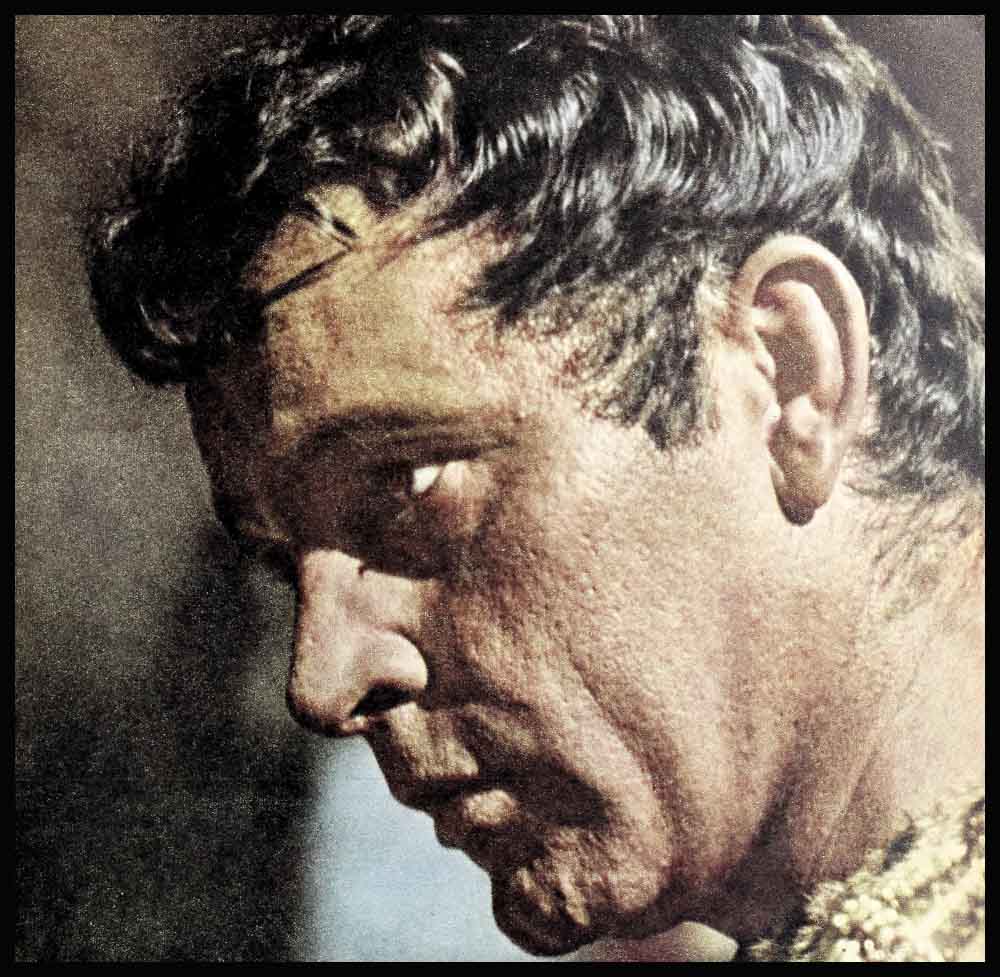

Richard Burton How He Got That Way?

PART I

Richard Burton—he was Richie Jenkins then—was a devil back in the late 1920s and early 1930s in the Taibach section of the town of Port Talbot, in Wales, where he grew up. And yet am angel he was, too, with a heart so good and rare as were tied to his insides with fine-spun gold. And it is strange (or is it really?) how all through the years that have followed it has bet the same with him—part devil, part angel. This little history his life —gathered from relatives and friends and enemies of a sorts, in Wales and in New York and in the town of Hollywood—shows it. Richard’s life began, in truth, one night when he was eighteen months old. The place was a tiny mining village called Pontrhydyfen in South Wales. The tiny house, made of pa gray stones gathered from the nearby quarries, was in the center of the village, not far from the black entrance to the coal mines that employed almost every man, woman and child around. I the parlor that night sat Old Dick Jenkins, the master of the house, a sawyer at the mines. A short, stocky man, part Jewish it was said, part Gypsy, but mostly passionate Welsh: a man who loved his drink and his fun and his family. The head of his family, too.

Around Old Dick that night sat his children, the multitude of them. There was Tom, the oldest, nineteen back then. Then Cecelia, or Sis, next in line and just turned seventeen. And—down the line—Ivor and David, Hilda, Catherine, Edie and William and Verdun. And finally, Richard, the youngest, who sat on Sis’ lap now and next to Sis’ husband, Elfed James, a miner, whom Sis had married five months ago.

AUDIO BOOK

They were a fun-loving family, usually, the Jenkinses were. They were a singing family, most times. It’s been said of them that even in a land of song, their voices stood out exceptional; a true cut above the average; that every tooth in their mouths had a bell, for song.

But this night they were quiet, solemn quiet, as they sat in that tiny living room of that tiny house waiting for the doctor, upstairs, to come down and give them the news they knew already would be bad.

For Mum Jenkins—wife of old Old Dick, mother of the brood—had been in childbearing labor, hard and painful, for more than six hours now. It was not easy for a woman of forty-five to be giving birth to her thirteenth babe (two of whom had died in infancy). This all of them in the room old enough to know about such things knew. And there was something in the air that night—Mum’s moaning, her crying, her heavy breathing, heard all the way from upstairs—that caused them to realize she was near her end.

It seemed hopeful there that moment, for one good moment, near midnight, when they heard the newborn cry. The babe, at least, had been born safe—thanks to Godalmighty. Tom Jenkins’ young wife, in fact, smiled a broad smile that moment and jumped up from her chair and rushed upstairs to see what was happening. The others remained seated—hoping but uncertain.

And sure enough, after a little while, the doctor appeared at the head of the stairs and he said, shaking his head, “It is sorry I am, but though the child is living, the mother is dead.”

For a while after that, they all remained in the living room downstairs, too stunned, too sad to move. But then, one by one, they climbed the stairs and went to the little bedroom to say the first of their goodbyes.

Sis was the last to enter the room—Sis and young Richard that is, whom she held in her arms.

“Richie,” she whispered, looking away from the lad and down at Mum, “take a long good glance at this good woman. And try to remember her. For your mother she was. A very beautiful woman she was. Remember that. There was no woman on earth that could cook like her. And miraculously clean she was. And good. The most wonderful woman on this earth. And if you do grow up to be like her, in the heart, with just a bit of her goodness—God will smile indeed.”

Sis looked away from the bed then, to the boy.

He was fast asleep by now. She smiled at him a bit. And then she looked over at her brother Tom’s wife.

“Dear,” she said, “you will take the newborn, yes? And Elfed and I will take Richard with us. And we’ll raise them as our own, yes?”

Tom’s wife nodded.

“Come,” Sis said then to her husband, “my little brother is our son now. Let’s us get home with him now and get him to bed. He’s so tired, he is. He has no idea of what is going on this terrible night.”

Again she looked at the sleeping boy in her arms.

The house’ on Inkerman Lane in Taibach, where Richard grew up, was no larger than the house over the hills and eight miles away, in Pontrhydyfen, where he’d been born and where he’d lived those first eighteen months of his life. It stood at the top of a hill named Constant. It contained four rooms—two upstairs, two down. In the back of the house there was, of course, a garden with a patch for flowers and a tree and a shed for bathing in the summer (bathing in the winter took place in the kitchen, for those who dared). And from the front windows, since the house was situated high, one could see—straight below—the entire town and the Margam Steel Works with its heavy cluster of high chimneys and the choppy waters of the Bristol Channel. And, to the right, a few miles away, the town of Swansea—or rather, as the local joke went, and goes: “When you can see Swansea, it’s a sign of rain. When you can’t, it’s pouring down!”

The house in Taibach was a happy place.

And though Sis now lives in a sweller place, down on posh Baglan Road, with ten large rooms—“my lovely present from Richard”-—she remembers the little house on Inkerman as being a heaven of sorts because her little brother was there with her and Elfed, and there was such an angel he was, that boy.

She remembers, for instance, that Richard was wonderful funny:

“He was just a chubby little thing,” she’ll tell you. “And he’d sit by the wireless. And there wasn’t a voice came over—from Cardiff, or London, or anywhere— that he wouldn’t imitate it to perfection. Neighbors would come over to hear him. Just imitating away. And laugh and laugh they would.”

She remembers that he was wonderful strong:

“His idol was Tommy Farr, the boxer. And, of course, all the rugby football players. Time was when we were sure that’s what Rich would certainly become—a professional football player. But the war changed that. And other things. But to keep up with his idols as a child, to get muscles like them, he would eat and eat. He’d love ham and grilled cheese. And eggs, of course. And most important—bacon and lava bread. What’s lava bread? Oh, it’s a most unsightly thing to look at. Ali black, with oatmeal. But Rich would always walk into the house and ask, first thing: ‘Any lava bread, Sis?’ And then he’d begin to eat it, and he’d say, ‘If there is better food in heaven, I am in a hurry to be there.’ ”

She remembers that he was wonderful friendly:

“He had more good friends than you could count on the fingers of both hands. People just liked to be with him. The boys —they adored him. And oh yes, he had plenty of girl friends, too. That is, the girls liked Rich. But until he was fourteen or fifteen he didn’t have much use for them. There were one or two—sweet-looking girls, nice as you can imagine—who’d actually come up to the house and sit around with me, just chatting and asking if they could help and generally wasting time, just waiting for Rich to come in with the hope that he might notice them. And when he would come in, he’d just look at them with this funny askance look and say ‘Hi’ for hello and ‘Ta’ for goodbye. And those sweet-looking girls, they would just be so sad.”

She remembers that he was wonderful religious:

“As a small boy he would love to attend chapel with us. Sometimes he’d even get up into the pulpit and give a little sermon of his own after the main service was over. Or else he’d go to the back of the chapel and sit playing the organ. He’d learned to play by himself, mind you. And he’d sit there and play all the hymns. I can still hear him, now, playing and singing his favorite—‘O Iesu Mawr Rhodt Anial Bur.’ So lovely he sang. So lovely.”

She remembers that he was wonderful close to the family:

“He just idolized his dad and all his brothers and sisters. Every week came and like clockwork I’d have to bring him back to Pontrhydyfen to visit them all and to see his little baby brother, Graham, now living with Tom and his wife. And if I were busy of a weekend and said that I didn’t think we could make it this time—well, Rich just made such a fuss that I had to take him. That’s how much he loved them all.”

And she remembers, most of all, that he was wonderful kind and considerate:

“Things were bad here in Wales when Rich was a boy. There was the depression. And the miners were out striking a lot of the time. There was always enough for food, we always had a nice table, and clean—but sometimes, you must admit, it was hard going, rough going. And one day, just a little chubby thing he was, I called Richard into the kitchen to give him his Saturday penny.

“And he said to me, ‘Do you know what, Sis?’

“And I said, ‘What, Rich?’

“And he said to me, ‘You wait. But someday I’ll be man. And I’ll be working. And I’ll be earning ten pounds a week. And then, you wait—but then I’ll help you and Elfed the way you’ve both helped me.

Yes, he was an angel young Richard was.

Just as others, close to Richard in his childhood days, remember the other side of him—the proper little devil that he obviously was, too.

Like Dillwyn Dummer—a jolly and lusty young man. Who, it happens, is second cousin to Richard. And who was his very best friend for many years. First, because they were the same age. Second, because they lived next door to one another—Richard at No. 3 Inkerman, Dillwyn at No. 2 (where he still lives). And third, because, says Dillwyn, “We were both rascals, and just tended together. Oh we were bad.”

Dillwyn remembers, for instance, that time with the pipes:

“My grandfather had this rack of pipes, you see? And one day—I guess we were both about six and not a minute older—Rich and I decided what fun it would be to sneak out the pipes and have our- selves a few good puffs. We went to the backyard. We lit a pipe apiece and we smoked away. We didn’t feel very well after that. An uncle of mine—Ivor—who sat watching us from an upstairs window swears we were the same color of the grass by the time we were finished. Uncle Ivor laughed all through it. But when my grandfather found out what we had done, he didn’t laugh a bit. In fact, a regular hiding Rich and I got from him.”

Dillwyn remembers, too, about Rich and his organ playing:

“He did learn to play by himself, that’s true. Next door to my grandmother’s on the great big old organ she had bought as a bride. He would sit there and practice, and play away, ali those hymns. And Rich’s sister would be so proud. And my grandmother would be so pleased. She would say, ‘How lovely—what lovely stuff he plays. Oh, I can’t wait to hear him in chapel come Sunday.’ Only what she didn’t know—what practically no one else knew—was that Rich was less interested in playing in chapel on Sunday than he was in running down on Monday night to our local pub—The Somerset Arms, that’s its proper name, though we used to call it The Scare—and sit himself at the organ they had there and play for all the half- tanked blokes who were just itching for anyone to come along and accompany them in their half-tanked singsongs.”

Dillwyn remembers the games he and Richard used to play together:

“Good jokes they were really. We’d clown around so much my mother used to be afraid to have Rich knock on the door for fear of what we’d get up to. Like we’d run out of the house and go over hedges and through gates, climbing rock outcrop, brushing our way through the bramble and the gorse—just for the silly fun of running. Or we’d go to someone’s garden and pinch carrots. And we used to play rat-tat—that’s knocking on somebody’s door and then running away, fast. Or we’d put a cord on a tin can and put it through the knocker of a door, stand way back and pull it. And run again. Run like hell.”

He remembers their Saturday afternoons at the movies:

“Regular weekly clients we were over at the Taibach Picture Dome. And the more noise and racket we made, the happier we were. Especially if it was one of those love pictures. These especially used to bore Richard to tears. He’d sit there making the biggest kind of racket—‘All this kissing and smooching,’ he’d say, ‘ha ha ha ha ha!’—until the people around us used to call out to hisht and for shame.”

Dillwyn remembers, very well, what happened to them both one Saturday night right after the movies:

“Part of the pleasure of our going to the cinema was to smoke. And many an empty packet of fags we chucked over , the bridge and into the railway yard on our way home. And this one night—it was right at the beginning of the war, blackout time, pitch dark; we must have been all of twelve or thirteen by now—we were Crossing the bridge and were down to our last two cigarettes, which we somehow hadn’t managed to smoke yet.

“‘Got a match?’ Rich asked me.

“ ‘No,’ I said, ‘I’m all out.’

“ ‘Got two fags left,’ Rich said.

“ ‘Guess we’ll just have to get rid of them,’ I said. ‘You know what will happen if someone finds them in our pockets.’

“ ‘Nonsense,’ Rich said. ‘We’ll grab a light from someone. Ah here—’ he said, ‘here comes some fellow.’

“I looked to where Rich was pointing and yes, I could see him, in the darkness, this fellow coming.

“ ‘Can I have a light. please?’ I heard Rich ask then.

“ ‘Hullo? What’s that?’ this fellow said, in a voice proper angry.

“This fellow, it turned out, was my father. And we got a light all right. Smack on the seat of our pants.

Not far from the railway bridge where the cigarette incident took place, and at the foot of Constant Hill, sits the small schoolhouse Richard attended as a boy—Dyffryn Grammar, it is called.

While many of the men who taught there in the early ’40s are gone—either dead or retired or moved into other towns, other schools—a few remain who remember Richard.

One of these, who prefers to be nameless, remembers him perhaps better than anyone else:

“He was a bright boy—not that there weren’t brighter. For a while I thought of him as one of those many children from I poor circumstances who would just be weighed down by the poverty and go on to lead an ordinary hum-drum life, the brightness going for nought. But I believe that in Richard’s case there were factors—despite himself—that tended to lift him from such a fate.

“One was his intense devotion to his I sister, that fine and lovely woman Cecelia—a desire to pay her back somehow for everything she had done for him. Yes, the devotion between these two was intense, intense.

“Another factor was an innate desire in the lad to possess material things for himself. I remember that he was always very interested in automobiles. Once during class I noticed that he was paying absolutely no attention to what I was lecturing on. I walked—I should say, I tiptoed—over to his desk to see what he was reading while I was talking. It was one of those magazines about cars. He was turned to a page describing a Rolls-Royce. I said to him, ‘Rich—do you intent buying one of those someday?’

“And he looked up at me without a blink and he said: ‘Why yes, Sir—I do.’

“A third factor was his vitality—a very vital young character young Richard was, ardent in everything he applied himself to. It became more and more apparent that in the end this application would be involved with something larger than ordinary life, so to speak.

“And a final factor was his personality—a strangely loveable personality—which made him much loved by two magnificent men who were to take a vast interest in him in his early teen years and who were to be vastly instrumental in the shaping of his life, and his subsequent career.

“Both were teachers here at Dyffryn. One was the late Meredith Jones. The other—P.H. Burton . . . the great P.H. Burton. . . .”

“Meredith Jones,” Richard Burton wrote to some friends in Wales recently, reminiscing about the old days, “was shortish and tended to obesity. Quick-thinking and quick-talking to the point of brilliance, he was a great teacher and master of many arguments. He was all electricity, sparkling and flashing; his pyrotechnical arguments would occasionally short-circuit but they were never out of power. Putting his rare personality down on paper, as Lloyd George once said of someone (or vice-versa), is like trying to pick up quicksilver with a fork.

“Dear Meredith Jones—dead now for some years, I lament him still—with his breath-taking effrontery and his eloquent and dazzling generalizations, hurled and swept me into the ambition to be something other than a thirty-bob-a-week out-fitter’s apprentice.”

What had happened years earlier between Meredith Jones and Richard Jenkins was this: Richard. at fifteen, decided one day to quit school. When his sister asked why, he said simply, lying, “Because it is bored with it I am.” And so he quit. And so he took a job as clerk in the men’s clothing department of the National Cooperative Stores, a large British chain.

And it happened one day that a former teacher of Richard’s—Meredith Jones—dropped by Sis James’ house for a cup of tea and a chat.

“Don’t you consider this shocking, Mrs. James,” asked Jones, immediately and to the point, “that a boy with Richard’s promise has left school?”

“I do,” said Sis. “It does seem shocking.”

“Do you know why he left?” asked Jones.

“Because he was tired with it.” said Sis. “At least, so Rich said he was.”

“Do you think this is true?” Jones asked.

Sis shook her head. “No,” she said.

“What do you think?” Jones asked.

Sis paused for a moment. Then she said, “That he pitied our circumstances in these troubled times and wants to help me and Elfed as much as he can. I didn’t realize this at first. But I see it on Fridays now, Rich’s pay day, when he comes home and gives me the money he’s earned. It is the only time I see Rich smile these days.”

“You think he’s unhappy, then?” Jones asked.

Sis nodded. “I think so,” she said.

“Do you think, Mrs. James, that you can talk him into giving up his job and returning to school?”

“But won’t that be impossible, Mr. Jones? / think it will be. Secretly I have already inquired about this, and I have been told that it will be impossible indeed.”

Meredith Jones smiled a little. “I am, in all modesty. a man of some importance in the school system, Mrs. James,” he said. “And I’ll tell you this. If you talk to Richard, and if he indicates that he is at all interested in returning. I shall try jolly well hard to get him back in. And I will. I swear with my blood that I will.”

That night, Sis had a talk with Richard. Yes, the boy admitted, after a long hard pull: he had taken the job only to help out; he was unhappy; he did want to go back to school.

The next morning. Sis James went for a chat with Meredith Jones. For the next three long weeks, Jones pulled every string he could with the rather severe Glamorgan District Educational Committee to have Richard Jenkins re-admitted to Dyffryn Grammar.

And then one afternoon. three weeks later, Richard walked into the little house on Constant Hill. Sis, upstairs cleaning at the time, could hear the downstairs door open and shut, then Richard shout up to her. “Sis—I have wonderful news.”

She took a deep breath. She walked to the top of the staircase.

“Going back to school, Rich?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said.

And they rushed towards one another —big sister and little brother. And they hugged. right there in the middle of that staircase. And. suddenly, they began to weep. But not with sorrow—with joy.

And so was Meredith Jones—“I lament him still”—important to young Richard’s life and the years ahead of him.

The other teacher, P.H. Burton, came into Richard’s life about a year later—-in 1942, in fact, when Richard was sixteen. To understand better the relationship between the two, it’s important to know a little bit about P.H. First.

Says one man in Port Talbot who knew him well, “P.H. Burton was one of the great teachers—pedantic, didactic, precise. He was always desperately keen on theater. In fact, his life’s ambition was to become an actor himself. But he had a failing. He was a big man, some six feet tall, weighed a good fifteen stones. But for all his bulk he had a sweet small voice, very much out of keeping with his frame. And so he became a developer of actors, rather than an actor himself . . . His first protege was Owen Jones. P.H. discovered him here, trained him here, gave him all the instruction he could. The time came when young Jones was on the threshold of stardom. But then the war came, too. And Jones became a flier. I believe it was. And he was killed in 1942 . . . That’s when P.H., as he sought another student. another star to replace Jones, cottoned onto Richard Jenkins. Rich was sixteen then. He’d returned to school after a short absence and was doing very well in his studies. I doubt that the idea of theater or theatricals had ever really entered his mind. But one day P.H. announced suddenly to one and all that he saw in young Rich the stuff of which great actors are made. And I don’t doubt that of one and all, the greatest surprise in this matter came to young Rich himself.”

P.H. began by giving Richard the leads in two Taibach Youth Centre productions —“The Playgoers” and “The Bishop’s Candlesticks.” (This was October, 1942).

Satisfied with the boy’s performances—though not overly—P.H. then began to concentrate on a program of refinement.

One afternoon after classes he had a talk with Richard.

“Would you like to become an actor— truly—some day?” he asked.

Richard shrugged. “I hear they make fine money. Why not?”

“The good ones,” said P.H.. “make the good money.”

“Then I shall be good.” said Richard.

“Fine,” P.H. said. “But the first thing we have to do is to get rid of all the Welsh in your talk. That won’t do at all, you know. You must learn to speak like an Englishman.”

“I’ll be damned if I’ll do that,” said Richard.

“I’ll be damned if you don’t,” said P.H. “What is it with you, young man? Do you want to play peasants for the rest of your life? Or do you want to play princes? And kings?” Without waiting for an answer, P.H. went on: “Next . . . we’ve got to get you to read better stuff than you’ve been reading. You have a basic intellectual capacity. But we’ve got to work on it. What’s that you’re carrying under your arm right now?”

“An American crime book. Very good.”

“Bah,” said P.H. “It is Shakespeare you’ve got to start reading now.”

“That bloke?” asked Richard, in doubt.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments