The Magic Of Dorothy McGuire

Sometimes a child is born touched with magic as priceless as that which fairy godmothers were wont to bestow in the old stories. It surrounds her like an aura and when she walks into dull, dark places, they seem to light up suddenly.

Dorothy McGuire must have it. That must have been why, when Violet Heming saw her, at the age of thirteen, playing the slavey in “A Kiss For Cinderella” at the Omaha Community Playhouse with Henry Fonda, she exclaimed, “The child has the spark . . . that thing, whatever it is, that means everything in the theater.” . . . And Violet Heming went back to Broadway to talk to veterans of the stage about the wonder child she had seen in the middle west.

That must have been why, when Dorothy walked into John Golden’s Office, tired and discouraged, her hair tousled, a smudge on her nose, Rose Franken recognized instantly that here was the heroine of her play, “Claudia.” It hadn’t been a nicg day for Miss Franken or Golden, either. They had been interviewing scores of possible Claudias without success and they were tired and hot. But there was that glow about Dorothy that decided the issue for them.

David Selznick recognized it later when he saw her in the play and, smart showman that he was, signed her to a long term contract.

Probably no actress since the very young Janet Gaynor has had that exact, strange quality—the power to be luminous in the dusk—and producers have made good use of it in the drab, yet strangely exciting roles they have given Dorothy in “A Tree Grows In Brooklyn” and “The Enchanted Cottage.”

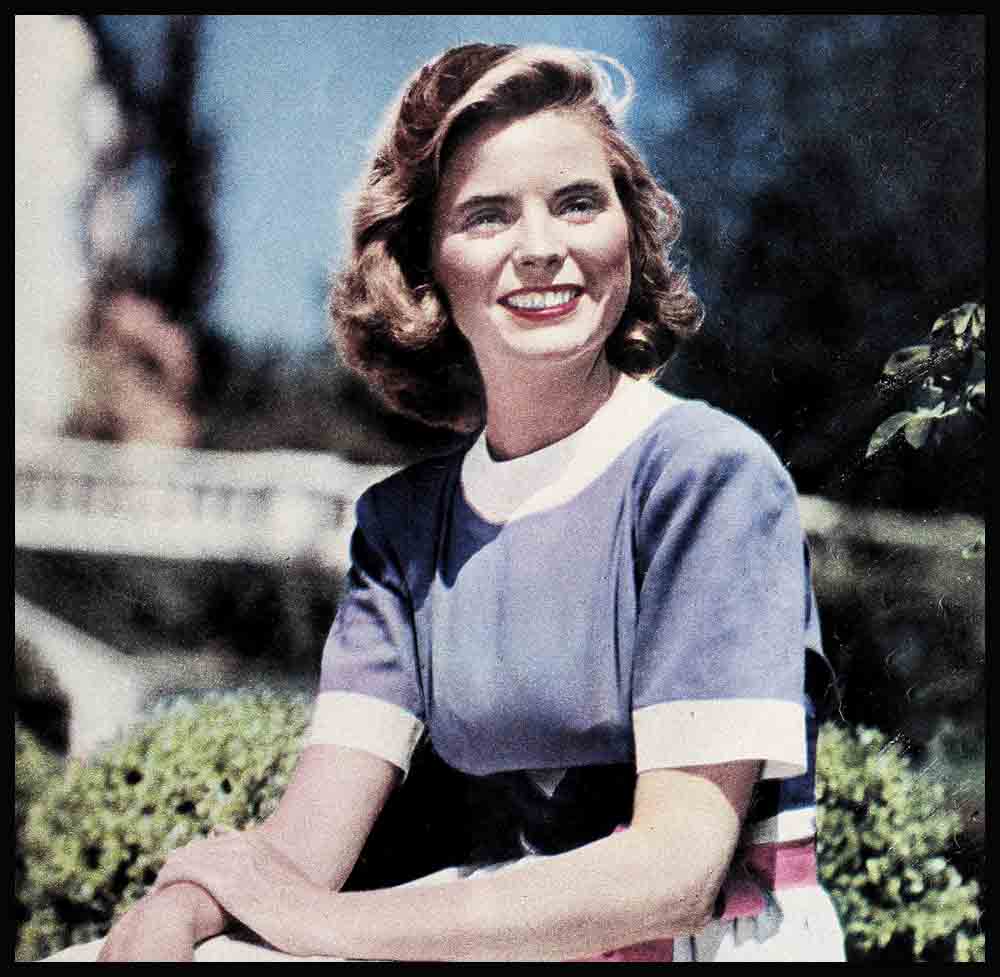

She doesn’t feel luminous . . . to herself! She doesn’t glow especially to a casual stranger, meeting her for the first time, either. She is a tali (five feet seven inches), modest, brown-and-blue person and on the set of “The Enchanted Cottage” everyone called her “Cupcake.” They couldn’t explain exactly why they called her that. There was just something wholesome and sweet and unpretentious about her which made the name seem to fit. Grips and a few others called her “Miss Cupcake.”

There doesn’t seem to be the slightest excuse for her special knack for playing drab roles, either. Daughter of a prosperous Omaha, Nebraska, attorney, Thomas McGuire, and his wife, Isabel, Dorothy led an almost pampered life when she was very young. A friend who knew her well in her little theater days says that she was gently reared, sheltered and always so exquisitely dressed as to be the envy of a good many other little girls. She attended the Ladywood School at Indianapolis and went on to Pine Manor at Wellesley, Massachusetts. And when she went to Ne w York to try her luck on the stage she was never in any danger of starving, never had to live in a garret for even a week.

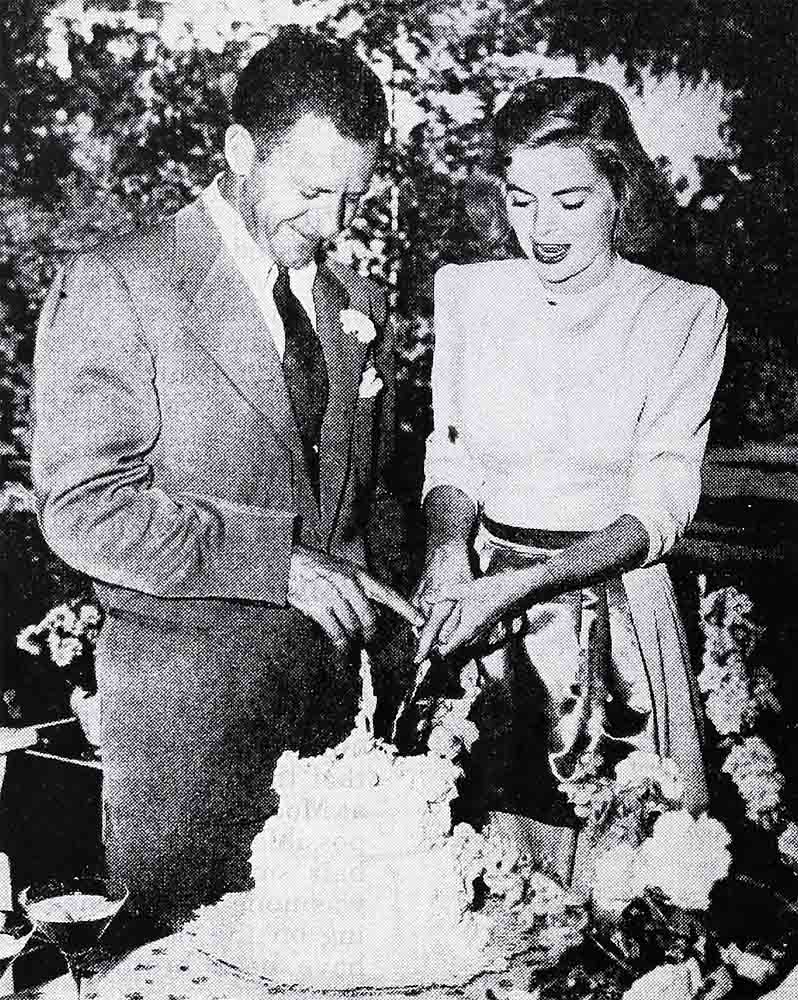

While she was playing in the hugely successful “Claudia” in New York, her friend, Helen Morgan Elliot of Life Magazine, brought two brothers backstage to meet her—Rob and John Swope. Later on, when she came to Hollywood to make the picture version of the play, John called her and invited her to dinner. By that time he had become a member of the lighthearted Jimmy Stewart-Burgess Meredith-Henry Fonda group which spasmodically inhabited a surprising “bachelors’ hail” on the outskirts of Culver City. A few months after Dorothy arrived in Hollywood and after one of the quietest courtships on record the pair were married in a simple garden ceremony at the home of the Leland Haywards.

John is an aviation enthusiast and an expert photographer. He published a pretty good book, called “Camera over Hollywood,” just before he went to take charge of Thunderbird Field near Phoenix, Arizona.

Just here this story begins to sound a little bit unreal. Here was Dorothy, who had signed a fabulous motion-picture contract and had been hailed by critics as one of the coming screen actresses. She was newly married to an interesting and certainly an ubiquitous young man. And where was she? She was in a funny little house, two miles outside Phoenix, doing most of her own housework, that’s where she was. Cleaning women were as scarce there as they are anywhere else and for the first time in her life, Dorothy found herself coping with dish mops, brooms and dusters. She was there for some months so she had time to learn a good deal.

When she came back to Hollywood to play in “A Tree,” she found that Elia Kazan, the director, believes that dialogue is more effective if the characters are engaged in natural activity while speaking . . . and the suitable activity for the characters in that picture was nearly all domestic routine. So, for the camera this time, Miss McGuire found herself once more dealing with dish mops, dusters, scrub brushes and washtubs and feeling pretty expert about it.

“Nobody ever told me an actress’s life would be anything like this!” she sighed, leaning on her broom. But something very like it happened to her again when she went into “The Enchanted Cottage.”

Actually, she thinks, she isn’t at all a domestic person. When she was living in New York she acquired a modest flat and furnished it with antiques which she picked up here and there in a distinctly haphazard fashion. The first thing she bought—before she even had any chairs—was an elderly melodian (for thirty-five dollars) and she went instantly to work, learning to play it. One by one she acquired a table, a settee and a few chairs but when she gave her first party most of her guests elected to sit on the floor “because everything looked so extremely fragile. . . .”

Despite her recently acquired domestic accomplishments, Dorothy’s consideration for the purely utilitarian in life is likely to remain elemental.

Her first home in Hollywood, however, was purely utilitarian . . . and that was all it was. The housing shortage being what it was, she snatched eagerly at the opportunity to rent a furnished apartment somewhere in the vicinity of her studio . . . and she rented it without ever seeing the inside of it, which was, one gathers, a touch depressing. But it was a roof. She says that was “heaven enough, just then.”

However, once installed in the stereotyped little home, with the maid, Bertha, who had been with her family for years, Dorothy set about earnestly and fearfully trying to he a motion-picture actress. Hollywood ballyhoo frightened her. The hazard of making the transition from stage to screen had seemed a big one to her, in the first place. “Then,” she says, “I was appalled to find that when one has come from the theater, she is supposed to know all about ‘acting.’ In the theater—actually—it is supposed to take you years and years to learn the rudiments. You don’t expect, in your most optimistic moments, to be recognized as a ‘star’ until you have served a long, gruelling, earnest apprenticeship. Here I found that you were a ‘star’ because someone said you were. . . . It was terrifying.”

Another thing that appalled her when she was first here was that she was always being compared to someone. When it became apparent that she was a direct person who said what she meant, with no frills on it, she was dubbed “another Hepburn.’’ When she was seen walking alone in the hills or on the beach it was, of course, “another Garbo.” Her first stills brought the tag, “another Gaynor.” She was indignant. “I can’t be ‘another’ everything,” she protested. “I feel like a mince pie . . . composed of goodness knows what!”

She has interesting theories about clothes—colors, fabrics, lines—and the moods they produce. She likes to talk about her theories but rarely troubles to practice them. Odd combinations of clothes captivate her—sweaters with evening skirts, halters with dinner trousers, novel combinations of colors and fabrics. But when novelties become fads, she loses interest in them. She enjoys lovely brocades, woolens, homespuns, delicate laces . . . but she enjoys them quite as much on someone else as she does on herself. Her personal taste, especially in daytime clothes, is casual—a suit with a spanking fresh blouse or a skirt with a bright sweater.

She admits that clothes affect her . . . thinks they affect any normal woman . . . and she found the drab costumes in “The Tree” and “The Cottage” a touch depressing after weeks and weeks and weeks. One of her most wistful desires just now is for a role in which she may wear pretty clothes “all the way through the picture!”

For she is really a gay creature. She says that what she loves most in the world is “comfort.” This seems to mean warmth and light, the company of the people of whom she is fond and the opportunity to discover new ones. It includes lots of outdoors—space and light and exercise—good conversation and good food, prepared by someone else, from ingredients of which she doesn’t even know the names.

Recently she was in New York with John. They were stopping at the Plaza and Dorothy was dreamy-voiced with pleasure over her vacation. They had spent some time in the country where she had met her husband’s family for the first time and they were going back for week ends.

“In the country,” she said, “we take long walks in the snow, skate on the lake, work in the dark room developing photographs, talk—and talk—read, listen to the radio, sit by log fires.”

New York was wonderful. The big city excites and stimulates her, and she says she feels “more alive there than anywhere else.” She and John saw a lot of plays, got very excited about “The Hasty Heart” and the musical ballet, “On The Town.” They browsed around the Battery, Chinatown, the Bowery, East Side, Times Square. They rode on buses and visited art galleries. She had bought a gray wool skirt. You gathered that, despite the fact that she had lived in New York for several years, it was an entirely new and fresh experience to be there with John. She might never have seen the place before and they might have been discovering everything together for the first time.

She has never been able to make herself like large parties. “That,” she observes, “is merely my ego. I’m not good at a large gathering. I like to ‘discover’ new people, I get mental stimulation from the impact of new personalities and minds. But you can’t do that in a crowd. Everything is too fleeting, moves too fast. I enjoy small groups of people who like to just sit down and talk. . . .”

Her hobbies, she says, are all expensive ones.

“We—John and I—are both interested in paintings and old silver and china. Just now we are in the ‘finding out’ stage. We’re trying to take an intelligent interest in the things that fascinate us, so that we’ll know what’s really good—and so that we shan’t make silly purchases. It takes quite a long time and quite a lot of study really to know.”

She is not good at figures and she is filled with worshipful admiration when John copes easily and accurately with something like a bank statement or an income tax blank. But she has what she calls a “horrendous memory” for what she, herself, has bought and what she has paid for it.

“Sometimes these details stay in my mind for years,” she muses. “Sometimes they haunt me and often they even make me slightly dyspeptic . . . but I always remember. . . .”

She likes hats but she rarely gets round to buying them, somehow.

She loves to drench herself in spring-flower-scented colognes—“the kind of scents that don’t smother me.”

She is sentimental about holidays—can’t imagine Christmas without a tree or Thanksgiving without a turkey—and she would be wistful, indeed, if she didn’t receive a red satin box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day.

Her plans for her immediate and more remote future are flexible and necessarily nebulous. As this is written, she is planning to go overseas in a USO Camp Shows unit of “Dear Ruth,” the Broadway hit play.

“It is a difficult time to make any plans at all,” she reflected, “let alone work out any sort of pattern of living. There are so many things we hope to do together— John and I. Some of them are too serious, too much loved, too close to our hearts to even talk about now.”

They like to travel and they hope someday to be able to do a great deal of it together.

“I like to go with John when he takes pictures. He has a quality which I can only describe as ‘comfortable’ which makes people like him and consent to co-operate with him almost at once. So—we should like very much to travel and make pictures.”

Despite the fact that she has sold one or two articles to national magazines, she says she has no burning desire to write. “I really haven’t,” she says, thoughtfully, “the equipment!”

They are both passionately addicted to flying. Dorothy has already had some experience at the controls of a plane and she is anxious to become at least a “dependable flyer” so that when they go places together in a plane she can relieve John at the controls. It is the most fascinating way to go places, see people, see the country—and these things are important.

“As for the actual handling of a plane, I can’t tell you how exciting it is!” she breathes.

“In the first place, you are aware that you are doing something which is an expression of our era, our generation. It’s—well—it’s something to be a part of the generation which has conquered the air! Then, when you are up there, you are released from everything mundane. You are captain of your soul, mistress of your destiny. The petty things all fall away and you see . . . clearly . . . ! For that moment you’ll be afraid of nothing.”

That is Dorothy. May she never singe her shining wings.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1945