Westward—Ha!

Seeing’s that you asked me,” said Shirley MacLaine, as she curled her feet: under her in the barrel chair and almost disappeared into her knees. “Yup. I like it here.” She flashed a lightning smile that lit up her face.

“Lots of people say that Hollywood is a good place to work, but no place to live. You know the idea—long on fame and fortune, but short on personal happiness. I don’t think so.” Shirley rolled her tongue around in a gesture that acknowledged thought and locked her arms around her knees. “I think happiness s highly personal and that you can be happy wherever you are, if you’ve a mind to. I’ve learned a lot about how to be happy from my husband Steve Parker—but you know who gave me a real philosophy? Stephanie!”

Stephanie, the first of three children the Parkers resolutely plan on having, was born last October and very shortly after that, life unfolded for Shirley MacLaine depths and nuances she hadn’t suspected it possessed. Suddenly there were no more trials or annoyances or inconveniences.

“It was the most remarkable discovery,” she said not long ago. “For me anyway. Maybe everybody else already’s found it out. But it was just this: You can have just as much fun enjoying a job as you can not enjoying it. Well more, naturally. But do you think I’d figured that out until this one came? Not for a minute. It all goes back to Steve.” She calls Stephanie Steve. Sometimes Stevie.

“Thing I’ve found out,” Shirley MacLaine said, “is—oh, I suppose child’s play to anyone else. But I had to discover it the hard way. At least, that makes it mine.”

Interviewing Shirley is like being on a roller-coaster ride—it’s exhilarating, surprising and covers a lot of distance. Our conversation took us through the house, out the exit, onto the back porch. Shirley stood up on a railing, leaned against the wall of the house and placed her hands on her knees.

“Take pictures. When I came out here, I thought the part before the camera was everything, the actual moments of the take, and now of course I know it’s nothing but the very end product and all this enormous work builds to it. But I didn’t know that. And the preliminaries, they were just something, far as I was concerned, to be got through. To hold still for. Make-up. Stills. Rehearsal. Study. Interviews. Even driving to and from work. I made them ordeals in my mind. Not bad ordeals, heaven knows, but something to survive, not look forward to. Then Steve was born, and my whole life changed and it was a whole new way of being—I didn’t know it but I hadn’t even lived before—and all of a sudden, it was so simple, the idea came to me, ‘If you’ve got to do it, why not enjoy it? Whatever it is? What have you got to lose?’ And I did try to do that, and darned if I couldn’t, and it changed things.

“I’m not going to be twenty-three till April and I’m certainly not setting myself up as a poor girl’s Norman Vincent Peale, but I did find this out for myself and anybody else who wants it can have it. Steve—this Steve here—gave it to me, so why shouldn’t I pass it on? You see, when you’re as happy as I was with Steve, and of course, her father, too, then you’ve got to enjoy everything. You can’t help it. And once you’re in the habit, you don’t stop. Hairdriers, mountain roads, critics, make-up, just waiting, I don’t care what it is—name it, and I’ve learned to find out what’s best in it and to lean on that. It’s my discovery for this year, and it goes right back to Stevie.

“End of philosophy!” she laughed, and we went back into the house. “Sure I like Hollywood,” she said as she turned to me, “but happiness isn’t something that has a time and place. It’s the people you’re with, and the things you’re sharing. Isn’t this nice?” She pointed toward the view of the ocean, and the churning of the waves. “I call that the Parker House roll.” We both laughed. We were in the rear of the house, in a room with picture windows facing the ocean and a little stretch of beach the Parkers may call theirs so long as they pay the rent. They rent the home on a year- round basis (rent one of these jobs for the summer season only and they bump you $1,000 a month) and hope to buy it when the rental period expires. It is an attached house, one of a number at the north end of the colony, and contains a housekeeper, a young boxer dog with a superficial resemblance to Herbert Hoover, Stephanie, and a good deal of sand. The sand does not ruffle the Parker family. “We chose to live on the beach,” Shirley has said with something like bristling vigor, “so we expect sand on the floor. People who don’t want sand on the floor shouldn’t live at the beach. You can’t have it both ways.” Stephanie, in the next room, clung to the edge of her play-pen. Shirley MacLaine is absolutely right: Stephanie is inspirational. Husky, too. Pretty soon Shirley couldn’t stand it any longer and went over to the play-pen and lugged Stephanie into the conversation. “We’re going to take her to the doctor,” she said to Stephanie. “Yes, we are. We’re going to take her to the doctor and she’s going to break the scales.”

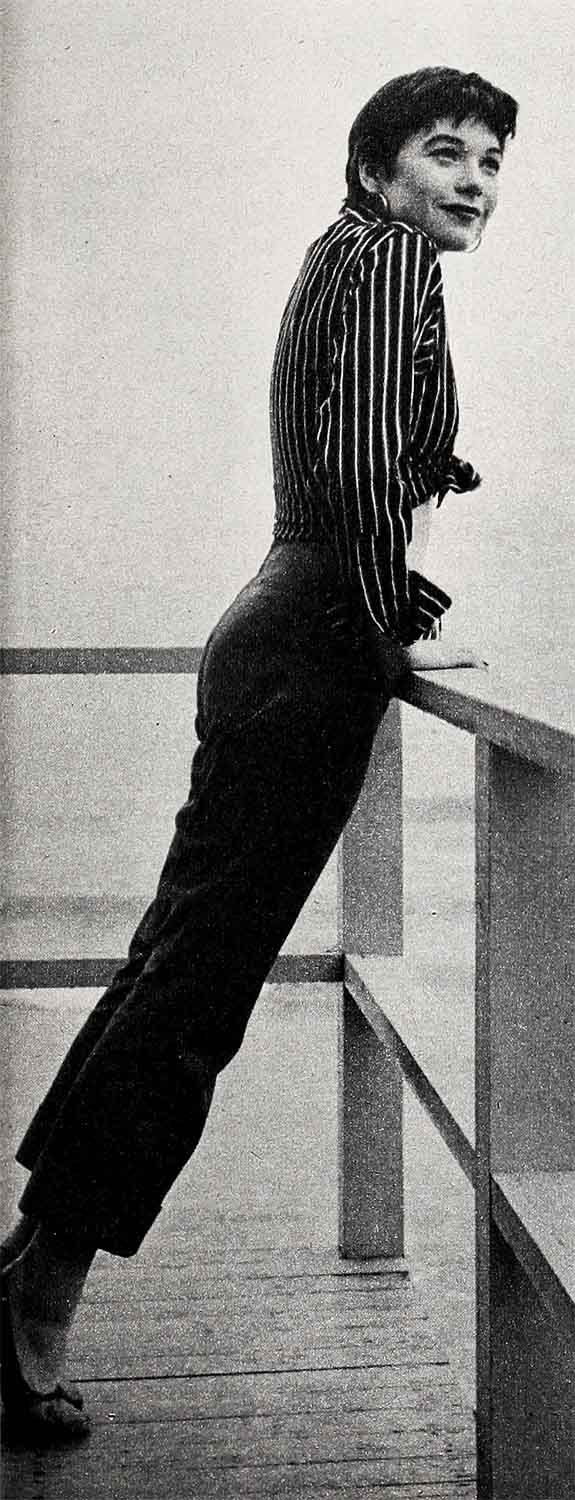

Stephanie’s gamin-faced mother wore a striped shirt and pedal-pushers. Loafers. This was a day off but she’d gotten up pretty early anyway, eight o’clock or so and walked a mile and a half down the beach to what is called Malibu Pier, and then back again, happy in the feel of the sand, and then a very big breakfast. It was animal spirits, real joy. She loves the beach and would not live elsewhere in Southern California, although dream’s end for the Steve Parkers is a farm in Vermont: “We’ll work it and smell it and live with the seasons.” They all but know what farm and where in Vermont. And one of these years, Shirley MacLaine and her gifted husband will turn their backs on Hollywood for the state they love the best, where even the summer nights get cold and the winters are virtually polar. And there, she says, they will farm.

“Without a single regret?” The projected transference seemed implausibly drastic.

“Without a single regret,” she said. “You’re talking about career and climate and things like that, I mean? No, because then this phase of our lives will be over, and I wouldn’t look back on it if I could. Now it’s here and we’re here, except Steve’s in Japan, and it’s fine. That’s what I’ve been talking about, loving things in and for the present. But next year or in five years or however many it is—and I don’t really know—we close it out. And it’ll be Vermont, and you know, there summer is summer and winter’s winter and the hills blaze up in fall, and in the spring—Well, it’s not Hollywood, if you follow me. Then I won’t care if I never see another glossy restaurant or an auto- graph album or a sound stage, and I’ll just be Shirley Parker, but truly.

“It’ll have to be that way. I know I’m young, and I don’t want to talk out of turn, but I feel sad sometimes for some of the great stars out here who can’t seem to let go of what they’ve achieved. It’s almost as if they’re hopelessly stuck with it. Ambition’s great—I have a good stack of it myself—but if I thought it were getting to be more than I could handle, I’d skedaddle for Vermont tomorrow. This so-called fame seems to make it so easy to lose perspective. Ambition’s a necessary weapon, I’m pretty sure, but if it gets to be your master, you’re in trouble. Dr. Frankenstein bit off more than he’d intended to, didn’t he? No, sooner or later itll be Vermont and goodbye, Sunset Boulevard. Not au revoir—goodbye. But today it is Hollywood, and I’m having a ball. I’d be an ingrate and something of a liar, too, if I said anything else. It’s wonderful.”

Stephanie squirmed on Shirley’s lap and was regretfully put in the play-pen. Her young mother executed a small, restless entrechat, the ballet maneuver in which the dancer leaps into the air and gets very busy with the ankles, and sat down again, her back to the window. Behind her, the combers rolled up the steep little beach; it was something like a postcard. The Chamber of Commerce had dreamed it up.

“I credit whatever success I have,” Shirley continued, walking over to pat the dog, then Stephanie, “to hard work, ambition, good teachers, coincidence, my husband’s help and devotion and Carol Haney’s weak ankles. Especially the ankles.”

Shirley MacLean Beaty Parker was born in Richmond, Va., on April 24, 1934, the daughter and elder child of Ira O. Beaty, one-time musician and bandleader who today sells real estate, and the former Kathlyn MacLean, dilettante actress and for a while a dramatics teacher at Maryland College.

At 16, Shirley danced her way into the chorus of a revival of “Oklahoma!” and then “Kiss Me Kate” before she returned to Washington and Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia “to finish.” After graduation, she did TV commercials and guest shots, modeled for stores and photographers, spent summers dancing with Washington’s National Symphony Orchestra and one fine day turned up in the chorus of “Me and Juliet” back in New York. That wasn’t significant in and of itself, but it gave her the fundamentals to try for a specialty spot in Fred Brisson’s “Pajama Game.” Shirley not only did specialty dance work in that, she also understudied star Carol Haney—who promptly (it was the third night of the run) broke her ankle. Just like in the movies.

In the audience the very night that Shirley went on for Carol was filmster Hal Wallis, who’d come to see Miss Haney, and was pretty much overwhelmed by what was served up instead. Did he say, “Sign that girl!”?

Not quite. What really did happen was that Wallis did go backstage and was spotted by Miss MacLaine before he saw her. “Are you,” she asked, moved either by premonition or a feeling of having seen this plot before, “looking for me?” And he was, and she has lived happily ever after. Wallis signed her to a contract virtually there and then, and not long afterward she made a memorable test, directed by the same Daniel Mann who turned out for Wallis “Come Back, Little Sheba” and “The Rose Tattoo.”

The test is notable for the fact that it contained no preconceived material. Miss MacLaine just did a little dance step without any music, then talked about herself. The whole business is today a cherished film in Paramount archives and still viewed by charmed Hollywood onlookers. These credit Shirley with the entire triumph. She credits Mann.

“It’s the way we react to each other,” she says now. “It’s total professional accord. We don’t always see eye to eye, but I believe in him implicitly and I relax with him. Wait for ‘Hot Spell,’ please. I honestly think you’re going to like it. It’ll be another one for Danny.” Or for Shirley Booth. Or quite possible for Shirley MacLaine, who is happy over what she has to do.

“I really just had to walk through ‘Eighty Days,’ ” she has said. “Cantinflas had the best part. But this is different.”

Back in New York after Wallis’ departure, Carol Haney got well pretty soon—well, it was a month—and Shirley returned to lesser work. The summer passed, and then in early Autumn in Hollywood, Alfred Hitchcock decided he needed something in the way of a fey girl character for an odd picture of his called “The Trouble with Harry.” “It’s a comedy,” Hitchcock liked to tell listeners, “about a corpse. Very amusing.” So he saw this test she’d made for Wallis and arranged to borrow her. He did so and the company went to Vermont for location filming. This was September of 1954, a month and year not liable to be passed over lightly by Shirley MacLaine.

She’d met Steve Parker in New York during “The Pajama Game” period. He was an actor-director and he later became her manager. Now he got up to Vermont in a hurry, and on the 17th day of that momentous month and year, they were wed.

Parker now is setting up in Japan a kind of liaison business between the Hollywood and Japanese film industries. It is, to Miss MacLaine’s way of thinking, a slightly risky procedure, “but I never said it to him. Wives who discourage their husbands should be flung to crocodiles.”

After the Hitchcock picture, she starred with Martin and Lewis in “Artists and Models,” and then in the leading feminine role in Mike Todd’s “Around the World in 80 Days.” In the interim, national Magazines and other self-appointed critics got real excited over her, as well they might, and she’d started all over again in television.

Miss MacLaine is faintly freckled, not conventionally beautiful, and not notably small or large. In fact, she stands five-six and measures 34-24-34 in the usual vertical order. Her hair, coiffed perhaps in a wind-tunnel, suggests that she may at one time or another have lost an election bet, and there is not an atom of her to betray the role of film star. She takes her work seriously, herself not at all, and indeed she is hard at work at the moment helping to form a Malibu play group, for which her financial reward will be roughly nil. Again, after the completion of “Around the World in 80 Days,” she took to the road in the play “The Sleeping Prince” instead of standing around Hollywood and Vine looking for autograph albums.

It was producer Wallis who became obsessed with the notion that Miss MacLaine had dramatic talent, director Mann who seconded this same notion, and Shirley MacLaine who prays mightily she can third it. Paramount officials say she has. Viewers of the rushes of “Hot Spell” are utterly sold on her. Nor would it appear likely they are wrong.

For the joy and surety build for her. First there was Shirley—and not so much. Then Shirley and Steve—and more and more. Then Shirley and Steve and Stephanie, and that was the breakthrough. Something happened, and everything was sunny as the beach and surf at Malibu. Like the Hal Wallis episode, it’s all sort of square—and entirely happy, like a love

story that winds up in the sunset. Only this one is just beginning.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1957