Kim Novak: “I Said ‘Yes’ To Him Too Soon!”

“It was just too soon. You can’t tell if it’s really love, that soon. You have to know one another better. And I found I wasn’t right for Roderick, nor he for me,” Kim Novak said, in an exclusive interview about her broken engagement to British newspaperman Roderick Mann. “It takes time to realize whether or not you love someone, because you don’t know how you respond to each other in all different things. I said ‘Yes’ too soon. That certainly was my mistake, and I take full blame for that. God knows I didn’t do it on purpose, but it was very wrong of me. I should have waited longer. But I was so sure . . . in the beginning,” Kim added slowly. “It seemed so right . . . and that was probably because I wanted to be in love.

“The fact that I was so lonely and miserable through the making of ‘Of Human Bondage’ made me more vulnerable, I’m sure. The picture was such an ordeal, and I was over there in Ireland all alone.

“There were so many complications on the picture, and I wasn’t to blame—contrary to what’s been said. But it looked as if I was, and everyone was blaming it all on me. And I was so frustrated and unhappy. For someone like Roderick—someone understanding, kind and sympathetic—to come along in the midst of all this foreign element—was so welcome.

“And I said ‘Yes’ before I knew how unsuited we were. There were many things. Many differences. Some of them seemed unimportant to Rod, and if it’s really right, love will surpass such things. But obviously it wasn’t that strong. Otherwise these things wouldn’t have mattered. But they did matter—terribly—”

Kim knew she would be criticized for not going ahead with wedding plans. “I can hear people saying, ‘What’s wrong with her?’ ‘Is she afraid of the responsibilities of marriage?’ But I couldn’t go ahead just to keep people from talking. I’m not going to get married for that reason.

“I’m sure many people thought that I just panicked at the last moment,” Kim went on. “But this is not true. Regardless of what anyone may think, I’m not afraid of marriage. But I am afraid of divorce—my religion, which is so important to me, would not permit me to divorce. Look how close I came to marriage, I almost jumped right into it.”

Dressed casually in a shift, Kim looked very young and vulnerable. She had driven down from Northern California in her station wagon the night before, with her Great Dane dog, Warlock, beside her. She was at her home in Bel Air for one day to keep some business appointments and discuss film offers with her business manager, Norma Kasell, and her agent. Her car was loaded down with canvases and paints. The week before she had been exploring the big tree country in Northern California, stopping to paint a scene wherever she found the inspiration. Reorienting her life. After our interview, she and her dog were to head back up the coast to her picturesque little house on a rocky cliff overlooking the Pacific, near Carmel.

“It was so good just to have someone to talk to in Ireland,” Kim said. “You see, I had no real friends there, no one I knew and trusted, no one I could just talk things out with. I went alone to Ireland without my agent, business manager, secretary, not even a hairdresser that I knew. That is how they preferred it and I wanted to cooperate, so I agreed. I was away from home, in a foreign country where all the film people not only knew each other but their livelihood and work depended upon their sticking together—the producer was the man who started Larry Harvey in films and his dear friend and defender. The cameraman and crew were hired on Larry’s previous film which he produced, directed and starred in, and therefore, might conceivably work on his future films. They couldn’t defend me even though they knew it was unfair. I understood this. I liked them and they liked me but there was nothing they could do to help the situation.

“Not that all the problems were with Larry alone,” Kim added, “they weren’t. But Larry was naturally more concerned with his own problems and because of his situation was able to have them adjusted—often at my expense. Looking back now, I’m grateful for making ‘Of Human Bondage.’ It taught me discipline. Maybe this is speaking out a little too much, but I had to accept such misunderstanding—such everything—I feel there’s nothing I couldn’t tackle now. Nothing.

“I hadn’t wanted to make ‘Bondage,’ really. I couldn’t understand why they were remaking the picture when it was done by Bette Davis—and so well. But this was to be a different interpretation, there was much pressure brought to bear on me, and I agreed to do it, finally.

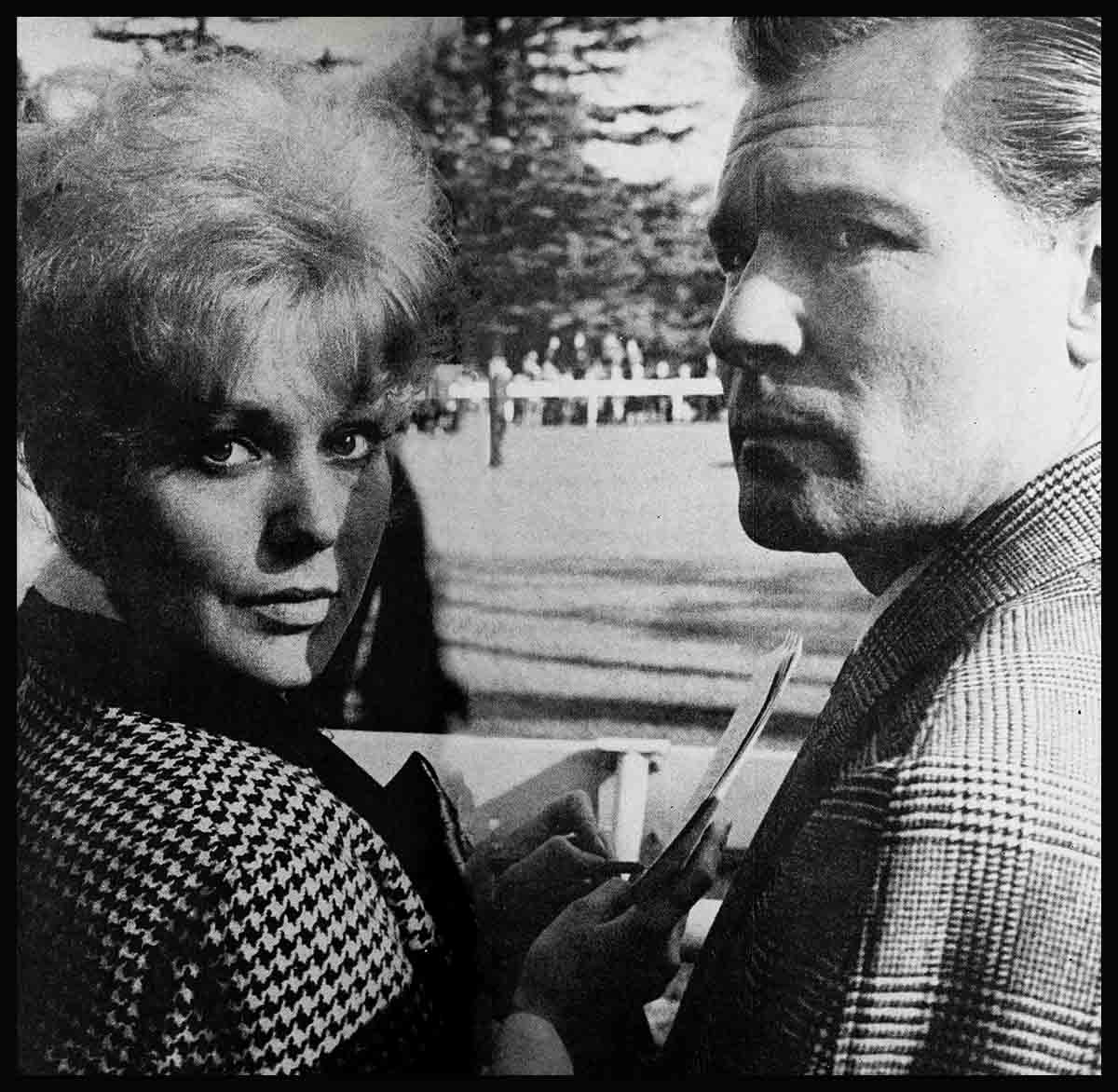

“From the beginning everything was so wrong that it got to seem that I was complaining that the whole world was wrong. It was just unbelievable! I was blamed for everything, and it wasn’t justified, I swear. I must say I’ve never had such a case of ‘Poor Little Me,’ ” Kim said with a little laugh. And into all this controversy, one day, strolled British newspaperman Roderick Mann, to interview Kim. Six feet, a handsome man with dark hair graying at the temples, and radiating charm. To Kim, at this point, he might have walked right out of King Arthur. Here was a strong shoulder and an understanding heart.

“It was so good to have someone to laugh with and have fun with, and who wasn’t connected with the film,” she said. “And I’ve always tended to feel a warmth towards writers. I love people who are sensitive and can express themselves.”

They’d originally met through their mutual friend, Cary Grant, about three or four years before, when Kim went abroad to attend the Cannes Film Festival and Roderick Mann interviewed her.

“That was a nice interview,” Kim recalls. “Friendly and warm. The English press is usually difficult and sarcastic, but Roderick was not that way.

“We did another story in London this time, before Roderick came to Ireland. And I liked him right away. He’s great fun, you know. And we shared many views in common. And his being a bachelor boy and me a bachelor girl, we had a lot of things to talk about . . . views on men and women and all.

“Then when Roderick came to Ireland, he interviewed me about marriage—why I didn’t marry or something like that. I was so surprised to learn when I talked to him that he’d researched a lot already on my views. He knew a great deal about what I thought. And we agreed about freedom in marriage, being able to remain individuals even if you did marry—things like that.”

“Roderick called the piece, ‘The Girl with the Eyes of a Poet,’ ” Kim said smilingly. “But the publication wouldn’t accept it, because they thought it was too nice, too biased. ‘Come on, now, we want the dirt about her!’ That type of thing.”

But Roderick and Kim had discovered each other. She recalled those first weeks. “Roderick writes poetry—I write poetry. We seemed to have the same interests—and there were no serious problems, like religion—or a previous marriage, since Rod had never been married before.

“I rarely go out, as you know, but I went to the horse races with Rod. Most of the time I was working so hard, I’d just see him an hour in the evening. After a day on the set of ‘Bondage,’ that was a welcome hour.” On a day off they would explore the countryside.

“You know how much I love nature,” Kim enthused. “We would take long drives into the country. There was a marvelous little place managed by this lovely old couple who were so dear—so kind to us. We could get home-cooked lunches or dinners, and we’d pick flowers in the country, take walks, and have long talks.”

They would take long Sunday walks around Kim’s hotel, just outside Bray, Ireland. The Old Conna Hotel was a former estate that had been converted into an inn. “It was such a romantic place,” Kim remembered, “with sheep and goats and horses grazing in the meadows. In the distance there was the sea. Everything that I love. But it had been like a prison to me because of the pressures of the film. Then when Rod came into it, it was like someone letting me out of the prison. Then I learned to enjoy this beautiful place.”

Here, in this lovely pastoral setting, Roderick Mann gave Kim an engagement ring, an antique emerald ring shaped like an angel with wings with little diamonds around it.

“I’m not usually given to being that impulsive—about serious things,” Kim says. “But then on the other hand, when I saw my Carmel house the first time I felt, ‘Oh this is for me!’ And I right away bought it. And that’s how I felt about Roderick at first. To think at the first signs of things being beautiful, ‘Oh yes! It’s forever.’

“But Rod knew so much more about me than I knew about him—all the things I didn’t like—all these personal feelings—and perhaps instinctively he stayed clear of many things, at first, that he knew had kept me from marriage. He knew where other men had failed in trying to possess me. So at first he probably tried not to make the same mistakes. But you can’t play a part forever. Eventually, you have to revert—and be like you really are.

“We’d talked about being married in London. But little things started happening. As soon as the film was over, I realized this wasn’t right.”

Disenchantment began to set in for Kim. Rosiness gave way to reality.

The conflicts begin

The differences began to show up—in temperament, in backgrounds, customs, countries, emotional needs. There were conflicts between Roderick’s typical British reserve and Kim’s more Bohemian volatile temperament.

“I’m an emotional person, as you know,” Kim said now. “I react emotionally to anything. My voice—my pitch—everything changes. I get excited about something, but it’s not a matter of being angry, you see. I’d get very heated talking politics. And right away Rod would take it that I was angry. ‘Why are you upset?’ he’d say.

“ ‘But I’m not upset,’ I would say.

“ ‘But you are—you’re so emotional about it.’

“ ‘You don’t understand. That’s just my way. I don’t mean anything by it.’

“ ‘Well are you always going to be like that?’ ”

And as Kim told it now, “I couldn’t say ‘no, I’ll never be that way again.’ That wouldn’t have been honest to him. But I started trying constantly to be aware of talking more calmly about everything. And I started to get very tense inside. Because I’d been holding back so much.

“Or take the fact that Rod loves a formal cultivated lawn, while I love things that grow wild and natural. That’s why I love Carmel—it changes with the sea and it’s wild and free and reckless—and that’s what I am. Rod likes the sea, but at the same time he’s thinking, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it look great to have a lawn there.’ And you know what a lawn means to me? Work. Mowing it. Routine. Well, all my life I’ve tried to get away from routine. In England we’d be riding along and Rod would say, ‘Isn’t that a fabulous lawn?’ I’d agree, but I’d point out a field where everything was growing wild and beautiful. ‘It just looks messy and dirty to me,’ he would say. And I’d say, ‘Well. I think it’s gorgeous.’ And my viewpoint on lawns, and Carmel and casual living is my viewpoint on all of my life. I believe in living and let live, I don’t want to change anything or anybody. But by the same token I don’t want to be changed, you know.”

Their differences may have seemed small, but they added up to threatening a whole way of life that Kim loves. This is Kim. Roderick Mann’s precision-thinking would seem thwarting to a free spirit like Kim. He preferred formal dining and evenings out. Kim is happier with a few close friends before an open fireplace. She’s a loner, not given to partying.

Home to Kim is a small brick house built like a miniature castle with two little turrets, that perches high on a rocky ledge jutting out over the ocean. The changing Pacific is almost part of her living room, it sprays on her bedroom window at night, rocking her to sleep. She gets her mail out of a rural mail box and has no phone.

With Roderick Mann. Kim could almost envision a changing of the Guard at her little place. Their differences were a mounting source of mutual irritation.

“Opposites may attract,” Kim says now. “And I think that’s certainly true. But I don’t go along with the theory that it’s what makes you right for one another. I put first things first. I love things to he clean and neat, but if I have an idea for a painting or a poem. I want to do it right away. And if I don’t make the bed or do the dishes, or whatever—fine!

“I can’t be that way”

“But the more I knew Rod, the more I realized that he was the kind of person where life had to be just so. Which is fine. I don’t have anything against it. I can admire someone like that. But I can’t be that way myself. And one should try to find someone who’s like that. Otherwise, eventually, we’d get on each other’s nerves.

“I didn’t expect him to change his views, but I wanted to have mine,” was Kim’s summing up. And with a thirty-eight-year-old bachelor who’s traditionally British and a decisive journalist, this represented complications.

“It was hard for Rod to accept this,” Kim went on wearily. “Men always have to prove their manhood. Any time I would challenge Rod’s thinking or have a different viewpoint, Rod took it as meaning I thought less of him as a man. That I didn’t respect his views. Well I did, and I told him I did. But you see, I think this challenged him.”

Disturbed about the uncertainties in their relationship, it was inevitable Kim would compare Roderick Mann with Richard Quine.

Kim and Dick Quine faced different problems. Heavier life-problems. Religious problems. The matter of Dick’s ex-wife and his three children. The healthy relationship with Dick’s children that was so important to Kim, that she had no chance to effect, no chance to get to know them.

Despite it all, they couldn’t seem to do without one another. When Dick was directing a picture in France, they were so lonely, Kim flew to Paris.

“I went over there hoping maybe the problems could be overcome,” Kim said. But apparently they were insoluble.

“Dick is probably the only man I’ve ever really loved,” Kim said now. “I know that, when I look back on everything. But you cannot go into marriage with such an overbalance of problems.”

With Kim and Rod there were additional problems. Where, they would live. Whether Kim would go on with her career. With Roderick’s work he couldn’t conform to Kim’s schedule. What then?

“But I think if it’s really love, things fall into place,” Kim said.

A troubled Kim flew in from London to Bel Air. Roderick Mann followed to finalize their plans—if any—and do some Hollywood assignments for his London paper. They quarreled, and Kim headed for her home in Carmel.

“I wanted to get away altogether and think.” Kim says now. “I wanted to just see how it was when I was back in my own surroundings again. See if it really was because I was lonely over there.”

Admitted—a mistake!

Back home, Kim realized she had definitely made a mistake. She returned Roderick’s ring. “I thank God I found out before there was real unhappiness,” she said. “Who needs a problem-marriage? I don’t, believe me. I don’t need this financially, nor do I need it emotionally. Some people say this is some kind of problem. On the contrary, I feel there’s a problem when you settle for someone who isn’t right for you. If you cannot find security within yourself, you can’t expect someone else to give it to you. If marriage is right, it’s a sharing of things. You both have strength and you both have weaknesses. But you’re more on the same level.

“I want to marry. I want to share, and I want to inspire. And I know some day it’s going to be right. But if I don’t find the man who’s right—if it all goes by—I’ll still have no regrets. Because believe me, I think there’s nothing lonelier than a person who’s married to the wrong mate.”

Kim says her ill-fated romance with Roderick Mann won’t make her more hesitant about marrying. “But I do know I should never rush into anything. I’ll know the right man when I find him, and I won’t let him go,” said Kim. “But I haven’t found him yet. and won’t settle for less.”

Kim gathered up her belongings: some scripts, the keys to her station wagon and her dog, for the trip back to Carmel. She added one last word:

“One begins to lose heart — in the search,” she said. “You go along and you think, ‘Oh, why isn’t something right? I’m ready. Here I am. I’m ready for a good marriage. I’m ready to share — whatever I am—and I’m wanting to. And then you can’t find the right man.

“But I don’t believe in forcing anything. If the time isn’t right, the time isn’t right. And when it is right, it will be. I’ve just go to go on believing that.”

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

Kim’s in “Of Human Bondage,” M-G-M

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments