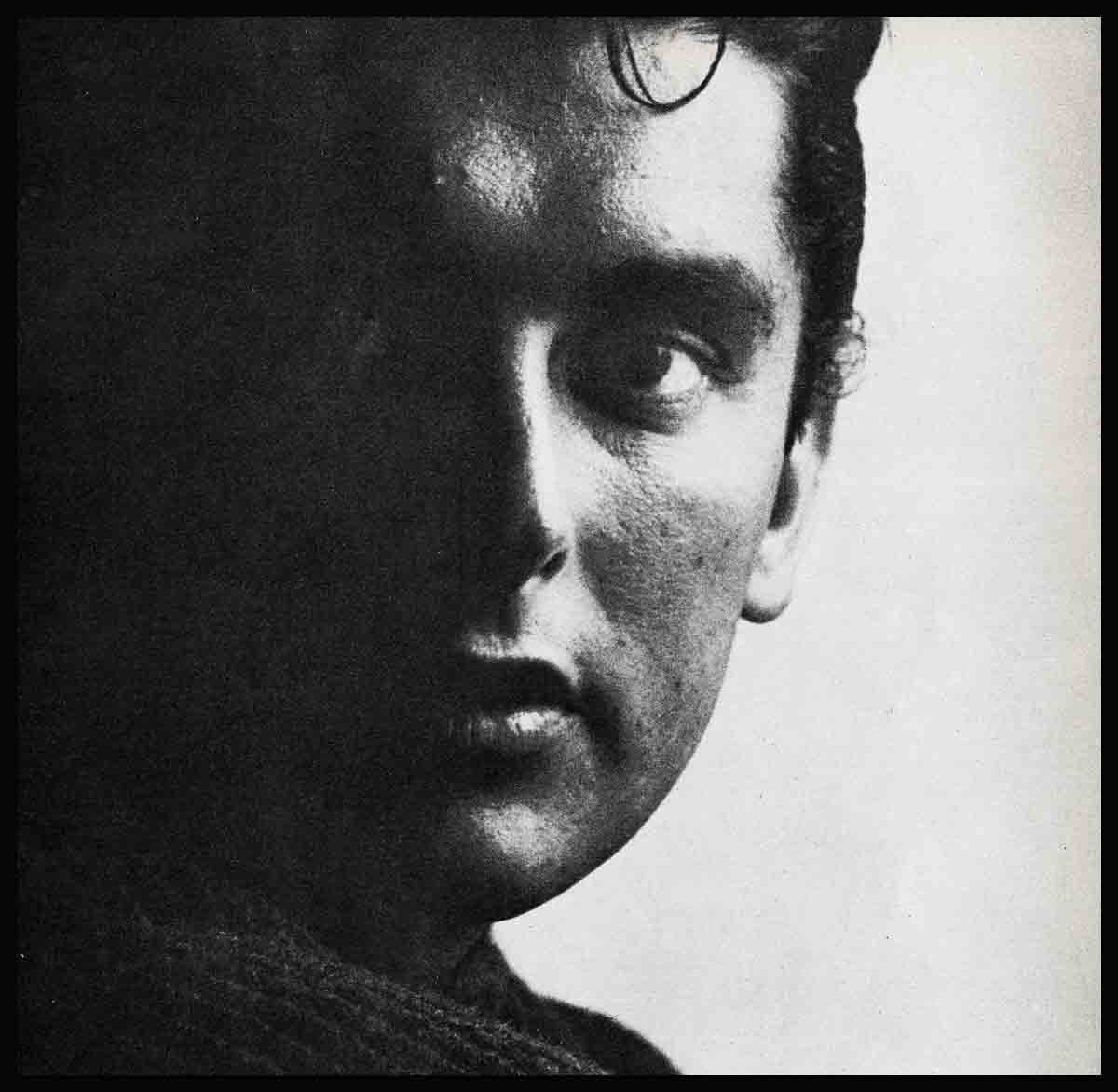

The Boy Who Couldn’t Cry—Robert Evans

Robert Evans:

The young man stepped out of the red Ferrari convertible, leaned over the side of the car and lifted out a tan pigskin suitcase. In his left hand, he balanced a tennis racket. “‘Thanks a lot.’ he said in a deep, resonant voice to the man driving the car and nodded goodbye. He then turned and walked up the canopied concrete entrance towards the hotel.

He was in his midtwenties, tall and deeply suntanned, and walked with the easy spring of a boxer. He would have looked much younger, perhaps seventeen or eighteen, if it were not for his eyes, which were black and set deeply, giving a moody disturbance to his face.

As he passed, two teenage girls, who were sitting on the veranda of the Beverly Hills Hotel, obviously waiting to see film celebrities, turned around and watched him stop at the desk and ask if his room were ready.

‘Who’s that?’ asked one Girl, nudging her friend and discreetly pointing to the young man.

Her friend, obviously expert in such matters, studied him closely. “I don’t know,” she finally admitted, adding quickly “but whoever he is, he’s got to be somebody!”

He was not: Bob Evans, at that time, two years ago, was not an actor. But there is small difference between then and now. For today, even as a much-talked about new star, little is known about Bob Evans. His friends maintain they really don’t understand him; his fans know him even less; and to his co-workers and Hollywood, he’s a puzzle. Not since Brando has a new personality been surrounded by so many rumors, so little fact and so much mystery.

“Partly, this is because of the way he looks,” says Gordon Douglas, who directed him in his latest picture, “The Fiend Who Walked the West,” which should add to the growing legend. “When you have a personality as vital and intriguing as his, rumors just naturally spring up. Bob Evans will never be able to escape unnoticed—even in a crowded room.”

At a crowded studio function in Hollywood late last summer, Bob was standing at the far end of the room, alone, when a well-known producer, who had seen Bob play the Spanish bullfighter, Romero, in “The Sun Also Rises,” spied him on the far side of the room, standing alone.

Making his way across the crowded room, he went over to him, and introduced himself and, in careful, precise English, asked: “Would you like to be introduced to some of the people here?”

Noticing Bob’s hesitation, he added quickly, “You do speak English?”

Bob said yes and they both laughed. “What are you doing in Los Angeles?” the producer asked. “Aren’t you fighting in Tiajuana this weekend?”

Thinking it was a joke, since they both were at the same studio, Bob said goodnaturedly, “No, not this weekend, but I will be fighting there next Sunday.”

“Good, good,” the producer replied. “I’d like to take my wife down to see you,” and shaking Bob’s hand, he said goodnight and walked away.

Realizing later that the producer had been serious, Bob looked for him to tell him who he really was but he had already left. The producer probably would not have believed him anyway.

Part of the reason for the mystery surrounding Bob today is that, unlike most new young actors, he’s embarrassed when he has to talk about himself. He dislikes posing for pictures and cringes when he finds his name in the columns. He has been known to hire a press agent to keep him out of print.

He is one of the most romantic young actors on the screen today. Yet, when the studio checked with him to find out why he did not attend a Hollywood premiere, he honestly admitted: “I couldn’t find anyone to go with me.” He lives in New York, in a two-and-a-half room furnished apartment that is not his own, simply because he likes the view. He can be seen frequently walking alone along Second Avenue late in the evening, guarding these walks as private and as a time to think.

It is almost as though Bob Evans were two people. One, a young sophisticated man-about-town, who looks as though he were born in a tuxedo and rides around in slinky black convertibles. This seems to be a built-in excuse, one to overshadow the other—the boy who avoids crowds, dislikes parties, insists upon being left alone and is reserved to a point of moody shyness.

It seems that to understand the mystery of the man today, one must go back to the boy of yesterday . . .

Bob Evans’ world, as a child, was the City.

He was born in New York, just thirty blocks from the Riverside Drive apartment where he lived most of his childhood. His world was bound by the Museum of Natural History on the east, the bicycle path in Central Park on the north and to the south, the sciences room at the Central Library on 42nd Street. The Drive, with its winding road and rim of lovely parks with swings and tennis courts and benches filled with young mothers and nurses and baby carriages, was a good place to grow up.

His aunt, who took care of his four-year-old brother Charles, when his mother was in the hospital, liked to tell him how his father, after hearing that he had a second son, came home, and for three hours without stopping played Chopin on the piano. His father was a dentist, but when he was a young man, he was a concert pianist and music was always part of their tightly-knit life ever since he could remember. Sunday afternoons, after dinner, while his mother cleared away the dishes, his father used to take down the brown Couperin practice book and give him a lesson.

Some afternoons, after school, he used to knock on the door of the white-haired gentleman across the corridor and sit on the stool placed by the window and listen to Mr. Rachmaninoff play. “Someday, I will teach you, too,” the famous composer and pianist said after listening to him play a Schuman march. “You have talent.” But a week after that he left on a tour and died.

“He shouldn’t spend so much time at the piano, anyway,” the neighbors would say. “He should get out in the fresh air; look how thin he is.” And his uncle, when he came to visit, would bend down and wave a finger at him, almost touching his nose, and say, “Look how big and strong Charles is.” And he would stand there, a bashful five-year-old, and bury his finger deeper into the hole in his trousers pocket, until his father would notice and come to his aid and say, “Ah, let the boy alone.”

It was true, Charles never got sick, while he was always getting a cough and rumble in his chest that kept him home in bed at least once during winter with fever.

It was the winter when he was seven that the cough did not go away and the doctor came every day and the nurse stayed all night and his mother looked worried. And even when his father brought the radio close to his bed and said he could listen to it whenever he wanted, he didn’t. He just slept.

They didn’t tell him then that the doctor did not expect him to live, but he knew, somehow, even when he was getting better, that everyone, even Charles, treated him differently and he began to feel that he was not like other kids.

He can still remember that day . . .

From their thirteenth floor apartment, with the bed pushed closer to the window, he could watch the kids rolling up a good-sized snow fort in the park across the street. It had been snowing all day, an icy snow. And because the day before and the one before that had been cold, by five that evening the streets were covered. He could hear the superintendent scraping his shovel against the sidewalk, cleaning a path to their lobby. And suddenly rebelling at having to stay in bed another minute, he pushed back the blankets with his feet, not bothering to put on his slippers or robe and rushed to the window. Opening the window, not more than five inches so the snow wouldn’t blow in, he shoved his small fist outside, scooping up a handful of cold, icy snow. Then he rolled it into a snowball.

“Are you out of bed?” he heard his mother’s voice from down the hall, and hopping off the windowseat, he ran back to bed, covered himself with the blankets and had both eyes shut tight by the time she opened the door.

“Oh, Bobby,” she said, “How will your chest clear up . . . and you opened the window.” And he watched her, with one eye shut tight, close the window and put on the guard. “You’ll never be able to go out and play . . .” she was saying, but all he could think of was his melting snowball, under the blankets.

“I hope she goes, soon,” he thought and kept his eyes closed.

“Come on, now. Stop fooling. I want to take your temperature.”

“Right, now?” he asked, forgetting his sleep.

“Yes, right now.”

And by the time his mother finished reading the thermometer, what he had feared had happened. His snowball melted and disappeared, leaving only a big wet spot on his pajama shirt. No seven-year-old ever felt more deeply wounded.

“Is Charles in, yet?” he asked, belligerently.

“No, he’s still sleighriding . . .” his mother started to stay. And then he let his quick temper flare and shouted at her. “I don’t want to stay in bed any more.” And he started to cry. “I want to be like other boys . . .” And then, feeling guilty, he apologized and said he was sorry and didn’t mean it and, yes, he would like the radio on . . . to Jack Armstrong.

He turned over in his bed, turned the dial and listened to the voice—big, booming and suspense-filled—tell him: “Tonight, we bring you the adventure of Jack Armstrong, who when we last saw him, was lost in the deep jungles of South America . . .” and leaving his mother behind on Riverside Drive and the kids outside in the snow, he escaped into the tough, double-fisted world of Jack, the all-American boy, into the world of radio he someday was going to make his own.

He fell asleep and he was Jack and when his father came in and sat down beside him on the bed and turned on the light he didn’t know, at first, where he was.

His father’s face was blurred and he blinked his eyes to bring him into focus. He looked down at the package he was holding and watched him untangle a knot in the string on the box. He was always fascinated by the way his father used his hands, especially when, sometimes, he watched him work on Saturday mornings in the office.

He wondered what was in the package. He knew it was not a toy. He didn’t like toys and wondered why his father would bring him a surprise tonight. They had an agreement; surprises were only for little boys. “Remember, Bobby,” he said, taking out a small bronze statue of a boy, “it’s better to have a few fine things like this and time to grow to love them . . .” And he began to talk about that afternoon and how mother had told him he had cried and had said he did not feel like other boys. “You should never try to be like someone else,” his father told him. “You must find out who you are and be yourself and do what you want. You should never cry, because crying means you’ve admitted defeat.”

But, that night, after dinner, his mother and father decided they would not take a vacation that summer, instead they would send Bobby away to camp. Maybe he needed more companionship.

He went to camp until he was nine. From then on, it was mutually agreed—not without effort on everybody’s part—that he was just not camp material. “If it’s possible,” his mother used to say after his three months away in the country, “he comes home thinner and greener-looking than before.”

“He’s a brilliant boy, brilliant,” the director, whom he’d never seen before, kept repeating to his father. “It’s just that he likes to sit and read all day.” But his father didn’t seem to mind too much when the director told how he went off for swims at the end of the session when most of the other boys were out of the water and how, when he lost them on a hike, he sat by the waterfall, eating his peanut butter sandwiches until they returned and picked him up on the way back.

“I guess he’s not a joiner,” his dad laughed. “We’ll have to let him hit tennis balls instead of baseballs,” but the director, who was now perspiring and who kept insisting he had worse cases than this, was not to be discouraged. On the following Wednesday, he announced: “Bob Evans you will have the lead in the camp play.”

Everybody’s parents seemed to come up that night; it was the last big event of the camp season and everybody was excited. He had the opening scene.

The prop committee had two blue bunk blankets sewed together for the curtain, and the kids who were Indians had to tie some feathers behind their ears with glued paper, but in the heat, they kept falling off so they used adhesive tape, which stuck to the skin like skin.

When the curtain went up, he was already standing in the middle of the stage, and found his parents immediately. He didn’t have much trouble finding his mother. She was sitting in the second row, a little off to the side, waving her program. He didn’t wave back. He had to listen for his cue. After a sharp hiss from the director off-stage, he was on.

Throwing out his arms in a magnificent sweep, he began: “I have . . .” and stopped. He might just as well never have learned his lines, all he could concentrate on was a buzzing around his ear. Then he felt something buzzing his knee, but he couldn’t look down, after all he was the Chief. But maybe nobody would notice, he thought, if he wiggled his knees a little, so he waited for a second until the insect alit, then, bending his legs slightly, he knocked them, one-two, together . . . and then let out a howl that brought down the curtain.

Two counselors carried him off behind the set while a third, taking out a match, struck it. He watched him bring it down closer and closer to his knee. They’re going to burn my wound out—like medicine men, he suddenly jerked his leg free and let out another howl. “Stop, don’t torture me.”

The couselors later apologized and told him they had just wanted to see what was wrong, but by that time, the doctor already found out he was stung by a wasp and the audience had left and the play never did go on.

He didn’t feel bad, but for some reason everybody kept saying, “Don’t feel bad.”

One thing was certain, that night, nobody—including his mother and father—ever thought he’d have any future on the stage. That’s why, three years later, when he was twelve and had made up his mind, he didn’t tell them about it in the beginning.

He had seen the ad on the back page of Sunday’s sport section, buried somewhere in between the want-ads and for-rent notices. He noticed it first because the school had the same name as his: Robert Evans School for Radio Acting. It promised to get you a job on radio if you took the course, so later that week, on Friday, he took a bus to the school.

The school lobby was filled with kids and he met a boy, about sixteen, who told him he’d finished the course and was now going over to NBC for an audition.

“Why not go to NBC direct?” he asked and went along with the boy.

They both filled out, in duplicate, application forms and left them with a lady at the reception desk. Ten days later, three days before the Christmas vacation, his father came to breakfast and handed him a long, white envelope from NBC with a letter asking him to come down for an audition. He thought it was a good idea then to tell his father he had decided to become an actor. But, from the way his father took it all, just looking over the top of his glasses and saying “good luck” before picking up the morning paper, he had a suspicion he didn’t take him very seriously.

That same day during study period he made up an afternoon schedule for himself for the next eight hours—one hour for tennis practice, another for judo and two hours at the library. And the following week he spent part of every afternoon in the 82nd Street & Amsterdam Avenue library, collecting Ibsen plays and copying down sections that he liked and wanted to rehearse.

He took the notes along with him when he went down for his audition, and when his turn came, he stood up and read from them as noticed the other people did, even though he knew them by heart.

“I’m a funny-looking kid,” he thought nervously waiting for the auditions to end, “I’d never hire me if I were them.” And even when the lady behind the casting desk, Miss Eleanor Kilgallen, called him over and said: “I’m going to give you a job on radio, you’ll probably regret it the rest of your life,” he didn’t quite believe her. But she gave him a script and he knew she was serious.

His only problem now was getting the sixteen dollars to join the actors union.

He rode uptown, at first trying to concentrate on the script, but he was too excited, so instead he read the advertisements, thinking how they always picked girls who want to model or do something like that for Miss Subways. When he got out at the stop near his father’s office, it was already dark and the office was crowded and he had to stand in the outer waiting room. The nurse wanted to tell his father he was there but he told her, no, it was a surprise, not to tell him. His father worked later than usual, so they had to take a cab instead of the bus home. He was glad, it turned out to be easier to talk.

“It sounds good,” his father said, when he had finished and, although his father was tired, he could tell he was pleased.

“Just so long as you’ve thought it through carefully. If that’s what you want, go right ahead. Make your own decisions, then you’ll never be sorry. And let me give you the sixteen dollars . . . No, not as a loan,” he insisted.

Even though he knew it would disappoint his parents who were so proud that he was one of the few kids to get accepted into the Bronx School of Science, he decided he had to go to a school nearer NBC. He chose the Haaren on 57th Street and Tenth Avenue, a finishing school, as some of its students liked to boast, for young delinquents to polish off such social arts as fistfighting, truancy and needling a victim. And an actor was a perfect victim.

“Where ya goin’,” singsang one of his senior classmates one day, tagging along with four or five of his black-jacketed Hellcats. “Goin’ to put on your makeup?”

“I don’t need any . . . but you sure could use some,” he flipped back as they walked to the 57th Street bus stop.

A loud giggle, quickly smothered, broke into the conversation and both boys turned to see a tiny girl, about thirteen, looking at them. “Why don’t you pick on somebody your own size?” she laughed.

“I’ll show ya . . .” the bigger boy threatened, shoving her off the curb and sending her books sprawling.

Without thinking, he grabbed the older boy by the jacket, swung him around and with his right hand, gave him a punch which knocked out three of his teeth and split his lip.

“I’m in a hurry. I can’t wait now, but meet me at NBC at two o’clock,” he said, “and let’s pick up her books.”

Not until he was on the bus did he think. What if they all ganged up on me? Beginning the next day, he started spending the hour and a half between rehearsals at the local gym, ultimately becoming a three-time finalist in amateur boxing association elimination.

That afternoon, after the show, the boy was waiting. He went home with him to explain to the boy’s mother that he had done the damage and was willing to pay. After a hot cup of chocolate, he invited the boy’s parents to his next Saturday’s show, “Let’s Pretend.” From his own earnings, for the next ten months, he paid for the dental work, not telling his father, who could have done it for nothing.

Television was the new challenge and when he was eighteen it brought him a movie offer. “Why don’t you take a rest,” his mother suggested, worried because he looked tired. “Drive down to Florida with Dad and me, before going out to Hollywood.”

Halfway down, in a little town in Georgia, they stopped for gas, and when he got out for a Coke, a sudden jab of pain in his chest bent him over and he felt as though he was partially paralyzed. After that, his Dad drove and he lay in the backseat. They stopped at a local doctor’s along the way, but the doctor said not to worry, it was indigestion, too much driving, it would go away.

It did not, and thirty-six hours later, at Palm Beach, a specialist examined him in the hotel room and said, if he had not been called in then, the boy might not have lived. His lung had collapsed and was pressing against his heart.

The next three months, he lay flat on his back, unable to rise, able only to stare at the ceiling above. It seemed then, he had lost all he had struggled for.

And then one day, after his parents and his sister Alice returned to New York, leaving him alone, the nurse brought in a small package from his father with a bronze figure of a boy. And as he lay there, he remembered a boy of seven and he remembered a lot of things he had forgotten. That one must create his own world and find his own identity and solve his own problems. And he began to learn to love the sunlight flooding in on the ceiling and to listen to the shouts of people coming home at noon and to find joy in the childish world of his five-year-old sister’s daily telephone calls. And, at eighteen, he no longer felt alone. During those three months, the boy became a man, and today, the man is called a mystery, but when you begin to understand the boy, you can begin to understand the mystery.

G. SANDS

SEE BOB IN 20TH’s “THE FIEND WHO WALKED THE WEST.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958