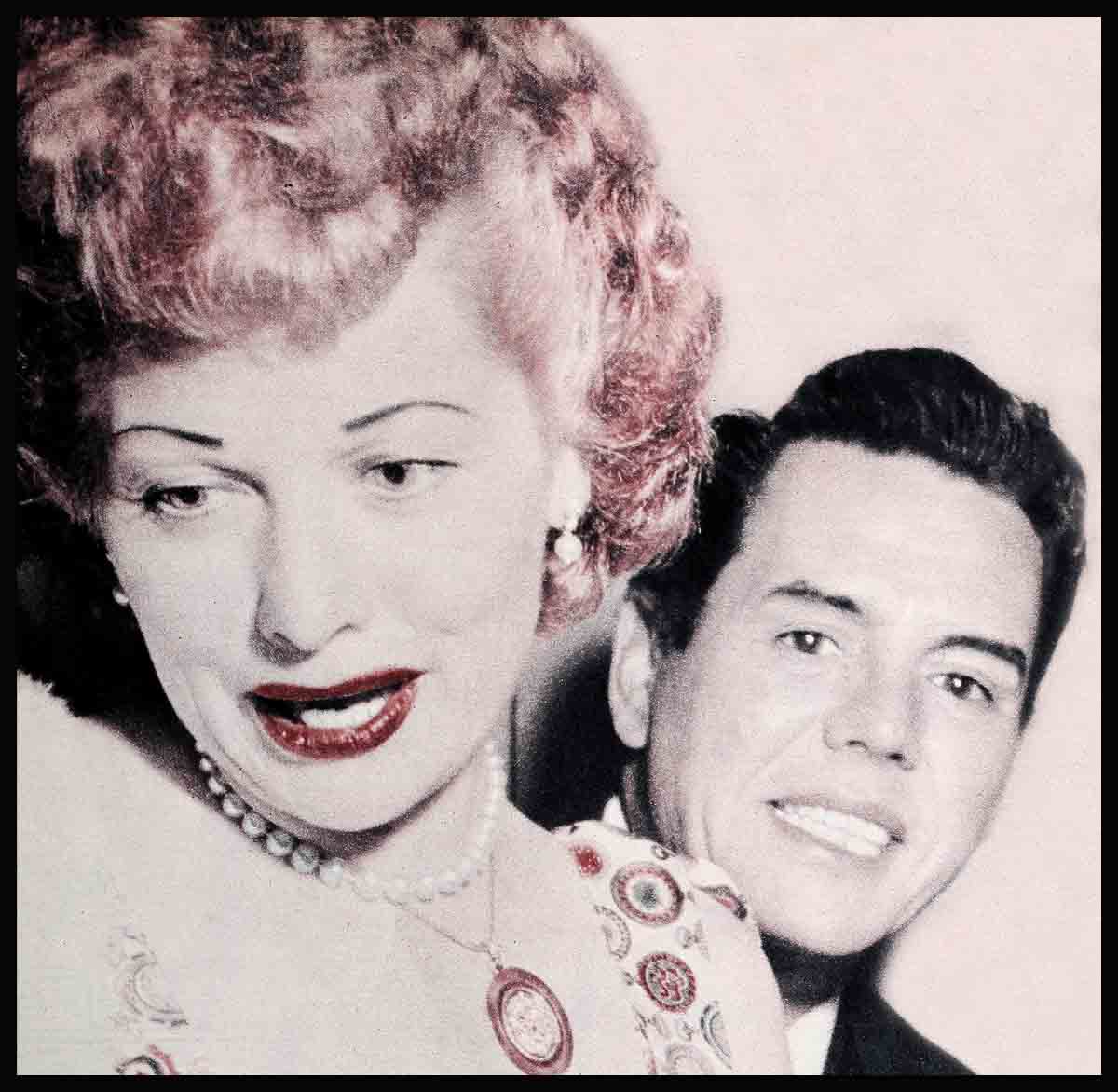

Lucille Ball: “I Just Couldn’t Take Any More”

Lucille Ball cleared her throat and said. “I’m filing tor divorce from Desi.” Instantly the assembled faces assumed expressions of shock. At this, Lucille smiled, slightly, and shook her head. “This is no surprise to anyone,” she said. “Every columnist in the country has hinted at this for months.” Someone asked: “Anything else, Lucy?” Lucille shut her eyes. Anything else? She weighed the words. “I have tried—so hard—to be fair and solve our problems. But now I find it is impossible.” She stopped. But one more thing remained to be said, one sentence not weighed, one cry that burst out on a note of anguish. Lucille Ball said:

“I’ve had it-—I just can’t take any more!” Few could look back, as they left, to see if Lucille Ball was weeping. They were so sure she was. They walked out quietly.

Why should Lucy and Desi get a divorce—with two kids. nineteen years of marriage behind them and a million dollar business empire they’ve built together? Everyone was asking that question. Together, they’re great. Apart, what have they got? A couple of unhappy children. A good chance their careers will skid. Besides, Desi’s Catholic—he’ll never marry again—and Lucy’s pushing fifty; that’s a little late to start all over with somebody else. And there’s one other thing people who know them feel. That they’re still very much in love with each other.

It was back in 1951. The cast and crew of “I love Lucy” were working late. They were hot and dirty and tired, but they were laughing. Some were bringing their hands together in delighted applause.

“Lucy, that was great!”

“This’ll be the best show yet!”

“Does anyone know what time it is? Boy, am I tired—”

From the floor on which she lay sprawled, legs out, a paint can on her head, a ladder tilted against her back, Lucille Ball managed a weary grin.

“You were tremendous, Lucy. You were—”

Through the babble of voices, another voice cut. It spoke softly, yet it seemed to slash a path of sound through the air.

“Okay—let’s take it once more,” the voice said.

There was silence. looked at each other. Then the voices rose in protest.

“Aw, Desi—”

“Desi, for Pete’s sake, we’ve been here for five hours without a breather!”

“Give us a break, Desi! We’re only human.”

“Listen, Lucy’s done that bit seven times already. She must be ready to drop. Give her a break!”

Silence. The faces turned from Desi to Lucy. The eyes watched the grin fading from the wide mouth, took note of the tired circles under the eyes.

Desi’s voice again: “What you say, Lucy—Are you too tired? Can you do it jus’ once more?”

A moment’s pause. And then Lucille Ball removed the paint can, eased away the ladder, climbed wearily to her feet. “Sure,” her voice said, determinedly bright. “I’m fine. Let’s go. What—what did I do wrong?”

It had happened so often, it became a regular occurrence. The long rehearsals. The repeats and repeats. The worried question: “You okay, Lucy?” The exhausted answer: “Sure. I’m fine.”

Why? Why did she let Desi demand what seemed impossible?

The answer was complex, but not hard to find. It dated back to the day when Lucille met Desi Arnaz, a Cuban bandleader who was to work in one of her movies. She was a star, then, and comparatively, he was no one—but he wore like a garment the Cuban air of being a man among men, of male pride, of calm, masculine assurance. In his home, one knew at a glance, there would be no question of who ruled: the man did. Gently, of course, kindly, loving, indulgently—but unquestionably.

To Lucille, this was very wonderful. She had seen so many Hollywood marriages in which the woman, the big star, dominated the home. She herself had worked since she was a young girl, had had to fight her way to the top with every bit of strength and endurance she had. But, with a man like Desi, a woman could build a real love, a real marriage, secure in the knowledge that her man would take care of her, and do it well.

There were those who said that Lucille Ball didn’t know what she was doing when she married Desi Arnaz. But they were wrong. She knew exactly what she was doing.

She was taking her rightful place in the scheme of things.

. . . But she was in love

There was no reason to give up her career. Desi, for all his comparative obscurity, had a flourishing career of his own, made almost $100,000 a year—but had to be on the road with his band a great deal. While he was gone, she would make movies. She loved her work, her success, her fame. She’d worked hard for it. And since Desi didn’t object—

So Desi went back on tour with his band. Lucy went back to making movies. Desi made money; Lucy made money. They made so much, they could easily afford the thousands of dollars spent on phone calls keeping in touch with each other, because they were never—literally never—together.

It was very profitable, but it was not a marriage.

After a while, they knew it wasn’t working. Finally, Lucy took a desperate step. She filed for divorce. She was awarded a decree. For a few weeks, she held onto it, telling herself that she had done the right thing, the only thing. Then, she went back to Desi.

They were more in love than ever, then, and very determined to make their marriage work. By now, they knew how it had to be done. One of them would have to give up a career.

It would have been easy for Desi to have been the one. He could have become Lucy’s manager. Or gotten, through her, parts in her movies. Or refused to accept anything but California dates for his band. In most movie-star homes, that would have been the solution.

Not in Lucy’s.

Without making headlines about it, she quietly gave up most of her own work.

It was, people said, a mad thing to do. She would never be happy without working. And what would they live on? The demand for South American music was not what it had once been.

“We’ll manage,” Lucy said. “I’m not retiring altogether. I’ll do a radio show—or something.” She smiled.

She was happy. That’s all that mattered.

One of the predictions did come true. South American music was on its way out. The Arnaz income dwindled greatly.

Lucy went right on being happy. She and Desi were together; all was right with the world.

And then she woke up to the fact that, although she had what she wanted out of life, her husband did not.

Desi Arnaz was, as she knew, a strong man. It began to be clear to her that he needed far more scope for his strength than a failing band provided.

He needed work worthy of his talents.

So, when he came to her one day and said, “I have an idea. A situation comedy for television. We’ll star in it together, and I will also have a hand in producing, directing. Who do you think, honey?”

She looked at his eyes, alive with eagerness, she heard the hope and confidence in his voice.

“Sounds good,” she said.

It meant giving up so much. Their privacy. Their hard-won hours together. It meant risking their diminishing money and their reputations on one throw of the dice.

She would have risked much more than that to give Desi his chance. But there was one thing, as they went ahead with “I Love Lucy,” that she hadn’t counted on.

She had not completely realized how extraordinary Desi really was.

Other people thought of him as only a glorified bongo-player. Lucy knew his talent for attending to details, the agility of his mind in a tight spot, his originality, his perfectionism when it counted most.

She did not know to what extent her husband was a living dynamo of thought, energy, ambition. Desi, behind a camera, saw what other trained eyes missed, and set out to correct it mercilessly. Desi, at a script conference, rejected line after line at which other people giggled—till he found the one that made them roar. Desi, at rehearsal, switched from actor to director or cameraman with unflagging energy, taking no breaks, pausing for nothing, sparing himself for not a moment. What he didn’t already know, he learned. What he learned, he mastered.

Those who had laughed at him, now looked at him with awe.

Lucy’s own admiration increased.

But, of course, all of Desi’s incredible activity would be wasted unless the star of the show also met his exacting standards. The star was Lucy.

She would meet them.

She would not let him down.

Only—

She had never known she could be so tired.

That there could be so few hours in a day.

So little time to rest. Sometimes, no time.

Of course, that couldn’t be helped now. But later, when everything had really jelled, then, surely, Desi would relax. Soon—very soon—

But now—

“You okay for one more run-through, honey?”

“Of course, Desi. Let’s go.”

The end of a beginning

It had all come true.

All the dreams. All the hopes. risks, schemes, plans had worked.

The world had learned that Desi Arnaz was someone very special. Someone who had insane ideas—and made them work.

He had insisted on investing their money in the insane extravagance of filming their show, instead of doing it live. All he’d asked, in return, was the rights to any profits from later re-runs of those films. Everyone knew that would come to nothing.

Now those re-runs are being shown all over the world.

He had invested thousands, and made millions.

He had risked catastrophe by plunging them into debt to buy the studio for which they had once worked—RKO. Everyone knew it was foolish to own and rent studios to other people, when you were getting along fine being a tenant yourself.

Now TV companies of all sorts were asking—and paying—for the use of the Desilu facilities.

He had invested millions, multi-millions.

He had developed new camera techniques for filming his shows.

His directorial skills were famous.

His judgment of audience response was phenomenal.

His professional opinion was sought by such old pros as Arthur Godfrey.

It had all come true. Only—

Somehow, they didn’t seem to have slowed down.

Rehearsals still lasted till late at night. Lucy still did her scenes over and over, till they were not merely as good as last week’s, but better.

And Desi was much too busy to sit back and enjoy his success.

There were the nights when Lucy went home, alone, because Desi was busy at the studio, editing film—or conferring with the writers—or directing the set construction.

There were the days when he was at RKO from breakfast till dinner, making sure that the sound-stages were ready for other people’s use.

The lunches with sponsors and ad men.

The dinners with people who needed his advice.

The evenings with business acquaintances.

And, somehow, never just the two of them alone.

“Desi, let’s call and say we can’t go tonight. I’ll fix dinner for us and we’ll just stay home with the kids.”

“Aw, sweetheart, you know we can’ do that. They’re friends. They’ll be disappointed.”

“They’re business, not friends!”

“You don’ like them? But I thought you like’ them so much!”

“I do like them. But—I love you. I want to stay home with you—”

“I love you too, honey. And tomorrow night we’ll stay home—jus’ you an’ me. It will be wonderful, huh? But tonight, we got to go out—jus’ this once more—”

“All right. I know. All right.”

They went out.

And when tomorrow night came, there was an emergency on stage three. The night after that, rehearsals. Then the how. Then—it went on and on and on. . . .

There so seldom seemed to be time for “tomorrow night.”

Sometimes it seemed that Desi didn’t want it to come.

It was as if the success of their work had liberated some hidden source of energy in him—something that would not let him slow down. At the end of a day that would have sent other men staggering home to bed, Desi was more alive than he had been that very same morning. Work, Lucille told herself, was a stimulant to Desi. The more he did, the more he was ready to do. And if there was no work, then that fantastic energy had to be burned up some other way. If rehearsals had been good, why not go out and celebrate? If bad, why not go out and forget it?

“Look. You go without me tonight, darling. I’ll just spoil your fun by conking out before you’re ready to come home. I know I will.”

“No. No. I won’ go without you. I wouldn’ enjoy it.”

“Sure you will. You know how you’ve looked forward to this party. But I have a headache—it’s silly for me to go. I’ll tell you what. Wake me up when you get home and tell me all about it.”

“Well. Maybe. Jus’ this once. If you’re sure it’s okay.”

She began to spend more and more evenings alone at home.

They grew longer and darker every time.

And then 1959

The phone rang. It rang and rang, shrill in the silent house. Lucille Ball heard it, finally, and groped her way to a light switch. Early morning. Desi had not come in, yet. If this was another emergency call from Desilu, what would she say? I’m sorry, I don’t know where he is, try Las Vegas, try anywhere but here—he’s so seldom here!

She picked up the phone.

“Mrs. Arnaz?”

“Yes?”

“I’m sorry to disturb you, ma’am. This is the police.”

“Desi! Is he all right?”

“He’s not hurt. We picked him up. Too much to drink—”

How do you measure heartbreak?

What do you do when a dream comes true—and turns out to be a nightmare?

It was not the only time Desi’s name appeared in the papers, after an encounter with the police.

The “Lucy” shows went on, still popular.

The awards poured in. Money poured in. Desilu boomed.

At home, night after night, Lucille sat and wondered where the joy, she should have felt in these things, had gone.

Out, night after night, Desi tried to forget that in gaining the world, he had somehow lost his marriage.

Which of them suffered more, no one knew.

No one knew much about the situation at all.

They were such expert comedians, the Arnazes, that it was no great problem to play one last joke, to say there was nothing wrong, to smile brightly for the cameras.

But there were slips.

There was Lucy, saying to a reporter, “I think Desi plans to go to Europe this fall.”

I think—?

There was Desi, photographed at Las Vegas for the dozenth time, without Lucy—caught looking somehow lost and alone, a little less than happy.

There was the night a friend phoned Lucille and heard her say wistfully, “It sounds like you have people over there—”

“I do. Just a few friends. We’re going to fix dinner.”

“You are? It sounds . . . it sounds wonderful.”

“Lucy—would you like to come over? We’d love to have you—I had no idea you weren’t doing anything.”

“Would fifteen minutes be too soon?” asked Lucille Ball.

She was there in ten. She brought an apron and helped with the cooking; she chattered and laughed, and if her eyes never smiled, at least her lips did. Hours later, someone said: “For heavens’ sake, your show is on, Lucy!”

She looked up sharply, the smiles gone. “Is it? Oh. Well—”

There was an embarrassed pause. “Would you . . . should we turn it on?”

The pause lengthened. “I . . . yes. Desi asked me to watch it, so—”

They put it on. It was a good show. Everybody laughed a lot. Everybody, except Lucille.

At the door, her hostess said goodnight. “I’m so sorry you missed the first half of your show.”

Lucille looked at her. not. Sometimes—”

“Sometimes?”

“Nothing,” she said. “I had a very good time. Thank you.”

And she was gone.

To many rumors

The joke was almost over.

There were too many rumors now.

Still, sometimes they tried to stop them.

When they heard that they had not “appeared together in public for almost a year,” they took the children and went out to dinner together. The columnists dutifully reported that the Arnaz family ate heartily and smiled a lot.

When Desi, alone in Europe, heard that he was not expected to go back to Lucille, he told newsmen it was nonsense; of course he was going home. The reporters told their readers that Desi had bought tons of toys for the children, gallons of perfume for Lucy.

When Lucy, in Hollywood alone, went to a premiere with an escort who was not her husband, photographers stated, firmly, that he was an old friend of the family, subbing for Desi.

When word spread that Desilu was up for sale, Lucy managed one of her famous, wide-mouthed smiles. “I’m sure it’s not true. I don’t know much about the business end, but I am a vice-president. I think they’d have to tell me if they were selling!”

Brave tries, all.

But there were some stories there was no use denying.

One said that they had been secretly living apart for a year. True or false? It only depended on what you meant by “apart.” Another said that Lucy was going to do a Broadway show—and that Desi would not go East with her.

Still another said that the cast and crew had wept at the last filming of an “I Love Lucy” show—because they knew that more than a great television legend was coming to an end.

The rumors stopped on the day when Lucy cried out to the reporters:

“I just couldn’t take any more!”

Now, there were facts—not rumors.

The fact that the divorce would be “amicable,” with the accusation of mental cruelty a legal formality only.

The fact that the children would not be made victims of a custody battle, but would be in joint custody of both parents, with Desi able to see them any time he wished.

“Lucy and I had a difficult time explaining our divorce to our children,” Desi said. “Finally I said: ‘A divorce is like getting a piece of paper from a judge.’ Little Desi was silent, then came up with: ‘Well, when you get it, can you give the divorce back?’ ”

That was a child’s question. Everything else was a fact.

The fact that Lucy had rented a huge New York apartment in the hope of a Broadway hit.

The fact that Desilu was not for sale, and was still in the talented hands of Desi.

The fact that the marriage was over.

“Why?” the reporter asked again. “What is it she can’t take any more? They’re still in love with each other. They’re not even angry!”

No, they were not angry. How could you be angry at something that was nobody’s fault? At a dream-come-true—gone wrong? At a man who had too much talent, too much energy? You don’t get angry at such things.

You don’t even fall out of love.

The only thing that happens is that a marriage ends.

It happens when, at last, someone can’t take any more.

THE END

BY CHARLOTTE DINTER

BE SURE TO CATCH LUCY AND DESI IN THE “I LOVE LUCY” RERUNS ON YOUR LOCAL STATION. SEE THE “DESILU PLAYHOUSE” ONCE A MONTH ON FRIDAYS, FROM 9-10 P.M. EDT, OVER CBS-TV.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1960