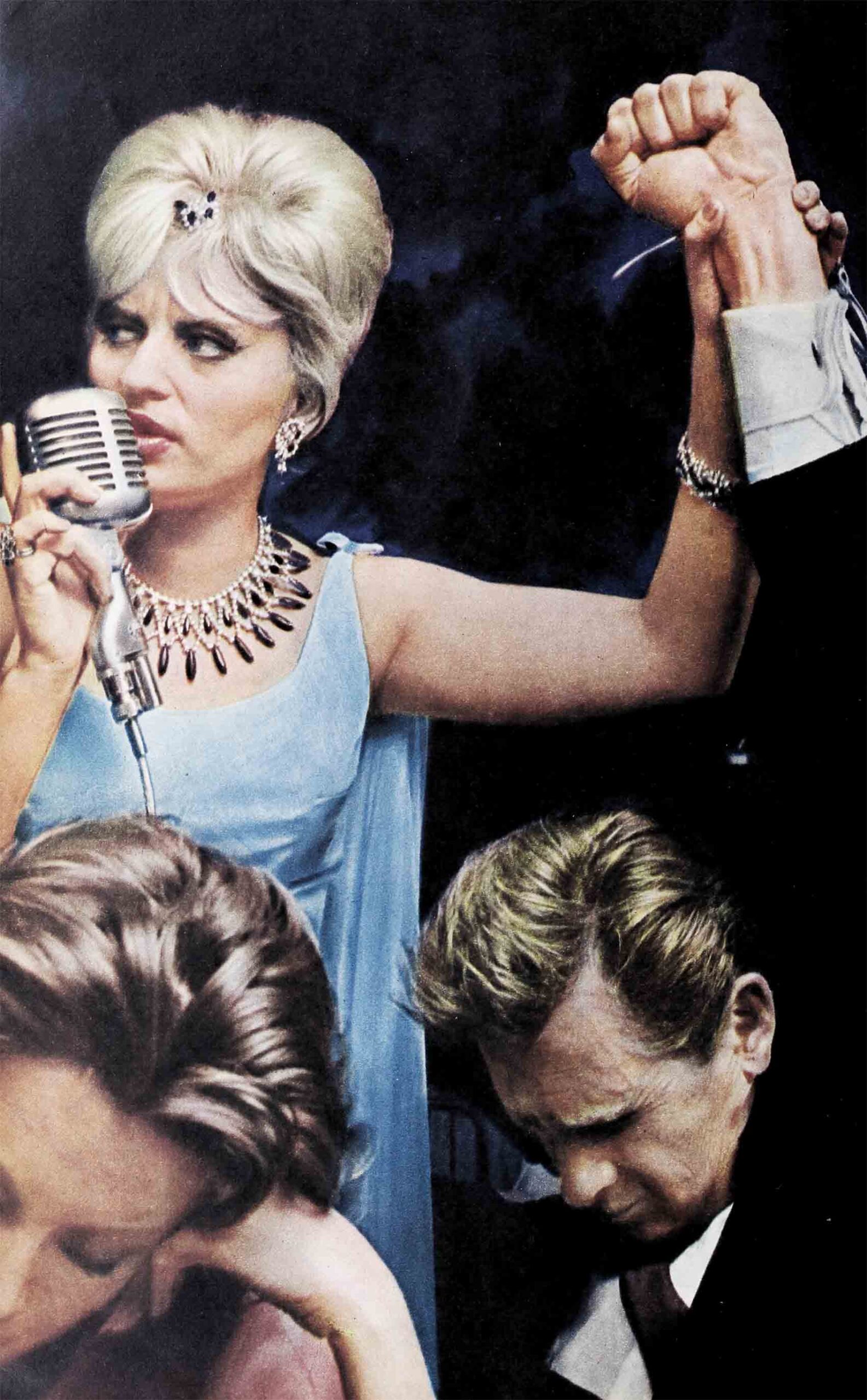

“I Hypnotize The Stars!”

If Hollywood’s voluptuous blond brain-charming hypnotist, Pat Collins, had been around a couple of hundred years ago, she would have been burned at the stake with thousands of hysterical onlookers screaming in joy and salvation at her painful passing. And there were times in her early years when Pat herself would have preferred death, even at the stake, to life.

Because this was her life: She was disowned by her father when she was born; abandoned by her mother before she was a year old; raised as an unwanted child in a Chicago orphanage until she was five: scorned, used and abused by a parade of faithless foster parents until she was twelve; married and divorced at sixteen and paralyzed from the waist down at seventeen.

Today she is one of the most beautiful and glamorous women in show business (she looks like a blond Sophia Loren), and is a fantastic smash as a hypnotist. To Pat, this is all a miracle of miracles, after such a start.

“I have reserved an empty space in my mind and heart for my father.” says Pat. “I never knew him. I wouldn’t know him today. I don’t know why he refused to love me when I was born. I don’t know what happened between him and my mother, because my mother didn’t keep me long enough to let me find out. She dumped me at the door of an orphanage when I was a baby. They raised me.

No one wanted her

“My memory of the orphan home is vague. I faintly remember times when I was brought before pleasant adults who looked me over and then turned away. I was always sad.

The mood to talk about her childhood is rare with Pat. “Things are so great for me now,” she said, “that I hate to dissipate the present with the past—I can’t remember, really remember, a happy moment as a girl. All I recall is a swarm of inattentive fathers and a band of thin-lipped mothers whose reasons for taking me into their homes I’ll never know.

“When I was twelve,” Pat continued, “I finally came into a home where my foster parents turned out to be kind and understanding, and I soon realized that their affection for me was genuine. Believe me, by then I knew the difference.

“A year later I fell in love. These people had a boy two years older than I, and he’d been around all the time, but one afternoon, just before my fourteenth birthday, I looked at him. Before I turned away I was in love. I think what happened was that these parents had given me something I’d never known before—their love. Then, and only then, was I able to love someone myself. It sounds strange, but I’m sure that was it, and I couldn’t help myself. I hid my feelings for more than a year—it was strictly a brother-sister, buddy-buddy relationship. But then he told me he loved me. You can imagine what that did to me!

“Suddenly, in all this ecstasy, we realized what a problem it was going to be. I mean, being in love and living in the same house with the same parents. I told my foster parents about it. They were very upset. They said we were too young to really experience a lasting love. They were right, but their advice didn’t help. Soon after my sixteenth birthday we eloped. We lied about our ages and got married.

“I don’t think we were together more than a month when we understood the mistake we had made. We blamed everything for our unhappiness except the real cause—that we simply weren’t mature enough to cope with the responsibilities of marriage. But two months later I discovered I was pregnant.”

Oddly enough. Pat was happy about the coming baby. For all the unhappiness she had gone through with her teenaged husband, she convinced herself that something good had come of their love after all. She told the boy the baby would not keep them tied together, she’d manage, somehow, without him.

Pat had her baby, and in a few months, a divorce.

“I thought things would be easier in some ways,” Pat said. “I was certain the Fates couldn’t possibly be unkind to a young girl who loved her baby. But the real shock of my life was ahead of me.

“I said earlier that I could not remember any happy moments as a girl. But there were times when I tried to understand what happiness was. Those were the times when I went to the movies. I scrounged pennies to make the price of admission and to this day I don’t regret it. For up there on the screen were my joys, my excitements, my loves and that particular kind of emotional misery every woman enjoys, although we hate to admit it.

“The stars? I loved them all, they represented fulfillment, quick dreams. And more—the movies taught me the rule I’ve tried to live by: Every single thing you really want in life seems improbable, yet none of them are impossible.

“If anyone ever doubts that, all they have to do is look at me.

“I was seventeen, my daughter was just learning to walk. I was on my way to an audition as a singer, when my own legs collapsed under me.”

When Pat came to, in the hospital, she learned that she was paralyzed from the waist down.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she remembers. “I thought it was a bad dream, that I had fallen into some movie and I would awaken soon in the middle of it. But it was all very real. I was in a hospital bed, and my legs wouldn’t move. A parade of doctors examined me. Nothing organically wrong, they decided—a matter of nerves suddenly and mysteriously gone dead.

“God punished me . . .”

“But they were wrong. I knew what the reason was. I was being punished. God struck me down for some terrible thing I had done in my life. For weeks I lay in bed reliving my life as far back as I could remember, trying to recall anything I had said or done that warranted such vengeance. I couldn’t think of a thing except once I had found a dollar bill in the street and hadn’t worked very hard to find the owner.

“At the end of two months I was cried out. Doctors probed my legs and looked seriously at each other and shook their heads with a solemnity that terrified me. I might as well have been dead, because the one hope I had was gone. You see, the movies had given me something else. An ambition. But such an impossible ambition that I was embarrassed to even think about it, let alone tell anyone.

“I wanted to be an entertainer. I wanted to sing. My voice wasn’t bad and my figure had filled out in the right places and I had come into my teens with one asset that’s hard to believe—a sense of humor. I loved to laugh and I loved to see others laugh. That was my plan. If I couldn’t sing well enough to be a professional, at least I could learn to be funny.

“And now I was the butt of the biggest joke of all: I was seventeen years old. a female paraplegic with no hope of recovery, no money, no relatives, no husband, and a baby girl barely a year old.”

She tried, heartbreakingly, to prepare for life as an invalid. The doctors and nurses spoke softly of hope, but their kind words carried awful overtones of futility. Pat was so desperate that she hated to wake up in the morning.

“And then one morning I did look up,” Pat says, “and saw a smiling intern. He wasn’t handsome, but he had that dedicated young-doctor look. And I thought to myself, here’s another one who’s going to inject me with hope because he thinks lie’s smarter than everyone else.

“I stared back at him as he said, ‘Good morning. Miss Collins.’ The smile on his face was disarming. Because in a flash I saw: the real strength of this man was not in his smile or his rugged appearance or his bedside manner. His power was in his eyes and his voice.”

The doctor told Pat he was from the Illinois Research Hospital. He had been given permission to treat her, if she agreed.

“However, I must warn you,” the doctor pointed out, “that my treatment will be unusual. I want to use hypnosis to help you walk again.”

Hypnosis? Pat didn’t understand. The doctor explained. “It’s been successful in some cases such as yours. I’ll put it very simply: I believe that the nerves which allow you to move the muscles that enable you to walk are not dead, but frozen. I think hypnosis may thaw them out. I make no promises. But there will be no pain. As a matter of fact, you may even find it invigorating. Will you trust me?”

Pat smiles when she recalls her answer. “I said, ‘Yes, doctor, of course.’ Yet in my mind I had already decided to refuse him. I dreaded another hope, another failure, deeper despair. But I guess he had already hypnotized me against refusing!”

“For three weeks straight he came every day. Sessions after session. Nothing happened, except I enjoyed his company and the treatment.

“I had always thought, as most people do, that hypnosis involved a trance, and you never knew what you were doing until someone told you about it later. Not true. I was conscious every second, the only real sensation I felt was a slight lightness, of being less dragged down by the weight of hopelessness. That was good. “But with my legs—nothing. I marveled at his hope. I had none of my own.

The miracle happened

“And then one day in the middle of the fourth week it happened. At the doctor’s suggestion, and without even thinking—I moved one of my legs. I couldn’t believe it! I thought it was just a spasm. I tried it again and the leg moved again. I could have screamed with excitement. But instead, for the first time in months, I cried.”

From that point, Pat’s recovery was phenomenal. In five days she was on her feet and walking.

Once out of the hospital, Pat could not escape the fascination of hypnotism. Sacrificing the time and money she could have spent on furthering her show business career, she enrolled at the Illinois Institute of Hypnosis. There she studied and worked with psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians and her fellow students.

“But I had to have money to pay for my tuition and books and to support myself and my baby. I sang in small night clubs around Chicago—thank heavens there are so many. I was learning show business at night and going to school in the day. Oddly enough, hypnotism had not only given me back my life, but with it a new strange sense of confidence. “I didn’t think I was the best singer in the world, none of that nonsense, but I now had a feeling of competency, a sureness about what I was doing and wanted to be.

“I’d like to point out, however, that under hypnosis you will never do what you know is wrong or don’t want to do. You will only do those things which you haven’t had the nerve to do. Many people who felt that they “might” do something improper are actually disappointed to find out that they are not nearly as subconsciously “wicked” as they think. The point is, no hypnotist can make you do anything that is contrary to your sense of what is right.

“For nearly eight years I went on leading a double life. My work and study during the day, my profession as a singer-comedienne at night.

“Then, a few years ago, two fellow performers, Phil Ford and Mimi Hines—two of the funniest people alive—suggested that if I could use hypnotism as an entertainer and stayed within the bounds of good taste, it might be a very unusual act. I decided to try it.”

But not even Pat’s agents and managers were prepared for the sensational effects of her hard-won ability to hypnotize. She was a smash from coast to coast. Everywhere she was booked, her performances packed the clubs. “I haven’t had so much fun in a night club in ten years,” audiences kept saying, marveling at it all.

They’ll “believe” anything

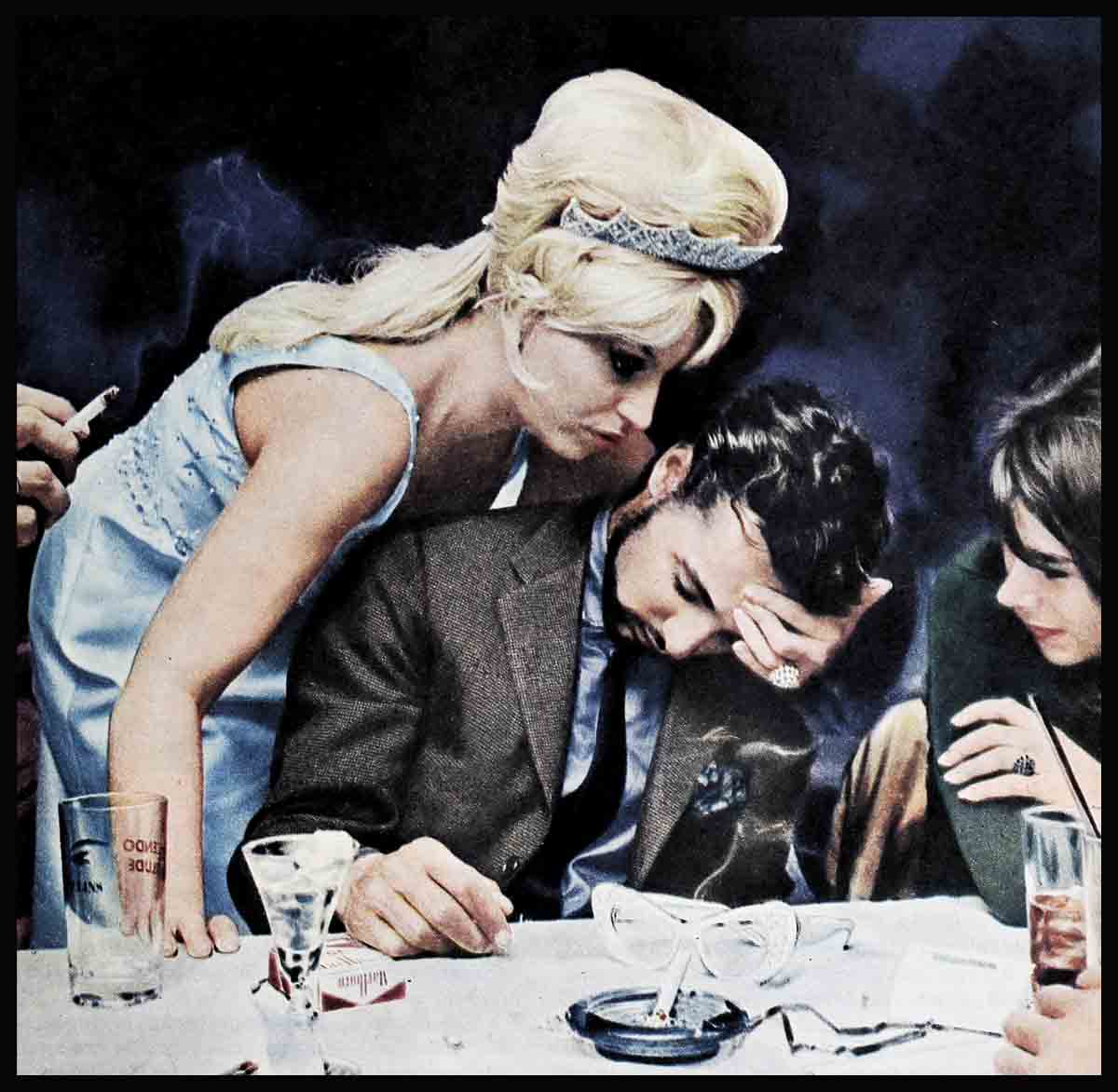

Pat’s performances in Hollywood often draw as many name stars as a premiere.

Lloyd Bridges, “went under” for a glittering audience at the Sunset Strip Interlude, where Pat appears when in Hollywood. For ten minutes Bridges happily “swam” around the tables, fully convinced he was underwater with the mermaids.

One of the most amazing reactions of Pat’s power occurred when Sal Mineo asked her, before the hypnosis, to try to get him to play the drums which he had not touched since he made his sensational appearance as a jazz drummer in “The Gene Krupa Story,” several years ago. Sure enough, once under Pat’s spell. Sal sat down at the drums and wowed the audience with a performance he could not repeat later when he was no longer under the Collins influence.

Cary Grant is a frequent member of Pat’s audience.

“But,” says Pat, “he goes under and just sits at the table and does nothing except relax. Isn’t that a shame?”

When Jill St. John “goes under,” she can’t wait to do a very sexy dance which many viewers say is strictly stripper stuff, although Jill sheds nothing but her inhibitions.

Tuesday Weld, under hypnosis, runs or dances. Even in a trance she’s a rebel. The night she came on stage, with two other girls, Pat told them all to do a Cleopatra like swing and sway. The three started. Tuesday stopped, her eyes on fire. She then pushed both the other dancers off the stage, mumbling, “When I dance, nobody else dances.”

Linda Christian, fresh from her highly publicized spat with Glenn Ford, was made to believe that a man sitting next to her was Glenn. Linda turned and told “Glenn” in no uncertain terms, that he was “a rat.”

Pat’s “power” can also enable a person to become so rigid that his body can bridge the backs of two widely spaced chairs—as she did to Steve Allen.

Marlon Brando accused Pat of being a fraud, but a ringsider vowed it was Brando who was the fraud. “He claims to be an actor,” said the patron. It brought down the house.

One producer has seen Pat perform more than twenty times. She feels there’s a humorous irony in all this. “As a kid I went to the movies and let the stars hypnotize me. Now I hypnotize them!”

And though she is a ravishing blonde, women like Pat. Hundreds have taken an almost confessional approach when they meet her. They spill their hearts out.

“And in nearly every case,” Pat observed, “they end up discussing sex. and one sex problem in particular: their difficulty in relaxing during relations with their husbands or sweethearts. A conclusion from me would hardly be scientific, but from the number of women who have sought my advice on sexual happiness. I wouldn’t be surprised if most women in the United States aren’t deathly afraid of sex. It’s amazing how few, even mothers of four and five children, really understand that sex relations between a husband and a wife are perfectly legitimate. But, of course, I have to tell them that I cannot help them, and only a psychiatrist can relieve them of this unhappy anxiety.”

What about Pat’s love life?

“I haven’t zeroed in on one particular man yet,” she smiled. “But it will happen, and I can hardly wait.”

“You know,” she added, “I think back to those terrible days when I lay in that bed unable to walk, and I remember it was so easy to think of my paralysis as a punishment. Now I don’t know.

“They say the ways of God are many, wondrous and wise. I wonder if that was one of them. That somehow I had been taught to love life by first being made to be afraid of it.”

THE END

—BY ALAN SOMERS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments