Homecoming—Esther Williams & Ben Gage

Relax, New England. Take it easy, Boston, Providence, Worcester, Bridgeport and New Haven. And you Yales and Harvards—you can catch your breath now. Miss Esther Williams, the one-girl invasion, has completed her personal appearance tour with This Time For Keeps, and is back in Hollywood.

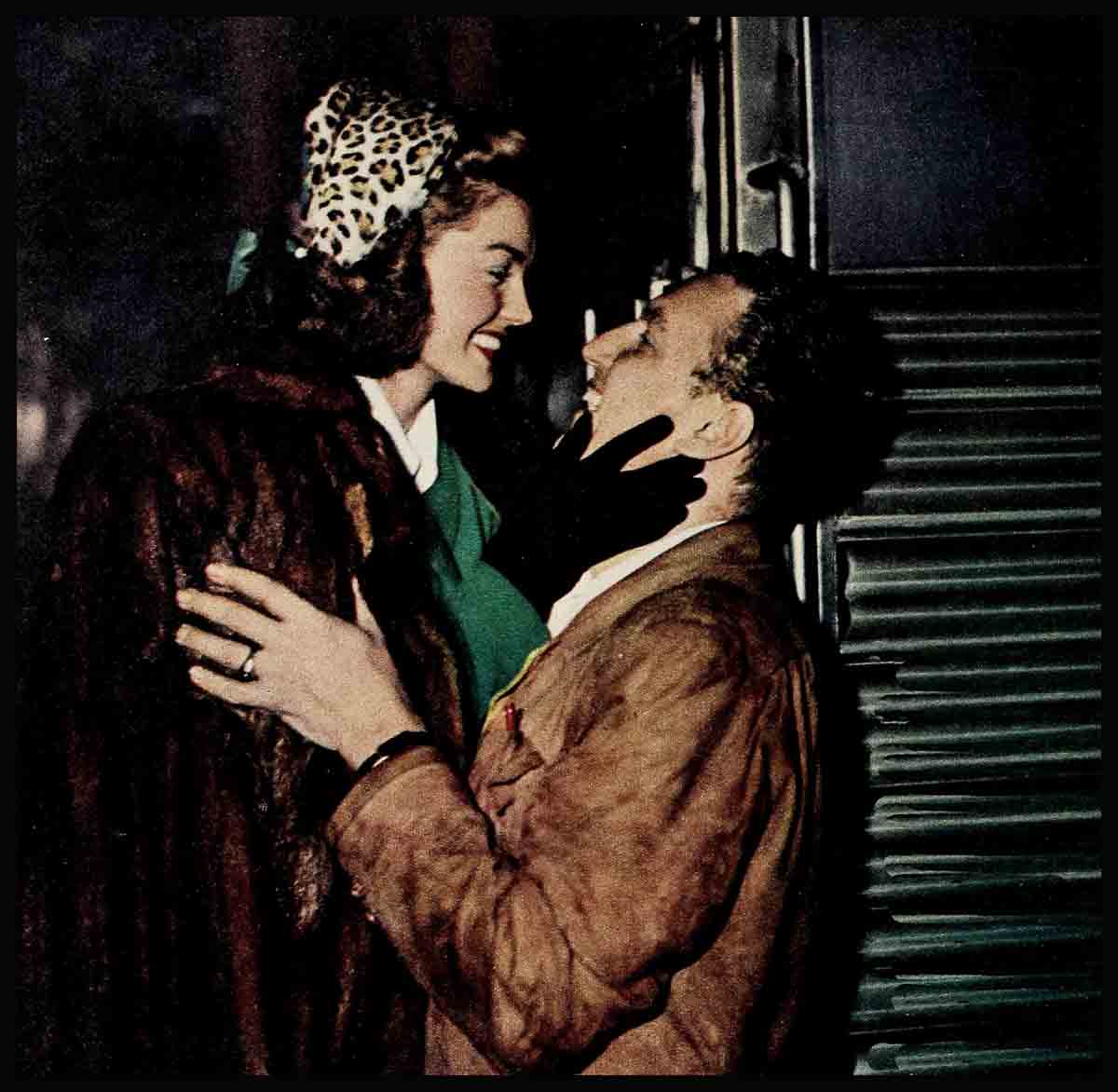

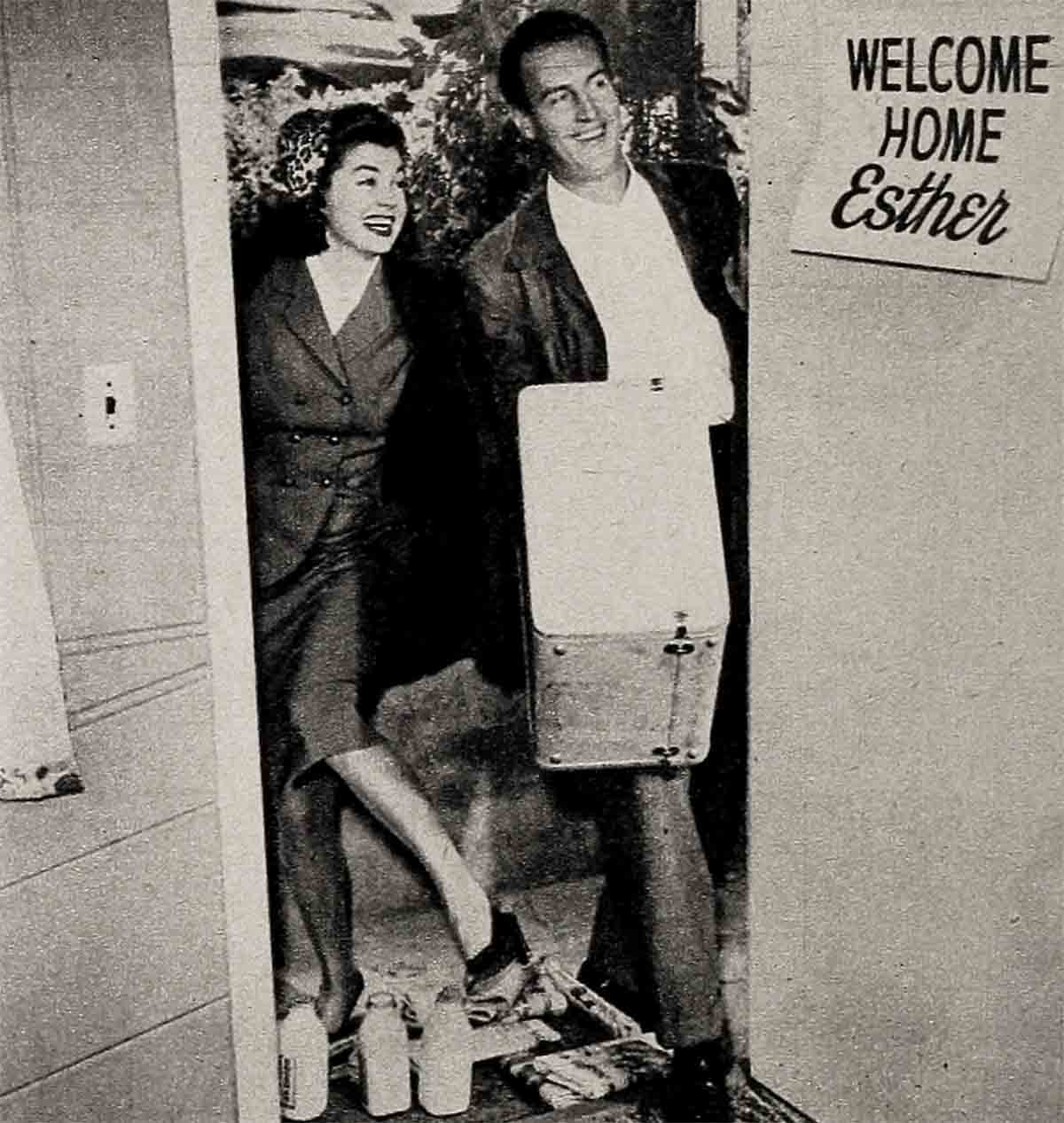

Esther arrived by train. She did not backstroke down the inland waterway, through the Panama Canal, and up the coast of Mexico in a sequin-spangled bathing suit, as any male animal who has seen her in action might reasonably expect. She came in on the streamliner, as demurely as any bombshell, and leaped into the arms of her six-foot-five husband, name of Ben Gage. Keep that in mind, gentlemen. Six-foot-five. And Mr. Gage was so glad to see her that he had not only had signs stuck up around Union Station, but had a “Welcome Home”’ device floating in the home swimming pool.

It was a cold, sunless day, but to show how good he felt about getting Esther back, Mr. Gage took a header off the ten-foot board, and splashed water all over Southern California and parts of Canada. It is not true that the Williams-Gage pool contains essence of pure adrenalin.

If you are not a movie star, and have never made a personal appearance tour, perhaps you do not know that this great American folk custom often is, from the point of view of the star, like being a captive queen in a Roman orgy. You get poked, tugged, examined and cross-examined, exhibited, made to dance and perform, and in the end they throw you into an arena and let wild animals maul you. Strong gents like James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart have been known to grow pale and weak at the knees in the presence of fans determined to pull them apart, tear out their hair and make away with their garments for souvenirs.

Esther Williams, the pastel-tinted bathing beauty, faced that sort of thing for a month and emerged as fresh as a nymph on a calendar. Had a whale of a good time. Thrived on it.

The Williams tour, a friendly gesture by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, designed for the purpose of having Esther meet the people and say a good word for that nice picture, This Time For Keeps, began in Washington, D. C., in a cinema-vaudeville house where it was appropriate enough for Esther to shuck down to a glittering bathing suit.

After that, in more conservative cities, she appeared on stage in a sweater and skirt. Since she is a professional swimmer, she and her manager, an energetic lady named Melvina Pumphrey, were confronted with a slight technical problem. How you gonna lug a swimming pool all over the Eastern seaboard?

This was beyond the resources, even, of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Miss Williams decided to walk on stage and answer questions. She got ’em fast. The first question asked everywhere was: “How about a date tonight?” Having disposed of that the way any nice girl should, Esther then met these queries head-on:

“What does Frank Sinatra look like?” Esther said he looked like a pipe-cleaner with ears.

“Is it true about Jane Russell?” Esther replied that they did not move in the same sweater circle.

“What about Communism in Hollywood?” Esther wouldn’t know about subversive activities. She said all her activities were submersive.

She took a male consensus of long skirts. The consensus: They’re awful. But one Johns Hopkins student said he didn’t mind, he had a long memory.

“What movie star do you like to kiss the best?” Esther got that question everywhere. She replied by getting the questioner on stage, and putting him through a little scene in which the poor, anxious fellow expected to get kissed and didn’t. She also sang a little song entitled “Can’t I Do Something But Swim?”

She did four shows a day, two or three radio programs, and three or four press conferences. She walked in parades with high school drum and bugle corps. (“Felt silly, but it’s fun.”)

She visited hospitals, doing thirty wards, when necessary, to see everybody. She had pictures taken with everybody who came on stage. She called for one boy to come up in a Boston appearance, and got four Harvard men. They stayed through four shows and turned up later in her hotel room. Miss Pumphrey gently pushed them out. They followed her by telephone all over New England and said they would be in Hollywood soon. The Yale men, Miss Williams found, were co-operative but twice as conservative. Late at night, the Misses Williams and Pumphrey did their own laundry in their room.

In Boston, which was new and fascinating to them, they wanted to do some sightseeing. A theater manager shoved them into a car and sent them forward to their next split-second engagement. “I’ll send you a book about Boston,” he promised.

In Providence, they had a half-hour to spare, tried to shop for antiques. Real antique lovers don’t walk into stores and pay the first price. They haggle. Haggling is necessary and expected. When Esther appeared with four motorcycle cops, a fur coat and an orchid, the jig was up. Prices in pewter and highboys inflated like bubble gum. Free advice: Don’t wear orchids while haggling.

In New York, Esther played four theaters, met the press, met the fans, was photographed, admired, and tugged at. In her Warwick hotel room, the telephone rang. “Long distance,” said the operator. “California calling.” It was Ben Gage.

Mr. Gage said he was fractured, said he was lonely, said he was sad, forlorn and six miles lower than a deep blue funk. Said the dog was lonely, too.

Esther brushed tears from her eyes as she hung up the phone. There was a rap on the door. She opened it abstractedly. Ben Gage caught her in his big arms.

“He fooled me all the time,” says Esther. “You know, I’m awfully sorry for all the girls who didn’t get to marry Ben Gage.”

Ben, who’s a big time radio announcer and singer, currently on the Joan Davis show, thinks nothing of flying 3,000 miles between rehearsals and bribing telephone operators in order to surprise his wife. If all husbands were like Ben Gage, airplane stock would zoom.

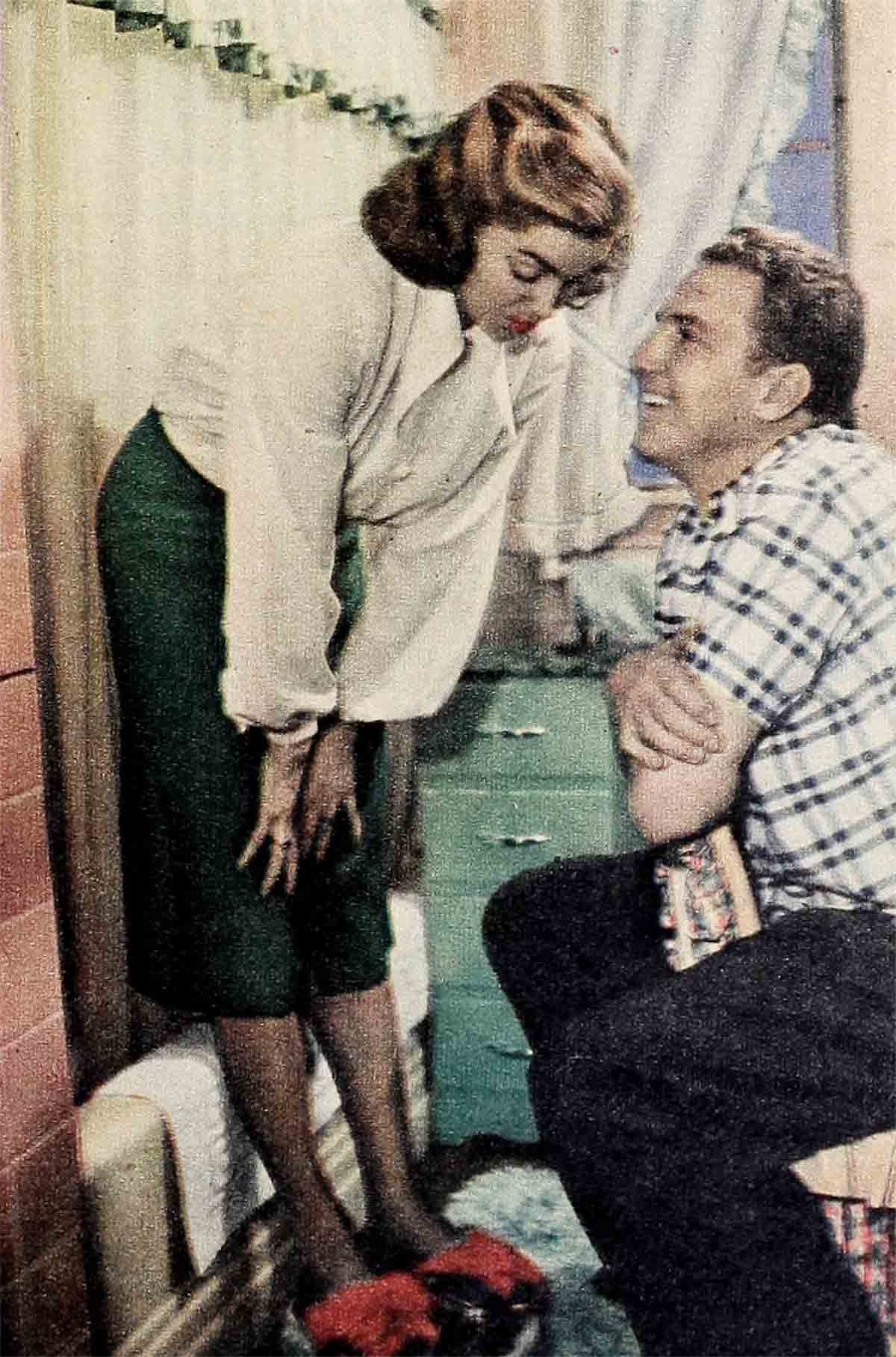

In New Haven, Esther was dressing for dinner after the afternoon show. The phone rang. Miss Pumphrey answered it. There’s a man from the airport who says he’s Miss Williams’ husband,” the operator said. “Of course we know he’s not, but he is a very persistent man.”

Miss Pumphrey, who admires Mr. Gage, pretended to be talking to a fan. She promised to talk to him for five minutes in the lobby. Then she steered Esther down and into Ben Gage’s arms again.

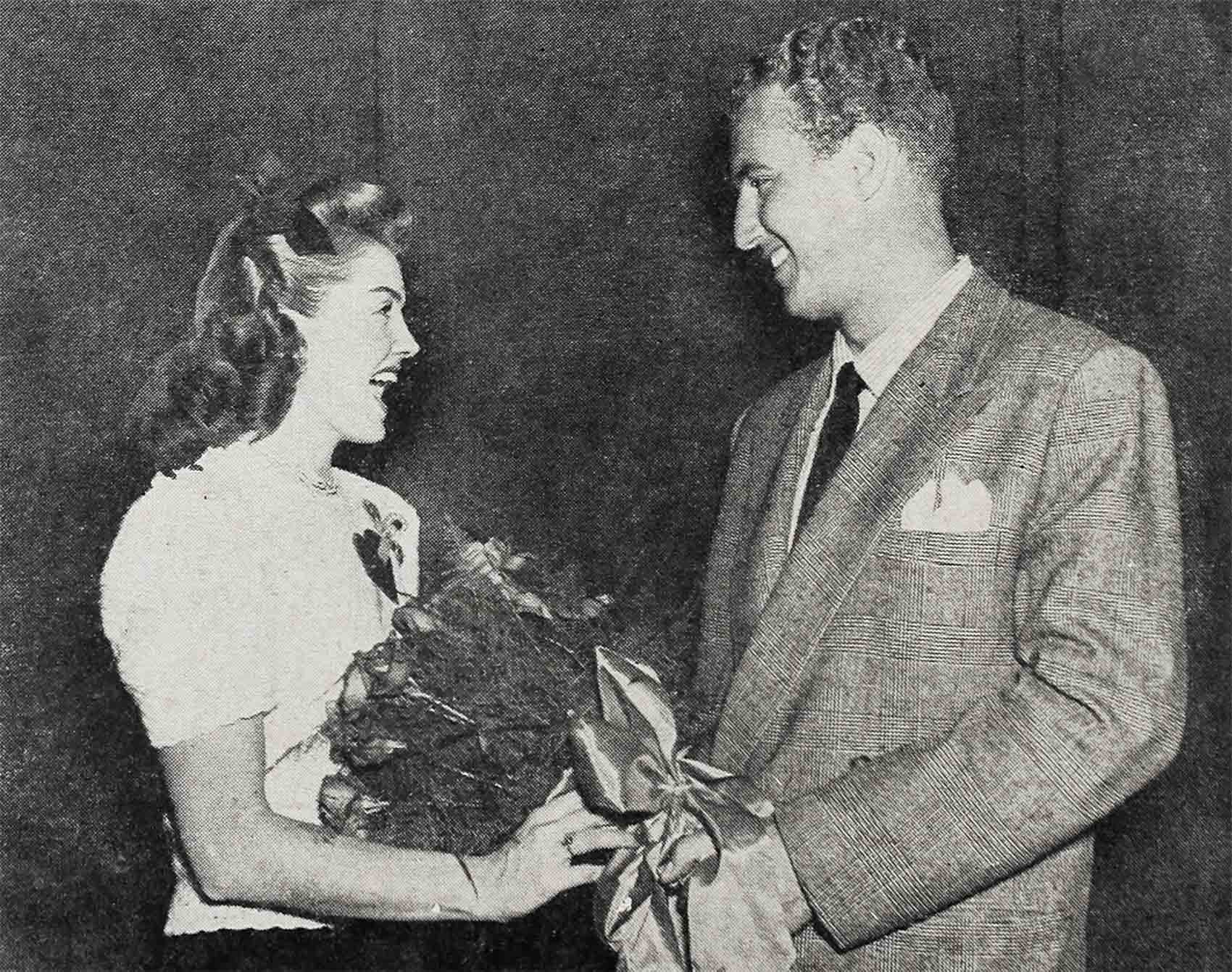

In another city—they can’t remember accurately all the cities they captured—Ben sneaked into the audience, indulged in his favorite trick of bribery, and appeared on stage at the end of the act with an enormous bouquet of flowers.

Esther and Miss Pumphrey got a cop’s-eye view of New England. They went through the countryside in automobiles following state highway patrolmen. Esther thought the New England scenery would be wonderful if it would only hold still.

Her way with people was casual.

“My, what are all you folks doing here? Whom did you come to see?” she asked a jam-packed mob outside the theater in The crowd grinned, moved aside, made way for her. A girl reached for her hair. The cop moved. Esther moved quicker. “If she wants to feel my hair, let her,” she told the policeman. “It’s ‘just hair.”

On one occasion, a squadron of policemen pushed so hard through a crowd that they left Esther completely behind. She remained where she was, safely protected by a little ring of fans—while the cops found it impossible to get back to her. When she decided to go, she grinned and walked through the crowd, which opened the passage without even pushing.

Esther even disarmed the critics, and in Boston, of all places. Boston, as you know, has high standards. Esther addressed the press at an enormous hotel banquet.

She answered questions, was witty, good-humored and, an understatement if there ever was one, a luscious package to look at.

“You surprised?” she asked. “You surprised I could even put several words together? Yes, I know. I make swimming pictures. It seems lots of people like them.

“There’s an enormous studio out in Culver City called Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and way out on the back lot, you will find stage 33, and a swimming pool, and I’ll be there. And orders from the big offices will go down to say the words such-and-such a way, and play the scene such-and-such a way, all these important people deciding on it, and finally the director says, ‘Esther, do it this way.’ And I do it that way. Under water, mostly.”

Esther grinned at the audience.

“When you consider all that, and now that we know. each other, I defy you to be too critical of me. Why don’t you just say, ‘My, why don’t they give this lovely child better pictures?’ ”

That sort of thing brought down the house in a roar of laughter. Miss Williams is now very popular in Boston.

Esther’s homecoming, as aforesaid, was something in the nature of the arrival of a conquering army. All this was engineered by Ben Gage. Mr. Gage planned to surprise her at Union Station with examples of the sign painter’s art, and he did. Being the kind of man he is, he went one step further, and it might as well be told on him. He couldn’t wait for the train to pull in. He boarded the streamliner fifty miles out of Los Angeles, and tackled the conductor for permission to enter Miss Esther Williams’ stateroom.

Conductors plying between Hollywood and the East are sophisticated executives who are accustomed to dealing brusquely with ardent young men who want to get into movie queens’ staterooms. He was considering throwing Ben off, when Mr. Gage escaped in the barber shop. (Those fine trains have barber shops.)

“You’re Ben Gage,” the barber said instantly.

Ben isn’t a man who flabbergasts easily, but this staggered him. “How’d you know?”

“I did Miss Williams’ hair last night. She talked about you all the time. She described you exactly. Which isn’t hard to do, sir, since you’re six-foot-five. I’ll show you where she is.”

And he did, and that’s when Esther Williams leaped into the arms of her husband, and that’s how she arrived home with New England, Baltimore, Washington and New York in her pocket.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948