He’s George Nader!

When George Nader was still a youngster living in the heart of Los Angeles within a bus ride of a half-dozen major movie studios, he came to a very important conclusion.

“All actors are jerks,” said the young Mr. Nader.

And this was not the last time these dogmatic words were heard coming from George’s direction. He was heard repeating them in high school; in his first year at college he pronounced them often and emphatically. For if old George knew anything, he told himself, he knew one thing—all actors were dopes.

But that was years ago. . . . When asked recently, while planting a tender kiss on lovely Maureen O’Hara’s lips on the U-I set of “Lady Godiva of Coventry,” what his present views were on actors, George grinned broadly and reneged. “Work like this is a pleasure,” he said, rather happily, too, considering he was currently employed as an actor.

This was just one of many occasions in which Mr. Nader had to eat those famous last words. And from the looks of things, George is going to have to do a lot more word-eating, because the boy seems destined for a long and successful career as an actor.

Having now appeared in seven pictures. getting his big break in “Six Bridges to Cross,” his talents are thoroughly appreciated by moviegoers and widely recognized by his bosses at Universal-International, who candidly admit, “George is headed right for the top.” They’ve backed their judgment by signing him to a long-term starring contract. It’s obvious that the public agrees with this opinion, for mounting piles of mail on George’s dressing-room floor evidence a fan following to rival Tony Curtis, Rock Hudson and Jeff Chandler. And the readers of Photoplay have acclaimed him “one of the ten most promising performers of 1955,” while the Foreign Press Association of Hollywood has named him “one of the Stars of Tomorrow.”

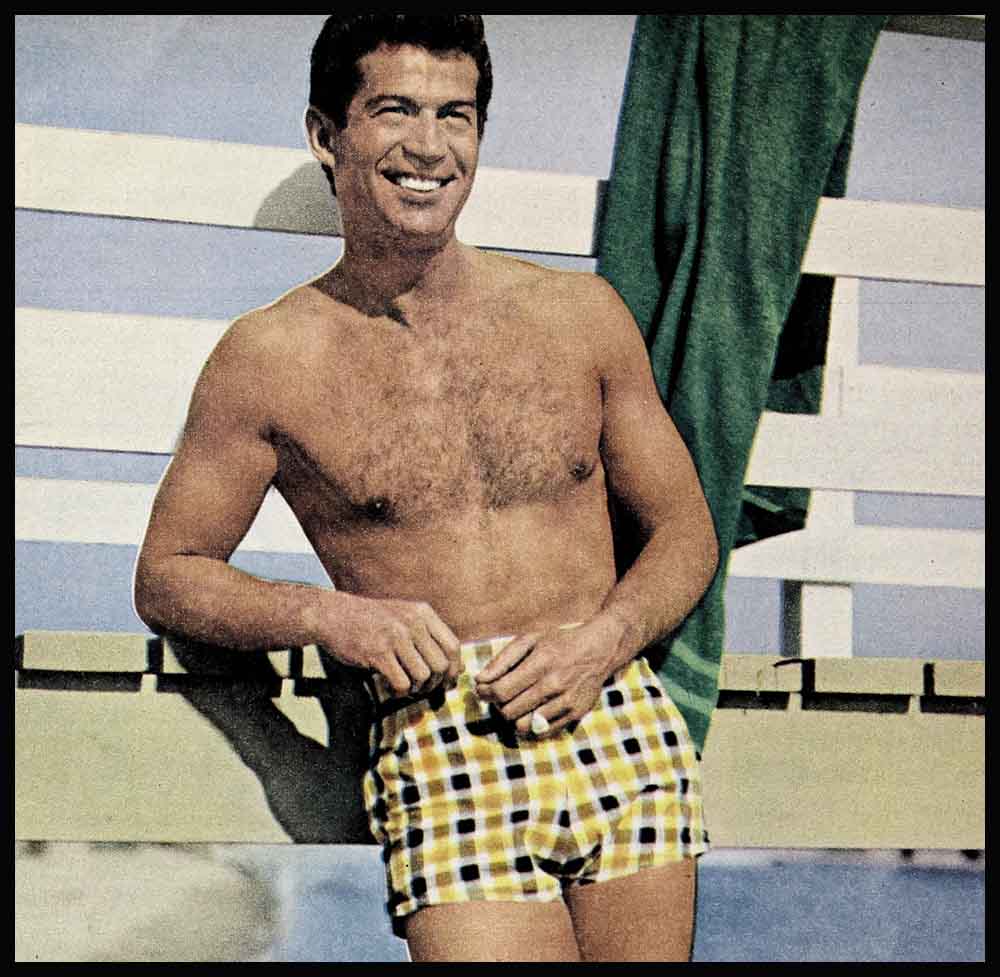

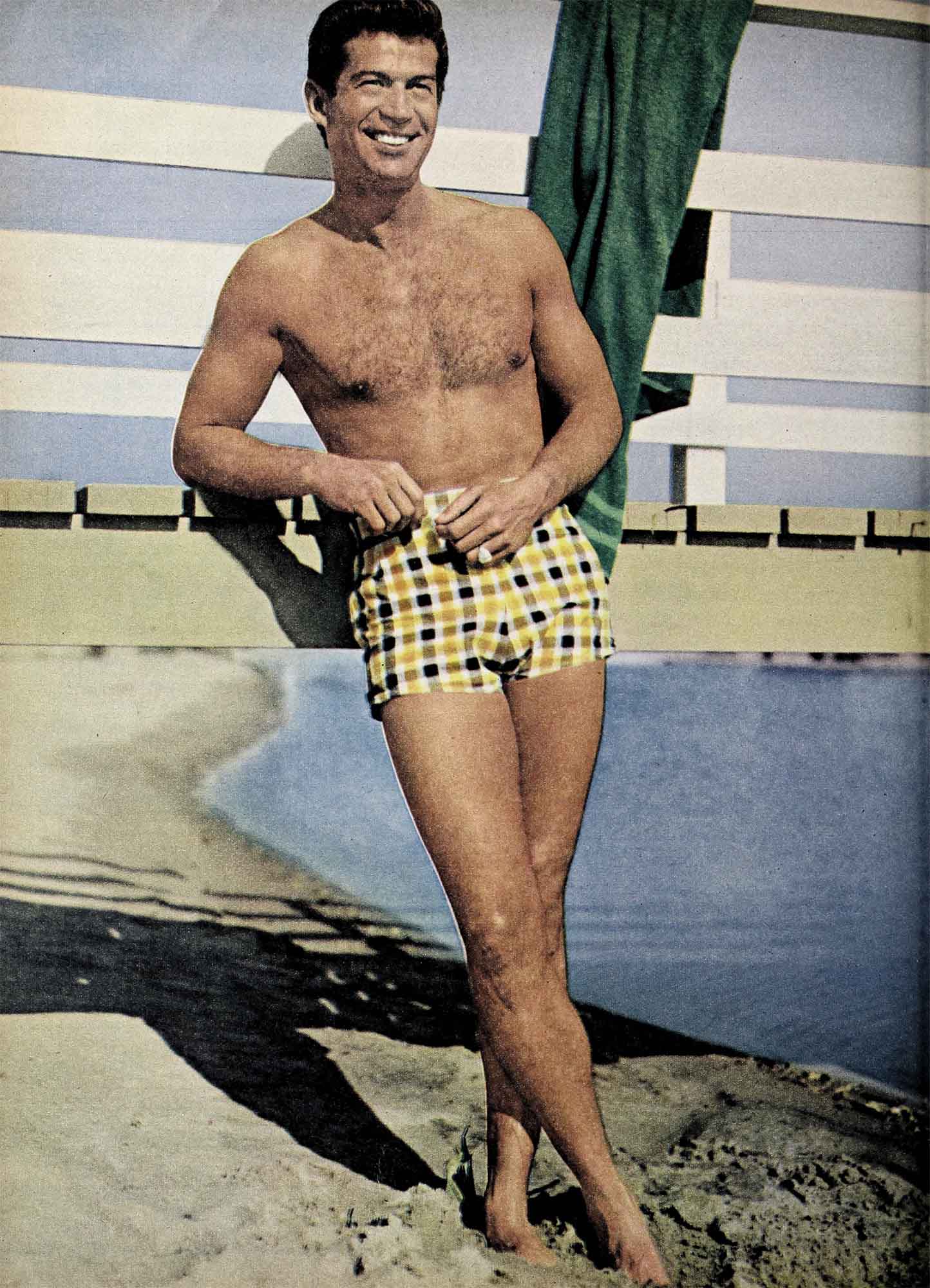

Despite experience in a variety of roles, from tragedy and classic drama to light comedy and romance, George Nader’s future seems surely to be occupied with movies of adventure and romance. He’s the romantic type. Tali, well over six feet, he tilts the scales at 185 pounds. His eyes are gray-blue; his hair wavy brown. His teeth are white and perfect; his grin, warm and frequent. Broad shoulders and a well-muscled body will insure him high rating in the beefcake department. Like Gregory Peck and Clark Gable, George is not a pretty man. Rather, his features are rugged and lively and interesting—the kind of looks that attract and hold a faithful fan following. In addition, and certainly a point not to be underestimated, he has considerable experience in depicting tender passion.

On TV and in the movies, he’s romanced, among others, Loretta Young, Ursula Thiess, Anne Baxter, Julie Adams and now Maureen O’Hara. And when his interlude with Lady Godiva is completed, he will immediately take up pursuit of Jeanne Crain in a connubial love comedy provocatively titled “The Second Greatest Sex.”

He will be kept so busy, according to present plans, that he’ll have little time for the beach (“I enjoy swimming and going to the beach more than anything”) but probably will be spending more time at the piano (“Playing the the piano is the best way to relax I know”). He has a Kimball grand piano in his San Fernando Valley cottage and when he’s particularly tired or tense he sits down and plays some Ravel, Rachmaninoff and Cole Porter.

“I’ve had the piano ever since I first took lessons,” George says. “It’s like a real old friend.” And of his ability to play, “I’m happier about that than any other thing I’ve learned.”

But it wasn’t always so. Years ago, a small boy stood beside that piano, clenching his fists. “I hate it!” he shouted defiantly through gritted teeth.

“You must practice,” Mrs. Alice Nader told her seven-year-old son firmly. “To learn, you must practice.”

“No!” he stormed.

“Yes,” she said calmly.

One hour of daily practice was the rule. For a good musical groundwork, this was not excessive. But to George it was time that could be better spent swimming or reading or just looking at trees and dogs.

However he bent to the adult will. Grudgingly, with black-browed reluctance, he ran his scales and finger exercises. While a succession of music teachers badgered him with technical commands.

“Make the run like a little string of pearls, George,” they told him. “Let each note fail on the ears like raindrops in a pool.”

And with his back turned to the teacher, the small boy made a horrible face and kept plodding up and down on the keyboard until his arms and fingers ached.

George’s father, George Nader, Senior, is a broker and salesman of real-estate and oil property. “There are no other actors m our family,” George says today, “but Father could have been a good one. He’s very personable. He’s a real live-wire.”

The Nader home—Spanish type with a red tile roof—was located right in the heart of Los Angeles, but George had no interest in such things.

School occupied his time. That is, school and music lessons and Christmas and vacations and going to the beach. Happiest are the memories of the family beach home at Playa Del Rey, which is on the ocean just South of Santa Monica. “That was where I learned to swim and battle the surf and love the sun.”

A neighboring town, Venice, was a place of wondrous fascination, too. Patterned after the Italian city, it was a labyrinth of man-built canals (unhappily long since filled in) populated by all types of marine craft from punts and canoes to sleek power cruisers. And filled with an excitement of strange sights and wonderful pungent smells.

“The locks where they controlled the water level was one of my favorite haunts,” says George. “I used to hang around there by the hour.”

The young man was a romantic. He had a taste for adventure and a yen for derring-do and faraway places. And the librarian at the Venice Public Library knew him well.

“What’ll it be today, Georgie?” she asked him, “mysteries or travel? Or some of both perhaps?”

George grinned. Alternately he squatted and tiptoed in front of the book stacks until he found what he wanted and trudged home with his weekly load of five books, the maximum allowed on one library card.

Sherlock Holmes, Moby Dick and Huckleberry Finn companioned his daydreams. The works of London, Stevenson, Melville, Twain and dozens of others tugged at his imagination. Tales of the lost tribes of the Incas and Mayas held him wide-eyed. And one of his special favorites was titled “Stowaways in Paradise,” which told of two kids who stowed away on a ship and took a voyage to Hawaii and the islands of the South Seas.

Years later when George sailed there as a Naval officer during the war, he was prepared for disappointment. But his dreams had not failed him. “The islands were exactly as I had imagined them,” he says.

George was an only child, but he was not lonely. “My mother’s family was a large one; she was one of seven children,” he says. “So I had lots of cousins to play with. My grandparents had a big old-fashioned home on Menlo Street and that was where the family usually gathered.”

Christmas was a magic time. “Of course we all went to Grandfather Scott’s. He was head of the Cudahy Packing Company, and the table always groaned under the huge roasts of beef and ham and turkey. Grandma had spent days in her kitchen baking all sorts of pastries, pies, cookies and fruit cakes. She did it all herself. She wouldn’t let anyone help her. She said it was her job to do the cooking for her family. Of course all of us, especially the kids, stuffed ourselves until we ached.”

But life was not all fun and happy times. George was thin as a fence rail, and he was plagued by a succession of childhood ailments. Chicken pox, mumps, measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, all of them. Hypodermic needles of vaccine to ward off diphtheria were a special terror and left their mark on his memory as well as his body. To this day he abhors them.

“George, you musn’t tell about being so sick,” his mother said recently. “People will get the idea that we didn’t take care of you properly.”

“Oh, come now, Mother,” he said. “Lots of kids get such illnesses in spite of anything their parents can do.”

As a result of these afflictions, George spent a good deal of time in bed and away from school. But he didn’t fall behind in his studies. His mother had once had a teaching certificate, so she tutored him at home. As an extra inducement she bought him a 12-volume set of “The Book of Knowledge.” “They were wonderful books,” he remembers. “They had all sorts of school tests in them and they were fun besides. The pictures were really something.”

Eventually, however, Alice and George Nader decided that the boy needed a complete change. They sent him to a boys’ camp and school in the San Gabriel Mountains back in Azusa, California. There were about a hundred boys there, some of them sickly, many of them suffering with asthma. George was ten years old.

“We practically lived out-of-doors,” he says. “We got as much fresh air and sunshine as possible. We slept on screened porches. We drank a big glass of milk every mid-morning and mid-afternoon. Except on the very coldest days, we never wore anything more than shoes and a pair of shorts.”

There was an earthquake that year. Everyone ran out of the dormitories to watch.

“Hey, look a the ground! It’s shakin’!”

“Are you scared?”

“Nah! What’s to be scared of?”

“Look out for the boulders comin’ down the hill!”

After a year at the camp, George came home, his health fully recovered. He was brown as a Sioux, and a dozen pounds heavier. Bursting with energy, his blood fired with newly acquired red corpuscles, he promptly fell in love.

“Her name was Geraldine,” he says in blissful reminiscence, “and she had long red hair. I was quite mad about her.”

Their romance blossomed on the school grounds. It bloomed while they trysted on the parallel bars where Geraldine excelled at “skin the cat.” That year there was a snowfall in Pasadena and the lovers spent happy hours building a snow man. But nothing ever came of all this.

“I guess it wasn’t meant to be,” George says sadly.

All in all, the world was a good place for George that year. Except for one very dark cloud. The music lessons, postponed during the year at camp, were begun again. And along with them came a new form of “torture” known as the recital.

One well-remembered occasion took place at the music teacher’s home. There was an audience of mothers and dads, alternately beaming and nervously ruffling their feet. The program consisted of a crashing rendition of the William Tell overture, performed by a full orchestra complete with wood winds and lots of brass. And two pianos yet, one of them George. “It was awful!” he recalls.

Then another time George was called upon to play a solo. “I played ‘Country Gardens’ by Percy Grainger, and I guess I got through it, but I don’t know how. My face was hot and flushed, my arms were paralyzed, my mind was a complete blank.

I was in a blind panic.”

Despite these agonies. George did manage to gain considerable musical competence and facility. By the time he reached high school he was playing exceedingly well. And when he decided that he wanted to study popular music, his parents readily agreed.

“I studied harmony for about six months,” he says. “I had a good groundwork and the fingering was not too difficult. After that it began to be fun.”

However there had been a turning point before this. While in grammar school, his class had attended a performance of The Yale Puppeteers at Olvera Street, a Mexican show place in downtown Los Angeles. Later, as a class project, they built their own puppet show. George was entranced. Within him was born a deep desire to learn more about stagecraft and the theatrical world.

“I got an old piano box and built my own puppet stage in the back yard. Then I made the puppets out of plywood. When I was ready I gave a performance for all the kids in the neighborhood. It was exciting and fascinating. I had really been bitten by the theatre bug.”

When he was in Junior High School, George bought his first automobile, a 1932 Ford coupe. He had earned the money himself, as a summer clerk in a grocery store, and as a messenger for a photostating firm. That year his pride got another boost when his father gave him a key to the family front door.

“You mean I am now to come and go as I please?” he asked.

“Yes, George,” his father said. “You’re old enough now to know what’s right and best. From now on it’s up to you. Your mother and I are not going to worry about you any more.”

The following year, in Glendale High School, George tell in love again. Having fully emerged from under the titian spell of Geraldine, the gay inamorato now went into a full spin over Arlene, a corn-silk blond. “She was fabulous!” he says. “The most exotic thing I had ever seen.”

What seems to have intrigued him most, and held him in a strange fascination, was the fact that Arlene’s blondness was not only self-induced but self-admitted.

“What you do is take a box of Lux and a bottle of peroxide and mix them up together,” Arlene explained forthrightly. “Then you use that to wash your hair.”

George gazed at the object of his affections with open-mouthed adoration. Following the tradition of lovesick swains, his tongue failed him completely. And in the face of this astounding pronouncement the only thing he could think of to say was, “Gosh!”

However the romance of Arlene and George was of short duration. In fact it never really got started.

“I just worshiped her from afar,” he now says. “Actually she was a little too expensive for me. Oh, sure, I had a Ford and a few bucks to spend on dates. But Arlene was a kind of girl who was destined for bigger automobiles and four-letter men.”

George’s spirit was far from crushed. His real love was the theatre, the mechanical theatre of footlights and flies and painted sets. The Glendale High School auditorium was completely equipped with everything a legitimate theatre needed. This was what George had long looked forward to. He immediately enrolled for a course in stagecraft. “It was the only thing I was really interested in.”

George makes it very clear that he didn’t study dramatics. “I wasn’t the least bit interested. And besides I didn’t think very highly of actors as a group.” He became a member of the regular stage crew, and studied stage design and practical stage management. He started as a helper, and learned to build and paint flats. He learned all about lighting, too. For example, he learned that a dark blue bulb over a stage door can be twice as hot as a white one. When he grabbed one it sizzled and smoked in his bare fingers.

“I got second degree burns,” he says. “The kind where the top flesh peels off. I learned that one the hard way.”

That year there was a school production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta, “The Gondoliers.” For the second act a full back set was hauled into the flies high above the stage. Without counterweights, this was so large it required three stagehands to handle it. But during the first performance George and another equally enthusiastic but unthinking helper tackled it alone. They were outweighed. They untied the set and it descended with a crash, while they soared upward.

“We dangled there like a dowager’s lavalier,” says George. “It was pretty embarrassing.”

Despite such mishaps, and the added hazard of a stage-crew member named Sandra who “managed to look outstanding even in coveralls,” George made rapid progress. In his senior year he was advanced to full stage manager. That year the auditorium was used for a Police Benefit Show and George had his first chance to work with a top-flight movie star. Her name was Judy Garland.

At Occidental College George went on with his stage work. “Their theatre-auditorium was called Thorne Hall, and it had a wonderful stage. Everything was almost brand-new. all they lacked was someone to manage it. When they found out I had a lot of experience they seemed very glad about it. They immediately made me stage manager. Naturally I was delighted.”

The following year George got his first taste of drama from the actor’s point of view. A brother Phi Gamma Delta had written a play, and was trying to cast and produce it. He approached a group of fraternity pledges, George among them.

“We seem to be short of actors,” he told them. “You are about to volunteer.”

“Thanks, but no thanks,” the lowly pledges chorused. “We would rather die.”

“We shall see,” said the playwright. “I direct your attention to this large wooden paddle I hold in my hand. Now bend down, men. Assume the angle.”

This persuasive tactic was irresistible. The pledges became actors.

“It was one of those oblique dramas,” George says. “The dialogue consisted of the thoughts of the different characters, and so it was tape-recorded. On stage all we had to do was suit the action to the words. But I was scared to death just the same.”

Nevertheless George was interested. And this was a beginning. He sought out his next role in a comedy “Out of the Frying Pan.” When, on-stage, he spoke some funny lines and heard the audience laugh, it was a moment of decision. He told himself, “This acting business is pretty easy stuff.” After that he switched completely from the mechanics of management to the nuances of portraying drama. He appeared in a long list of plays including “Guest in the House,” “Murder Has Been Arranged” and “Kind Lady.” In his final college year, before he was graduated with a B.A. degree, he was elected president of the Drama Society.

“Next,” he says, “there was the war.”

After three months of intensive study and training, George became a Naval officer, or as he terms it, “a ninety-day wonder.” He served as a Communications officer in Hawaii and on Johnston Island in the South Pacific. Then, after his discharge in 1946, he spent three more years learning his theatrical trade at the Pasadena Playhouse. After he graduated with a degree of Bachelor of Theatre Arts he felt that he was ready for Hollywood.

But Hollywood did not seem to be ready for George.

Is there a greater frustration than that of a man who seeks a job and cannot find it? Surely not, unless it be the pangs of an unrequited love. George’s hopes skyrocketed when an agent approached him with happy talk of a movie career. Then they plummeted when the agent failed to produce anything even faintly resembling a job offer. But finally a break came.

Mrs. Loretta Crain—Jeanne’s mother—saw him acting at the Pasadena Playhouse in Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie.” Convinced that he was a comer, she got Jeanne interested, too. Together they arranged interviews for George at 20th Century-Fox. As a result he was offered a screen test.

George was jubilant and profoundly grateful to Jeanne and Mrs. Crain. “They really went all out for me,” he says. For his test he did a scene from “The Glass Menagerie” with Colleen Townsend, and he felt that he had done a good job. But he was doomed to bitter disappointment. At the same time the studio had tested another young actor. He was signed to the contract; George was not. It was a blow to him.

“When I got the news I felt miserable. I couldn’t have felt worse.”

But his spirit was not broken. When they offered him a small part in “Take Care of My Little Girl,” he accepted it. He worked exactly two days at a minimum salary of $125 a day. Then after a few more minor parts he met a TV casting director named Ralph Acton and his career really began to roll. He made a top-budgeted picture in India and another in Germany, “Carnival Story.” And television viewers saw him many, many times.

Today Barbara Stanwyck, with whom George played in a radio drama, is one of his closest friends. He is grateful for her encouragement and her advice. Loretta Young was helpful, too. Of her, George says, “She’s the best teacher I ever had.”

When George was offered his contract at Universal-International he still had a commitment for two “Letter to Loretta” TV shows. This might have jammed things up, but Loretta proved to be a good friend and released him. “It’s a fine opportunity. Go and make the best of it,” she told him. “And God bless you.”

Now George’s future is assured. Despite Geraldine and Arlene and Sandra, he is still unmarried and apparently heart-whole and fancy-free. But a friend says, “I know he has a great fondness for a girl who lives in Pasadena.”

At present, however, aside from relaxing at the beach and playing the piano, George is concentrating on his career—and admitting again that there’s more to acting than met his young undiscerning eye.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1955