The Truth Behind The Rumors That James Dean Committed Suicide!

It is difficult if not impossible for the people who knew and loved Jimmy Dean to believe that he felt his search for personal happiness to be so futile that he might have entertained thoughts of suicide. And yet, anyone who observed him closely could not help but be aware of the black moods that closed down on him so suddenly, shutting him away from everyone. During the filming of “Giant” in Marfa, Texas, dialogue Coach Bob Hinkle said gloomily, “Some day that guy is going to drive his car right off a cliff.”

That was in July, 1955. Less than three months later, on September 30th, Jimmy’s broken body was being lifted out of a twisted heap of metal that had been his German-made Porsche Spyder racing car.

On the day he was killed, he was stopped at Bakersfield and handed a ticket for going sixty-five miles an hour in a forty-five mile zone. “You’d better take it easy, son,” he was warned “or you’ll never make it to Salinas.”

When he stopped for coffee at a place called Blackwell Corners, he met Lance Reventlow, son of Barbara Hutton and, ironically enough, owner of the light plane in which the late Bob Francis was killed, also a year ago. Jimmy boasted of having hit over 100 miles per hour on the trip up. It must be remembered that this was on a public highway. A racing ear is not meant to be driven on the highways. There is no windshield to protect the driver, no steel top. The body is made of lightweight aluminum. Driving at such speeds, under such conditions, might well be called suicidal.

But the people who knew him well are still inclined to brush aside as nonsense any suggestion of suicide. In the little booths in Googi’s, on the Strip, where Jimmy was so often a part of the crowd that gathered for hamburgers and coffee, they point out that Jimmy had often said, “If I live to be a hundred I won’t have time for all the things I want to do.”

At Schwab’s Drug Store right next to Googi’s, where Jimmy got his first taste of what it was like to be famous—by finding that he was the guy the gang stuck with the tab for their ham and eggs in the morning—the talk of suicide is also dismissed. The young actors on the way up and old actors on the way down who line the counter each morning at about eleven o’clock all shake their heads and say, “Don’t be silly. What would a guy like that want to kill himself for? Why, he had everything. He was on top. His agent had him signed up for five million dollars’ worth of movies for the next two years!”

That remark would have brought a wry, twisted smile to Jimmy’s thin, sensitive artist’s face. Because from the first morning when he found himself stuck with the tab right up to the last night of his life, Jimmy Dean viewed his mounting fame with suspicion, distrust and, finally, active dislike.

“My fun days are over,” he said more than once, and by that he didn’t just mean his days of irresponsibility, when he was accountable for his actions to no one but himself. What he really meant was that the days of struggle were over. He had achieved so many goals, and again the achievement had brought not fulfillment but frustration. In his heart, he didn’t believe that he deserved all the adulation he won. Therefore, he thought the people who rushed to tell him how great he was were phonies, seeking to curry favor with a star. His moods deepened as his fame mounted. His reputation for eccentric and even shocking behavior grew in direct proportion to his constantly increasing reputation. He quarreled with close friends. He walked out on dates. He went around, as several people have remarked, “looking like a tramp.” He would go for days without shaving.

Even Jimmy’s sense of humor had a part in shocking his friends. A group of them were not surprised, entering his apartment one night, to find a noose hanging from the ceiling and candlelight casting eerie shadows on the wall. In a similar mood is the set-up he devised for a camera study, in which a kitchen knife in a mirror became a threatening dagger.

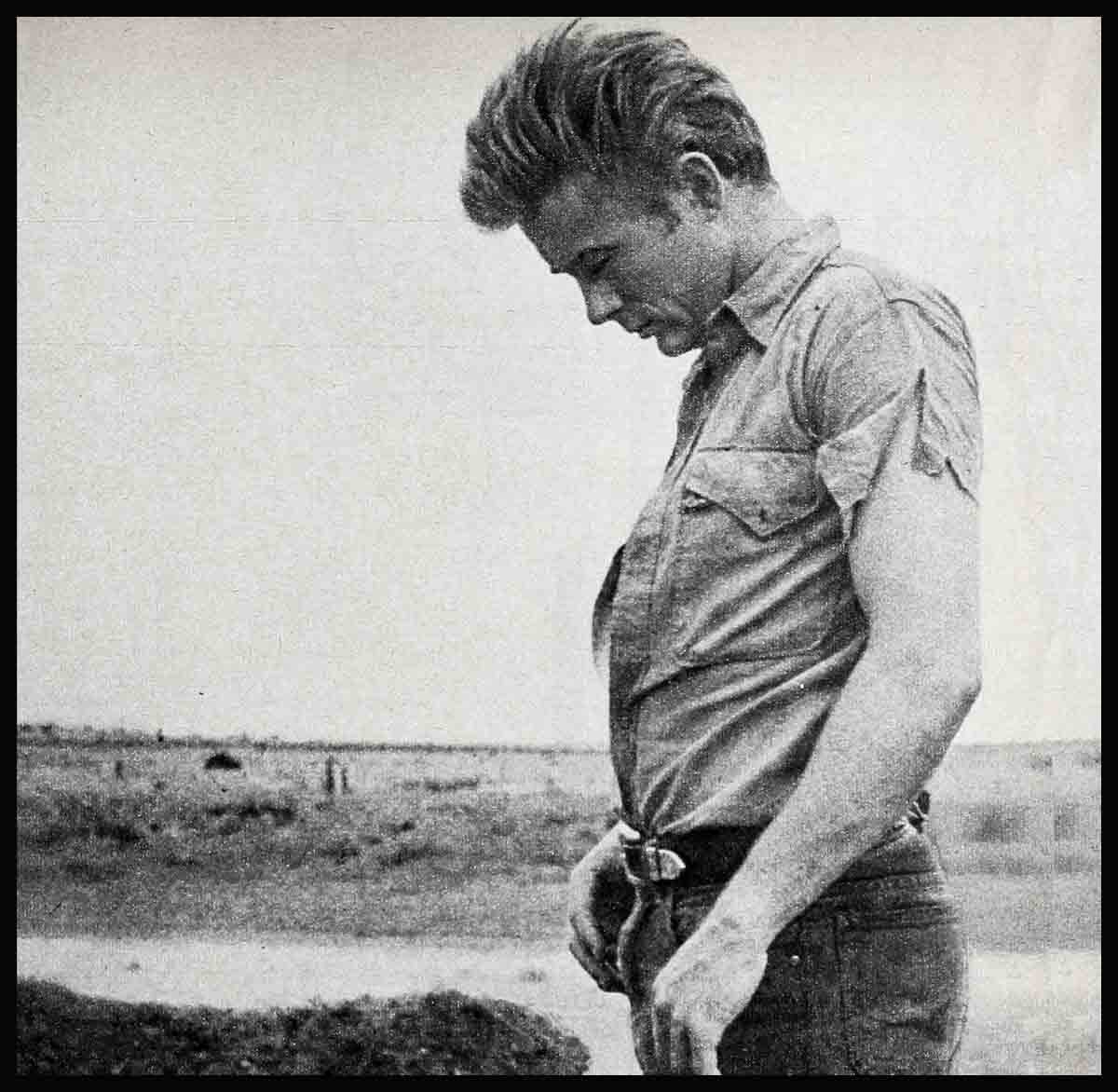

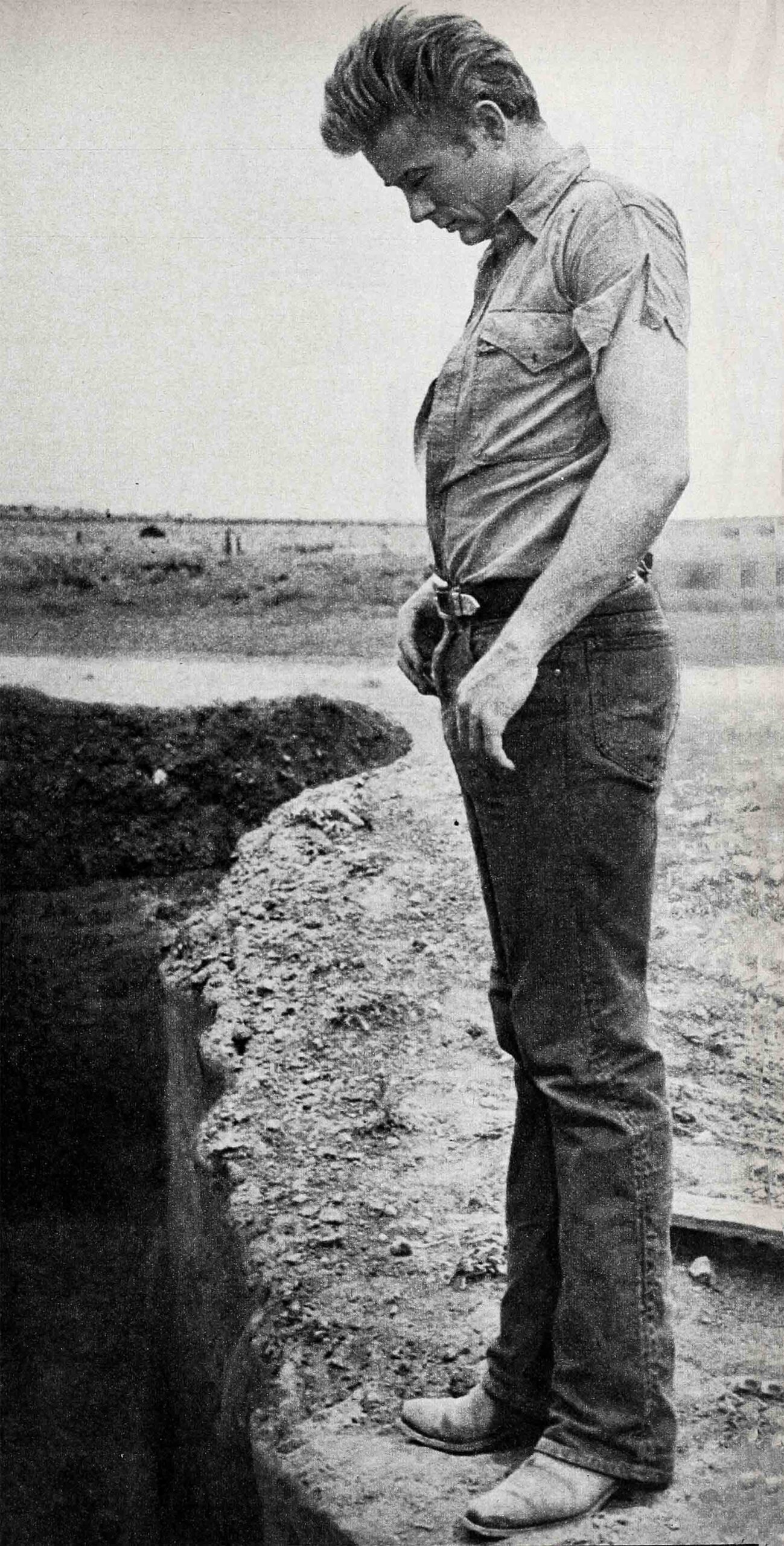

Then, there’s the often-told fact that Maila Nurmi, otherwise known as Vampira, sent him a picture of herself beside an open grave with the message, “Darling, come and join me.” Was that invitation in his mind when, in the picture on the opening spread of this story, he stood transfixed, staring into a yawning ditch?

The more he withdrew from this world, the more he seemed drawn to the other world. Jimmy Dean was always intensely interested in the metaphysical. Even as a young boy in Fairmount High School he wrote a composition that said, “Why are we compelled to live in one world, to wonder about the other world?”

His deep attachment to the mother who died so young was undoubtedly at the root of this preoccupation with death and what, if anything, there was after death. A heartbroken young boy’s fierce refusal to believe that a beloved parent is gone from him forever is easy enough to understand. When this is heightened by a vivid imagination and fed by a self-imposed loneliness it could, as in many ways it did with Jimmy Dean, become an obsession. An obsession that became part of his endless search for some truth which he could recognize as absolute and which, therefore, he could believe in.

By the time Jimmy had reached Hollywood, he was already steeped in books and philosophies having to do with the occult. He had also begun to build his powers of concentration to a degree that was almost superhuman. Anyone observing Jimmy when he learned to spin a rope better than a rodeo rider, or to master some other needed skill, never failed to comment on his ability to cut himself off completely from everything and everyone around him for those periods of concentration. He would sometimes force himself to stay awake all night, deliberately choosing some trivial task to perform, so that his concentrative powers, not fascination with the work at hand, would be the thing that kept him fully alert around the clock.

What did this have to do with the possibility that Jimmy might have been contemplating suicide at the time of his death? The Hindu philosophy believes that, if we develop our powers of concentration to the fullest, we can penetrate the veil between this world and the next.

Is that what Jimmy hoped to do? And failing that, was he still so obsessed by the will to know all, not only about this world but the next, that the thought of dying slowly took over the more abstract thoughts about death? It is no secret that he was constantly disappointed—in friends, in love, in himself. The number of his friends steadily dwindled. His love of speed increased. He had moved from a one-room apartment to an eccentrically built house in San Fernando Valley, which he had rented from his good friend, Nicco Romanos, maitre d’ at Jimmy’s favorite restaurant, the Villa Capri. But here, as in his apartment, the dishes were seldom washed, the beds were seldom made, the floor was never swept. And here, as in the apartment, callers were few, the loneliness he sought and then hated was constant and the light burned far into the night as he read or played the drums or made recordings of his voice.

And then, a few weeks before “Giant” was finished, when the ban against driving his racing car was lifted, a great many things happened at once. Things that might be explained by the word “coincidence,” although they represent an amazing number of such things to have occurred within so short a time.

Jimmy one day called over good friend and insurance agent Lew Bracker and told him he wanted to take out some insurance. Lew wrote up a one-hundred- thousand-dollar policy and Jimmy gave him a check for the premium. The day before Jimmy left for the ride to Salinas that was to be his last, Lew met him on the Warner Brothers lot and asked him to name a beneficiary. Jimmy scratched his chin, rubbed a finger along his lower lip as he did when he was trying to make up his mind about something, finally said, “Make yourself the beneficiary.” Lew explained that he couldn’t do that. Jimmy thought again but could come up with no immediate name, no one that close to him. Besides, he was late. He had to meet his mechanic and see that everything on the Porsche was in shape for tomorrow’s race.

“I’ll think about it,” drove off.

Lew never saw him alive again. Jimmy’s father, to whom the boy never felt close, has sued to be named beneficiary, since he is the next direct relative.

About a week previous to that time, a photographer named Frank Worth who was also a fairly good friend of Jimmy’s dropped by to pick up a book on photography which he had loaned Jimmy. He was invited to sit down and have a drink and hear some of Jimmy’s recordings.

“They gave me the creeps,” Frank remembered of this later. “They were all about death and dying—poems and things he just made up—about what it might be like to die and how it would feel to be in a grave and all that. I didn’t wait for my book. I just got out of there, fast.”

Even after Jimmy’s death, however, Frank found it difficult to believe that, within ten days of that tragic accident, Jimmy might have been thinking of his own grave when he put those things on a tape recorder. The people who went to his home after his death say that the tape recorders were wiped clean. The recorders are all in the possession of he promised, and

Jimmy’s father, and it seems true that they were wiped clean, because a record company has since offered large sums of money for any recording of his voice. Up until now, no such recordings have turned up.

Less than a week before his death, Jimmy parted with something very dear to him—a gold Saint Christopher’s medal given to him by Pier Angeli at the height of their friendship. He handed it to Nicco one day with the comment, “Here, I want you to have this. I won’t be needing it any more.”

Saint Christopher is the patron saint of travelers, and is supposed to keep them from harm on their journeys.

Like everything else about this strange sequence of events, no single thing about it roused any suspicion in anyone’s mind. It was only when they were all put together that they seemed to add up to a picture of a man who might have decided death would be simpler to face than life.

At the end of Mr. Bast’s story in this issue, you will find yet another incident which, looking back on it now, lends still further strength to the rumors that began shortly after Jimmy’s death, are growing still. And there is just one more conversation between Jimmy and another close friend which might shed more light on this puzzling question. This was a young man whom Jimmy had helped indoctrinate into his own desperate search for truth and a way of life that held dignity and meaning. One afternoon, Jimmy came back from a long absence to report that he had been spending the time with author Christopher Isherwood, who, like Jimmy, also believes in the Hindu philosophy of immortality and the search for an absolute.

“I want you to meet Chris,” Jimmy said, “because I’ve given you the idea now, you know what it is we’re trying to do, and I think Chris can help you carry it out.”

This was three weeks before Jimmy’s death. This was about the time he asked Lew Bracker to write out an insurance policy, and around the time he seemed to give up all interest in his friends, in his appearance, in everything but his restlessness to get back to his racing car.

Jim DeWeerd, a chaplain in the Army during World War II, a cultured man, and a man who exerted a strong influence on Jimmy’s life, has said, “All of us are lonely and searching, but because he was so sensitive, Jimmy was lonelier and he searched harder. He wanted to find final answers, and I think that I taught him to believe in personal immortality.”

And, in a sense, Jimmy has won that personal immortality, though not in the way he might have thought to win it. He has been dead for over a year, and yet he is more loved and more revered than ever. Someone said of him, not long ago, “They just won’t let him die—”

What other kind of immortality James Byron Dean might have found is something we shall never know. Nor shall we know whether, when he started out on that bright, sunny day on a trip that would have no return, there was, in his heart, any thought or hope that he might not come back. Even if he had that thought, or that hope, the chances are pretty good that the actual accident was an accident. The question that will never be answered is, “Was it an accident he would have welcomed, had he any premonition of it? And if the end hadn’t come then, on that dusk-shrouded road, would he have willed or wished it to come in another way, in another time?”

Questions that have no answers but questions that refuse to be stilled as a world mourns, and wonders. . . .

THE END

—BY WILLIAM BAST

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956