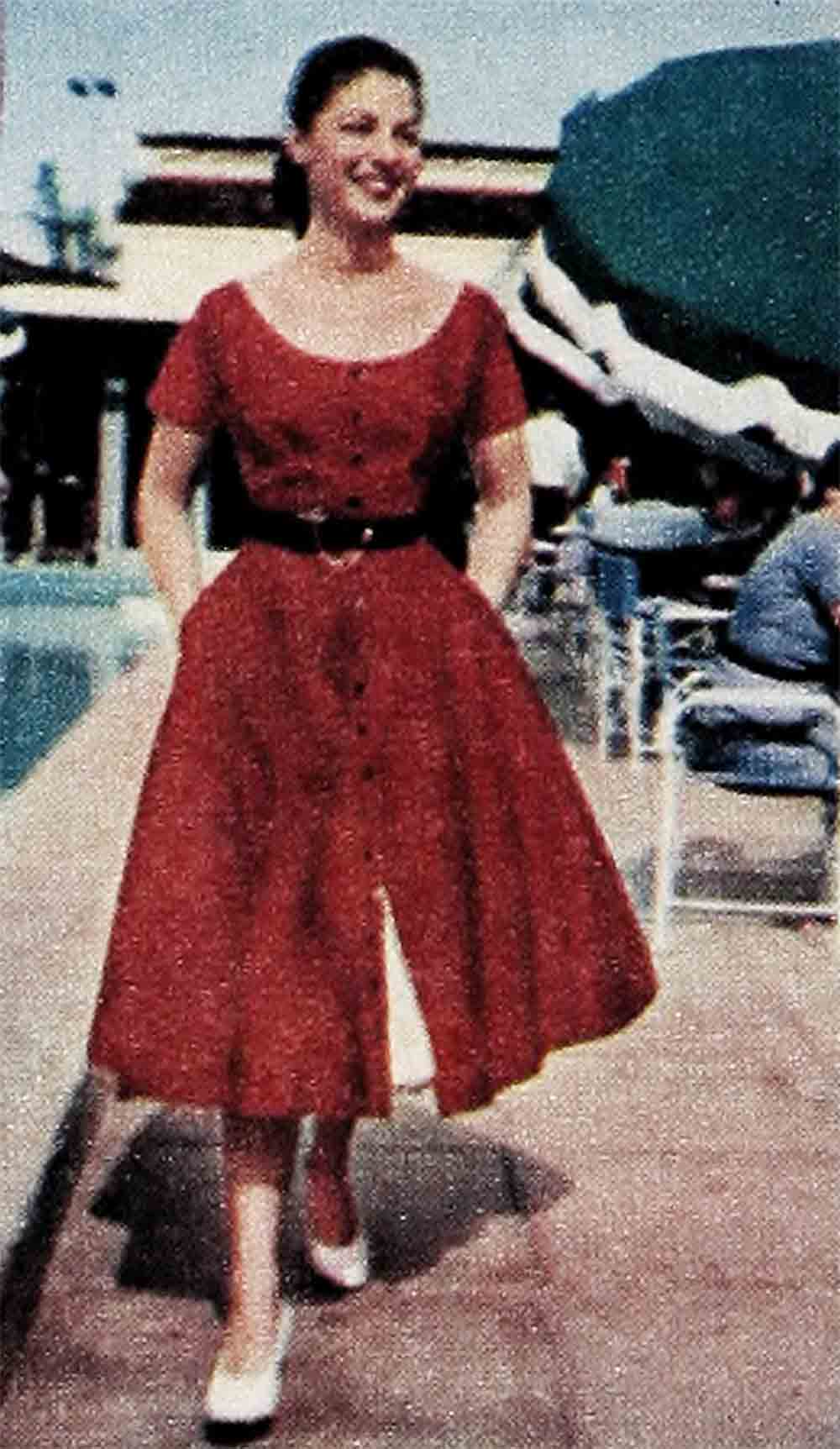

Sleeping Beauty Wakes Up—Pier Angeli

“Only last year,” Pier said, “I really, really grew up. On June nineteenth, nineteen fifty-three, I became twentyone. And when you become twenty-one your growing pains—as it is called in America when you change from a child to a woman—are said to be over.

“It is a very interesting story, the story of my growing pains, because so many people helped me become not a child but a woman, and also because my growing pains, they were different from those of many teen-age girls.

“Some of these growing pains that cause suffering to other girls come from the embarrassment of not having pretty clothes to wear, or embarrassment because, for a time, their skin does not look nice, or they have to wear braces on their teeth, or they are too fat or too thin, or they have not a nice home in which to entertain their 3 friends.

“I did not suffer these kinds of pains. When I lost my first teeth I was, I remember, a little unhappy then. But soon others came and I was happy adios again. And once I was ashamed because my legs were so thin I had to be helped to walk on them. But this, too, passed too soon to leave a scar. I did not suffer from the self-consciousness of adolescence either. I had always the feeling of loving everybody and of everybody loving me.

“My father; Luigi Pierangeli, whom I so dearly loved, was an architect. The best. In Sardinia where I was born (quite a few seconds before my twin sister Maria Luisa, so that I am the elder and like to be the boss!) my father was engaged in public works projects. In Rome, where we moved when I was two, he built beautiful apartment houses all over the beautiful city, and we lived in we of the beautiful apartments my father built.

“My father spoiled me. He even cut up my meat for me! And all the things there are to do in the home and for the children, my mother shouldered. My mother always had the most beautiful taste, so that we were always really beautifully dressed, Maria Luisa and I, and later our baby sister, Patrizia, who is now six. We were dressed always in full skirts, flying and floating around us, and little soft slippers, and our hair was always nice and combed. Until I was sixteen I wore, always, a little crown of flowers in my hair. I was always very fond of dresses, as I am now. I love clothes,” Pier said, a glint in the green eyes under the fall of light bronze hair. “I love them! Every bit of money my mother gives me I spend on clothes, so I have never a nickel in my pocket! So this being always beautifully dressed made me very happy, too.

“My home was my world, and for as long as I was in my home, I did not suffer from a growing pain, not one. I was happy. I wanted to stay always in my home, and always a child. It was this, this wish to stay always a child that became my pain.

“At thirteen, on my thirteenth birthday, I remember thinking how all the things were on my mother’s shoulders. So I had a long talk with myself: ‘Anna Maria Pierangeli, you are changing, I said. ‘At thirteen, you are coming to be a woman. My goodness, stop running around and being a little baby. Playing with dolls any more is no good! You must grow up!’

“But soon I forgot this talk with myself. I wanted to forget it. I wanted not to be a woman. I was happy—and then the war started and I was unhappy. I suffered very much. So much that I was sick in my bed for four months. I had no fever. I had no marks on me of a sickness a doctor could cure. I was—I now understand—in shock. I had so many shocks from seeing friends of mine killed, shot down by Germans in the streets. One, a young mother with her little baby, and she was screaming to me for help.

“I am strong, but sensitive, too. At school I was always trembling. I was fainting all the time, too. When I’d see a German person, I’d faint.

“It was shock. It was also not having the proper foods. We didn’t have any meat or sugar or milk. And we couldn’t do anything about it. There was money, but money couldn’t buy what wasn’t in the city to be bought.

“Soon I just couldn’t move. I lay in my bed more motionless than the dolls I had played with. One day I heard the doctor talking to my mother in the kitchen. ‘I don’t think she is going to live,’ he said.

“I didn’t care. Then my father built me a little room in the apartment. All pink and blue, with all pink and blue flowers on the walls and the floor all made of green glass, lighted underneath. And every day he brought me violets. My father, who couldn’t get me anything else, brought me every day a little bunch of violets, the same as this little bunch,” Pier touched her breast, “I wear today and every day.

“All the professors from my school came to see me, too. And my girl friends from the art school where I was studying to be a sculptor. And so, at last, little by little, I started smiling, and speaking, and moving. Maybe it was a miracle—a little one. I think so. I think it was God.

“At just the time I am beginning to smile again, there is a big party at our house and all these people are there and it was so awful for a girl, fourteen, with legs so thin she had to be held up! This makes me able to feel sympathy with the growing pains of girls who have legs too thin, or too fat, or not a good skin or something that makes them embarrassed with themselves.

“But for the most part my growing pains were not caused, as I have told you, by these problems. What caused me pain as I grew was that in my childhood I did not know, was not permitted to know, did not want to know what is in the world. Until the war came, I saw people all like my mother and father, all kind and tender and taking care of me. I wanted not to see the world and people any different. I fought not to. I had always my hands in front of me, in front of my face. I didn’t want to face reality. What is in the world I didn’t want to know.

“One of the first to help me come out of my childhood was Leonide Moguy, who directed me in my very first picture, ‘Tomorrow Is Too Late.’ Moguy, who is a French director, saw me one night in the home of friends. Instantly he said to his wife, ‘There is the girl for my picture!’ In the park where I often walked with my girl friends, a lot of people were often asking me, ‘Why aren’t you in the films?’ I told them, ‘I don’t want to be.’ I meant this. I was happily studying at my art school. I didn’t ever want to be in the movies, I wanted to concentrate on art.

“But then, this night, Moguy asked my mother, please, to bring me to his house so he could talk to me about his picture. And, although my father said violently, ‘NO!’ to the very idea of a film career for me, my mother—who had always dreamed of being an actress and had been a very successful actress in amateur productions—encouraged me to take this chance now it had come.

“The day we went to his home Moguy took me in a room to talk and I had never been alone with a man before and I was scared. I sat, I remember,” Pier smiled, “on the small point of the chair. So then he told me the story of ‘Tomorrow Is Too Late’ and the story was all about a girl who is kissed by a boy and thinks she is going to have a baby. And as Moguy was telling me this story he suddenly sees that I, too, believe the same as this girl, that his story and my story are the same story. He stopped then.

“ ‘Anna Maria,’ he said, ‘when a boy kisses a girl, she does not have a baby.’

“ ‘Oh, really, is that so?’

“ ‘It is so. It is not by kissing a boy that a girl has a baby.’

“We went home, soon after, in the bus. In the bus my mother asks, ‘What is the matter with you? You look strange.’ I think I did. I felt like a new life had opened to me. I wasn’t afraid to stop being a child. I didn’t want to stop, but—I wasn’t afraid any more.

“So then, all at once, I am in the films and growing up. But not enough. I was so embarrassed when on the set in front of the cameras we started the scene in which the boy is to kiss me.

“We stayed two days on that set,” Pier said and laughed. “I didn’t want him to kiss me. A little boy of sixteen he was, too, and I was now seventeen!

“ ‘Please, Anna Maria,’ the boy would say so nicely, ‘let me kiss you.’

“Please, Anna Maria,’ Moguy would say, and the cameramen would say, ‘let him kiss you)’

“ ‘No, no,’ I would whisper.

“When I knew I could delay no longer, ‘Turn around then, turn around,’ I said to Moguy and the cameramen. ‘Turn your backs on me!’

“ ‘How can we turn our backs,’ they asked, ‘when we have to photograph you?’

“So then I let him kiss me. It was my first kiss. At seventeen, my first kiss and—I fainted completely!

“The worst of my growing pains came, it is plain to see, from my wanting not to grow up, from my fighting, which was fierce, to stay a child.

“Another part of my growing up started, so sadly it hurts me to tell of it, when my father died three years ago. Before he died, he took me in his room, only me, and he said, ‘I am going to go. You, who are so like me, are going to take care of the family. Please have your mother always with you. You are the boss.’

“Thinking then for the first time, really, of shouldering responsibility was, for me, very hard. So hard for me, who had never bought a dress or ordered groceries or done any practical thing at all, to take such responsibility as signing papers at the consulate in Rome. Papers that had to be signed before we left for America, which explained I could take care of my mother and sisters or I would not have been permitted to bring them with me.

“I did all the signings and other of the business things there are to do at such heavy-hearted times. Yet even after I got to America, to Hollywood, I had still my hands in front of me, in front of my face. . . .

“Here in America, in Hollywood, Kirk Douglas was the first to help me. Kirk, who is my dear friend, but only my friend and not in love with me nor I with him, helped me more, I think, than anyone in America.

“He started helping me when we were working together in the circus sequences of the film, ‘The Story of Three Loves,’ and I, who still love everybody and think everybody loves me, was always saying, ‘I love her!’ and ‘Oh, I love him!’ And I was kissing everybody. And Kirk told me, ‘Please don’t throw yourself at people like a baby. You can’t love everybody. If you do,’ he said, ‘you will make too many people unhappy. You have to love one person,’ he said. ‘You have to grow up.’

“But although I listened, and believed him, I kept on saying ‘I love her!’ and ‘I love him!’ the same way I love hot dogs and roller coasters and meeting movie stars and cashmere sweaters and boogie-woogie and classical music and the records of Perry Como and Frank Sinatra.

“So just last year, even though we no longer see each other very often, Kirk gave me a tiny doll-house living room, all silver. The tiny, tiny furniture silver, too.

“ ‘See, Pier,’ he said. ‘It is nice to have little things to look at, but you are too big to sit in this little room. Just look at it sometimes.’

“I knew what he meant.

“It was in Palestine, when he was making ‘The Juggler’ there, that Kirk found the tiny doll-house living room, no bigger than a fifty-cent piece, and bought it for me. Such a delicate thing it is and such a delicate way to remind me I am not a little child any longer. . . .

“Debbie Reynolds, who is my best American girl friend, she has helped me a lot. She talked to me for hours. About boys and dates and things. I thought boys went out with you for yourself alone. Debbie told me they do it for other reasons. Sometimes for publicity, she said. She gave me warnings, too. ‘A boy who dates a girl he knows has never been out before is liable,’ she said, ‘to try anything! You shouldn’t go out with him,’ she said of one boy who asked me to date. ‘I know what he is like.’ ”

Pier has not had many date problems, however, because—as she explained—prior to June 19, 1953, she was never allowed to go out with a boy unless her mother went with her—which was something of a problem and, Pier admits, one of her growing pains.

“To American boys, the word chaperon,” she laughed, “is like the word scat to a little kitten. “You see,’ I would try hard to explain, ‘my mother—well, we just came from Italy so, if you will please understand, she will be with us . . .’ Some understood and some didn’t. ‘Oh what you mean,’ those who didn’t would say, ‘this is out of this world!’ So they disappear for a time, but then,” Pier shrugged slim shoulders, “they come back!” she said.

“But, yes, it was a problem. An older person there, no matter how you love her, it is always different.

“When Gene Kelly and I were working together in ‘The Devil Makes Three’ in Germany, Gene helped me. He knew my mother is so very strict and he said to her, ‘In my opinion, you are very wrong, Mrs. Pierangeli, to be so strict. I know how you feel. I have a daughter of my own. But if a girl wants to do something, she will do it. Let her be free, not afraid with men.’ One evening Gene and his wife and our director and some others all went to a restaurant in Berlin. Gene taught me to waltz and to fox trot and on this evening, the first time I had ever been out without my mother, I was relaxed with men.

“Leslie Caron, who has been married,” Pier said with the slight awe of the unmarried for the married girl, “she helped me, too. She came to my house and we play records and we talk. She is very wise in a way that is sweet and good.

“But it was only last year that I really grew up. I knew I was grown up when my mother let me go out on a date unchaperoned. It was in London where we were staying while I was working in ‘Flame and the Flesh.’

“ ‘You can stay out now,’ my mother said, ‘as long as you want.’ I went out that evening for supper with Carlos Thompson, who is playing opposite me in the picture and—at eleven o’clock I was home!

“I know I am grown up now when I have to go to the lawyer, all by myself, and sign things. All the contract things.

“I know it, and I feel a little tight in my throat when my mother tells me, ‘If you want to get married, I will express my opinions, but the decision is yours.’

“Until last year I didn’t wear any make-up at all. Now I wear just a little lipstick, but of no color, only to keep my lips smooth and moist. Until last year I wore only flats on my feet, now I wear high heels—little, beautiful spiky ones! Until that date in June, nineteen fifty-three, I always wore my hair down and the necks of my dresses up. Now I sometimes wear my hair up and my neckline down. I have now more sophisticated dresses, a few, and since I am twenty-one my waistline, which was twenty-three, is also twenty-one!

“I have not been in love, but now I think of love, the kind of love you talk about, the kind of love Debbie and I talk about and dream about and the peace of mind that will come, when it comes, and the peace in the heart.

“The things that happen to you are all a part,” Pier said, “of growing up. Joys help you to grow the same way sunshine and rainwater help flowers to grow. Suffering is a part of growing up, too, and I have done quite a lot of that. And I will do more of it. And more of the joyous things, too, because as long as we live things and people and feelings keep happening to us.

“So perhaps we never,” Pier said wistfully, “really stop growing up. Perhaps we are always children with things to learn to hope for. . . .

“Only we must not play with toys any more. We must have what is called the ‘mature mind.’ We must take our hands from in front of our eyes and face responsibility.

“This is why the little silver room is a symbol. And I do not only look at it sometimes, as Kirk asked me to do, but all the time because, wherever I go, the little silver room goes with me. To remind me. . . .”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954

No Comments