Elvis Presley’ Errand Of Death

A ear swings out of control, the tires squeal, the brakes screech, ifs all just in a moment really, and then, a man is dead, a life is taken accidentally, irrevocably.

He was not a famous man. Outside of his family and friends, nobody ever heard of him. But he had had his hopes and his dreams and his plans, and now they were all cut off. He was dead, and Elvis Presley unfortunately, unhappily figured in his death—the death of a man he never knew.

His name was Harvey E. Hensling. He was forty-five years old and lived in Glendale, California. He was a man of modest means, a gardener. That is all that is known of him.

Elvis also lives in California, in the “millionaire’s paradise,” Bel Air. He is rich, famous and young. But he would gladly give it all up if only Harvey Hensling could be alive today . . .

Foreboding clouds appeared black and ugly in the sky over Southern California that morning of Hensling’s last day on earth. The weatherman had predicted rain, and it hovered in the clouds, sometimes almost coming down and then not. Elvis was on his way to work. But something was wrong. He sensed it as he reported to the set. He didn’t feel up to par. It was the final day’s shooting of “Fun in Acapulco.” Soon he would be free to return home, to his beloved Memphis. There he could enjoy the freedom of strolling down a Street without the fear of having his clothes ripped to shreds by souvenir-minded fans. There he could dine in a restaurant. In all of Presley’s days in Hollywood he has only dined out twice. Both times nearly had the riot squad out in full force. And even knowing he’d soon be home, he still felt that something was wrong in his world.

In “Fun in Acapulco” he plays a trapeze artist who suffers from vertigo following a fatal accident to his brother, a member of the act. Elvis misses a routine catch in the air and the brother falls to his death. Elvis feels responsible. And as a result he’s unable to conquer heights again.

Director Richard Thorpe and other movie brass wanted Elvis to use a double for the final day’s filming. What remained lo be shot was the sequence where Elvis accidentally lets his brother fail to the hard circus floor.

By now it was raining outside. Several stage hands around the set noticed that Elvis appeared unnerved as he stepped from his dressing room. They knew that he had done more dangerous stunts than swinging from a trapeze. They were puzzled by his uneasiness.

As always, The Boys, numbering an even dozen of Elvis’ buddies from his hometown, weren’t far from his side. Although Elvis has all of them on his payroll, he thinks of them as brothers. They go where he goes. They do what he does.

One of them, Red West, married Presley’s secretary a year ago. Elvis was best man. Most of them grew up with Elvis in Memphis. On this day the Presley Boys appeared as happy as ever. Some of them were playing cards outside the dressing rooms. Others were drinking coffee.

Now Elvis was ready to work. “If we get this in one take we can be finished with the film by noon,” Thorpe informed Elvis. “Just take your time, though, and be careful.” Apparently the director’s words were enough to break Elvis’ tension. He smiled, and even was laughing as he climbed a ladder to the trapeze platform, some twenty feet above the floor. Just in case he slipped during the performance there was a net beneath. However, it still took a keen element of skill since not all the areas Elvis would swing over were covered.

“Remember,” Thorpe called to his star. “Take no chances.”

On another platform across the movie- made arena stood Jerry Summers. Jerry is a veteran Hollywood stuntman, and was set to take the “fatal” fail called for in the script. He plays the brother. Jerry was wearing white circus tights and in many ways resembled Presley. From a distance, the two could be mistaken for twins when dressed alike.

They were having trouble getting the proper lighting for the scene. And, waiting, Elvis stood motionless on the platform. Suddenly a quiver of fear swept over him. The expression on his face changed. Obviously, his thoughts were thousands of miles away. Years away.

And they were all thoughts of death.

Death already had played a tragic role in Elvis’ life. More than two decades ago his mother gave birth to twin boys. The first to be born died only minutes after entering this world. Elvis lived. And why was he picked to live? This he could never figure out. He finally stopped trying. Only God knows, Elvis told himself over and over again.

Now, in a way, it was painful to him that he would be responsible for his brother’s death, even though it was only for a movie. Elvis grabbed the trapeze swing on the platform. He saw that they were about ready to start filming. Oddly, he felt no fear himself. Only the fear of past tragedies. He recalled losing the dearest woman in his life to the clutches of the unknown. When his mother died a few years ago, he wept for days. There’s still emptiness in his heart over her death.

The red stage light burst into brightness as Thorpe called for action. Elvis confidently pushed himself off into space, holding the swing bar tightly in his hands. He swung to and fro so professionally that one would think he belonged with Barnum and Bailey instead of Paramount.

As the cameras were grinding, Elvis looped his legs over the bar, his arms and torso swinging free. Now the stuntman was swinging on his trapeze. The fatal meeting was only seconds away. Now Elvis began to think of how he was robbed by death of another real brother.

When his father, Vernon Presley, had married again Elvis was pleased. He knew how much his father had loved his mother. But loneliness, he knew, can be worse than death. So when his father fell in love and married again, Elvis couldn’t have been happier. And then he was hap- pier when the second Mrs. Presley announced she was expecting a child. He just knew he would soon have a stepbrother. Tragedy struck again when Mrs. Presley suffered a miscarriage. Elvis was heartbroken. At birth he had been denied a brother—and now he was to be denied a brother again.

Across town, in secluded Bel-Air, light rain was falling as Harvey Hensling, the gardener, was taking his morning coffee break. He didn’t mind the rain. It only made the flowers and shrubs greener and more beautiful. Gardening really was an art in this exclusive neighborhood. all the homes in Bel-Air ar e owned either by celebrities or men who have struck it rich, and the landscaping is magnificent.

Hensling was sipping his coffee beside his truck only two blocks from w her e Elvis leases a sprawling estate. Several times he had passed Presley’s home and admired the landscaping. He thought it would be wonderful to take care of Presley’s gardens. But another gardener had been hired, so Hensling never had set foot on the estate.

Now coffee time was over. He had to start on his major chore of the day, trimming a high hedge on Bel-Air Road not far from the swank Bel-Air Hotel. He picked up his shears and started to work.

Just then at Paramount Studios Elvis reached out on the trapeze to catch the stuntman as he leaped free from his swing. Just as in the script, Elvis missed the catch by inches and Summers went screaming to his fate. Actually, the net broke his fail out of camera range. However, moviegoers will see the brother hit the arena floor with a crunch. Then they’ll see Elvis broken up with grief.

The director smiled. “That’s a print,” he called. “Elvis, you were great. For you the picture is over. And it’s before noon, too, just like I promised.”

Elvis, however, was still moody. He quickly went to his dressing room, and slammed the door. Meanwhile, the Presley Boys frolicked about. One pretended he had a firecracker. He lit a wad of paper and tossed it into a group of extras. They scattered hurriedly.

Just then as Elvis was ready to leave the studio and go home to relax, he was summoned to the telephone on the set.

It was the publicity department. Since he had finished the film ahead of schedule they wanted him to spend the afternoon posing for publicity photographs. He didn’t feel up to having bright lights popped into his eyes the rest of the day. However, it had to be done and if he got it over with now he wouldn’t have to report back to the studio the next day. So he agreed.

Suddenly he remembered . . . he didn’t have a good pair of slacks and a sport shirt with him. Knowing he was only supposed to wear tights for the last scene, he had not bothered with his outfit that morning. And all the clothes in his dressing room had been moved to his home the previous day.

He’d have to send one of the boys to his home to get his clothes. It would take less than an hour and he could have lunch while he was waiting. So Elvis called over to Richard Davis Jr., who was watching a card game.

“Do me a favor, Dick,” Elvis said. “Take the station wagon and drive to the house. Pick up some clothes for me to wear this afternoon. I called the house so they’ll be laid out for you.”

The rain had stopped as Dick slid behind the wheel of Elvis’ white station wagon to go on the errand. He waved at the studio guard as he drove out the gate and made a right on Melrose Boulevard, heading for Beverly Hills and Bel-Air.

Hensling was busily trimming the hedge when the white station wagon passed him. He was so engrossed in his work he took no notice of the car. And Dick didn’t notice the gardener as he drove up the winding and narrow Bel-Air Road. There are no sidewalks in Bel-Air and some of the shrubbery borders the road. Dick quickly but carefully carried out the first half of his assignment. He placed the shirt and slacks in the car and prepared for the return trip to Paramount.

He never made it back.

Only two blocks from the house, Dick rounded a curve in the road. What happened in the next few seconds is now a nightmare to both Dick and Elvis.

The police summed it up this way: Just as the station wagon rounded the curve, Hensling for some reason—perhaps to admire his work—stepped back from the hedge onto the road. Dick didn’t have time to stop, although he slammed on the brakes with full force.

The right headlight of the car plowed into the gardener with a crunch. Suddenly he was flying through the air, his body bouncing with a thud on the pavement yards away. The gardener’s Clipper s had flown high over the hedge.

From that moment on Davis remembered little of what happened. The shock proved too much. He forgot the ambulance rushing the critically injured man to the hospital. (He was still breathing but in a deep coma.) He forgot the questions of the police.

Meanwhile, Elvis was waiting for Dick. It wasn’t like him to take so much time, Elvis thought. It had been over an hour since he left on the errand. Elvis began to worry. Something must have happened. A moment later his fears were confirmed. A servant at the house called to explain what happened.

“Is the man alive?” Elvis wanted to know first. “How’s Dick?” was the next question. When Elvis was told the man was in critical condition something snapped within him. He burst into tears.

“I’ll be right home,” El said in a cracking voice. “Tell Dick not to worry.”

Greatly alarmed. Elvis raced out of the studio. His face pale. His hands trembling.

The man can’t die . . . it must be a nightmare. Some kind of horrible dream. It didn’t happen . . . how terrible for Dick . . . how terrible for the man’s family. He could think of nothing else but the overwhelming tragedy as he was driven home by another pal.

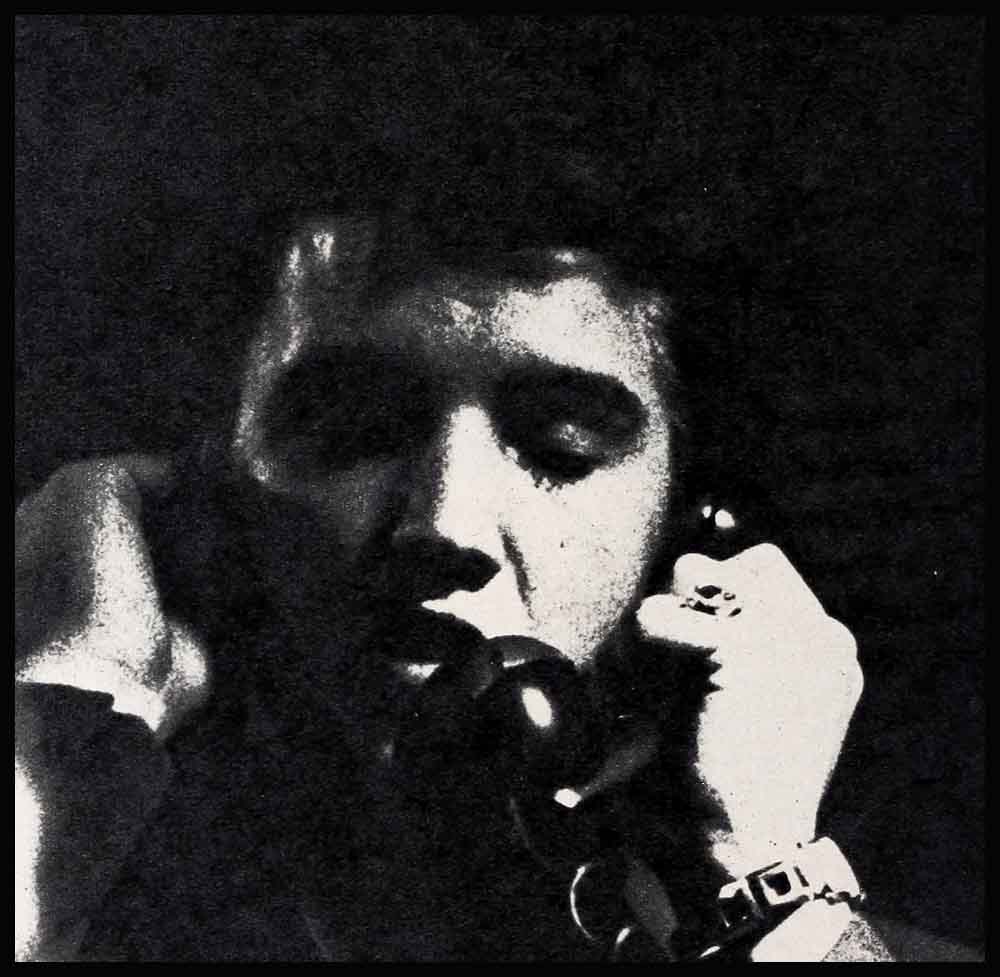

He stumbled into his home and grabbed the telephone to call the emergency hospital. The gardener was still alive, but his chance of pulling through was slim. He had suffered broken bones and a severe concussion. He had lost a lot of blood, too.

“I want to be notified immediately if there is any change in his condition,” Elvis told the nurse.

He was still trembling and at a loss for words. Every so often he would pat Dick on the shoulder and try to cheer him up. It was no use, though. Outside in the driveway was more sickening evidence of the tragedy. The headlight on the station wagon was broken. The fender crushed.

The silence of waiting became horrifying. Elvis hadn’t felt so helpless since his mother died. If he could just do something that would help Hensling. But the life of the gardener was not Elvis’ to save. Only a Higher Power could help the dying man now.

Elvis was about to phone the hospital again when it rang. once . . . twice . . . three times. There was something ominous about the sound. Neither Elvis nor Dick made a move to answer it.

On the fourth ring Elvis grabbed it. It was bad news. Harvey Hensling was dead.

Elvis gasped. Why did it have to hap- pen? Why did death have to play another role in his life?

Dick held his hands to his face in sorrow, in disbelief. This was the kind of thing you read about. The kind of thing that always happens to the other guy.

Like he had in past sorrows, Elvis engulfed himself in solitude for the rest of the day. He and Dick just sat, staring at nothing. Thinking of a man they never knew or would know. Of a man who was dead.

Somehow, Elvis thought, it must have been fate. Hadn’t he felt moody and apprehensive that morning? Hadn’t he re- lived memories of the sad past? And now there was the horrible reality of the present.

If only he hadn’t sent Dick for the clothes . . . if only he hadn’t sent him on an errand of death. Could he ever forget the hand he played in a man’s death? No, he knew he never could. He knew the memory would live in him as long as he lives. For, when Harvey Hensling died, something in Elvis Presley died, too.

—THOMAS WHEATON

El’s in Para’s “Fun in Acapulco.” M-G-M’s “It Happened at the World’s Fair.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1963