They’re Expecting A Living Doll

“When Dr. Krohn told me I was going to have a baby,” says Jean Simmons, “I floated out of his office like a sleepwalker. And when, driving home, I’d reached a more rational state, I said to myself, ‘Jeannie, old girl, one thing you’re not going to do is tell a living soul—not for months and months.’ Nobody, but Jimmy.” (Jimmy is husband Stewart Granger’s given name.)

“So,” continued Jean, her high-voltage eyes suddenly merry, “I opened the door, and there were Jamie and Lindsay—Jimmy’s children who came over from England to live with us permanently—playing with the poodles, Old Beau and Young Bess; the Tibetan water spaniel, Me-Too; and the twin Siamese cats, both called Traybert because we can’t tell which is which.

‘‘No sooner had I said ‘Hello’ than I found myself shouting, ‘I’ve got news for you!’ (This is an expression the children had picked up and used ad nauseam.) ‘I’m going to have a baby!’

“ ‘A baby! A baby!’ cried both children. Then they rushed at me with glad shouts, knocking me down, and soon children, cats, yipping dogs were treading on my stomach, rolling me over and over like a ball of yarn, pounding me and screaming for joy.

“When we’d unraveled ourselves,” Jean added, laughing all over again at the memory, “I sent a cable to Jimmy. He was in London, doing added scenes for ‘Bhowani Junction.’ I didn’t dare phone him because, before he left, we’d had a solemn discussion on our high-flying budget, what with buying the new house and all. But Jimmy phoned from London immediately, saying ‘Blast the budget,’ and we talked and talked. Right then, we decided that our best friends, Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Wilding, would be asked to be godparents.

“ ‘It will be a girl, I’m sure,’ I told Jimmy.

“ ‘It will be a boy, I’m certain of it,’ he told me.

“Well, come next August, one of us will be right.”

Still resolved not to tell anyone else the exciting news, Jean proceeded the next morning on the set of “Hilda Crane” to make with the “I’ve got news for you” bit to everyone from co-stars Guy Madison and Jean Pierre Aumont right down the line to the electricians. Within hours, the columnists were calling, chiding her for not giving them “exclusives” about the baby. “But I didn’t think that was news,” Jean said, in her little-girl voice. “And, anyway, how did you know about it? I’m keeping it a secret for months and months.”

It was as impossible for Jean to keep this secret as to stop smiling. Today, no matter how the conversation starts out, it winds up with the Blessed Event. “I hope,” Jean laughs, “that my friends will gag me if I become too sickly sweet and sentimental. I know it’s been said that a bore is a man who, when you ask him how he is, tells you. But that goes triple for a woman who’s going to have a baby. Now, that’s enough baby talk,” she will say briskly. And, in a few minutes, mysteriously enough, the conversation is back to baby talk.

As the beauteous brunette explains, “When a friend tells me she’s going to have a baby, I think, ‘Well, that’s jolly nice, that’s just fine,’ and I’m ready to go on to some other topic. But when you, yourself, are being followed by some bird that could be the stork, then it’s the most earth-shattering thing. You feel you’re having the only baby in all the world. You can’t think of anything else, and suddenly every day is like Christmas with something wonderful to look forward to. There’s a kind of undercurrent of excitement. You feel so special, so complete. I’d say it all boils down to this: Every woman should have a baby.”

After she finished “Hilda Crane,” Jean luxuriated at home for several lazy weeks. Then one day she returned to the 20th lot for lunch. Her table in the commissary was soon surrounded by friends—directors, actors, executive, extras—for Jean Simmons has the rare ability to inspire affection in everyone who knows her. Months earlier, when she returned to make her last film before her temporary retirement, she’d been greeted by a huge Welcome Home banner. And halfway through the shooting she’d been given a combined birthday party-baby shower by the crew. “Don’t you have a nice hefty part for a pregnant lady?” she cajoled Philip Dunne, the director. “Perhaps a whole film, set in a maternity ward, and titled ‘From Here to Maternity.’ ”

As reporters well know, you can get in a rut writing about Jean Simmons because you always end up telling what a genuinely gracious, nice girl she is. That day she looked wonderfully healthy and happy. Her olive skin had been bronzed by the sun, her enormous, gold-flecked hazel eyes were shining, her close-cropped brown hair jaggedly framed her little-girl face. She wore a simple, full-skirted pink and white checked tissue gingham dress, with white embroidery outlining the collar. The back hung loosely; the front was gathered in by a thin belt. “I bought it at the Jax sports shop. It’s not a maternity dress at all,” Jean explained, “and later I’ll wear it full in front and belted at the back.”

Jean has no intention of disobeying even one rule laid down by her obstetrician. He’d explained to her that diet and weight control are the two most important factors in a healthy pregnancy. He noted her weight was 120 and asked what she considered her ideal weight. Jean said 115, and Dr. Krohn advised her to gain no more than twenty pounds during her pregnancy. He promised that if she follows his diet list and post-pregnancy exercises, she’ll regain her ideal figure shortly after the baby is born. Wise Jean’s relationship with her obstetrician resembles that of obedient child and highly-respected teacher. “If,” she explains, “I’m a little over the weight I should be, I’m told about it, and I cut down before my next visit.”

Jean’s doctor doesn’t believe in formal exercise during pregnancy, but he did strongly advise that she continue her daily swimming and walk as much as possible every day.

She admits that she never felt better in her life. She hasn’t had any morning discomfort at all; she’d been told by friends that the months would drag, but they haven’t; she’d been warned about depressions and irritations over small things and that she’d develop strange tastes for exotic foods at 2 a.m. “A few mornings,” Jean says, “I woke up and I could swear I smelled fried bread cooking, just as I had when I was a child in London. This is a breakfast dish common there—large slices of bread popped into sizzling bacon grease, like an egg. Um, um, so wonderful. Finally, I told Jimmy and he said, ‘I’m going to make it for you three times today. Eat your fill and then you’ll forget about it. It’s too fattening and not good for you.’” After a day of heavenly fried bread, Jean was content to follow her doctor’s diet list.

In past times, when Jimmy would return from his long and frequent location trips abroad, he’d look at Jean tenderly and say: “I see I’ve got to ‘pork’ you up a bit,” and proceed to tempt her flagging appetite with gourmet dishes, for Jimmy is a noted chef and connoisseur of fine food. But today, the whole Granger clan is diet-conscious. They adore steaks grilled on the outdoor barbecue, without sauces “It’s a crime,” Jimmy says, “to tamper with the natural flavor of a superb steak.’ Jean agrees, and she agreed also when Jimmy noted that Lindsay and Jamie were gaining too much weight on the rich American food they adored. So now ice cream and fancy desserts are taboo, except on festive occasions.

Jean feels that her simple, doctor-prescribed diet is a small price to pay for a healthy, happy pregnancy. “Also, it’s a good thing I haven’t developed a craving for cockles and winkles at this time,” she says. “Because Jimmy would have to fly to London to get them.” Jean sighed ecstatically. “When I was a kid, I received sixpence a week as an allowance. And I’d fret myself silly deciding how I’d spend it—on winkles or cockles. Do you know winkles? They’re lovely little shellfish so tiny you have to dig them out of the shell with a pin. They’re sold on the streets in little paper bags just as you get hot roasted peanuts here. Jimmy says it’s a very low taste on my part. But then he loves bubble-and-squeak, which is made from cold potatoes, boiled cabbage and bacon fat. Sounds revolting—until you’ve tasted it. Jimmy’s mad for kippers, too, although they smell up the whole house when he grills them.”

Jean took a cigarette from a beautiful gold cigarette case, another of the thoughtful gifts her husband had brought her from abroad. It’s a very old box and Jimmy found an even older tiny gold medallion of Catherine de Medici for the cover. “Eight cigarettes a day—no more,” Jean explained, “on doctor’s orders. I mind that a bit more than giving up the before-dinner cocktail or the glass of Budweiser in the evening to drink while listening to a TV announcer extol a rival beer. (It tastes better that way.)”

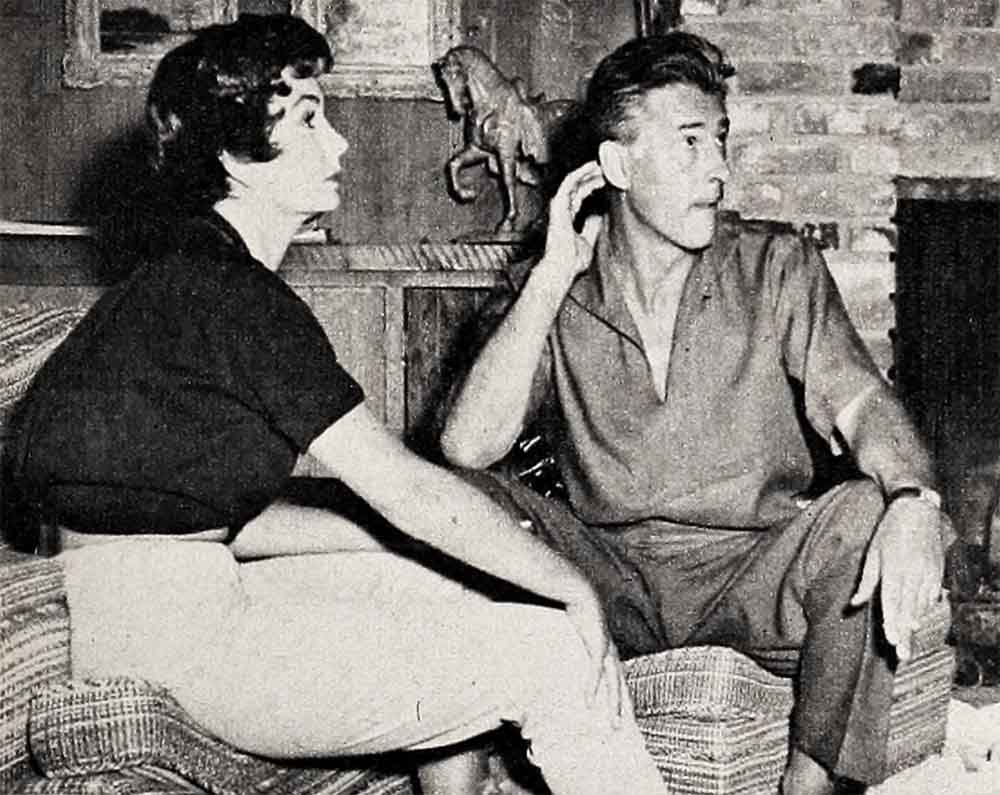

Like any other newly expectant mother, Jean is lost in the wonderment of her new role, very happy and yet a bit apprehensive. Will she be frightened the first time she bathes an infant? How does one know whether a baby cries to exercise his lungs or because he is in pain? all these questions are discussed as Jean and Jimmy spend quiet evenings together, savoring the anticipation of parenthood.

Jimmy reassures Jean, for he’s an old hand at diapering and fixing formulas. Son Jamie, he remembers, hardly ever cried, but Lindsay was a bawler. And he found that holding the baby quite closely, letting her feel the warmth and security of a parent, stilled her. Babies, he knows, needn’t be handled like fragile glass; they’re tough creatures and very smart.

“Both Jimmy and I feel very strongly about leaving a baby with a Nanny,” Jean explains. “Naturally, we’ll have a nurse while I’m working, but my freelance status makes it possible to delay accepting a picture until I want to. And I plan to stay with the baby a long time before I do another film, though Jimmy, looking thunderous, says, I’ll give you just one week after the baby is born, Old Girl, and then, it’s back to the coal mines for you!’ But he doesn’t mean it. When we hear of Nannies who tell the parent when they may visit the baby, we bot know we’d send such a nurse packing. With a baby turned over completely to nurse, it’s just like having an unread boo in the house, one you never get to know Baby smiles and shows his first tooth to Nanny, waves his arms and says bye-bye takes his first step and topples into Nanny’s arms. All agog, she phone Mommy at the studio. Mommy wails to high heaven, feeling cheated, and with good reason. Having children does not make one a mother. Only mothering does—that is, experiencing a child’s life through constant association. That’s what I plan for our baby, and that’s why I’m going to make only one film a year. I think of the baby as ‘she’ all the time. I’ve even made bets with everybody that I’ll have a girl, and even hope to call he Tracy. But, really, a boy will be just a welcome. All one needs is patience to know the answer.”

As lovely Jean Simmons talks, her clear hazel eyes have a placid quality, a contented quiet. She tells of still another matter under discussion, and that is American citizenship. Since the baby will be an American, it’s very likely that Jean and Jimmy will take steps to follow. For as Jimmy says, “When you have children common citizenship is terribly important. Children must feel that their parents loyalties are exactly like their own.”

In Jean’s first days as an expectant mama, she eagerly sought all the books she could find on babies, even met Jimmy on his return from London with a copy of Dr. Spock’s famous book on infant cart in her hand. Jimmy gave her his gift—s delicate porcelain figurine of mother and child—and she pressed the book in his hands. “Not an even exchange,” grinned Jimmy. Although Jean read all the books she’d collected, they didn’t help because they dealt with such far-off subjects as formulas, colic and the like. Jean wanted a list of pre-natal symptoms. And when she found them, she realized she had none of them. So the books are stored away now. “I don’t think it’s a good idea, anyway,” she says, “to know all the gory clinical facts of maternity. I have a doctor and that’s his job. I know I don’t believe in Caesarean section unless it’s medically necessary, and I don’t believe in having a baby at home. I’ll take the hospital where everything necessary is at hand. All I want is a healthy baby.”

Jean has wanted that for all the five years of her marriage. While in London last year, she was a little startled to see newspaper headlines: “Jean Simmons Wants Baby.” “I didn’t exactly say it in headlines,” she giggles, “but when reporters had asked me, I told them.” No one but Jimmy and close friends knew how much Jean had longed for a child. It was the only area in her life in which she felt deprived. Neither Jimmy’s love nor her own soaring career could fill this special emptiness deep within her. And when Liz Taylor and other mothers came to visit her with their children in tow, Jean could scarcely mask her heartache.

All of that unhappiness has ended now. The ache was eased somewhat when Jimmy’s children by his first wife, British actress Elspeth March, came to live with the Grangers last fail. They’d visited their father on school vacations, and had had frequent reunions while he was in London on location. And when Jimmy found their mother in poor health, he prevailed on her to allow the children to leave London. Full of vitality, Jamie is a very large and healthy eleven-year-old. Daughter Lindsay Jean is a blue-eyed, golden-haired, equally active tomboy of ten.

“Friends wondered,” says Jean, “how I’d get on with two vigorous youngsters, my career and a new baby on the way. It’s been wonderful. Jamie and Lindsay have made a quick adjustment to the American way of life and they treat me like an older sister and call me ‘Jeannie.’ I’m living my childhood all over in them. They both adore blood and thunder, in movies, in books, just as I did.”

After Jamie and Lindsay arrived, the Grangers soon realized that their isolated, mountain crow’s nest, with only two bedrooms, was too small and unsuitable for the expanded family. So they sold it and all the furniture and bought a six-bedroom modern house on an acre of wooded rolling slopes in fashionable Bel-Air. There is a striking view of the ocean and, nearer at hand, a handsome tiled swimming pool. And there are children in all the near-by homes, a fine private school across the road, a film projector in the den which can show movies even in CinemaScope. There is also a complete wing for Jamie and Lindsay, with pine-panelled bedrooms, a kitchen, barbecue, ice-cream bar, where the youngsters can have friends over for weekends and roughhouse to their hearts’ content.

Jean is thriving on lazy content these days, even though the house is still undergoing changes and the nursery is yet to be furnished. The new house was bought furnished, but Jimmy, a perfectionist and a man of impeccable taste, is weeding out furniture and replacing it with custom-built Robsjohn-Gibbings modern pieces. He’s also occupied with the gardens and grounds—planting scores of fruit trees, shrubs and flowers and supervising the installation of huge boxed shade trees at strategic spots, just as he made a garden of Eden at the hare mountain top of their former home.

Indoors, Jimmy has found just the right backgrounds for his superb art collection—the Augustus John and the Sir Matthew Smith paintings; the two paintings of Jean in entirely different moods done by the French artist, Domergue; the Ming porcelains; magnificent Tang horses; Rodin and Jacob Epstein sculptures and Chinese ancient stone figures. Nor has he forgotten his fabulous collection of African mounted game trophies and game fish. “Some of our friends find Jimmy’s decoration overpowering,” confesses Jean, “but we love it.”

Heretofore, Jean has definitely not loved the kitchen. “Jimmy’s definition of chaos,” according to Jean, “is two eggs, one frying pan—and me. That’s not quite true. But isn’t it silly for an amateur to cook for an expert? Jimmy is so gifted in so many ways. Really, he’s a built-in, do-it-yourself kit. He used to do most of the cooking and I’d act as supply sergeant—and, I’m afraid, also as a thorn in his side. I’d taste everything and offer my opinion: ‘A shade too much salt.’ ‘Meat’s a tiny bit overcooked.’ That was to keep him down to earth. But now, with the children, who must have early dinner, we have a cook in the kitchen and Jimmy takes over only on cook’s night out.

“But I can cook,” Jean adds, hopefully. “Right now I’m best at cooking up the pets’ food. At least they can’t tell me if it’s good or not. But when the baby comes, I expect to graduate to stirring up Pablum and sieving the vegetables. And go on to taking over more duties and home responsibilities.”

Today, Jean Merilyn Simmons Granger has outgrown her role of “child bride.” A magnificent actress, well-wishers everywhere believe her greatest role will be “mother.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1956