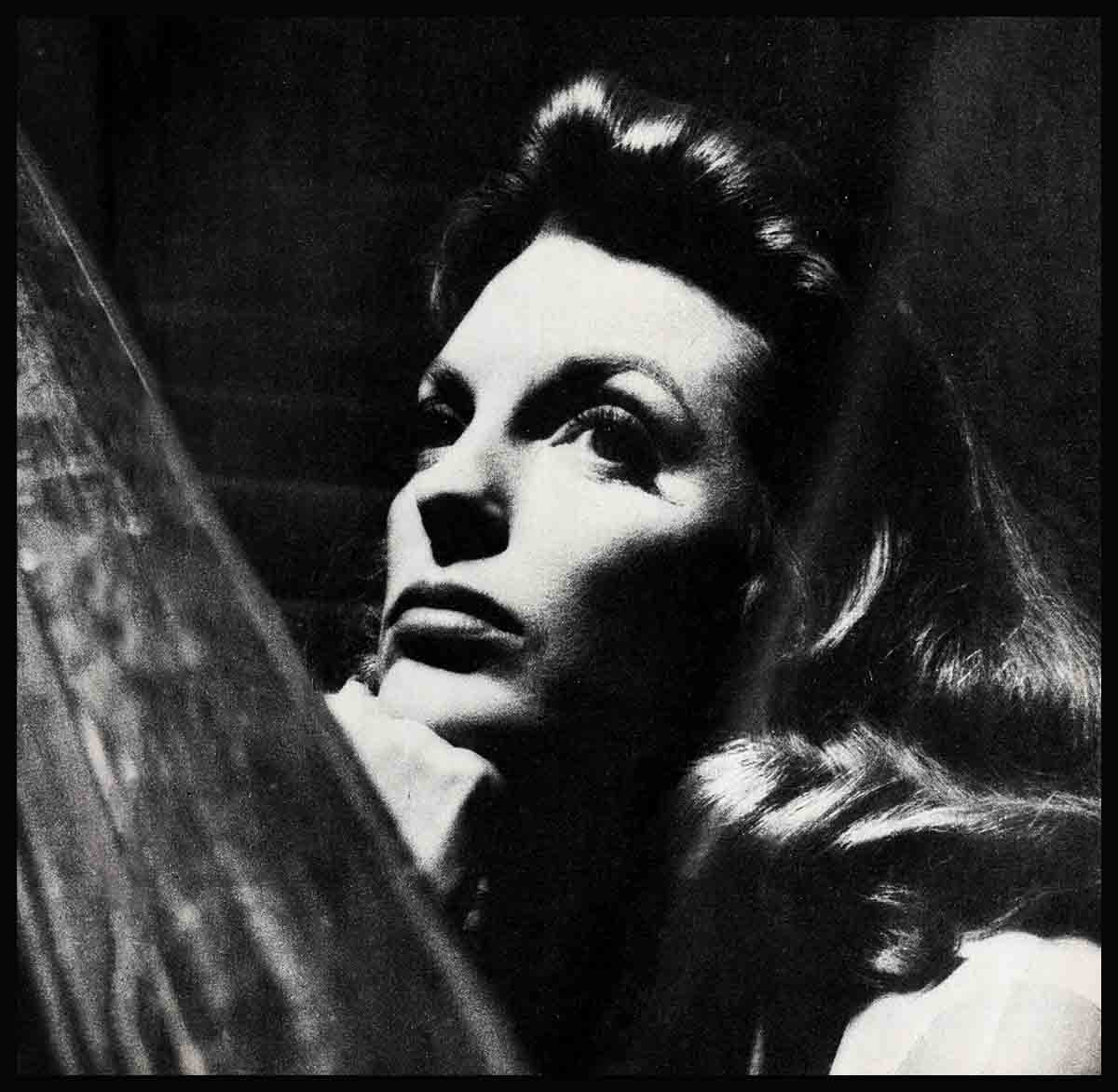

A Right To Sing The Blues—Julie London

“Blue was just the color of his eyes

Till he said, ‘goodbye love.’

Blue was just a ribbon for first prize

Till he said, ‘don’t cry, love.’

And blues were only torch songs

Fashioned for impulsive ingenues

But now I know . . .

Too well I know . . .

Too well I know the meaning of the blues.’’

In the middle of August, 1954 Julie London packed her bags and left for Europe. She wasn’t going anywhere, in the sense that people going someplace have a destination to get to. Julie didn’t have anywhere to go—there were just people and things she had to get away from.

It’s hard to say goodbye to a marriage, to six years of being with the one man you’ve ever loved, with whom you had two lovely, laughing-eyed little girls and experienced the joy and tenderness and togetherness of being a family. There are the things you remember, and they go with you long after your bags have been cleared by customs and the gangplank goes up. For your name was still Mrs. Jack Webb then, and you remember the time you and your husband were both unemployed during the first year of your marriage and you celebrated your first anniversary with a special cake and candles, but there was no cream for the coffee to go with it. You remember how happy you were the day the doctor told you your first baby was on the way, and how you rushed home to tell your husband, and how he set his shoulders back in that firm, determined way he had when you told him, and how he kept pacing up and down the room saying, “I’ve got to get something for the baby’s sake . . . I’ve got to.” And how he rushed into the house the next afternoon and threw his hat on the table saying, “I’ve just signed a thirteen-week contract on radio, honey,” and that’s how “Dragnet” was born.

You remembered the other things too: You remembered how happy you were when Stacy was delivered to you, a wisp of spring on a cold day in January. You remembered the thrill of getting dressed up in evening clothes to attend a movie premiére, and how proud you were when someone stopped your husband before he got to the entrance and said, “Say, aren’t you Jack Webb, of television?” and how you beamed when your husband said “Yes” and obligingly signed his first autograph. You remember the night he came home and said, “We’re moving. I just bought a house. A ten-room mansion!”

And then there were the other things you didn’t want to remember: how the houses got bigger and bigger and how your marriage got lonelier and lonelier till somewhere along the line it wasn’t a marriage at all.

Then one morning your husband left the house to go to the studio and didn’t come home for dinner. He didn’t come home the next night either—and when you called him the voice at the other end wasn’t hurt or angry or bitter, it was much worse: it was completely devoid of feeling.

“I just wanted to find out if you are coming home to dinner,” you said, trying to make the request sound casual, and the voice at your ear said “I don’t know.” Nights stretched into weeks then, and suddenly you knew that you and the children didn’t matter to him any more.

So you had to escape—to escape completely from everything and everyone you knew. You had to find some new meaning in living, to pick up the pieces and try to fit them into some kind of life that would make sense to yourself and your children, and most of all, you had to find yourself. You had to, if you were Julie London.

What Julie London did then was to return to Hollywood from Paris that fall and file suit for divorce. The settlement was generous: eighteen thousand dollars a year alimony, a trust fund of $100,000 for Julie and $50,000 for each of the children.

That should have settled everything, but it didn’t. Julie made a home for her two daughters in a big house on top of a hill, and started life over. But sometimes there seemed no place at all to get started. When day was over and dusk fell and other wives started to listen for the familiar sound of footsteps on the walk that meant their husbands were coming home to them, that was the time of day when Julie felt most lost and alone and lonely. She started searching for something to keep her busy, and found it: a career. And along the way, she found a new love too.

Julie London was born in Santa Rosa, California on September 26, 1926, and moved to San Bernardino with her family when she was two months old. Her parents were old-time vaudeville singers who had a radio program on a local station, and by the time she was three and a half Julie was performing professionally. She just wandered into the studio one day and started singing, and that was that! Her first paycheck, however, came from running an elevator in a department store. For when Julie was fifteen, she just went to the Personnel Department, boosted her age by a few years and landed the job. It marked the end of her high-school studies.

She was still running the elevator a few years later when one day a woman came over to Julie between stops and asked if she’d ever thought of being in pictures. Julie said “No,” she hadn’t. The woman was Sue Carol, Alan Ladd’s wife, and she was a talent agent. She whirled Julie around to some of the studios and landed her a few bit parts in movies. “It was funny. In pictures I made fifty dollars a day, then in between, I’d go back to the store and work for nineteen dollars a week.”

It was while she was working in the department store, too, that she met Jack Webb. He was a salesman there. They met, and dated and started going together steadily. Then Jack was called into the service, and when he got out, he settled in San Francisco and became a radio announcer. When he landed a role on radio’s “Pat Novak For Hire,” Julie would listen to him in Los Angeles. One night she dropped him a note to tell him how good she thought he was in the show.

At the time, she was about to finish her biggest role, “The Red House” and made plans to celebrate with a girl friend, a weekend in San Francisco. She was packing for the trip when the telephone rang. It was Jack, thanking her for her note and asking when if ever she would be coming to San Francisco. When she announced that she and her girl friend would be there that week-end, he arranged to meet them at the airport. Three hours after the plane landed, Julie and Jack Webb were engaged to be married.

Julie was happy then. For the next few months, Jack and she commuted between Los Angeles and San Francisco. That spring, Jack quit his job with the network and moved to Los Angeles permanently. That July, they were married. To Julie, it meant the start of living. For there was someone who needed her, wanted her and wanted her love. She’d give it gladly. Talking about it now, she says, “I didn’t care much about a career, but things were pretty rough financially when we were married. So I kept on working till we discovered we were going to have a baby. Jack tried to dream up an idea to make some money, and that’s when he created and sold “Dragnet.” By the time the baby was a few months old, the show was already on radio and doing so well that it was immediately on the ‘top ten’ popularity list. Then came television, and Jack’s huge success. On the twenty-ninth of November, 1952, I gave birth to a second little girl, Lisa. Two years later, Jack and I were divorced.

“I don’t care to talk about it too much,” Julie smiled, and sat up straight. “In a way, when I discuss this part of my life, it sounds to me now as though all that happened to someone else with someone else.”

However far away it all seems now, at the time the divorce left Julie pretty badly shaken. She’d never had much ego to start with, and had always been rather shy and introverted. But now she’d failed in the most important human relationship of all—marriage. The failure hit hard. Whatever security and confidence she’d managed to assemble in 26 years of living seemed to have been blown away with the winds of divorce. To fail in marriage seemed to fail as a human being. For she’d submerged her identity in the marriage, and when that went, she was nothing—just a shell of a person, with a long and lonely future in the offing. Then she met Bobby Troup, the well known composer-musician.

To Julie it was an accidental meeting in a small Hollywood restaurant where she and a friend were having dinner and Bobby Troup walked over to say “Hello” to her friend and was introduced. To Bobby, it wasn’t quite so accidental. He tells it this way: “I was playing the Celebrity Room and one night she walked in. I was singing a song and she walked by the bandstand and I thought, ‘That’s one of the most strikingly beautiful girls I’ve ever seen.’ Fortunately, I knew the girl she was with, and I thought, ‘I can easily sit down at the table and get introduced.’ So I did. And I was.”

Afterward, at Julie’s house, someone started to play the piano, and impulsively, Julie started to sing along with it.

“She gassed me. She was that good,” Bobby says now.

He asked her for a date and spent the entire evening telling her she ought to sing professionally. But to Julie, whose confidence was gone, singing in front of people she didn’t know was unthinkable. To sing before an audience would be exposing her soul to the public, for all to see and hear. If they didn’t like her singing, it would mean they didn’t like her. She couldn’t take that chance.

For a year and a half Bobby Troup pleaded and cajoled and pressured, trying to convince her that she really had talent. The words fell on closed ears. One night he brought two record executives to the house to hear her sing. Julie took one look at them, said “Hello,” and then quietly disappeared into the bedroom. Why take the risk of exposing herself to defeat and shame? It was easier to hide while Bobby made excuses for her and the record executives said, “Well, if Miss London ever overcomes her mike fright, we’d like to listen to her.”

Once Bobby did manage to get her to the studio for a recording date and she sang four tunes in front of the microphone. But she was so nervous and frightened that the sounds that came out weren’t the real Julie at all. Her timing was off, her breathing was stilted, and the words were devoid of meaning. All she could see was the mike in front of her and the sound engineer taking the song onto the tracks. The company never released the records. Bobby was hugely disappointed, but to Julie it was a landmark. Her worst fears had been realized. They’d heard her, they didn’t like her, and they didn’t want her. But she was still living And she could still sing, if she wanted to.

So Bobby tried another tack. If it was too difficult to sing before a mike with professional people passing judgment on her, why not sing in a night club, where people just wanted a little diversion, and to be entertained? Bobby was singing in a nightclub called the Encore then, and one evening they were having dinner across the street in a little place called Johnny Walsh’s 881 Club when Julie looked up from her steak and said, “You know, if I ever worked in a club, this is the one I’d like to be in.” Bobby whooped for joy and went to look up the manager, Johnny Walsh, who was a friend of his. Somehow he managed to talk Johnny into booking Julie without an audition.

For Julie, this was a big “first.” To the members of the audience in the nightclub she was going to be introduced as Julie London—not Mrs. Julie Webb—and she was going to make the grade or fail because she was herself, a girl who liked to sing the blues.

Now Julie remembers, “The night I opened, I thought I’d drop dead before the end of my first number. But somehow I opened my mouth and the words came out. The customers liked it.”

“Liked it? They loved it!” Bobby interjects. “Julie doesn’t tell you that she was held over for several weeks and that the place was packed every night. The room had never done that kind of consistent standing-room business before.”

But even success didn’t seem to help very much. When, one evening as they were leaving Bobby said, “What further proof do you need to know that you’re good?” she answered, “They’re just curiosity seekers. They just want to see what Jack Webb’s ex-wife could do.” Bobby looked at her and said nothing. It would take a few more good experiences and a little more applause before she’d be able to accept herself for what she was, a beautiful girl with talent.

Several of Bobby’s friends were about to start a new record company, Liberty Records, and casually Bobby suggested to them that Julie might be interested in making a record. They liked the idea. Together, Bobby and the record company executives worked out a plan. They’d get the studio ready, complete with engineers, sound men and technicians, but as far as Julie was concerned, to all intents and purposes this was to be nothing but a practice session. They were all to pretend that the record wasn’t to be cut till some time next week.

They started at eight o’clock in the evening, with Julie “practicing” her songs. Along about two o’clock the next morning, when Julie had unlimbered and the words going into the mike were soft and real and heart-rending, Bobbie signaled the sound technician, and he dropped the needle into the groove. By five o’clock in the morning, they had the first pressing of an album by Julie London.

“Julie Is Her Name,” a long-playing released by Liberty, started off with “Cry Me A River,” a tune which had been written by a high-school friend of Julie’s named Arthur Hamilton. When the disc jockeys got the record, a new hit and a new singer was born. “Cry Me A River” was also released as a single, and more than 800,000 copies of that first album have since been sold.

“The first time I heard it being played,” Julie recalls now, “I was walking down Vine Street and was all wrapped up in my own thoughts when suddenly I heard my own voice coming out at me from a loud speaker intoning, “So cry me a river. Cry me a river. I cried a river over you.”

Suddenly I wasn’t just a woman whose marriage had gone to pieces. It was me. I don’t know how to explain it, but for the first time I felt conscious of myself as a person, a woman with hopes and thoughts and feelings whom other people could like or dislike—but they’d be doing so because I was me, and not because I was once Mrs. Jack Webb.

Julie stayed there and listened. Then she went into the record shop and bought the record. She was wearing a tweed suit and a sweater and looked far different from the siren on the album cover, but the clerk recognized her. “Aren’t you Julie London?” he asked. She smiled and said, “Yes,”

“I felt as though somebody had given me something on a silver platter,” she says now. “Maybe I can’t explain it to you, but I felt, ‘I’m glad I’m me. I’m glad I’m alive. I’m glad I’m here,’ this minute, right now. For the first time, I felt conscious of my own identity.”

“The feeling was too good to lose, so I walked around the block a couple of times with the record under my arm, and then I stopped in for an ice cream soda. Then I got in the car and drove home.”

She made other records then, “Lonely Girl” and “All about the Blues,” and appearances on TV. She guested with Ed Sullivan, Perry Como and a number of other shows and did a number of dramatic roles on TV. Rosemary Clooney saw her and suggested her to José Ferrer for a small role in “The Great Man.”

The evening before her audition, Bobby Troup stopped by to see her and found her in tears. “Honey, I can’t do it,” she blurted. “I feel so shaky and sick. I can’t do that audition tomorrow.” He put his arm around her shoulder. “They want you for this part,” he said quietly. And they did, after they heard her read the next day.

The response of the movie critics, the public and the executives to “The Great Man” was heart-warming. They liked her. She was a hit!

More TV followed, and then M-G-M cast her to co-star with Robert Taylor and John Cassavetes in “Saddle the Wind.” So pleased were they with her performance that they signed her up for two more pictures, and she went over to U-I for “How Lonely the Night,” in which she co-stars with Richard Egan.

Even now, with movies, TV and records bidding for her services, Julie finds it hard to believe that she’s a success. “I still have to prove myself,” she says firmly, and you know that she means it. The doubts and self-distrust that have plagued her ever since Bobby Troup first heard her sing at a party at her home is still there, but the big difference is that now she can cope with them and conquer them.

“Sure I still have doubts about my ability,” she says candidly. “But I must admit that I’m much better than I was a few years ago. “For example, live TV petrifies me. A few years ago I was scared I wouldn’t do it. I guess that’s the big difference. The fear is still inside me, but at least now I try.

“The first day on my new picture was awful. It was like I’d never made a movie before. I had butterflies in my stomach and I didn’t think I could go through with it. But then I remembered that I’d made two other pictures before, and that people had liked them—and it got easier.”

“I don’t think I’ll ever get to the point where I’m completely satisfied with everything I do.” She shrugs her shoulders and smiles. “But at least I’m going to try to get there.” Julie London is a girl who has had to stretch and reach to find some measure of inner peace and security. She hasn’t yet achieved the belief in herself and those around her that she seeks, but she’s on her way.

Today, she lives in a large, comfortable house that’s furnished in early American and provides the home for her two daughters, her collection of antique silver and two dachshunds who are affectionately named José and Rosemary (after guess whom?). Her first royalty check from “Cry Me A River” went for a mink coat, and the others went for beautiful clothes for herself and her two children. And when she gets home to her daughters Stacy and Lisa, she’s too busy or tired to give much thought to the fact that she’s raising her children alone.

She and Bobby Troup are still a twosome, but it’s a twosome marked by quarrels and separations. Marriage? “I don’t know,” she says honestly. The scars of a marriage that failed have left their marks on Julie. She’s frightened and defensive, but perhaps Bobby Troup, who helped her learn that self-expression and accomplishment are neither to be feared nor avoided can teach her that marriage can be a good thing, too.

For the girl who thought her life was over when she was 26 has discovered the joy of living. Today, at 31, Julie London is a woman reborn.

THE END

—BY BLANCHE E. SCHIFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957

No Comments