Her Happiness Is Showing

It was the yeah 1933, a bad year all over America, but particularly bad in Chicago. The bitter winter wind blew in, over the teeming city, from Lake Michigan, driving the soot in through the windows of a small mid-city flat.

There wasn’t too much to eat in the kitchen of the flat. And not in the man’s wallet nor in the woman’s purse was there money that went beyond the next month’s rent and meager meals for another couple of weeks. And as for prospects, neither Henry Gerber, musician, nor his wife, Pauline Fisher, ballroom dancer, had any at all.

AUDIO BOOK

On this particular February day, nevertheless, Pauline Fisher Gerber was positively jumping up and down with joy. “Look at the baby,” she cried.“Look at her. She’s keeping time with her bottle to the radio music.”

Henry Gerber, a good man but serious, grunted. “This makes her a most unusual baby, I suppose.”

“Of course! Did you ever before hear of a baby with a sense of rhythm at the age of five months?”

“Beethoven and Mozart—they were composing symphonies at the age of four.”

‘Mitzi will be doing something great by the time she is four, too.”

Henry Gerber got up heavily. A Hungarian by birth, an artist by instinct, he was given to moods. He loved his gay, pretty wife. He loved his child, too. And he loved America and music, serious music. But to believe, as Pauline did, that in a national depression everything was bound to be fine; to look at a contented baby waving her bottle and believe this labeled her a genius—all of this was too much for Henry Gerber. And he had to escape it, even if it meant going out into the wintry streets, tramping about with hope of picking up a bit of musical conducting or anything else that was sensible. Alas for male logic!

Today in Hollywood that baby girl has grown into one of the brightest stars rising on the movie horizon—Mitzi Gaynor, the girl who really has never known one moment that wasn’t happy. And her mother’s adoring love has never had one setback. Even when she and Henry Gerber separated in fact, as they long before had separated in all interests, there was no harshness on either side. Mitzi recalls her father with tenderness. And Mrs. Gerber, now retitled Gaynor, too, also remembers him with admiration and affection. But the human heart, when it attains its full measure of love, definitely concentrates. Right on, from September 4th, 1932, until June 22nd, 1947, Mitzi and her mother were a closed corporation.

Mitzi and her mother and Mitzi’s career—that was all there was until June, 1947. Then it became Mitzi and her mother and Mitzi’s career and Richard Brown Coyle. Which is another chapter.

Mitzi really did wave her bottle to the rhythm of records at the age of five months, her mother insists. She also danced before she could walk. That is to say, lying in her crib, she waved her feet and legs about to the beat of whatever music there was playing. And Mamma saw to it that music played almost constantly. Other baby girls might walk at eighteen months, but Mitzi waltzed. Other little girls at three years old might be cute, but Mitzi was adorable, doing the polka and gavotte, and making deep curtseys. Other little girls, at four, might just possibly be precocious enough to think ahead about kindergarten, but Mitzi was learning the basic ballet positions from her aunt, a ballet teacher.

The Gerbers moved, about that time, from Chicago to Detroit, hoping things might be a bit better for Henry there. Actually they were. The depression was nearing its end. But Mitzi and her mother were barely aware of this new environment. Their thoughts were concentrated on Aunt Francine, teaching Mitzi the steps of “The Sleeping Beauty” suite of Tchai-kowsky. Mitzi didn’t yet have a ballet practice bar. She hung on to the bedpost instead—but she loved every moment she was dancing.

Dancing, music and love were eternally around Mitzi. And she gave the love back, unstintedly. She remembers the cherry tree, growing in the yard behind their Detroit house. She was a natural tomboy and she started picking up the green leaves as they fell to make bouquets for her mother. Then she learned to climb and pick the blossoms and eventually the cherries, all of them as gifts to Mamma.

School was okay by her, when she was older. Because good marks in school meant that she could go to the show on Saturday, she studied industriously. But she knew this wasn’t the main event. This was not what she wanted from life or even the preparation for life.

There was the wonderful week when the Ballet Russe came to Detroit. She went to the theatre every evening and she went to the two matinees. She and Mamma, and sometimes Aunt Francine, cried together at the loveliness of Markova. And Mitzi walked home, carrying her head as Markova did, holding her shoulders with that same beauty. There was a perfume at this time called “Ballerina.” The Gerbers couldn’t afford it. But Mitzi absolutely had to have some of it—and did—a whole dollar’s worth.

Her Markova personality lasted till the weekend when she saw a Claudette Colbert movie. She came home, cut her hair in bangs like Claudette’s and used the Colbert voice for weeks. Then she caught Sonja Henie and she was off again. Mamma had to make her copies of Sonja’s little skating caps and mittens and she twirled and twisted on imaginary skates.

The Saturday she saw “Wuthering Heights” she returned home, sobbing and crying. She didn’t know why, only that there was something terrifying about love. She made up her mind she’d never go in for it, that she’d give her whole life to her dancing. Boys sort of annoyed her, anyway.

They hung around her, you see. So did other girls, sensing her leadership. She was aware of this. In fact, she exploited it. The boys had a baseball team and actually invited her to join it. She condescended to do so, on the terms that they let her be captain. She loved the feeling of the bat in her hands, and, after games, she spread terror among the girls, going about, swinging that stick freely. She had no intention even of giving any girl a tap, but she loved the drama of scaring them half to death. As for any boys who tried to cut in on her, she swung at them, too. And, once when a boy tried to get her to knuckle under, she dropped the bat and beat him up angrily with her fists.

Then she got scarlet fever. That was heavenly. They sent her to Detroit’s Herman Keefer Hospital for twenty-one days and during each one of them she had a ball. She had a temperature, too, but she adored even that. When they asked her her name and address, she gave it, adding, “I am a dancer.” She was all of eight at this time. She loved the food, loved the nurses, went out of her mind with joy at the idea that she could have all the ice cream she wanted.

And she got away with murder. She told one of her nurses, “Good heaven, I need a manicure.” So the amused nurse gave it to her. One terrific intern brought her some “Miss Deb” toilet water, which she promptly splashed all over him. Another medical dreamboat brought her hand lotion, so she kissed his hands in gratitude. It was no time at all before she had the entire contagious ward—doctors, nurses and patients—doing boogie woogie. And by the time she was released, she had learned the Latin names of the less familiar diseases. She still uses these Latin terms as swear words, scaring the wits out of the less medically educated.

She grew beyond what Aunt Francine could teach her, got a new teacher, and felt she was ready for her debut. She was nine. Every day she worked at the bar, strengthened her toes, strengthened her leg muscles. She felt she could have done her dances in her sleep. And then the big night came—she was to perform for an audience.

Only, at the eleventh hour, her usual accompanist became ill and a substitute was rushed over. Mitzi, not knowing the meaning of stage fright, never gave it a thought. One quick rehearsal went smoothly between them. But the new pianist, before an audience, went to bits. Mitzi’s introductory number, supposed to be in 4-4 time, suddenly sounded out in waltz rhythm as she whirled out from the wings.

Right then did Mitzi prove she was the stuff of stardom. Because she instantly became her own choreographer, changed her steps, changed the design of her dance to fit a beat to which it had never been accustomed. She got triumphantly through the evening, with only her mother knowing the strain she had been under.

It was inevitable, of course, that she and Mamma had their bright eyes fixed on Hollywood. But they had to wait until Mitzi was eleven before they could make it. And, like hundreds before them and hundreds yet to come after them, they immediately encountered the difference between smart commercial professionalism and dreamy-eyed amateurism.

“I was to find out, in Hollywood,” Mitzi tells you today, “that at eleven, I was too old to be a child, too young to be a teenager.” But while she had to wait a whole year before she got her chance to give a professional recital in the Redlands (California) Bowl for the huge wage of four dollars, she found something very satisfying the while—a real professional children’s school. It was run by Mala Powers’ mother and every kid in it was just as ambitious as Mitzi. “This spurred her sense of competition so,” her mother tells you, laughing, “that she learned as much there in a half-day as she had learned in a public school in a week.”

The bond between mother and daughter was as strong as ever. Mrs. Gerber took a series of jobs, anything to be with her child, anything to earn the price of those ballet lessons, those costumes, those shoes. They were dedicated people, both of them, serenely dedicated to the great career they knew Mitzi was bound to have.

Mitzi shot up, outgrew her clothes, out-grew her teachers, knew happiness when she finally found a ballet mistress called Madame Etienne. Madame Etienne was no less exacting with Mitzi, but she was the first teacher to let her express her natural sense of comedy in her dancing. Mitzi was still assuming all the characteristics of every movie star who captured her fancy. Once, in a sidewalk interview, she had been caught by a strolling photographer in a shot with Herbert Marshall. She bought all the newspapers for weeks, nearly died of disappointment when the picture was never published. Another time, in a department store, she bumped into Lena Horne. She went home, raving with happiness, bought all of Lena’s records.

But now, at least, she had some humor about these borrowed “characteristics” she gave herself. When Madame Etienne came into her life—or vice versa—she was being Carmen Miranda—but for laughs. Madame Etienne let her express this—and Mitzi adored her. This was her real life, the threshold of her real career.

Her unreal life (at least to her) had now advanced to Junior High. And there, at last, she discovered boys were something other than nuisances. She found they were wonderful—probably the most wonderful things on earth. Or at least one was, the boy who had been voted “best all around athlete of the school.”

It was heaven and hell while it lasted. “Gosh, he was yummy,” Mitzi says, recalling it. He drove a “hot rod” car. On his birthday his mother gave a party for him, and Mitzi was invited as his special girl. But this was wartime and the next thing she knew he had gone into the service. Another boy succeeded him in her heart, a boy who gave her his frat pin and didn’t want her to go to New York for a show. She wore his pin East. She swore she would never forget him. She has the pin to this day. But golly, life in New York was so complex—so exciting!

In the big city, Mitzi and her mother stayed at the Hotel Edison. On account of the shortage of rooms, nobody was allowed to stay in any hotel more than five days at a time then. They said. But there was Mitzi bouncing around the place and the hotel clerk thought she was so wonderful that every five days he’d move her name off the list at night and put it up at the top in the morning. Inside their room, which looked out on a hotel court, Mitzi and Mamma didn’t dare raise the blinds for fear people would realize they had been there two weeks.

To get the sequence on her career right, it had happened during the summer of her fourteenth year that she danced a comedy bit in the Los Angeles Light Opera production of “Roberta.” She was wonderful, so much so that they promptly resigned her for the next production of the same management, “The Fortune Teller,” a few weeks later. This led to her being signed for the role of Miss Anders in the fabulous “Song of Norway” which had actually started in Los Angeles, but had, when Mitzi caught up with it, been playing three years on Broadway and was now headed for the road.

How sure she was of herself then—how magnificently, horribly sure! After all, she had put in more than a thousand hours of USO entertaining. This experience, plus two Los Angeles shows, plus her whole life of study left her, in her own mind at least, without much to learn when she went into “Song of Norway.” Remember, please, that she was only fifteen.

She found out. She came into a company of professionals who had been working together for better than three years. They beat her ears in. They upstaged her in her few little scenes. They walked in on her song cues. They killed her laughs.

“That was really the luckiest break of my life,” she says. “If that hadn’t come to me at that time, I probably would have developed into a conceited monster. But those real troupers shrunk my head back to its normal size, showed me how little I knew, how much I had to study and that should I live to be ninety there still would be things I would have to master about show business. I had it all coming to me—and I’m forever grateful that it did.”

But something else came to her by the next summer—the most important thing that ever comes to any one. Love. She was sixteen, and as one critic said, “the freshest, most blooming, talented sixteen ever seen.”

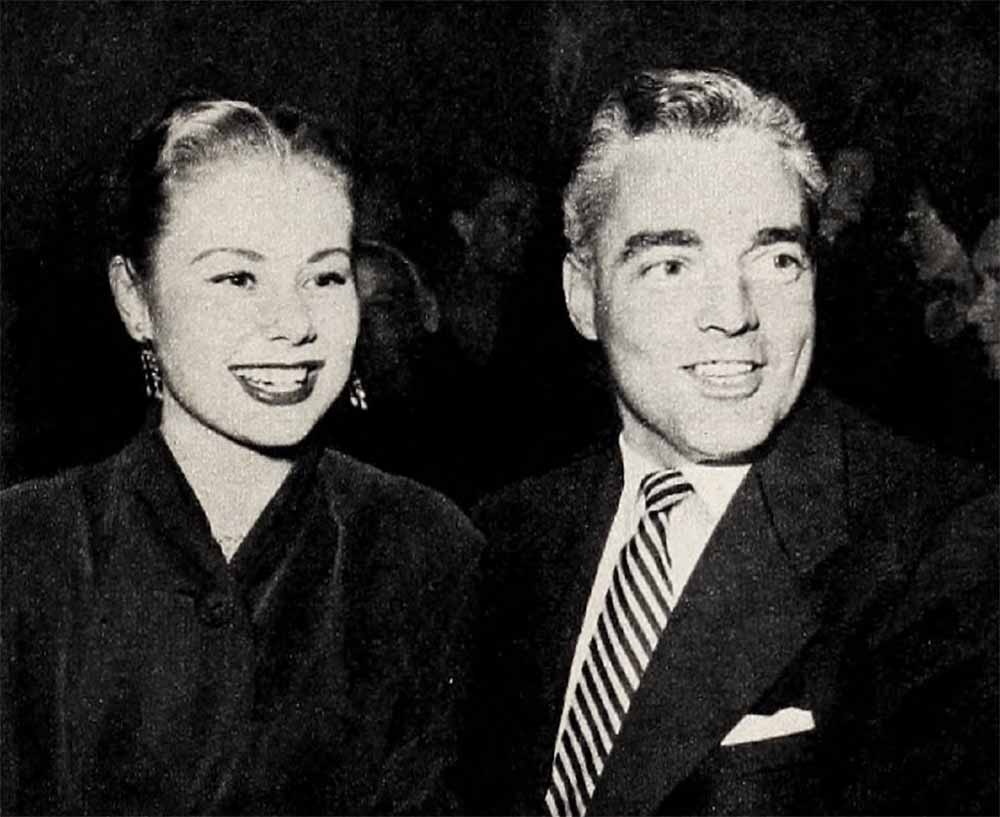

Richard Brown Coyle entered her life, even though he didn’t know it when it happened. Richard Coyle, a distinguished Los Angeles attorney, prematurely gray, merely thought he had gone backstage at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium, to visit his friend, Edward Everett Horton, who was starring in “Naughty Marietta.” “Naughty Marietta” also featured Mitzi Gerber.

It wasn’t love at first sight, not on Richard’s part, at least. He didn’t even see Mitzi. But she saw him and fell like crazy. To make sure that she would meet him, she bumped into him with a box of candy, said, “Will you have some?” After that, Eddie had to introduce her.

As a reader of Photoplay you probably know the rest of that anecdote: how, unless something very unexpected and unforeseen comes up, Mitzi will marry Richard (as she always calls him) this September when she is twenty-one. This waiting period is her mother’s advice. Mrs. Gaynor admires Coyle very much, is so attached to him, in fact, that her best friend is his mother. But she felt, and still feels, that Mitzi needed to grow up to being a wife, to gain a little more maturity before she took on the sweet and lovely demands of matrimony.

Mrs. Gaynor said to me, speaking of Mitzi and her future son-in-law, “I’m delighted with him. I’ve always known that a girl with such a love of life as Mitzi would fall in love very young. I want her to marry young, too. And I hope her marriage will last all her life. I believe it will with Richard.”

They met in June of ’47, Mitzi and Richard. They became officially engaged on the Fourth of July that year. “Reverse angle on independence,” Mitzi says, laughing.

Everything about her Hollywood career has been just as happy as the rest of her life. A dozen people “discovered” her for George Jessel, hunting a “Golden Girl,” four years before that picture was made. One test and Mitzi had a contract. She made her screen debut in “My Blue Heaven” in 1950 and bowled over the critics.

In 1951 Mitzi made three pictures: “Take Care of My Little Girl,” “Down Among the Sheltering Palms” and “Golden Girl” and bowled over Photoplay readers so that she was chosen as tops among the new stars. It was Twentieth Century-Fox who changed her name to Gaynor.

She lives with her mother on a hilltop house where everything is designed for her comfort, her dancing, her sleeping, her career—and she’s not in the least spoiled by it. She loves Hollywood, every star she’s met, every place she’s been, every picture she’s been in—and Richard Coyle most of all.

Fun, isn’t it, to know anyone can be that happy, just living, and making other people happy, too!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1952

AUDIO BOOK