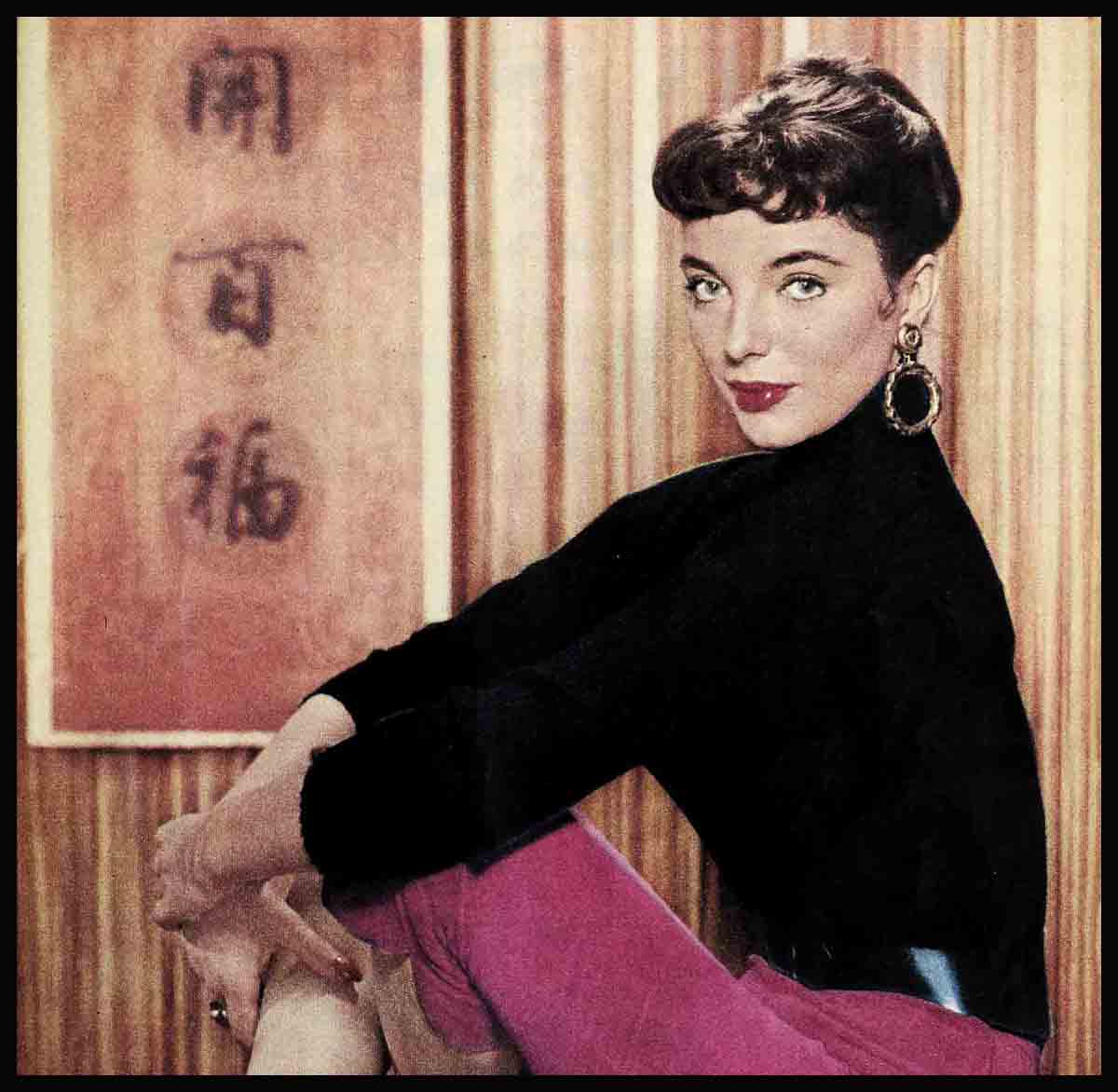

Cool, Crazy and Jolly Exciting—Joan Collins

Joan Collins, 20th’s newest British importation who seems destined to quicken pulses from eighteen to eighty, thinks America is “real crazy.” Mixing bop talk, somewhat bewilderingly, with clipped British phrasing, she seems quite unaware that she may be the heat-wave that will shake Marilyn Monroe to the very tips of her pink toes. Dressed in matador pants, which she loves to wear—they look as though they had been put on with a spray-gun—she could fill in for any of Mickey Spillane’s sultrier heroines, with her smoky gray-green eyes, small triangular face, donkey bangs, shoulder-length brunette hair and steep curves. In time, one discovers a candor that is completely disarming. This girl has no postures. Her convictions come from an utterly honest mind, are sincere as a child’s. She is incapable of pretense.

A few days ago, for instance, she came into the 20th press office, saw a pile of about-to-be-released press items and began rifling through them. “She didn’t realize the obviousness of her action,” he said, “and when she found a story about herself, she yelped like a delighted kid. That was what she was looking for and she went about it in the most direct manner possible.”

Married at nineteen to Maxwell Reed, a British actor much older than she, it required only a month or so to convince her that she had made a mistake. A separation followed, and she now plans to return to England as soon as possible for her divorce. Asked if she had learned anything from marriage, she answered instantly: “Yes, not to do it again.”

And then with young and quite charming inconsistency, she will talk enthusiastically about Sydney Chaplin, actor-son of another famous performer of that name. “Not dates,” she said, about the friendship made while acting in “Land of the Pharaohs” together, “just a date—with Sydney. He’s wonderful, handsome, talented, the very best in every way.” She thought a minute and then added: “Real cool.”

“Marriage?” she exclaimed a moment later, “how can I talk about that? I’m not even divorced. It makes me feel awfully old, too. I say, do you think I should stop telling people my age?”

She has just turned twenty-two.

Beneath her bop talk and free-wheeling unconventionality, one quickly discovers an English propriety. While in Rome, making the interior shots for “Land of the Pharaohs,” an enterprising publicity man in a moment of expansive enthusiasm tagged her with the name, “The Kiss Girl.” “It was shocking, really,” she said. “Complete strangers would ask me for a kiss. I had to be quite sharp with some of them.”

Reaching adolescence in London during the period of England’s austerity, and not accustomed to having much money in her purse, Joan reached New York in a kind of mental whirlwind after she was loaned out by J. Arthur Rank to Warner Brothers. She couldn’t get used to the idea of having money to spend on frivolities if she wanted to.

It was then that she discovered what she calls “the slot machines.” “They were simply unbelievable,” she exclaimed. “Drop in a quarter and zip! Out comes a package of cigarettes. Put in a dime, push a thingumbob, and you get enough candy to make you sick. Why, there’s actually a place in New York where a few dimes and quarters dropped into the right slots will get you a full meal. I was never so delighted with anything in my life. Couldn’t get past the machines, literally. So I landed at the Los Angeles International Airport without a cent. Had to borrow fifty dollars from a nice studio chap who met me.”

After her first ride through Los Angeles traffic, she was asked by newsmen how she liked it. “Cool, crazy and jolly good,” she said.

Any naivete, however, which Joan exhibits when talking about life in America, disappears the moment she goes before the camera. At once she becomes a trained, coolly efficient performer who knows precisely what she is doing and why. Currently she is making “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,” which is the cinema ver- sion of the life of Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, that beautiful and tragic central figure in one of the nation’s most sensational murder trials. It is a difficult role, demanding the best that any mature actress could give, and veterans of the stage and screen are amazed at the sure interpretation she brings to her part. Directors, accustomed to temperament tantrums, have had to refurbish some of their early illusions as a result of working with Joan. She is as pliable as a reed in the wind, they say. How long this will last, they add hastily, no one can say. If she ever becomes fully aware that she’s a living bonfire, only the Good Lord knows what will happen—and what we will do then.

Problematic as that may be, the Joan of today is as unself-conscious as a kitten on sun-warmed bricks. She declines to believe that people have ulterior or sinister motives. And even if they have, she says, they can be talked out of them. “People are almost always wonderful,” she says, “if you will give them a chance.” She bolsters this statement by an incident which occurred soon after she landed in Los Angeles.

Having learned to economize after she went broke in New York, Joan found rooms in a transient residential hotel. The establishment, not in Los Angeles, had no restaurant, and one night, being hungry, Joan set out in search of food. “I walked and walked,” she said, “but all I saw were houses, not a single place where food was sold, not even a delicatessen.

“Starting back I suddenly heard steps behind me. I glanced over my shoulder and saw a man wearing a leather jacket and a hat pulled down over his eyes following me. I walked fast and he walked faster. So I slowed down and all at once he was there beside me. He took hold of my arm and said, ‘Hello, baby. Out for a little stroll?’

“I wrenched my arm free. ‘Look here,’ I aid very severely. ‘What do you want?’

“He laughed, and it wasn’t a very pleasant laugh. ‘How about taking a walk with me?’ he said.

“I began talking then. I told him, of course, he was a gentleman and would understand that while I knew walking with him would be nice, it would be impossible because I must get home at once.

“He stopped dead still and stared at me, shook his head and said, ‘All right, kid. Good night.’ ”

She added then with complete sincerity, “You know, I think he may have been nice. He tipped his hat to me and walked away.”

Well, the poor bloke was licked. In the face of such simplicity, what else could he do?

Despite her present bemusement with Sydney Chaplin, Joan insists that she is far from ready to settle down. During the past year she has lived in a suitcase and this seems to satisfy her. She has visited every country in Europe, but of all the lands she has seen, England is still home. She says, however, that she would not like to remain there indefinitely. “America is wonderful,” she said. “The people are so friendly. Why, they call you ‘honey’ or ‘sweetie’ five minutes after you’ve met them. In England, following a few years of close acquaintance, someone might unbend and call you ‘duck’ or ‘duckie.’ When that happens the drawbridge to the castle is down and you’re in.”

The bop talk, which occasionally springs up in her naturally precise and conservative speech, has definitely caught on in England, she said. So have jeans, casual manners and the friendlier, less constrained relations between the sexes. This she believes is true, to a certain extent, of all European countries except Spain. That, she thinks, is a hard country to be young in. There, if a girl were to appear on the street in slacks, she’d find herself the object of shocked and disdainful glances. America may have altered the mores of most of the free world, but it hasn’t touched Spain. The old cathedrals, the hardship-graven faces of the people are even more striking after one has visited America where there are more jobs, greater freedom for the individual, bustling cities.

One of the aspects of America that bewilders this ingenuous young lady from the tight little island is the frenetic longing of almost everybody to get something “big” done in a hurry. Unless one has struggled mightily here and suffered, one hasn’t really lived. In England, she says, people are more likely to shrug their shoulders at that will-o’-the-wisp called success. Struggle there, she says, is definitely frowned upon, especially at teatime.

She herself has never struggled, she said, obviously holding the opinion that too much emphasis on such things is not only unpleasant but very bad taste. She will admit, under pressure, that she worked hard at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art getting a solid background for her career, but there was no “gruesome sweating it out.” Asked how she happened to come to America, she said: “Well, I met Howard Hawks one day in Paris. Six months later he called me on the phone and offered me the lead in ‘Land of the Pharaohs.’ It was as simple as that. He gave me three days to make up my mind, but he needn’t have. That was done before he’d stopped talking.

It was “Land of the Pharaohs” which led to her being signed to a long-term contract at 20th, and she considers this the most fortunate event that ever happened to her. At once she plunged into America up to her neck, bought a Ford convertible and began thrilling to the asphalt mating call, commonly known as the wolf whistle. Coming from young men she thinks these are “cute” but revolting when the whistler is old enough to be her father.

Her first picture at 20th is “The Virgin Queen,” a story about the life of Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh. For this role, she was compelled to learn sidesaddle riding, a feat she considers only slightly less hazardous than going over Niagara in a barrel. “The horse they gave me to learn on was Old Jim,” she said. “This monster, masquerading behind a long, sleepy-looking face, was actually a murderer at heart. I knew it the moment I looked at him. He just missed killing Anne Francis, though everybody made excuses for him. ‘Poor old Jim,’ they said, ‘he just went to sleep when Anne was riding him, got his feet crossed and fell on his nose.’ But I knew better. It was deliberately planned.

“The first time we met he started sneering at me, curling back his upper lip over his nasty yellow teeth. Every time I rode him, wearing that long trailing habit that goes with sidesaddles, I could just see the wheels turning in his mean old head. He was figuring out ways to do me in.

“Finally we got everything set. I was to ride Old Jim down a steep mountain trail. As soon as he saw it, he knew this was his chance. I could tell the way he closed his eyes as if he was having a hard time staying awake and was bored with the whole business.

“It took the combined efforts of every member of the crew to get me up on that animal and point him toward the path. I knew they’d remember this afterward as The Kid’s Last Ride, so when the director called, “Action” I gave Old Jim a sharp dig with my heel and before he knew it we were flying down that terrible path in a cloud of dust. I don’t know to this day how we got to the bottom, but we did and, when it was over and everybody was talking about my beautiful, thrilling ride, Old Jim turned around and stared at me. If ever I saw loathing on an animal’s face, I did then. He’d missed his chance, you see, because we were going so fast coming down that if he’d tried to kill me he’d have finished himself off, too. We haven’t met since.”

Born in London on May 23, 1933, Joan grew up in the atmosphere of the theatre. Her father, Will Collins, is a prosperous vaudeville booking agent who was dead-set against his pretty daughter having anything to do with the rugged life of the variety performer. Hating school and skipping it whenever possible, Joan kept importuning him for a chance to go on the stage which was much more alluring to her than the prosaic routine of dull classrooms. Collins’ views, however, were shared by Joan’s aunts and uncles, some of whom were performers in the theatres Will booked. They drew unflattering pictures of stage life behind the outer glamour which the public sees, and tried to discourage her by every means possible.

At this juncture of Joan’s life World War II was absorbing England and she was being shifted from one evacuation area to another. The roster of schools which she attended reads like a catalogue of British educational institutions.

But no war lasts forever and, when this one ended, Joan returned to London to dutifully, but with great reluctance, finish high school. The ink was hardly dry on her diploma, however, when the memory of her early ambition flooded back into her mind with redoubled force. Slipping the leash of paternal authority, she entered the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

“None of the family had ever acted in what we call legitimate theatre,” she said, “and I finally persuaded Daddy to agree with me—or pretend that he did—in my contention that dramatic acting is as honored a profession as, say, law or medicine.

While completing her course at the Academy, Joan did photographic modeling. It was this avocation which won for her the first movie opportunity. “They were looking for a girl to play the lead in ‘Lady Godiva Rides Again,” she said, “and the agency submitted my picture. I tested for the part and won runner-up place which gave me a bit role. So, you see, no heartaches—just fun.”

From this picture she progressed to others and soon was spotted by J. Arthur Rank, the great English producer. She made only one film under his aegis, however, having been loaned out again and again to other studios. It was the last of these, to Warner Brothers for the picture, “Land of the Pharaohs,” that led to the purchase of her contract by Darryl F. Zanuck or 20th.

“I can’t see a thing that will stop the Collins girl,” a studio executive said. “She’s exciting to look at; she can act like a house afire and she knows where she’s going.”

One day in the commissary an elderly, distinguished gentleman approached her table. This was Spyros Skouras, president of 20th and one of the truly great men in the motion-picture industry. He patted Joan’s shoulder and inquired with fatherly affection if she were all right, if she were quite happy.

Her replies and her manner with this imposing personage were interesting. No slang crept into her speech. She was neither obsequious nor too casual. She was poised, respectful, yet not in the least flustered.

When Mr. Skouras left presently, she followed him with admiring eyes. Then she said thoughtfully: “There does seem to be some point in struggling after all.”

Yes, it appears likely that Miss Collins will go a long, long way in her chosen career.

THE END

—BY HYATT DOWNING

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1955

No Comments