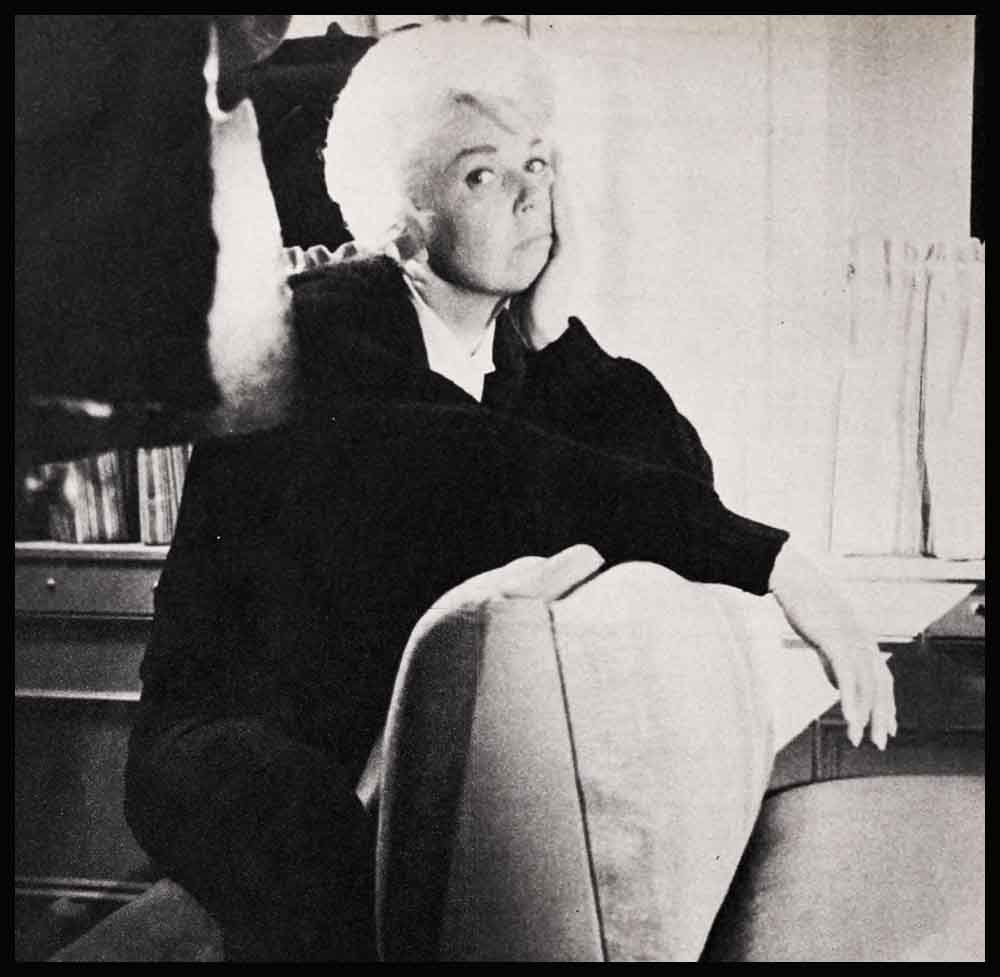

Is Doris Day Sick Of Being A Good Wife?

“I’m a difficult character to live with,” Doris Day admits.“Marty should know, he’s been living with me for nine years. I run his home—but I’m too darn clean. I cook for him, but not so good as my mother. I’m bossy, I criticize him—is that the kind of a wife aman really wants?”

Doris grins fondly at her husband and adds, “But Marty isn’t so perfect either. Do you know what this man does to me? He falls asleep right while I’m talking to him! We’ll be sitting in the backyard soaking up sun, because I’m between pictures and I can relax. . . .”

“She means that’s when she can take a chance on getting more freckles,” Marty Melcher teases. “When she’s working they show up too much. She loves to poke her face in the sun, and for some reason it makes her feel talkative. But it makes me very sleepy—the sun, I mean. . . .”

“. . . so the next thing I know, I’m talking to the wall!” Doris breaks in. “Just talking to the blank wall and a fast-asleep man! It makes me so mad I get out of my chair and march back to the house. . . .”

“Dragging me with you, don’t forget!”

“Okay.” Again the broad grin. “I said I was bossy, didn’t I?”

AUDIO BOOK

Marty puts it this way. “Doris and I have a talent for staying close, for two excellent reasons. One, I like it. Two, she insists on it.”

But then he adds, “Seriously, I do believe in closeness—it’s the heart of any marriage. I feel very close to my wife, and her mother, and Terry.”

“He only married me to get my mother and my son,” Doris insists. “He tells everybody, ‘I certainly married a beautiful package deal.’ ”

“And so I did,” Marty agrees heartily. “My wife’s relatives are my friends, not my in-laws. I have no use for the in-law relationship, I don’t even like the expression. We’re friends because they’re nice people to have around—it’s only a coincidence that they happen to be your relatives too.”

In answer, Doris bounds across the room to throw her arms around her husband and kiss him with an enthusiasm that all but knocks him down. Marty does not call his mother-in-law by title—sometimes it’s Alma and sometimes Nanna—but Doris enjoys the way they get along. Alma-Nanna lives with them and runs the household. And about this Doris has another confession.

“Don’t tell Marty,” she whispers, “but I hate to cook. And my mother is such a whiz that when he puts on weight he complains to her, ‘Oh you cook so good you make me mad.’ So you see what a good wife I am? Do I put pounds on him? No, it’s my mother. And Marty jokingly announces to Nanna: ‘Nanna, I hereby give notice that if this wife of mine ever acts up, I’m going to be the one to get custody of you. You’re never going to get away from me.’ ” Doris deliberately turns down the corners of her mouth in a sad droop. “Honestly, they gang up on me. Around here I’m a nobody—I have no say at all. I’m the one who always loses—and I’m a bad loser.”

Marty goodnaturedly points out that one minute she admits that she’s bossy and the very next minute hollers that she has no say.

“Who,” he demands, “looks me over like an inspector general before we go anyplace?”

“Me!” Doris agrees brightly. And explains that if she didn’t, he might go to a formal party wearing a light suit. The Melchers don’t go out socially a great deal because both of them adore their home and all they want is to get back to it if they’ve been away. “I love coming home,” Marty says and Doris nods knowingly, remembering that from the time he was eighteen Marty lived in hotels too much and longed for a home. Now he has one and revels in it. That’s why they by-passed interior decorators and shopped together for furniture and fabrics they enjoy living with.

But when they do step out, Doris admits she will make Marty stand inspection, and even go back to change into a dark suit if the invitation calls for it.

“What’s more,” she boasts proudly, “I pick out his ties, and he lets me! Now he’s acting put-upon, but actually he goes around telling people ‘my wife has impeccable taste. Those are his very words. Impeccable.”

Marty does go shopping with Doris, too, for the fun of it, admiring everything she buys for herself. He can’t get over how sensibly she spends her money. “My wife looks elegant in a skirt and sweater,” he says proudly. “She doesn’t need a three hundred and fifty dollar dress to make her attractive. And she’s a lot more sensible about clothes than many a girl who never had to earn a quarter.”

“I can’t resist it’’

Marty feels that people shouldn’t spend money out of line with their income, even when it comes to the beautiful house they both love. “If you pay more for a house than you should,” he says, “it becomes a snare and a delusion, and you can’t walk into your home on a solid foot.”

“Oh I agree with you a hundred percent,” Doris nods like a wise owl. “Until,” she adds, “until it comes to something for the house that’s so beautiful I can’t resist it.”

Marty throws up his hands. “That’s why I have to act as a stabilizing influence. She’s for economizing but beauty gets her. . . .”

A strange glassy look has come into Doris’ eyes, and she hasn’t heard one word of this. Her gaze is fixed on one particular place in the rug, and she stalks it like a tiger—then pounces! A piece of lint! She picks it up in her fingers, muttering something about this place having been vacuumed less than an hour ago. . . .

And then she exclaims, “Oh isn’t that awful of me! I am too fanatic about cleanliness, I know it. I’m sure no man wants his wife to be all that clean—but I can’t help it. I can’t stand dirty ash-trays, and clothes lying around on chairs all over the place. I loathe messy kitchens! I can’t bear to eat in a strange restaurant unless I can peep into the kitchen.”

She goes back to her perch on a foot- stool near Marty’s chair and beams up into his face. “Of course,” she says, “I’m lots better about it than I used to be before Marty took me in hand. Terry would come in dirty from playing outside, and it bothered me out of all proportion. Anyway, to be perfectly honest, I didn’t always understand small boys. But Marty’s always been fine at handling my son—I should say our son. Marty legally adopted Terry, you know. He always knew what to do when Terry brought spiders home or got mixed up in fights. I’d scold, but not Marty—his voice just gets firm. And if Terry was dirty, Marty would calmly send him up to wash. And then he’d say to me, ‘Hon, a boy has to get dirty. I used to get dirty all the time. It comes off in water.’ And you know, he was right. All of a sudden dirt stopped being a problem. I’m grateful Marty taught me that.”

And two minutes later, she darts off the footstool to pick another speck of anything off the rug. Marty watches with a grin and says nothing, until Doris catches on and laughs too—at herself.

“I guess I’m a difficult character to live with,” she announces. And promptly confesses to a list of sins as long as your arm. Such as: she annoys him by reading the paper in the car while he’s driving, instead of enjoying the scenery . . . has a habit of keeping three books going at the same time, which baffles him sometimes “tunes out” of a conversation by daydreaming, and comes to, deeply apologetic . . . tells little fibs. “You even lie about the ages of your dogs,” Marty accuses. “For years now you’ve been saying that Smudge and Beany are only three and five years old apiece.”

“I can’t bear to think of them as getting old,” Doris explains. In fact, she’s sentimental over everything that has a meaning in her life, from baby pictures to frayed pillowcases. When she was still in high school, she remembers, she kept her first corsage in the refrigerator for two years.

“And I hate to eat alone,” she adds, remembering another fault, “even though I’m really not cheerful until after I’ve had breakfast.

“And we make each other jumpy,” she sums up.

“Jumpy?” Marty echoes, placid but puzzled.

“Jumpy. I’ll be having my massage and I’m so relaxed I feel marvelous. Suddenly there’s a hideous scream—a woman’s! And then a man snaps, ‘Shut up and get into that coffin, sister.’ By the time I realize it’s only the TV turned up too loud, it’s too late. How can I get relaxed again? I can’t.”

“Oh that,” Marty understands now. “That’s just to fix you for rehearsing your lines in bed while I’m trying to drop off to sleep.” He explains, “I’m peacefully dozing and she’ll suddenly shout, ‘I’m going to have you thrown in jail for this, you cad!’ It’s enough to make anyone a nervous wreck.”

“You see?” Doris sums up.

“You see?” Marty echoes.

“I know my faults’’

“I said that first! I know my faults.” She lists some more serious offenses. The telephone, for instance. She claims it’s her pet aversion, but Marty insists she’s always on it. Including his calls. Business or personal, it doesn’t matter, a bright voice comes on the extension, asking, “Who is this?” “And if it’s anyone she knows,” Marty groans, “I don’t get another word in edgewise.” . . . She criticizes her husband. Marty looks on himself as a whiz with hammer, nails and paint, but she tries to limit his fixing to the rough outdoors. “Inside we’ll have experts,” she decrees. “And what am I?” he wants to know. “A doll—but you put up some crooked fence.”

“Well,” he retorts, “you re-arrange the furniture so often I sometimes come home and wonder if I’m in the right house.”

Doris laughs and goes on with her list. Although she’s systematic and orderly in everything else, her desk is such a mess that Marty goes crazy trying to sort out bills and such. . . . She found that the game of Scrabble was making her nervous, so he had to give it up too. . . . “And I used to have a trigger temper,” says, “but I’ve learned to curb it.”

“Actually,” says Marty, “my wife and I get along very well indeed. Sometimes twenty minutes go by with never a cross word.”

“Oh Marty, don’t,” Doris wails. “People might believe it. It’s one of those twoway cracks. Like ‘When did you stop beating your wife?’ ”

“Oh, weeks ago.” And then suddenly he asks, “Listen, why don’t you tell the good things about yourself. I bet you could find a few if you tried.”

“You cad!” Doris says, laughing. “I’ll get even with you.” She picks up a pillow from the couch and starts to toss it at him. He throws up his hands to ward it off. Then, changing her mind, she kisses him lightly on the tip of his nose and lets herself get coaxed into admitting a few good points about herself.

“A square at home”

“Well, let’s see—I hardly ever get traffic tickets . . . and I’m proud of how good I iron . . . I never get seasick . . . I sleep like a rock and get up eariy . . . I don’t believe in separate vacations for married couples . . . I agree with my husband on politics . . . I don’t smoke, or drink—except milk and sodas and malts.”

“We’re both non-drinkers,” Marty says, “so we entertain by throwing daytime parties in the backyard. That way we don’t have to disappoint guests, who’d naturally expect liquor at night, and still we don’t have to violate our own beliefs.”

“That’s right,” she backs him up, “we decided to be real squares and admit right out we preferred an ice-cream bar to a liquor one. If you can’t be a square in your own house. . . .”

Suddenly, the clowning over, Marty leans forward and says seriously, “Listen, honey, you’re only telling the little things. Not the big stuff, like the way you believe in happiness.” He explains. “Doris thinks everybody should be happy, or at least try to be by thinking happy thoughts. She’s right, too. It’s one of the things I’ve learned from her and I’m grateful for it.”

Somehow, at this point, Doris has sidled over to him and is sitting nestled against him with her hand in his.

“The miracle about this girl,” he says, “is she’s never grumpy, no matter what she says about before breakfast. And believe me, that sunny disposition is no pose. Nothing can take away her joy of living for long. She’ll grieve, but not brood. But don’t think she can’t feel deeply—she’s a warmhearted girl who gives all of herself. She’s had more than her share of setbacks and heartbreak, enough to sour most people, but not Doris.”

Which goes back to when things weren’t as good as they are now. To an early automobile accident that nearly crippled her, and cut short a promising dance career, so that she had to start all over again by taking up singing. To when, a child of divorce herself, her own youthful marriage ended with a child to raise and support at an early age when life is first beginning for most girls. To when she and Marty first met. Both were separated from their respective spouses, but neither had done anything about divorce—not till they decided to marry each other. Doris got hers in June of 1950, but Marty’s didn’t come through until the following February. They were married on April 3, 1951—her twenty-seventh birthday.

“And he’s been my tower of strength ever since,” she says. “What I love most in him is his kindness. Sometimes he’ll make a pretense at being cynical, but it’s an act. Terry knew he was all right the minute he laid eyes on him—kids have an instinct. Marty’s the softest, gentlest man I’ve ever known. He’s a great father to Terry and a wonderful husband to me.”

Says Marty, “Doris is a wonderful wife for me. She has a deep, instinctive confidence in life, she knows it’s terrific and everything happens for the best. I admire her for it—and envy her.”

“When I was in love before,” she says, “I only knew it as heartache and misery—I thought that’s the way it had to be. But from this fellow,” she smiles, giving his hand a squeeze, “I learned that love takes quite a little growing-up-to—but then a marriage gets to be the most marvelous experience two people can share.”

“That’s right.” Marty’s arm goes around her in a protective gesture. “Sharing is everything.”

“I never have a secret from him,” she goes on. “I don’t think a wife ought to hold back anything that bothers her. I tell him everything—but I had to learn how. I didn’t have what he calls the ability to communicate my secret feelings.” Then, with a gamin smile, she adds, “He even knows I lighten my hair. And he likes me in the morning before makeup and a haircombing. It may not be what all the female experts say is the right way to run a marriage,” she says, making a face to show she’s sick of trying to be their idea of a good wife. “But if that’s what Marty likes in a wife—a female who doesn’t bother to keep her beauty secrets from him—brother, he’s got it.”

“Oh, I’ve got more than that,” Marty says airily. “If you really want to know the secret of our happy home, here it is: half the time I let my wife have her own way—the rest of the time I give in. So we get along fine.”

“See?” Doris chirps in triumph. “Isn’t that what I say? Pay no mind to the rules—if your husband likes you, you’re a good wife.”

THE END

DON’T MISS DORIS DAY IN “MIDNIGHT LACE” FOR U-I. SHE SINGS ON THE COLUMBIA LABEL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1960

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments