An Open Letter To Marilyn Monroe: Honey, You Can Have A Baby!

Dear Marilyn,

Remember when you said, “If I had a child, a little girl, I would bring her up to have all the things I never had. I don’t mean material things like clothes and money. They’re nice, too—but—I mean love. People caring about her. People smiling when she came in, wanting to make her happy. I’d bring her up not to be afraid. It’s not what a child can do for you—it’s what you can do for it that makes you happy. I guess I’d rather have a baby and be able to do that for her than anything else in the world.”

Do you remember those words, Marilyn? They’re your words—spoken by you almost five years ago. You weren’t even married then. You had just burst into fame by trading in your good mind and your decent soul for a sexy reputation and a lot of publicity. But even then—those were your words.

You wanted a baby.

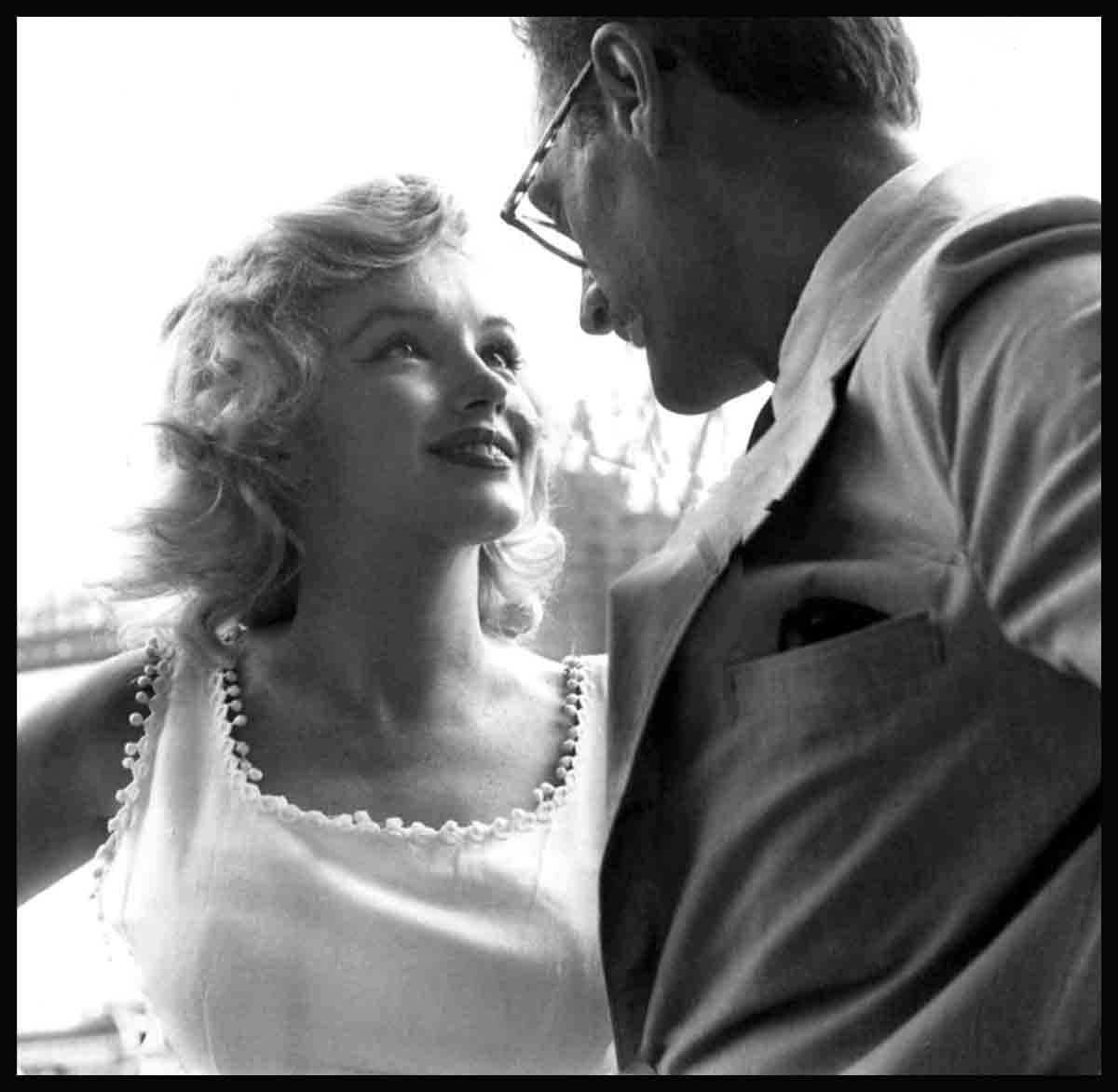

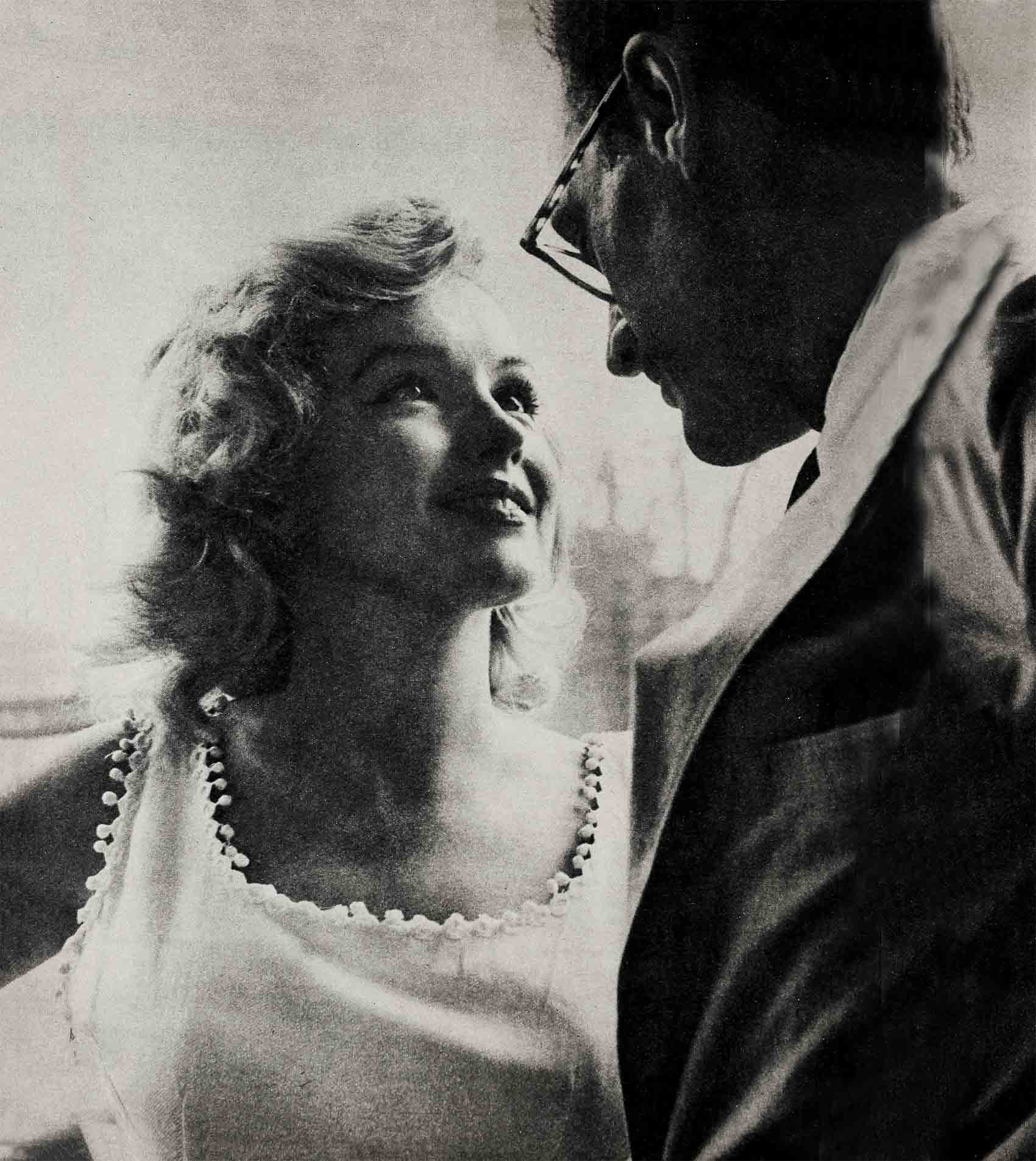

And now you are a married woman. You have a real love, a real home for the first time in your life. A home not likely to vanish in a puff of smoke, a love not endangered by a small quarrel or even a big trouble. You’ve proved that you can stand by your husband no matter what. You have a life now, to bring a child into.

And yet, there is no baby.

You have had two miscarriages, trying. We know that. The first brought an end to a pregnancy you hadn’t even admitted to. You were making The Prince And The Show Girl then, and it was your first movie on your own, the movie that was to the world that the dumb-blonde bit you’d been playing off-screen and on for so long was just an act. But it was a glamorous part, and nothing was to spoil the impression you wanted to make. So you said you weren’t pregnant, and you and Arthur and a few close friends hugged the secret in private—you were going to have a baby. There would be plenty of time to announce it when the picture was done.

But the announcement was never made. The baby was never born. All the world got was the sudden ring of truth in your sad denials: “No, I’m not pregnant. Please, leave me alone.”

That was the first time.

The second—well, the second is more than half a year behind now—yet it still Those weeks of happiness in the privacy of your first real home with Arthur. The glow when you admitted there was a baby coming. The talk, the plans, the sense of fulfillment. And then—the nightmare ride to the hospital and the knowledge that this baby, too, would never be born.

A baby so young that even the doctors could not tell you if it would have been a boy or a girl—and it, too, had to die.

Do you know, Marilyn, that we still get letters—all these months later—weeping for you and your baby? It’s true.

And sometimes they ask, “Why doesn’t Marilyn try again?”

For you said you would. We remember the pictures of you when Arthur took you home from the hospital. You smiled for the cameramen and you walked down the steps. yourself, though you shouldn’t have. You waved your hand from the window of the ambulette and you said in a loud brave voice: “I’m going to have a big family. A big family—”

Marilyn, is it true that you’ve changed your mind? We hear that it is. That you’ve been tired and weak, that your recovery had left not physical scars but a more dangerous wound—discouragement, despair. We hear now that you are afraid to try again, afraid you were never meant to have that one greatest joy—a child to love.

That’s why we’re writing to you this way. Bringing out into the open things that are usually left for the privacy of a husband and wife. We’re writing to say just one thing: you can have a baby.

We’ve done some checking, asked around. Your last pregnancy failed because somehow the baby was conceived, not in the womb where it should have been, but outside it, in the Fallopian tube. This is an accident, a mischance that does not, thank God, happen often—but often enough for the doctors to know all about it. And the doctors say that there is no reason why it should ever happen to you again.

But sometimes it goes deeper than that. Sometimes there’s another barrier that keeps a woman from bearing a child.

What is the name of that barrier? Worry? Tension? Fear? Whatever its name, June Allyson met it once. Do you remember? She and Dick wanted so to have a baby. They went to doctors, had tests made. But time went on and no baby came and finally June found herself crossing streets to avoid friends with baby buggies, or a child waiting for its mama. They were bad days for the Powells, and then they adopted Pam. They found her in an orphanage in Tennessee, where so many movie stars have adopted children, and her brown eyes smiled at them. There were papers to fill out and time to wait, but finally they carried Pam home—and that might have been the end of the story, the three of them, happily ever after. But it wasn’t the end. For the next year June—without benefit of doctors and tests, without fear, without even thinking about it, it seemed—became pregnant and gave birth to a son. Now there are four of them—June and Dick, Pam and Richy, to share the ever-after.

A natural miracle

An isolated example? No, not at all. Lita Calhoun was another one who finally became pregnant—after almost adopting a baby. There are many, many others in Hollywood. And the adoption agencies will tell you of literally thousands more—supposedly childless women, who opened their hearts to a stranger’s child, and suddenly found that they, too, were able to give birth. There have been volumes written, trying to explain why.

It seems sometimes as if there is more room for a child in a full home than in an empty house.

And then there are the others, the people like Roy Rogers and Dale, whose homes have found room not only for their own children, not only for their adopted children, but for the children whose real parents can neither care for them nor give them up altogether—the most homeless children of all: the foster children. These children move sometimes from house to house, going wherever there is room. They may live in one home for years—or in a dozen in twelve months. They write to their parents, visit them, love them—and long for them. For they are nobody’s children.

And you were one of them once.

We won’ go into that now. It’s been told so many times. The years of anguish, the loneliness, the left-out feeling, the hurt. The changing women who told you to call them ‘Mama’—and the worse ones who told you not to dare. The ‘fathers’ who accepted money for your board and room from the state—and worked you like a servant. And the scornful children who did belong—and saw to it you never forgot that you did not.

We know that’s all behind you. We know you’ve earned your love and your place in the sun, that those years are over for you now. But, Marilyn, there are other children for whom those years are just beginning. There are other girls as desperately in need of love as you were once, as homeless in every house.

Love’s gift

And all they need is what you have to offer. Not the material things. But—in your words—“Love. People caring. Smiling. And not being afraid.”

If your arms are empty now, they could so easily be filled.

And we don’t have to tell you—you know it so well—what such a love could mean to such a child.

Twice now, we’ve repeated your own words to you. Now we’d like you to read the words of another woman. She once said this:

“Show business at best is a false existence. Fame is a fleeting thing. The tinsel fades. The public may be fickle and forget you. But your child is always there to love you and open an umbrella when that proverbial rainy day comes into your life.

“A child doesn’t care if the critics pan you. Your child believes you are perfect. A child doesn’t judge you by your bank account. Your love is its riches and its love is your gold. A child doesn’t care whether you’re under contract or between jobs. A child doesn’t care if you reach forty and have to take a back seat for some other rising star. Your heart may ache, but your child rejoices that you’re home at last—where you belong.”

You know who wrote that? Not a poet or a novelist. Another ‘dumb-blonde’ as a matter of fact. Her name is Gracie Allen, Mrs. George Burns. And she was speaking of her adopted children.

Think about it for a while.

We believe that—even more than most women—you are meant to be a mother, Marilyn. We hope with all our hearts you make it soon.

With love,

David Myers

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1958