Life Begins With Marriage—Dale Robertson

One day last May, Dale Robertson braked his racy Nile-green British MG at the curb of a sports shop in Hollywood and turned to his missus seated in the car beside him.

“How’s about stoppin’ in here, Jackpot?” Dale asked.

“Why, Dale?” Jacqueline, wondering how the sitter was making out with baby Rochelle, glanced disinterestedly at the store.

In the shop, Dale’s smoky gray-green eyes under their thicket of black lashes widened with excitement. “Hiyah, Pop,” he yelled to the proprietor. “Aimin’ to find a fishin’ rod to hook a mess of trout.”

Dale studied rod after rod with deepest concentration. “Honey, how does this one look to you?” he finally asked Jackie.

He watched her flex the rod and nod with approval. “Okay, Pop, wrap it up,” Dale said. Then he turned to his wife. “That, Frederica Jacqueline Wilson Robertson, is your Mother’s Day present!” said Dale in his soft, Oklahoma drawl. “I figure to make an expert fisherwoman out of you.”

“Thank you, Dayle LyMoine Robertson,” Jackie curtsied in her politest manner.

Four out of five wives of Hollywood film stars would have stared steely-eyed into the mouth of that gift horse—then unceremoniously flung it at their ever-lovin’ spouses. But not Jacqueline.

To her it signified that two years of marriage had mellowed Dale into a true oneness with her—that he wanted to share fully with her not only his everyday life, but his hobbies as well. For Dale, a man’s man to the core, had gone on record early in their marriage with words forbidding to any bride: “When a man works six days a week, he should have the seventh off for sports—if he wants that. And one complete weekend a month to go off by himself hunting or fishing. A man’s spare time should be his own.”

On May 19, 1953, Jackie and Dale blithely celebrated the second anniversary of a storm-tossed marriage which Hollywood wisenheimers had prophesied would never survive. The Robertsons celebrated that day simply—in the pattern established a year earlier. First a fine steak dinner, and then they shopped around for a movie. As they drove by Grauman’s Chinese on Hollywood Boulevard (both are avid movie patrons) they noted that an unnamed major preview was an added attraction.

And they both burst into surprised laughter as the credits unfolded on the screen—Betty Grable and Dale Robertson in “The Farmer Takes a Wife.”

“What do you know?” said Dale.

To commemorate that precious second anniversary Jackie presented Dale with a leather foldup sports stool and a box for his fishing gear, while Dale gave Jackie a beautiful dress and matching purse to wear with the luxurious breath of spring mink stole her parents had given her as a wedding gift.

“I’d rather you’d pick out your own dress,” Dale had told her. “Even if you offered me a fine quarter horse I wouldn’t be caught alive in one of those ladies’ stores. Not since that time in New York when I bought you those maternity outfits. You’d have thought I had forgotten to wear my trousers the way those customers and salesgirls stared at me!”

Jackie remembers gratefully. There’ve been some changes made in the erstwhile jackhammer operator, bulldogger and prize fighter. The wild, unbroken Oklahoma colt had taken a little longer than most to be gentled into double harness.

If you were driving through the GI house community of Reseda in the San Fernando Valley looking for a bona fide movie star your chances of finding one would appear slim. Nevertheless, that is where the Robertsons reside, though it is some twenty-five miles from fashionable Bel Air. It’s a long way from Hollywood to Reseda in more ways than one. For Dale Robertson is not Hollywood. And this modest three-bedroom house ($200 down and $58 a month) emphasizes it. There are no fish-tail Cadillacs, no swimming pool, projection room or tennis court. But there, directly across the street, is Reseda Park (“biggest backyard any star’s home can boast”) with space for Dale’s favorite softball games and room to romp his dogs—Chief, the German shepherd, and Radar, the pointer.

And in this modest home, baby Rochelle amazingly advanced for her fourteen months, darts around the house with the agility of a wiry two-year-old.

“I’d always heard the first year of marriage with its personality adjustments was the hardest to make. But now,” Jackie sighs, “I’m told it’s the first five. Three more to go! You know, in our case, I just don’t believe it. I think all the stress and strain is behind us. Dale and I knew so little of each other and so little about marriage two years ago. Marriage is lots more than champagne toasts and dreamy waltzes. And really nobody can tell you—you’ve got to find out for yourself.”

An expert marriage counselor, studying Dale’s and Jackie’s personality traits and backgrounds, could have told them, back on their wedding day, May 19, 1951, that the going would be rough for awhile. Even without the use of a crystal ball he might have prophesied that short tearful separation and eventual reconciliation. But these two young people really love each other, and that’s why they are together.

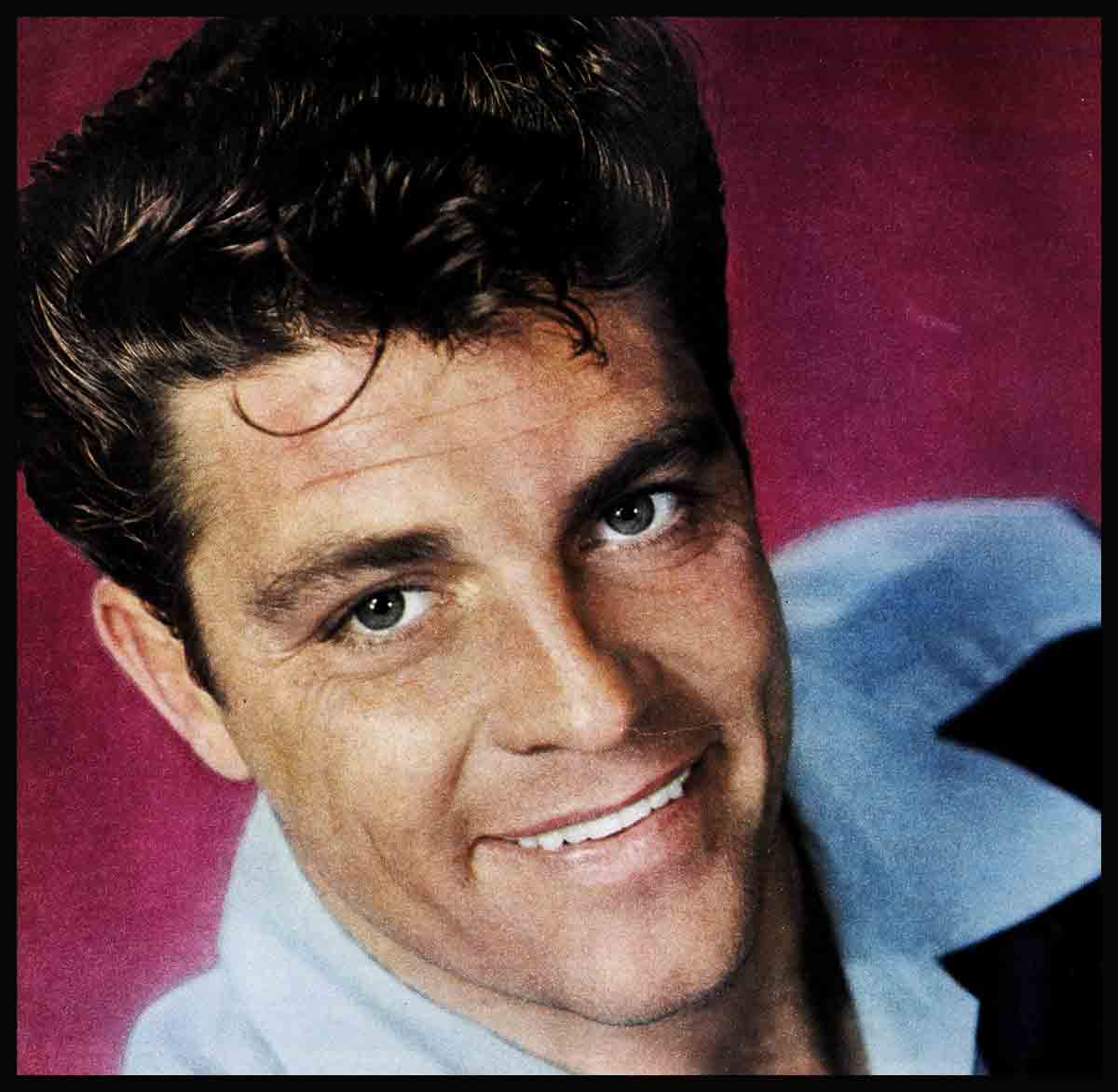

Experts know that marriage, particularly at its beginning, is a state of “antagonistic co-operation.” The sexes are different, physically and psychologically and there is likely to be conflict. In looking at Dale, the expert would arrive at some conclusions and then he’d want to study his early life. Physically, Dale has the rangy, broad- shouldered, narrow-hipped body and the chiseled, sensitive though strong features of a prize fighter—which Dale has been in his time. His gray-green, moody eyes framed in their devastatingly long curly lashes are the kind of eyes women love. The flirtatious eyes, the flashing grin, the gift of Irish blarney topped off by a rare kind of courtly southern gallantry (he still says “Ma’am” to every woman) mean that Dale has had more than his share of attention “from the fillies” ever since he pulled the pigtails of the little girl in front of him in the first grade. Even then, his chin probably showed a dominant, aggressive, outspoken personality, while his deceptively gentle Oklahoma drawl masked plenty of stubbornness and iron will.

It’s the kind of personality which frequently accompanies natural male rebellion against a mother with dominant strength of character. And that is what Dale, youngest of three sons, had in his beautiful Irish mother, who today looks like a slightly older sister instead of mother to Dale.

As he explains, “Mother had a fiery nag back there in Harrah, Oklahoma. It was a hot muggy night and Mother says she was restless at the end of her pregnancy. So she mounted Prince and took off cross country, sailin’ over fences and ditches in the moonlight. Knowing her fourth child was about to be born, she just galloped Prince right on past the house and straight up to the hospital. If that Prince hadn’t been such a fast horse I’d have been born right in the saddle.”

His father, small and wiry Melvin Robertson, was a high wire man for the electric company—a restless man, unhappy in the confines and responsibilities of marriage, and when Dale was six his parents were divorced. From then on, Mrs. Robertson, a capable, independent woman, off-spring of many generations of western pioneer stock, supported and reared the boys “and umpteen dogs” alone. In addition to her petticoat government, Dale was coddled by two maiden aunts.

The Robertsons are a clannish, close-knit and sentimental family. Not a week goes by without Dale’s phoning his mother two or three times. Even today, Dale still talks and acts as if he’d never left the sagebrush and wind-swept sand hills.

For a short while in his late teens during the war, Dale’s heart was drawn to a girl in Oklahoma about whom Hollywood has learned little. They married, lived together briefly, and parted with a quiet divorce. Explains Dale, “It was one of those things which just didn’t work out. She was a fine girl, but I’d rather not discuss it. I guess the truth is I just wasn’t ready for the responsibilities of marriage and raisin’ a family, and when things didn’t work out we decided it was better to part.”

After that there were girls aplenty—how could there help being with such a supercharged male personality as Dale’s? But there came a gala night, April 14, 1951 (“I’ll never forget that date,” says Dale), when the ex-bulldogger found himself a bit out of his element. He’d been invited to a dinner party, and the sophisticated conversation fluttered around confusingly in rapid-fire language. Dale’s gray-green eyes lost themselves, and at some length, in a pair of eyes of the identical color. They belonged, of course, to nineteen-year-old Jackie.

The youngest of three children, Jackie was much indulged by loving parents who tended to keep her young, even for her tender years. Where Dale rebelled against a strong mother, Jackie, a sensitive, proud girl, was dependent on her parents, docilely following the pattern they established, yet able, by feminine tactics, to get her own way. She is the daughter of Broadway actress and silent star, Faire Binney, and the niece of another silent picture star, Constance Binney. Born in Paris, educated at eastern finishing schools, Jackie followed the family theatrical tradition and had already had a small part in a film.

Two more basically diverse personalities can scarcely be imagined than Jackie and Dale; yet they fell deeply in love on that Saturday night. Dale phoned her on Sunday, took her for a drive Monday, proposed Tuesday and they were married three weeks from the day they first met.

Marriage counselors studying this young pair would have noted the serious clash in personalities and advised a much longer period of courtship, particularly since Dale is the son of divorced parents, has been divorced himself. They would have recognized Jackie’s dependent and too sensitive nature, her desire to be the center of attention, her need to have decisions made for her. And the experts would have insisted on a leisurely honeymoon so that the newlyweds could get to know one another in a tranquil atmosphere.

Instead, Dale made his first and most serious error. He selected Santa Barbara for the one-day honeymoon because a horse show was in progress. So they spent the day inspecting thoroughbreds! Next day he was back on the movie lot.

But it wasn’t his fault that he already had a house for his bride. Now, every new bride wants a hand in selecting furnishings for her first home. Installed as mistress in Dale’s bachelor cottage in Reseda, Jackie found a completely furnished house—even to the decor in the master bedroom—wallpaper featuring horse heads in masculine hues. The expensively brought up bride may have desired a bit more elegance in her honeymoon domicile—one closer to her friends’, but she was content. “It keeps the rain off,” Dale had told her, “and when you’re in love, what more do you need?”

Jackie found she needed experience in dealing with the butcher and the baker. She was completely untrained for her duties as a homemaker; had to start by learning to make coffee. Dale, with the example of an extremely competent mother, found this a trying period. In addition, unpunctuality bothers Dale, and Jackie in those days was perennially unpunctual.

Jackie for her part recognized immediately that Dale’s fundamental concept of wedded bliss did not coincide with hers and so she, like many a bride before her, resorted to gentle nagging in an effort to remake Dale closer to her heart’s desire.

“If there’s one thing an outdoor man can’t stand,” Dale remarked gloomily at the time, “it’s to have a woman a-naggin’ at him all the time. I don’t like to be questioned too much. Such as ‘What time will you be home for dinner tonight?’ How do I know? I don’t blame a woman for dislikin’ housework—I’m sure no help in that department. But if a wife dumps her household woes on a husband—they’ll sure end up arguing. The minute a woman makes a man feel he’s hooked by his suspenders, begins the ‘Don’t do this. Don’t do that’ routine she’s bustin’ up a perfectly good marriage.”

As a man of controlled emotions with a talent for composure, Dale, during those early days, found that his moody periods upset his wife “Jackie expects me to be a little more attentive and a little more conscious that she’s around. I may not act like it but I’m very conscious of her. Sometimes I sit silent for long periods thinking things out, just as you would riding alone in the Oklahoma back trails. But Jackie misunderstands. I’ve explained to her that these moody periods are part of the Irish in me, have nothing to do with her at all.”

All these differences in viewpoint, large and small, are in the past now, both the Robertsons admit—but while they lasted, life was pretty rugged for both. Yet Hollywood was shocked when, little more than a year after their marriage, they separated. Even the birth of baby Rochelle hadn’t helped. At the time Dale confided to a friend, “Our troubles have been going on almost since we married. It hasn’t been pleasant for either of us and we’ve tried hard to work out our problems. We almost separated a couple of times before, but didn’t. Fundamentally we love each other. And even now, we’re a long way from talking about a divorce.”

A week later the Robertsons, a little wiser in the ways of marriage, were back together. And they’ve remained together and courageously undertaken to solve their marital problems because of two basic facts: their very real love for each other and their abiding love for their baby.

They’ve learned to make compromises, to give a little, forget a little, and approach the future knowing that a true marriage is not “oneness” but “weness.”

“One thing I’ve learned,” Jackie says seriously, “is not to pay attention to irresponsible columnists who have tried to make a triangle of our marriage ever since it started. Dale is home seven nights a week so I know this gossip is pure fabrication. Not long ago, for example, Dale and I went to Las Vegas for the wedding of Dale’s double, Tom McDonough, who was best man at our own wedding. One column intimated that Dale had spent cozy hours with an entertainer. She happens to be the sister-in-law of Tom’s wife, and we were all together in a group. Another paper said I’d gone to Las Vegas for a divorce! Still another crazy rumor was that Dale punched his best friend in the nose. The truth was that a wedding guest had had too much to drink. Dale, in order not to embarrass the others, had led the man outside.

“Then there was that fantastic story linking Dale with Rita Hayworth! She denied the rumor, explaining that not only had she never met him but she’d never even seen him in a film. The only amusing thing about that malicious story was when Dale remarked ‘I wish she’d eliminated that last part!’ ”

And the press, it appears, may also eliminate stories speculating on any unhappy future for Mr. and Mrs. Dale Robertson. For both feel they can count on many more anniversaries to come.

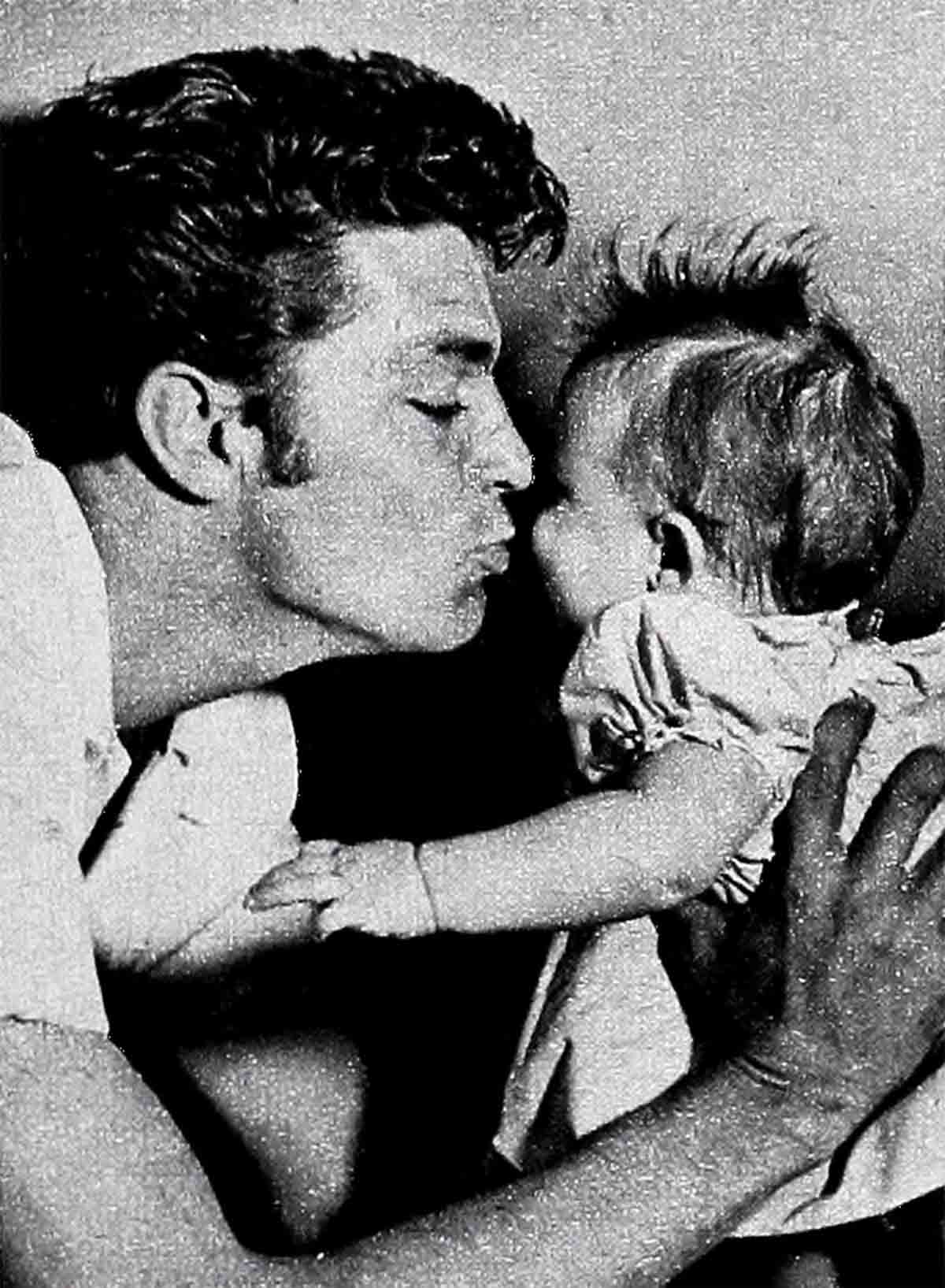

A strong factor in that belief is their feeling for little sturdy bright-eyed Rochelle. It is plain to see that young as she is, every day is Father’s Day with Rochelle.

And as Dale holds the baby on his lap his proud smile shows, better than words, that he considers her the most remarkable baby in the world. “Sweetest little girl in the world” is what Dale calls her when he doesn’t refer to her simply as “Young.”

There’s something else new with the Robertsons. “Jackie,” Dale says, “is becoming a much better cook. She turns out a dog-gone good meat loaf. And since Mom gave her some lessons, I don’t think I’ll have to go clear back to Oklahoma to sample a mess of crisp fried catfish and hoecakes.”

Hollywood needn’t worry about the Robertsons. The truth is that Dale and Jackie have found out (though admittedly the hard way) that life does begin with marriage!

THE END

—BY JANE CORWIN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1953