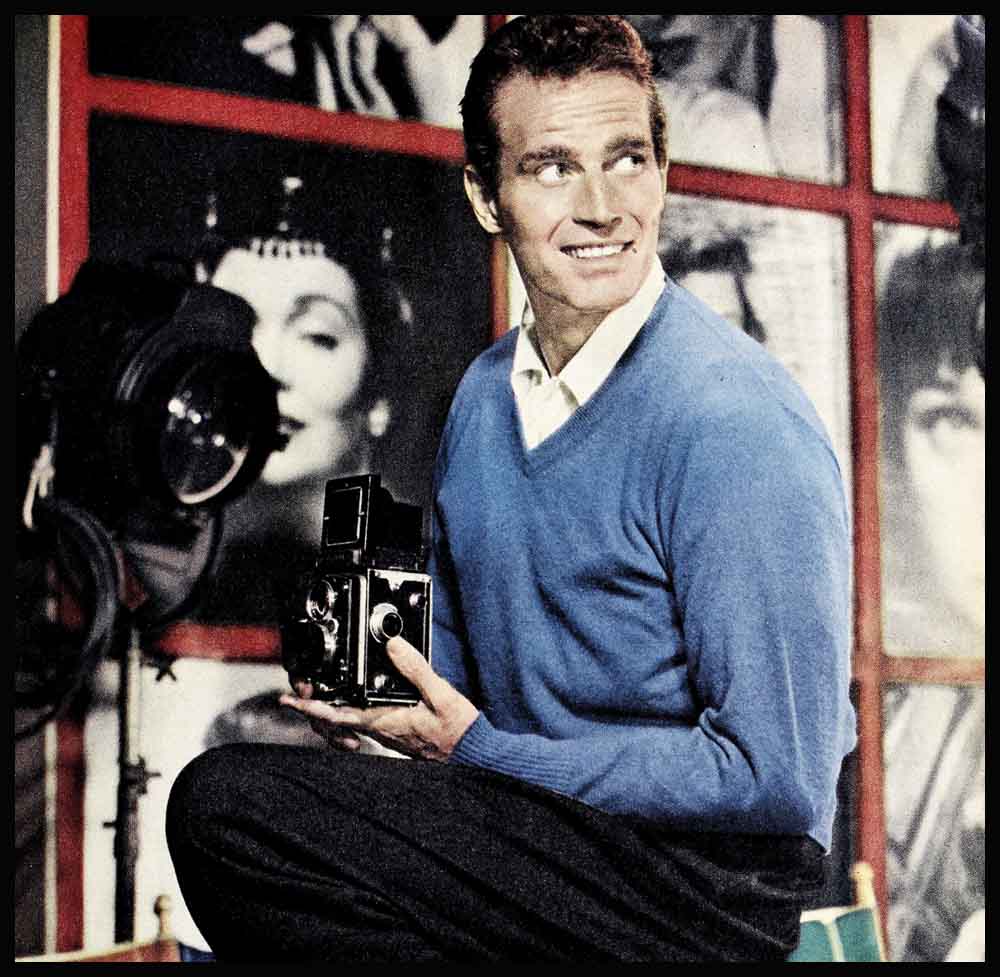

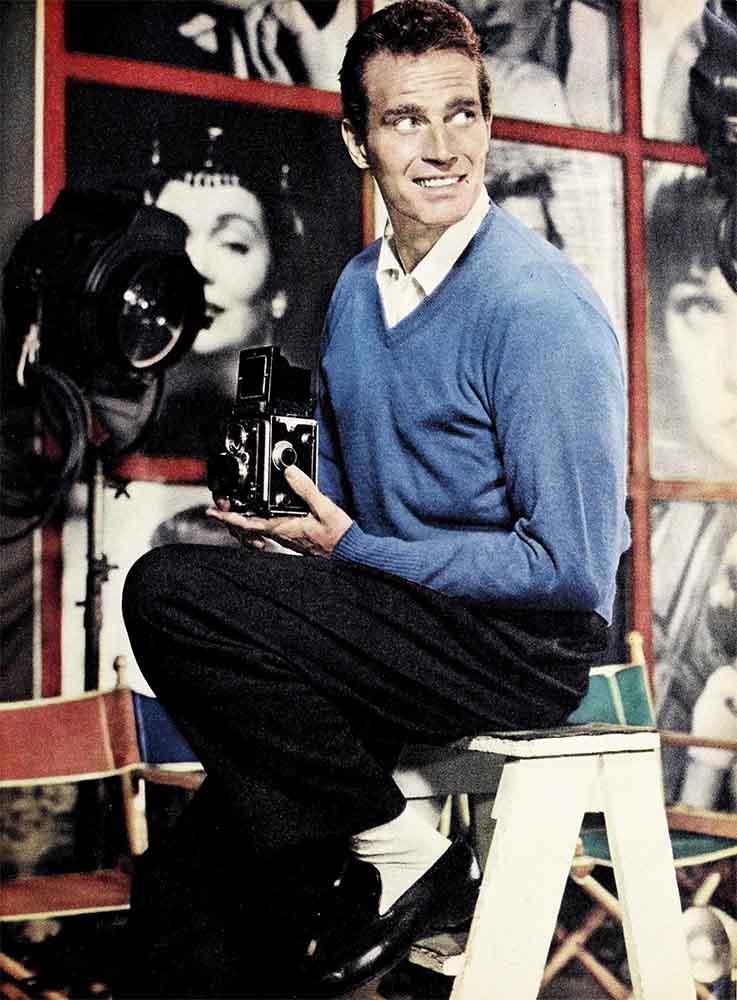

Charlton Heston Sounds Off On Men And Matrimony

“I suppose there are some people who think Lydia and I are old-fashioned,” Chuck Heston said quietly, “naive, perhaps, because we believe in the sanctity of marriage, and that there can be no double Standard for two people who really love each other.” Heston paused as if he were considering his next remarks carefully. “Perhaps I’m puritanical, but I can’t agree with the conduct of European husbands who boast that a flirtation—even an affair—with another woman is all right as long as their wives don’t know about it, and it is done discreetly. I’m glad that American women won’t stand for that, glad that most American husbands have a deeper respect for their wives.”

AUDIO BOOK

The next question was impertinent, but it seemed the place to ask it. Why had he been faithful to Lydia?

Chuck’s answer was straightforward and honest.

“It’s very simple,” he said, undisturbed by the question. “I’ve been in love with Lydia since I was seventeen. And the reason I’ve never cheated and never wanted to is that I happen to like my marriage. Nothing would be worth jeopardizing it. I know, too, that if I were unfaithful it would destroy everything I believe in. And, besides, who wants to land on the front pages of every newspaper in the country and wreck his career?

“There are other reasons, too,” Chuck pointed out. “I think it goes back to one’s childhood almost. I was brought up by parents who believed in ‘clean living and Sunday churchgoing,’ in honesty and integrity. When we came down from the woods of Michigan to Illinois so that I could attend high school, I was what you’d call a country bumpkin—big, gangling and green.”

The change was great for the teen-age boy who had spent most of his life alone, roaming the beautiful wooded areas that belonged to his family. At New Trier High School in Winnetka, Chuck found himself left out. “The kids in school were a smart lot. They had cars to race around in and parties on their minds. I was homely and self-conscious,” Chuck recalls, perhaps with some exaggeration. “My hair hung in my eyes and more often than not I was broke. I never felt I wanted to belong to a crowd like that.”

Looking back, it seems unbelievable that Chuck never had a date all through high school. But it’s true. “Books and acting cluttered my mind, not girls or parties. In fact, at the one affair I did go to—the big graduation dance—I didn’t last long. My parents drove me over to the school auditorium and dropped me off. I wasn’t too keen on going in but didn’t have much choice. After taking one brief look at the laughing crowd, I turned around and fled. This simply was not my kind of fun. Still isn’t. I’m a homebody, I like to putter around the house, listen to music, sometimes cook up a batch of spaghetti, play with Fray.”

When Chuck entered Northwestern University, though, something special did happen to the country boy from Michigan. Sitting two rows in front of him in Fundamentals of Theatre Practice B40 was pert, dark-haired Lydia Clarke. “I remember even the sprig of artificial holly she wore—that first day I saw her,” Heston fondly recalls. But he kept his admiration to himself until one afternoon after class when Lydia casually asked him how she should speak her opening line in their one-act play. The line was (Chuck’s never forgotten it): “My frog is dead.” He suggested she say: “My frog is dead,” with emphasis on the frog. That did it—Chuck fell in love.

The next time Lydia wandered backstage after a school performance, Chuck was ready. He fumbled but managed in the end to finally get a date. “It was wonderful,” he says, “and terrible.

“I didn’t have a cent in my pocket. So I took Lydia to the college hangout, Crossing my fingers I’d meet someone I knew there. Luckily, I did and I borrowed a dime. Lydia and I had one cup of coffee each, over three hours of talk about everything from Shakespeare to Barrymore. It was the cheapest date we’ve ever had.”

Chuck maintains—rather emphatically in fact—that he knew from the start that Lydia was right for him. “She was sincere about everything—or tried to be—and kind and warmhearted. Also, we’d had the same kind of upbringing.” For the next three years, Chuck proposed to Lydia regularly, and just as regularly she refused. Since then, Lydia admits that she thought the big lanky woodsman from Michigan looked as wild as the woods he’d come from. Besides, she was young and marriage was not in her plans. The theatre was her love.

It was wartime and Chuck was in the Army Air Corps and his morale had sunk to its lowest. “I’d just given up all hope of Lydia’s consenting,” Chuck says, “when one morning I received a wire: I HAVE DECIDED TO ACCEPT YOUR PROPOSAL.”

They were married in Greensboro, North Carolina, on March 17, 1944, just before Chuck left for overseas duty. “Lydia wore a lavender suit with a flowered hat. On the way to the church we got caught in a sudden downpour. The flowers wilted and the suit was limp and I expected tears. All Lydia could say was, ‘If only they’d been real flowers, it might have done them some good.’ ”

After his discharge at the end of the war, Chuck and Lydia went to Asheville, North Carolina, as co-directors and leads in the Thomas Wolfe Memorial Theatre. But Broadway had always been their goal and with only dreams they went to New York, where they found a thirty-dollar-a-month cold-water flat. “We shopped frugally for bargains at the supermarkets and struggled valiantly for a niche in the acting profession,” Chuck says.

Bit parts, a television walk-on came their way. And, about this time, other women began to notice the tali, good-looking young actor, Charlton Heston.

How did Chuck feel about his sudden popularity?

“I felt then as I do now and as I did even in high school,” he says. “I like attractive women and enjoy their company at a party but I don’t want to enter into any relationship outside of marriage that isn’t a purely friendly and platonic one. Anything else is out.

“But don’t misunderstand me,” he quickly goes on to add. “I’m as appreciative of a pretty girl as the next man. That’s normal. But it’s upbringing, a sense of right and wrong, or honor, if you will, that makes an extramarital relationship to me so repugnant.”

And how should a wife feel about the fact that other women might be attracted to her husband and that he might find them interesting?

Heston claims it depends upon the husband. “Lydia knows perfectly well that she is my love—in fact my first love. And, I think, that means everything.”

“How do you make Lydia feel secure in such a situation?”

“That’s difficult for a husband to answer,” Chuck says, pausing to consider the question. “But I suppose it’s being aware of her as a person. To let her know that you appreciate the way she thinks and the way she looks. To let her know that you enjoy talking over your ideas, your problems with her and that you recognize that as an individual she has needs—to feel loved, to feel wanted, to feel important in her own right. That’s why I never would ask Lydia to give up a play in which she was interested. I suppose being aware of the little things that women think important and that men often don’t understand is necessary for a happy marriage. Things like smiling at your wife across a crowded room when you’ve separated at a party, or holding her hand when she seems overwrought or afraid, or remembering important days and noticing how hard she may have worked getting the slipcovers to fit. I guess it all adds up to thinking less of yourself and more of the other person.”

“But isn’t Lydia ever jealous?” we prompted.

“I don’t think she’d mind if I told you. Yes, Lydia has been at times. But I think that’s only natural—for any of us. But, fortunate for me, Lydia’s a fine actress. She seldom displays her jealousy. Unlike some couples, we never have any after-the-party-is-over arguments. You know, the guests have gone home and the wife snaps: ‘Why were you so attentive to that young niece of Bill Jones?’ ”

In their early struggling days, Chuck scarcely had time to give another woman a tumble. He was too busy. There was one television job after another. First commercials, then small dramatic roles and finally meaty leads. In 1950, Hollywood beckoned and Chuck made his first film, “Dark City,” opposite Lizabeth Scott.

The results were new roles and his career began to flourish. In the meantime, Lydia was becoming a well-known stage actress and the Hestons discovered they were spending more time apart than together. For instance, when Lydia was in Chicago with the hit, “The Seven Year Itch,” Chuck was shuttling between New York for television and Hollywood for movies. For ten years, though, they kept their marriage solvent and their love alive through marital hazards which should have defeated both.

“The most important thing is to marry the right person in the first place,” says Chuck. “From the very beginning, Lydia and I had a great bond—our love for the theatre. Lydia’s success was as important to me as mine was to her. And strange as it may sound, it was her success that deepened my respect for her. It’s possible to respect someone you don’t love,” Chuck went on, “but it’s hard to love someone you don’t respect. I have the greatest respect for Lydia’s work and the things that are important to her. And, we’ve been lucky, we’ve been willing to compromise.”

“But an actor has more problems than the average husband, don’t you agree?” we interjected. “For instance, as your career flourished and you found yourself before the cameras with many lovely Hollywood stars like Jennifer Jones, Susan Hayward, Eleanor Parker, Anne Baxter. Didn’t they intrigue you?”

“Certainly,” Chuck candidly replied. “But no more than any other lovely creature. It may seem ridiculous to compare a pretty actress to a fine thoroughbred, but beauty and perfection are the same in any form of life. They’re all God’s work.

“Sure, some actors get carried away by the charms of their leading ladies and wind up getting cozy after the klieg lights are out. But this happens in offices, in plants, in places all over the world where men and women work together. Acting is work, an actor has to be as professional as, say, a worker in a steel plant. A steel worker has to learn to handle his product. He wears protector gloves, an asbestos apron, a mask. Sex is what sells tickets at the box office, but an actor must learn how to handle it.

“For instance, I refuse to pose for stills with actresses playing opposite me unless the photographer takes us on the set in costume. I turn thumbs down on photographs of myself and rising starlets, and I always insist publicity shots are with two actresses instead of one. If any actor poses with only one lovely girl, chances are, a gossip columnist will pick it up and make a news item out of it. With two, well, it’s not so easy.

“Yes,” Chuck declared, shifting his long legs under the table, “there are a hundred opportunities for an actor to cheat. But why? An intelligent actor realizes that most women aren’t really interested in the man himself, but in his name. In our profession, you soon learn there are certain women who collect romances with famous names like other women collect Dresden teacups. It’s not very flattering to any man to feel he’s nothing but a trophy to be won and then put on a shelf. But then again doesn’t any intelligent man realize this? Love is made up of lots of things: devotion, beauty, strength, loyalty, sacrifice, understanding. It’s life itself. Who, in his right mind, would jeopardize all this for a casual fling? I’ve yet to meet a married man who was unfaithful to his wife who wasn’t, at heart, discouraged with himself.

“You’ve got to know what you want and realize when you have it,” Chuck explained seriously. “Then there’s rarely a situation you can’t handle.”

“What about the enamored young ladies who somehow get hold of a star’s telephone number?”

Chuck laughed loudly. “It happens to almost every actor. Usually when you’re out of town, generally on a personal appearance tour, when you’re staying at a local hotel.”

“How do you handle it?”

“I use Dick Powell’s famous line,” Chuck replied, with an impish grin. “Dick always answers, ‘Gee, honey, I’d love to meet you Just a minute. Wait till I ask my wife.’ The girl invariably hangs up.

“No, I have an easy working formula. Kiss your leading lady in the morning, lock yourself up in your dressing room for lunch; kiss her again in the afternoon. By six o’clock when the director says, ‘Wrap it up,’ you’re ready to go home—to the woman you know best, the woman who’s gone through laughter and tears with you, the woman you love. And as the years go by, you’ll realize that no outside flirtation, with its brief superficial pleasures, can solve boredom or personal problems nor can an affair possibly compare with the contentment, the richness and the happiness of a constant marriage.”

Thirteen years of marriage without a single whisper of gossip for the Charlton Hestons has proved this is a pretty good formula. Particularly when it can be made to work in Hollywood.

THE END

—BY PATTY DE ROULF

DON’T FAIL TO SEE: Charlton Heston in Paramount’s “Three Violent People.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1957

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments