Love On The Run—Don Murray & Hope Lange

When Don Murray flew out to Hollywood to become Marilyn Monroe’s leading man in “Bus Stop,” he was a very happy and excited young fellow. Not because of Marilyn Monroe. Not because of his big movie break. But because of a cute little lady named Hope Lange. “After five years of pleading, reasoning and battling with her,” Don states, with a proud gleam in his eye, “Hope finally agreed to marry me.”

But that was only the beginning. These lovebirds-suddenly-in-a-hurry have had to make up for the five years of dawdling. While Don was working in “Bus Stop” in April he was granted a day or so off to get married. A few hours later he was on his way to Arizona for location. Then back to Hollywood. When the picture was done he and Hope flew to New York, had the religious ceremony to seal their mating, had to cut the honeymoon short when Don flew back to the Coast for his next film, “Bachelor Party.” Tied up in a melee of unfinished packing and dental appointments, Hope couldn’t join him until a week later. And to top it off, the happy pair have discovered that they are headed for parenthood—in February!

Winning and wedding the woman you love, according to Don, can be mighty strenuous when it’s combined with landing your first starring roles in the movies. In fact, the career part was, comparatively, a cinch. The way Don had it figured, he was sure to arrive in pictures sooner or later.

You see, this handsome specimen of young manhood really couldn’t miss. He grew up in the theatre. His father, Dennis Murray, was and still is a well-known director. His mother, Ethel Cook, belonged to that picked group of the most glamorous females in show business, the Ziegfeld Follies girls. Don was born right in Hollywood, because his father happened to be working as a dance director at Fox at the time. The time was 1929. He was given the full moniker of Donald Patrick Murray. Twenty-six years later, like his father before him, Don signed his first movie contract with 20th Century-Fox. But his life has been full of such coincidences. . . .

When Don was nine months old, the Murray family had trekked back East on account of the depression, and Don got his early schooling wherever his dad found employment—Manhattan, Fort Worth, Cleveland. Finally, the family—there was an older brother, Bill, and a young sister, Ethelyn—settled in East Rockaway out on Long Island, and Don became an average high-school student.

Well, maybe not So average. . .

“I loved to clown,” Don confesses. “I’d hate to tell you how many times I was sent to the principal’s office for cutting up.”

When graduation drew near, the fellows on the football team buttonholed the comic. “Listen, bub,” they threatened. “No clowning when we walk up to get that diploma. We’re all graduating by a slim margin. If you louse us up, we’ll murder you!

On the big day, Don appeared as serious and as dignified as a professor. His buddies were startled at his unexpected, sober performance, broke into snickers and snorts and almost wrecked the graduation themselves.

In high school Don had two chief interests—sports and drama. In the first category, he excelled as a long-distance track runner, won his letter in football and played a speedy basketball game. In the second department, he began as early as his freshman year to write and direct skits.

“It was easy,” Don relates. “I dug through a lot of scripts my dad had stored in a trunk. I stole a joke from one, another joke from the next, wrote new lyrics to old songs and figured out a simple plot. Overnight, I had myself a show.”

The only trouble was that the youthful writer-director didn’t feel his fellow students were doing justice to his plays. “So I decided to act in them myself,” he concludes.

Or course, this wasn’t the first time Don had performed. Many years before, when his three-year-old sister was attending a dancing school, the teacher sent out an SOS for a small boy to appear in the annual school presentation. Don, aged six, was corralled. His job was to hide behind a large umbrella while the little tykes danced merrily away. At the end of the number, the umbrella collapsed, Don stepped forth, grabbed the prima ballerina and ardently kissed her.

Perhaps Don’s parents had been aware of their son’s acting talents from that early age, for they loyally attended all of his high-school performances and constantly encouraged him to work toward the theatre.

“When I graduated,” says Don, “it was a toss-up whether I’d go to college in order to get into semi-professional basketball or enroll in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York and study acting. But I guess greasepaint was in my blood. The Academy won out.”

Two things surprised young Don Murray when he started at the Academy. He was astonished to see the adolescent would-be actors and actresses spending countless hours discussing the theatre, psychoanalyzing themselves and everyone in the profession, and dressing to the hilt, as though they already were great stars. But the biggest surprise was to discover that he, Don Murray, was not a comedian, as he had always believed, but a serious actor.

It happened when he was cast as a tragic Scotsman in “The Hasty Heart.” All of a sudden, the directors at the Academy were taking notice of the youth. The well-known drama coach, Paton Price, saw Murray in “The Hasty Heart” and immediately got him a job in summer stock.

But don’t think Don was one of these characters who was completely devoted to his art. No, indeed! While he was studying dramatics, he also worked as an usher at CBS and played semi-pro basketball. In the midst of this hectic routine, a Universal Pictures talent scout caught one of his Academy performances and flew him out to Hollywood to test for a juicy part in “Bright Victory.” When the test was over, the studio decided Don, just eighteen, was too young for the role.

“However,” said the executives, “we’ll give you a contract. A nice ten-year contract. We’ll train you, build you up, shape you into something colossal.”

Even in those days, Don Murray knew what he wanted. “I don’t want to be tied to a cold business deal like that,” he brazenly told the bigwigs. “I consider acting an art, not a profession.”

“See here,” snapped the executives, “you’re not Marlon Brando.”

“Well,” shrugged Don, “I’ll go back to New York until I am!”

And thus the proud young man hot-footed it back East, studied some more at the Academy, and wore out several pairs of shoes making the rounds of agents and He landed a few magazine modeling jobs and performed in spot commercials for television. Then one day he had an appointment to read for Tennessee Williams, who was casting “The Rose Tattoo.” Williams listened to Don about ten minutes, tossed aside his script and declared, “I’ll sign you for the role of the sailor.”

It was while Don was playing on Broadway in “The Rose Tattoo” that he and another chap went out on a double date. His friend’s date was a pert, petite blond, Hope Lange. A couple of weeks later, Don went to a party. Hope happened to be present.

“Would you like to see ‘The Rose Tattoo’ some time?” Don invited.

“Yes,” Hope smiled.

Don got Hope a ticket the very next evening. After the show, he took her out to supper. “We sat up until three o’clock in the morning, talking,” Don recalls. Talking about what? “Art!” Don laughs. “But,” he confesses, “I knew from that moment on that Hope was going to be my wife. Maybe she didn’t realize it. After all, she was still in junior college. I knew I’d have to wait until she grew up.”

And wait he did. But when Don decides a thing, brother, that’s it! When he went on tour with the Williams play, he barraged Hope with letters. She didn’t answer many of them, but that didn’t make any difference to Don. He had made up his mind.

Like most healthy males, Don received a greeting from his draft board along about then. Because of his religion, he was listed as a conscientious objector and was assigned two grueling years of service as a social worker in European refugee camps.

“That was a great experience,” recalls Don. “I can speak German and Italian fairly well and I got to really know the people in the German and Italian camps. My duty was up in Christmas of 1954, but I had just organized a special holiday show for a camp in Naples. The refugees were eagerly anticipating the production, and I didn’t have the heart to let them down. I ended up staying another six months.”

When Don Murray finally stepped down the gangplank in New York in May 1955, who was there to meet him? Hope, of course!

“He looked terrific and he looked terrible!” remembers Hope. “I was thrilled to see him, but at the same time, he had been ill in Europe and he was as thin as a rail.”

Immediately, Don took up his campaign for marriage. Hope still hedged. “I just wasn’t sure of myself,” Hope explains. “Don was a wonderful boy, but I couldn’t see myself settling down.”

Because Hope wouldn’t say the magic word, innumerable spats ensued. On each occasion, Don would stalk off, vowing, “This is the end! Goodbye, Hope. You’ll never see me again!”

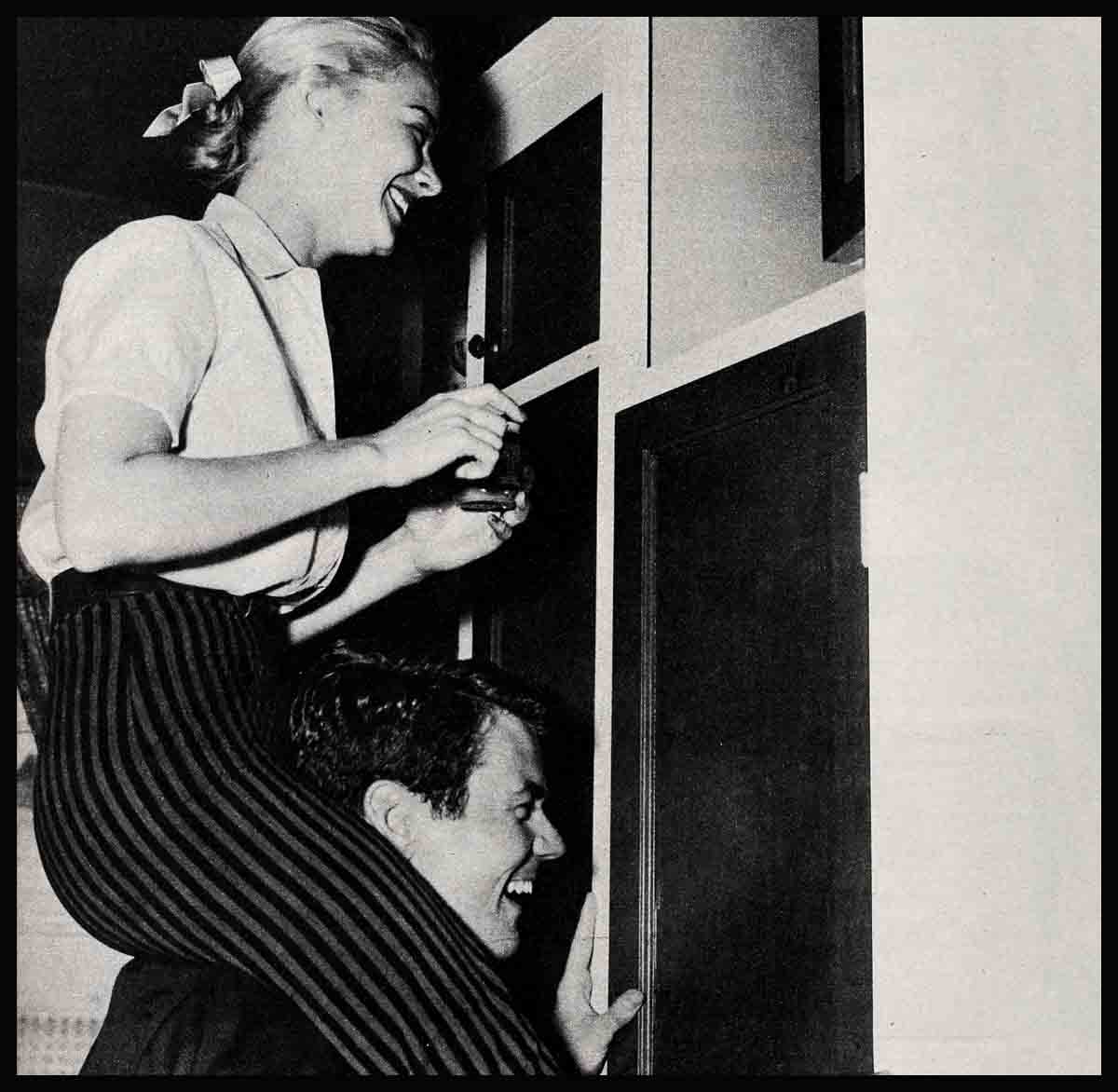

After one of these lovers’ quarrels, Don suddenly remembered the large French windows in Hope’s first-floor apartment. “Why, anybody could just walk in off the street!” he began to conjecture. The more he thought about the windows, the more he worried. With visions of Hope being strangled in the black of the night, he sought his dad’s aid and, together, they constructed a special lock. “But who will install the lock?” Don pondered. “Her brother-in-law? My dad? Or me. . .?”

Me won out. Don phoned Hope, explaining he wanted to put a lock on the unsafe windows. Hope agreed to let him come over. The lock was duly installed. The lovebirds kissed and made up.

That’s the way it went. Two kids in love, bickering violently and arriving at peace terms a week later. Then along came a play called “The Hot Corner.” Don was signed to a part and he begged, plotted and pulled strings until he got Hope on the payroll as an understudy. “We didn’t let the rest of the company know we’d been acquainted for years,” says Don. “So when they saw us going out on dates, they thought the play had brought us romantically together.”

Without realizing what was happening, Don and Hope got so busy with their roles in “The Hot Corner” that they forgot to argue about marriage. Then the show folded in Boston, and on a cold, rainy February afternoon, the pair returned to New York.

“Say,’ mentioned Don casually, “don’t you think it’s about time we got married?”

“Maybe,” replied Hope.

Don went into one of his filibusters and by four A.M. Hope had weakened and said, “Yes.”

Coincidences already had been popping up in the young couple’s lives. They discovered accidentally that their fathers had known each other in show business years ago. On New Year’s Eve, when their families attended “The Hot Corner,” Don’s leading lady unexpectedly fell ill and Hope got her first chance to act opposite Don in public. “Their love scenes were magnificent!” recalls Hope’s sister, Minelda, who was present at this momentous event.

Don and Hope also appeared together in a TV play in New York quite by chance. Movie studios were beginning to sit up and watch them individually. Don had worked in the television version of “The Skin of Our Teeth” and had just done a Kraft show when Joshua Logan singled him out for the role of Bo in the film production of “Bus Stop.” Simultaneously, several studios had been negotiating with Hope. Although it sounds stranger than fiction, a 20th Century-Fox talent scout wanted her for the part of Elma in “Bus Stop.”

This activity was all happening in the late winter of 1955. Don and Hope were already engaged. The wedding was only a matter of deciding when and where. But with commitments and contracts flying around fast and furious, the young couple scarcely had time to set the date. Don flew to the coast to act opposite Marilyn Monroe. Hope followed to do TV. Don signed a contract with 20th Century-Fox—the kind of contract he’d always wanted. Two pictures a year and twelve months off every second year to do stage work. When his studio offered Hope the same kind of contract, she happily signed on the dotted line. A few weeks later, both signed another contract—marriage. They had a quiet, civil ceremony in Hollywood on April 14, 1956. Three months later, on June ninth, there was a double-ring church wedding in New York.

“Hollywood was both fascinating and frustrating,” admits Don. “I had been accustomed to the theatre and live television where you either do or die. But on a movie set, everything is upside down. You start with a scene in the middle of the script, switch to the last scene in the film, wind up with the opening shot.

“Once,” he continues, “I thought I’d played a scene as well as I ever would. But after the director said, ‘Cut,’ there was a protest from the technicians. ‘We didn’t get a good snow effect!” So we all waited until the artificial snow was going full blast and then shot the whole scene over again.”

Playing opposite Marilyn Monroe, according to Don, was a wonderful experience. “She never went temperamental. She always agreed with the director. And she was the most patient person I’ve ever met,” recalls Murray. “When I happened to muff a scene, she’d just smile and say, ‘Let’s try it over, shall we?’ ”

Actually, it’s a miracle that Don ever got through “Bus Stop.” He had endured a bad siege of pneumonia while in Italy and, although he didn’t know it, fluid was still in his lungs when he went to Hollywood. Two days before shooting began, the old illness acted up—high temperature, dizzy spells, weakness. But, gamely, Don was determined to go on. His drama coach, Paton Price, flew to the Coast to help out, got him dressed and drove him to the studio every morning. Joshua Logan shot scenes around: him when he was at his worst. Hope arrived at his apartment regularly around six to cook him hot meals and see that he got to bed early.

“Don Murray’s a trouper if I ever saw one!” commented Logan, when the picture was in the cans.

In June, Mr. and Mrs. Don Murray returned East for their second wedding ceremony and their first real honeymoon. He was well again, “Bus Stop” was completed and at last, the couple had time to relax.

Hope now decided to go on a campaign of her own, determined to fatten up her new hubby and garb him in clothes befitting a leading man.

“Don used to be picky about his food,” she explains. “He’s six foot, one and a half inches tall and weighs a scant 170. I stuff him with scrambled eggs, fried tomatoes, bacon and English muffins with plenty of butter at breakfast. I insist he eat a good lunch and at dinner I give him a big, nourishing stew or steak and potatoes and huge hunks of pie.”

“She’s a good cook,” says Don admiringly. “She can take a plain piece of filet of fish and make it taste like a fancy dish at Ciro’s.”

In the clothes department, Hope reveals, “Don has always been the world’s most miserable dresser. Purple socks, worn-out ties, suits that hung on him like sacks. Now I pick out his wardrobe, and I’m slowly getting him into shape.”

But slowly. Last July, Hope met her guy at a smart New York restaurant for luncheon. He looked neat and handsome in his tan summer suit, and she was very happy over the progress she had made. . . . until they left the restaurant and walked out on the street. Then, to her horror, she saw Don was wearing a shabby old pair of basketball shoes!

The Murrays have one goal, above all others. To have fun! “We swim together, dance, indulge in hectic badminton matches, love to listen to good music,” Don declares. “We plan to work together in pictures, if possible. And, surely, we’ll do a play together. Maybe even a musical. Hope’s a marvelous dancer. My mother was a singer and I’ve inherited a little of her talent.”

They also plan a home and children in the future. Right now, they live in Hope’s one-and-a-half-room apartment (the one with the windows) when they’re in New York and they rent a larger apartment in Hollywood.

One thing about this gay young pair—they know where they’re going and how they’re going to get there. As Hope’s sister, Minelda, says, “They both have high moral standards. They’ll never stoop to anything that isn’t right. Don doesn’t drink or smoke. In fact, he has a clause in his contract stating he will never endorse a tobacco or alcohol advertisement. Hope smokes a little and takes a cocktail. But I think Don’s example will change that.”

And, best of all, there isn’t the slightest suggestion of professional jealousy between the two. “If Hope wants to act, that’s all right with me,” Don has said. “All I care about is that she’s my wife.”

As for Hope . . . “I’m glad Don’s becoming famous,” she declares in all sincerity. “I’m in love with him and I’m very proud of him.”

THE END

—BY PATTY DE ROULF

YOU’LL ENJOY: Don Murray in “Bus Stop.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956