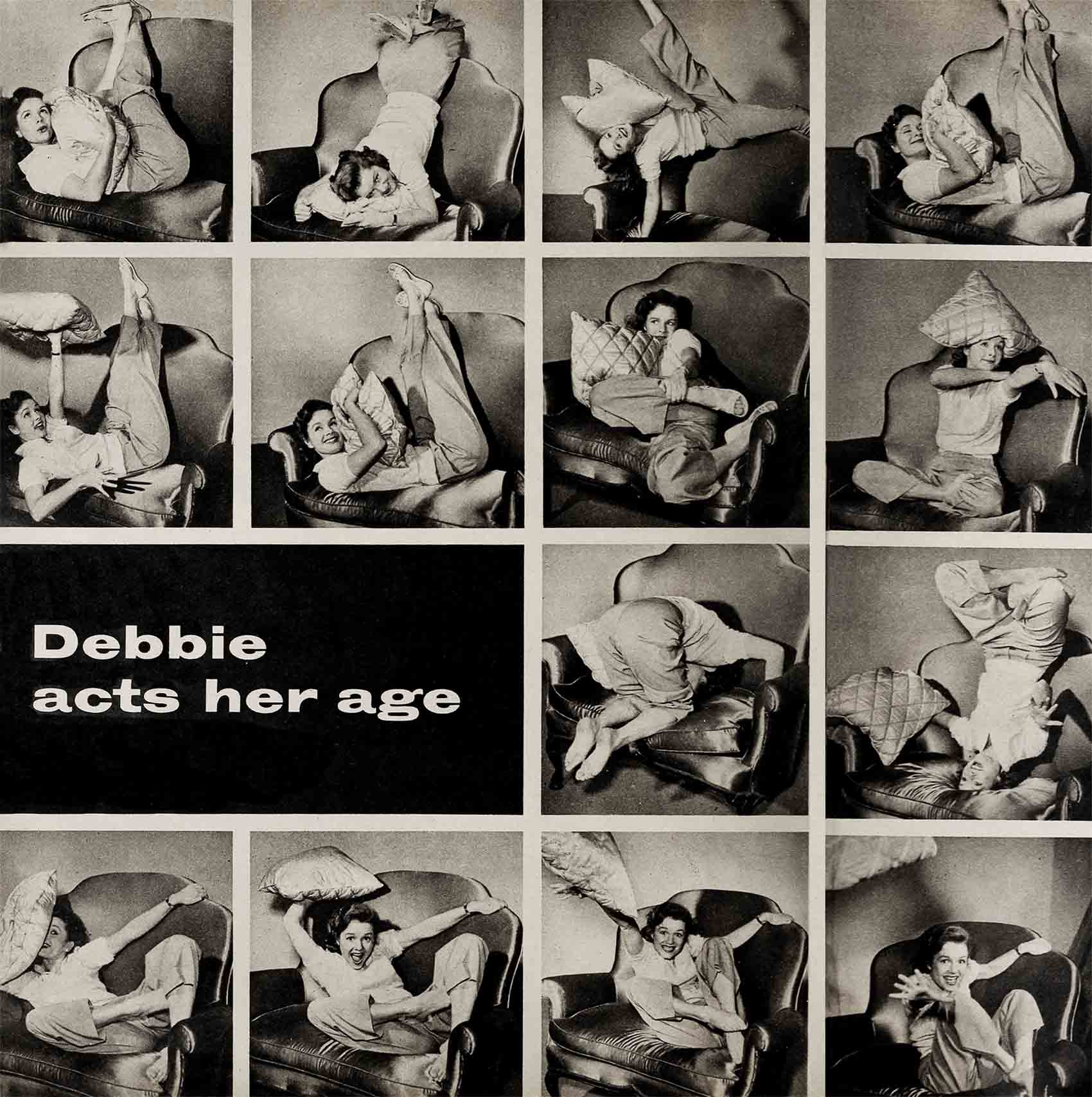

Debbie Reynolds Acts Her Age

Her feet were on the coffee table, which meant that Debbie was at home. In fact, she and her parents were engaged in a discussion of teen-agers—their problems and their fun—and Debbie was talking eagerly.

“You see, teen-agers feel that just because they are young doesn’t mean—” Debbie suddenly stopped and sat bolt upright. “Oh, brother!” she exploded.

“What’s the matter?” her mother wanted to know.

“Well—gee—I just remembered. In April I’ll be 20!”

The way she said it made it sound like 90, and Maxene Reynolds smiled to herself. “What’s so awful about becoming 20?”

“Don’t you see?” asked her daughter. “I won’t be a teen-ager any more!”

The conversation took place early this year, and since then Debbie has weathered her twentieth birthday without accumulating a mass of wrinkles, or suffering hardening of the arteries. But she was obviously reluctant to leave the golden days behind.

Debbie is the rare young girl who acts her age and doesn’t strain to ‘grow up.’ Despite all the hoopla about life beginning at 40, and the charm of a woman at 30, no one can deny that the girl in her teens and early twenties has a great treasure—the bloom and the freshness of youth. And youth has never been wasted on Debbie Reynolds, because while she is totally unconscious of the resultant charm, she lets nature take its course in the ‘matter of maturity.

She has never claimed to be older than she is, or to try on the veil of sophistication. “I only ask,” she says, “that people give me credit for being as old as I am. When I was 16 and began going out with boys my own age, everybody thought my dates were robbing the cradle.

I guess it was because I was small, and the nut of the crowd, but at any rate people thought I ought to be home reading ‘The Bobbsey Twins’.”

As a matter of fact, her mother despairs that Debbie will never grow up, that she is too imbued with the spirit of Peter Pan to be interested in exotic perfumes, sheer negligees and all the things that go with womanhood. Debbie confines herself to light perfumes, still clowns around the house, still collects monkeys, and sighs for the good old days when she had time to toot her French horn. She seems to cling to everything reminiscent of her school days, and once in a while will open her cedar chest and gaze sadly at the blackened chrome on her batons. The other night a girl friend came around with an offer to buy Debbie’s French horn, an instrument that is badly needed in a local band. “I just couldn’t,” said Debbie. “I can’t part with it. After all, some day I’ll have time to play it again. And. the piano, too.”

She continues to chew gum, noisily and with great gusto. She has conceded to her mother’s pleas in only one respect: she doesn’t chew in public. To Debbie, chewing is a relaxation, and when she comes home tired at night, she often climbs into bed with a book and a sizeable chunk of gum. She doesn’t smoke, and dislikes the odor of tobacco. “So when Pop smokes, I chew,” she says. “And I don’t pretend to chew gracefully. I just have a ball of a time.”

In subtle ways, Debbie is growing up. Few girls of her age pay any attention to politics, but Debbie, who has always been interested in the inner workings of her native Burbank, has widened her interests to national politics. Last year, on a trip to the Capital, she met and observed many of our top statesmen and attended a session of Congress. She came away with definite ideas, and is really interested in the voting privilege she will have next year.

On the lighter side, Debbie has finally bought a hat. Her purchase threw the entire household into a tizzie, for Debbie has always scorned any kind of headgear. She not only bought this chapeau, but she wore it, plus gloves, to three consecutive. social functions, and Maxene Reynolds sighed happily. “You know,” she said to her husband, “I think there’s finally a ray of hope after all.”

In years gone by, Debbie regarded babies as strange creatures. Lovable, but strange all the same. If you couldn’t talk with a character, or dance with a character, what kind of a character was it? Then she became an aunt, and on the day when the baby was left in her care, Debbie toted it over to Gene Kelly’s house and from there to MGM, carrying it proudly, and beaming at every compliment.

Debbie’s attitude has changed towards her brother, too. Bill had always been the big brother, the guy who knew everything and everybody, but with the passage of time Debbie has caught up with and even passed him in maturity. Now she refers to him as ‘my little brother’. Bill doesn’t object to this at all. On the contrary, he admires her tremendously.

Debbie’s mother and father no longer loom as strange and mystical overlords. In the past three years she has come to know them.as real people, to understand their problems and their moods. “I’ve even got to the point where I know how to work them for what I want,” she says, with a grin. Apparently this isn’t very difficult, for Ray and Maxene Reynolds have always let Debbie make her own decisions, so she has evolved into a self-reliant girl with sound judgment.

In the past, boys have suffered a lot of pangs over Debbie, and only now she is beginning to realize how unfairly she treated them. “I guess I was sort of scared of fellows then,” she says. “And when they’d ask me for a date I’d give them the brush-off. When I look back now, it strikes me I was pretty terrible. I don’t know why they even bothered to speak to me.” Or, in other words, she is no longer shy with the opposite sex.

Without being aware of it, Debbie is learning how to talk with people in all walks of life. In her position as a movie star, she’s met senators, farmers, lawyers, bricklayers, and the President. Debbie has always liked people, she used to sit on her street corner for hours at a time and watch people go by. But her recent contacts have taught her a lot and given her great poise. Debbie herself says, “Without a movie career, I would have been a jerk.”

But growing up has much to do with that, too. Debbie showed definite signs of an oldster when she recently advised a friend not to work so hard at school. The girl in question was bending under the burden of extra-curricular activities along with her regular studies.

“Stick to your schoolwork,” opined Miss Reynolds. “Don’t knock yourself out working for pins and letters. It isn’t worth it ”

Two years ago this same Miss Reynolds belonged to every club in school, collected pins and letters like mad, and joined every committee that would take her—and these things were important as life and death to her. But now, from her advanced position as an ex-teen-ager, she realizes that this hullabaloo isn’t worth all the trouble.

The neighborhood kids now look to her for advice on clothes and makeup. As the fashion oracle of Evergreen Street, she is a great help to them. They all borrow her clothes despite the fact that some of them (to Debbie’s amazement) are growing larger than she is. One girl, barely in her teens, was thrilled by Debbie’s offer to lend her a particularly devastating formal. Although she ate nothing all day in order to keep slim for the dress, Maxene and Debbie had to lay her out flat on Debbie’s bed in order to close the zipper. Another neighborhood girl, discouraged because of her complexion, came to Debbie for help one evening and Debbie gave her a full treatment, a la MGM.

One of the reasons Debbie acts her age is the fact that she has not gone Hollywood. Most actresses her age begin having flings about town with older men, and drape themselves in furs. Debbie sticks to dating boys two years older than she, realizing that she has more interests in common with people her own age, even though she can hold her own in an older crowd.

Debbie’s parents understandably have been concerned over the possibility that their daughter might go berserk with success, and Maxene Reynolds consulted her own mother one day late last spring. “Maybe I’m too close to Debbie to know,” she said. “You tell me, frankly, if she has changed with all this Hollywood business.”

“She certainly has,” said Debbie’s grandmother. “She takes much better care of her clothes. And her diction is better. But I can’t say the same for the way she keeps her room.”

Fortified by this assurance, Mrs. Reynolds took the plunge and suggested to Debbie that perhaps she might want to move into an apartment by herself. Maxene felt it was a plunge because she knows enough about Hollywood to know that when local girls make good and move out of their own homes, they are often on the road to losing their sense of values.

Debbie, though, was amazed at her mother’s suggestion. “Why should I move?” she demanded. “I don’t want to live in one of those elegrant places. I want to stay right here where I can kick off my shoes if I feel like it.”

Actually, Debbie has a distinct aversion to living alone. Ray Reynolds converted the double garage in the rear of their little property into a small guest house, thinking that Debbie might like it for quiet and study. But Debbie wouldn’t budge from her accustomed domicile. She just plain likes being with her family, and has stayed away only on those occasional nights when she works late at the studio and is dog tired. Then she shuns the 20-mile trip back to Burbank and stays with Miss Horn, her ex-teacher who lives in nearby Westwood. Sometimes when she is working on a picture Debbie sees little of her parents.

“Well! Look who’s here!” says Maxene when Debbie blows in after a few days’ absence. “Let’s see if you’ve changed any.”

Debbie works hard, as does any actress starting her way up the ladder, and even when she does come home, she wakens after. her father has left the house for work, and sometimes goes a whole week without seeing him. “I look in on you in the mornings sometimes,” says Ray Reynolds a little wistfully, “just to make sure you’re still alive.”

She forgoes her piano lessons to concentrate on the singing and dancing needed for movies, and gets so busy she forgets to eat. She manages to keep up her activities as honorary mayor of Burbank, and writes to as many servicemen in, Korea as time will allow. Despite her home ties, she wanted desperately to go to North Africa to entertain troops and cried when the doctor wouldn’t let her. For Debbie, there is never enough time, and often, she remarks, pensively, “I wish I were back at J. C. Penney’s,” (she sold blouses there on former summer vacations). “Life was so simple then.”

The “simple life” appeals to Debbie so strongly that she knocked the brass hats off the heads of Warner executives when she was at that studio. Laid off salary temporarily, she found her piggy bank was almost empty, and Christmas was just around the corner. So she went to work at Newberry’s, a novelty store of the five-and-dime variety. The studio called at home one day; she was out.

“Well, where is she?” they wanted to know.

“She’s working,” said Maxene Reynolds simply.

“Working! But she’s under contract to us. Where is she working?”

“The hardware counter at Newberry’s,” Maxene said, and the lid blew off. Debbie was taken to task for such unheard of action, and she listened to the lecture. in silence, uncomprehending. If it was Christmas and she needed money, and if Warners wasn’t paying her anything, she couldn’t see any reason why she shouldn’t toddle off and work wherever she pleased.

Hollywood just doesn’t impress Debbie, and neither does the flattery that is offered by strangers. The kids on Evergreen Street don’t bother. They know that if they were to say to Debbie, “Gee, you were great!”, she’d look at them as though they’d gone off their rocker. Because Debbie truly doesn’t think she’s great. On the other hand, if a friend says, “You know, you were sort of good in that scene,” Debbie beams because she can believe it. Sort of good, maybe, but great—never.

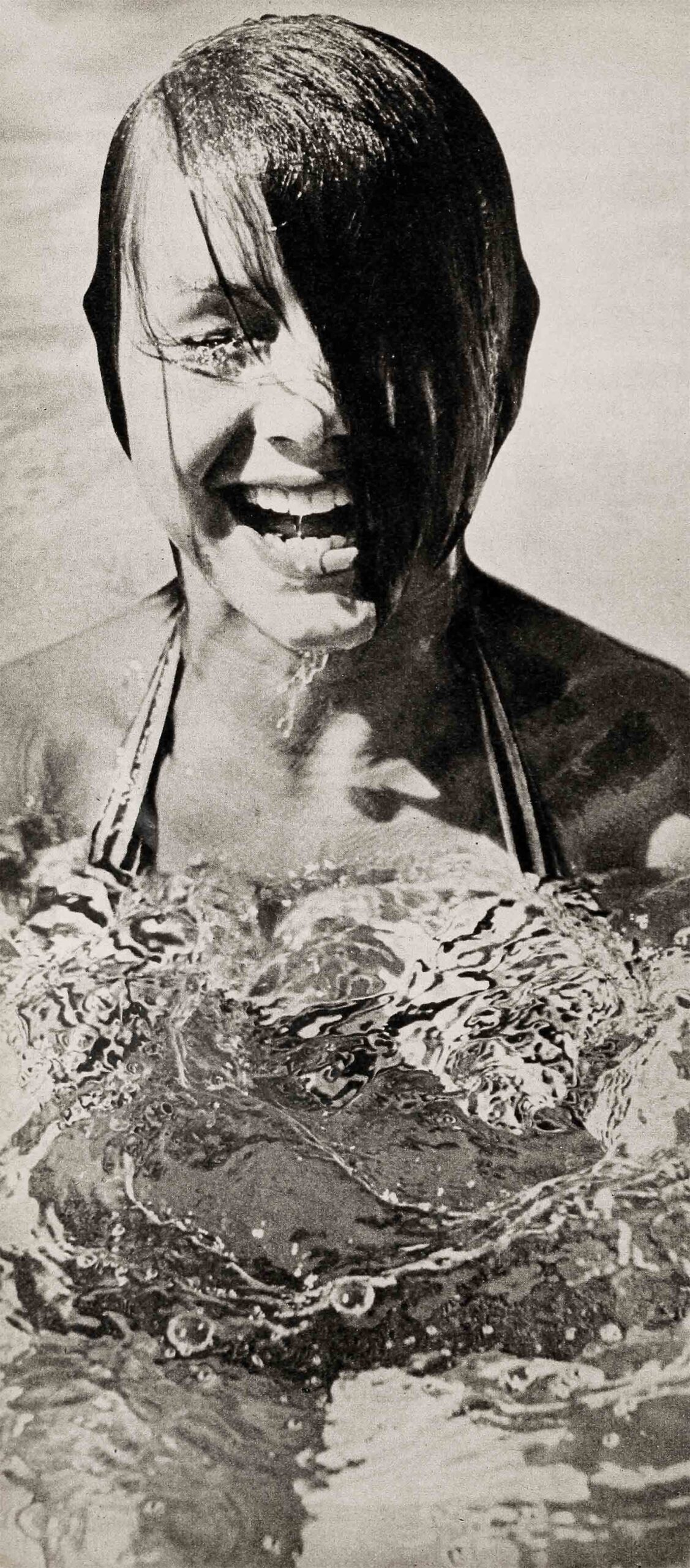

She is living two lives right now, her own and that of her work, and she is unaware that Hollywood is rubbing off on her the only way it could rub off on Debbie Reynolds. She has acquired poise and good grooming and considerable glamor, but through it all she continues to have the appeal of the purity of youth.

Debbie doesn’t look forward to being sophisticated. There’s only one milestone she wonders about. She has made five-dollar bets with everyone that she won’t marry before she reaches 23.

The five-dollar bets add up to a small fortune, but Debbie isn’t worried about it because she’s so positive she’ll still be single. Besides, if she is married, her husband will be duty bound to dig in his jeans to pay off. But that’ll be a pleasure for the man who hooks Debbie!

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

(See Debbie’s next MGM picture, Singin’ In The Rain—Ed.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1952