Chance Of A Lifetime

at the sneak preview—they all said Burton

A neighborhood movie house was the scene of a 20th little too quiet to suit the taste of thé nervous producers. Century-Fox preview some months ago. It was what is When the picture was over the audience filed into the known in the trade as a “first sneak,” which means the first opportunity the studio executives have to examine the picture with an unbiased audience. The movie was My Cousin Rachel, and during the screening the house was very quiet. As a matter of fact. you could tell it was obviously a little too quiet to suit the taste of the nervous producers.

When the picture was over the audience filed into the lobby and dutifully walked to the temporary desks provided for the purpose and began filling in the comment cards. There was still little conversation, and none of the usual gayety audiences express at such a screening. When the last of them was gone the producers picked up the cards, took them into the manager’s office and began looking them over. They were almost unanimously complimentary. But something else was much more important, and the studio men were as excited as kids.

On every card there was one name. Burton. Burton. Burton. “More of this man Burton.” “That Richard Burton is something!” “Where has this Richard Burton been?” In their own way, in their own words that theater audience that night made a new star. The studio people were excited because audiences have never been wrong. The movie makers have, but never the audiences. The film went back to the cutting room for minor editing, but the order was out: Don’t cut a foot of Burton!

Subsequent events, such as the casting of Richard Burton in the leading role in The Robe, have proven that the movie industry think he’s the greatest import since Laurence Olivier, and that he is that rare item in British actors, a he-man morsel for American women. A rugged lad with the fire it takes to sweep American girls from their living room chairs right into the movie theaters.

Now something about the man himself, for you will be seeing a good deal of him.

Richard Burton has no traditional background that could qualify him to be an actor. He was born in 1925 in Pont Rhydyfen in the south of Wales, coal mining country. He was one of 13 children, the tot in a household that depended for its bread on the work its men did in the pits and a youngster of 13 is a man in the coal country. From his earliest childhood, Richard Burton was aware of the poverty about him, but his lot was no different from his neighbors’. He knew the pinch of hunger, the dreadful chill of insecurity, but, he says, he never knew unhappiness in his home, or at any time as a child. The Welsh have backbones that stand up under strong adversity—and they know how to smile.

The Burton boys were all sturdy lads, and as tough as they were rugged.

“We lived in the slums, right in the heart of the slums of our town,” Burton says. “My real name is Jenkins, and we were called the Jenks, the scourge of the ‘top end’ of the town. There was an rish family, equally as violent as we, and they were the scourge of the ‘lower end’ of the town. The two families were in a constant feud.

“When I went to school, being the youngest of the Jenks, I had the full protection of my brothers, and not a teacher pared lay a hand on me—although Welsh teachers are known for their corporal punishment of pupils. But even so, I always considered it an insult to be called a Jenks.”

There was actually never any encouragement given the Jenkins boys to let out of the mines and into other lines of work, certainly not into anything cultural. Richard’s father, now a man of 80, had been a miner all his life, and just a couple of years ago. The boys did, however, take off on their own and today they are scattered about the world working at everything from professional football (soccer) to soldiering. Richard is the only one in the theater.

While he was still an infant, Richard Burton’s mother died and he went to we with a sister who was then 22 and married to a coal miner. He remained with her for more than ten years. As he says himself, he was a “rough” boy, and if it hadn’t been for meeting a man by the name of Meredith Jones he might still be so today. Very few boys in Richard’s district spoke English. Welsh was the common tongue in the homes. Jones discovered that Richard had an ear for English and tutored him. Consequently, when it came time to take the entrance examination into what corresponds to our high school (it was in English, of course) Richard passed—and became the first boy from his district in 35 years to do so.

When he was 13 years old, a double crisis came into his life. His sister’s husband came down with an attack of silicosis, the disease which attacks the lungs of miners, and a depression hit South Wales. It became necessary for the boy to go to work, so he became a shop assistant in an establishment dealing in men’s suitings and worked there for almost a year until the family’s financial lot improved.

This breach in his education was in reality something of a Godsend, as it was to prove later, for when he went back to the halls of learning a new teacher had arrived, a man named Phillip Burton, who has had a tremendous influence on Richard’s life ever since. As a matter of fact, when Richard became an actor he took Burton’s name.

“Phillip Burton didn’t see anything in me at first,” Richard says. “I saw something in him. He was an erudite man and seemed to possess all of the qualities I wanted to develop in myself. At that time I wasn’t sure just what I wanted to be. I used to admire the eloquence of the preachers at the churches I attended, and I sometimes’ thought I, too, wanted to be a minister. And then I learned that Burton was a writer and had been an actor, so I went to him one day and told him I wanted to be an actor and asked him to help me.”

The announcement that Richard wanted to be an actor may not have been astonishing to Phillip Burton, but it most certainly was to Richard’s family. In the district he lived actors were considered “sissy” to say the least, and Richard’s brothers could not have been more taken aback.

“I had a vast ego by this time,” Richard says, “and it was somewhat deflated when Phillip Burton informed me there were a number of things against me. There was the district. I’d get no help there, as the natives thought the proposition that people got paid for prancing about on a stage fantastic. I had a tendency toward chubbiness; and I was short at 14. But I was persistent, so eventually he gave me a small part in a school play—and later on a larger part. I imagine I was appalling, but it was a start.”

Phillip Burton must have seen something of the spark that was to hold legitimate theater audiences in London entranced later on, for suddenly he began a strict supervision of the young man’s theatrical activities, having him come to his home a couple of hours each evening for tutoring. He began with a general cultural course of education and then carried on through with speech and the rudiments of stagecraft.

“There were times I thought I’d go mad,” says Richard, “but Burton never let up on me. My Welsh accent was very thick, and he’d take a speech from a play by Shakespeare or Shaw and make me learn to speak it exactly as he did. It was very difficult for me. I’d stand in front of him by the hour repeating after him exactly like a parrot. He was in advanced middle age and tended to be pedantic, and he never once, during the first two years he worked with me, ever said he thought I’d be a good actor.”

At the conclusion of his high school education, at 16, Richard got an opportunity to take an entrance examination for Oxford. It was the turning point in his life, but it seemed certain he would flunk out.

“I could tell you what two and two were,” he says, “but beyond that mathematics were a total mystery to me. That’s when Phillip Burton came to the rescue again. He began to teach me, and one day put his finger on the kink in my mind that made figures difficult. The result was that I breezed through the examination.”

It was while waiting for Oxford that Richard Burton’s big break came. He read an ad in a Cardiff newspaper stating that an actor was needed for a role in an Emlyn Williams play, and he had to speak Welsh. Richard was only 16, but he was aware that there was a shortage of actors due to the war, so he applied for the part and got it.

Although Cardiff was only 14 miles from his home town, young Burton had never been there before he applied for that job. The trip itself was almost the peak of a boy’s career, but when he found himself in the West End of London a few weeks later, rehearsing on a real stage with celebrated performers he thought he was in heaven. That was nothing compared to the notices. The critics were unanimous in their praise of Burton’s talent, all saying, in effect, that he had a “remarkable quality” on the stage.

It is a fantastic thing for a Welsh mining boy to escape the pits, but it is equally odd for any young British actor to escape the years of repertory and make his professional debut in London’s West End. Richard Burton had done both. But at the end of seven months, Richard left the play to go to Oxford. At the time he was earning a slim 30 dollars a week. It may not appear so much to Americans, but it was exactly double what his father was making, after spending 60-odd years in the Welsh coal mines.

When he was 17 years old, with a year of Oxford behind him, Richard Burton became eligible for military service, so he enlisted in the RAF, where he stayed for the duration of the war. He is not much of a military man, so he remained an enlisted man all during his service, a period of three and a half years.

Discharged from the Army, Burton found himself at loose ends, much as many young men of his time did. He had to make up his mind if he wanted to remain on the stage or get into some more stable occupation. The stage won, for a try anyway, so Richard took his last bit of money, went to London, and called on a man named Binkie Beaumont, a producer who had seen him act before the service, and barged into his office like a star come to pick up his script.

“It was pretty funny,” Richard says. “Although he had asked me to look him up, I knew he didn’t remember me. After we had talked a few minutes he excused himself—and I knew when he came back into the room that he had been out looking me up. Well, the result was that that very afternoon they brought in a contract, which I eagerly signed, agreeing to pay me ten pounds a week.”

A lot of experience was crammed into that year, which was the term of the contract. Burton appeared in half a dozen plays and in one movie, which he didn’t particularly enjoy making. And at the end of that time, feeling he had the world by the tail, he went out and applied for a job as a free-lance actor.

“I’ll never forget it,” he says. “It was the first and only time I was ever fired. They said I was too young, but I believe they thought I was incompetent. I am glad to be able to say, though, that the director who fired me has since offered me any number of parts, none of which I have been able to take.”

It was in The Lady’s Not For Burning, a play by Christopher Fry, that Richard Burton first became a real hit, and it was in this play that he made his debut on the American stage in New York. From there on he went great guns. His next job was playing ten months of Shakespeare at Stratford-on-Avon and his reputation was made as far as British audiences were concerned. It was while working at Stratford-on-Avon that Richard got his first big-money movie contract. Alexander Korda came to see him and signed him to a multi-picture deal, which, by the way, Burton is still working out. It calls for a picture a year for five years. It is odd, incidentally, that although Burton has made four of these films none have been made by Korda. He has been loaned to other producers.

Richard Burton is married to a tiny elf of a woman with prematurely greying hair who was formerly named Sybil Williams. They met while he was making his first film, Woman Of Dolwyn. Sybil, still in school, had gotten a job working in the movie during her vacation, and their meeting could reasonably be called love at first sight, for they were married shortly after they met on February 5, 1948. Sybil, too, is Welsh, and was raised in a town just a few miles from Richard’s home, but they never met until they came to London after they had grown up.

Although many miles separate Richard Burton from the Welsh mining town that was his home as a boy, he has never lost touch, and each week he writes a letter to his sister, Cecilia James, who raised him, and she reads it to the rest of the family. He is not in touch with most of his brothers, though, claiming, rightfully, that he’d have to have a mimeograph machine to accomplish this. It is an odd arrangement, this letter writing, because to this day none of the family has ever answered one of Richard’s letters. But they know he’s all right.

Money is not one of the important things in Richard Burton’s life, although his current contract to make The Robe is one of the best in Hollywood.

“I have a respect for money, though,” Richard says, “because I have seen what the lack of it can do to people. My sister, who is only 45, looks 65 . . . all because of the years of poverty, the malnutrition, the constant need and struggle for money. I think it was for her I’ve done all this. I wanted her to have money. But I also wanted to conquer the world and make her proud of me.”

Life in Hollywood is a lot of fun for Richard Burton. He likes America. He likes people. He likes fast cars and the free and easy way of life. He spends a good deal of his time in the company of other British actors, the James Masons, the Grangers and Robert Newton—but he is making American friends fast. He is a rather shy man until you get to know him, but he warms to people and he appears to be the kind of man who once a friend will remain a friend always.

Off-screen his appearance is vital. His head is large, covered with a shock of dark brown hair, worn long for his role in The Robe. His eyes are intense and probing, and the other features masculine and rather classic. The marks of some childhood pox are on his skin, and he enjoys referring to them as a mark of ugliness. His humor is quick and earthy, and he likes to drift into the male jokes of his boyhood, told in the vernacular of a Welsh brat. He’s not a tall man, probably slightly under six feet, but he gives the impression of massive strength when he enters a room. He is, in truth, a splendid figure both on-screen and off.

As he looks back on the strange story that is his own life, Richard Burton would change few things. Life was hard in Pont Rhydyfen, but it was never without love and a laugh. The rowdy character of his formative days made him a man able to cope with any problem of his manhood. He carries in his heart a great respect and gratitude for Phillip Burton, who, by his interest and hard work, saved the youngest of the Jenks from the pits. He is eager to use the knowledge he struggled to come by so his enthusiasm is boundless. His mind is filled with memories of the boosts given him, so he is a man other actors will find ready to give them a leg up when needed.

All of these things are seen in the man’s personality and in his work. Richard Burton is indeed a star who will add to the quality of American movies.

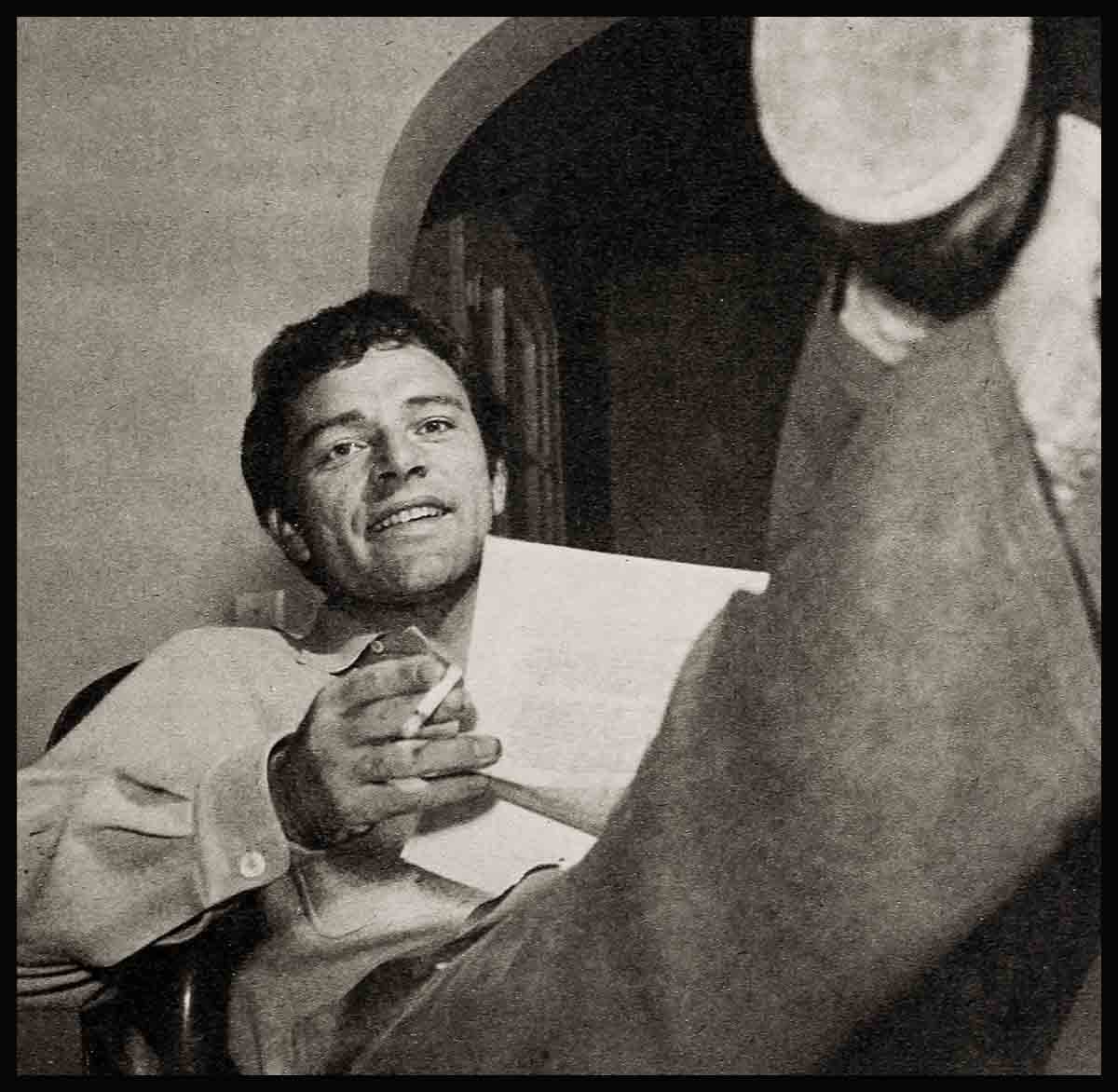

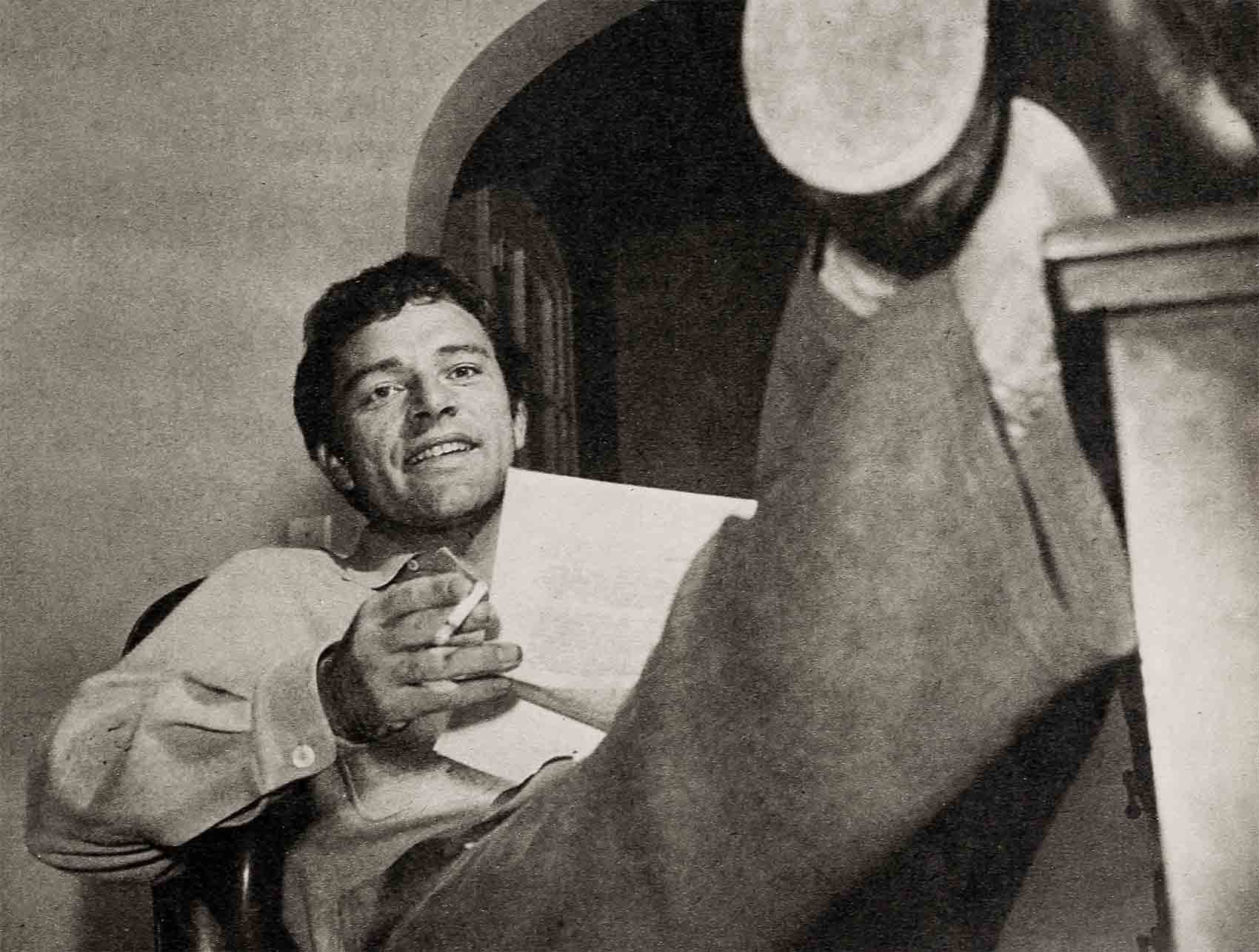

a press agent’s brain-storm came true

Keefe Brasselle was pretty blue the day he dropped by the office of his old friend, the publicist, Glenn Rose. He wasn’t getting parts; he feared his option would be dropped. As he recited his miseries, Glenn suddenly pointed a finger at Keefe. “You are going to be Eddie Cantor.” Keefe told him he’d lost his mind. “I don’t look like Cantor; too many other actors are after the part.” But Glenn’s eyes were glazed with an idea that wouldn’t let go. Keefe went home. Glenn grabbed a phone to tell Sidney Skolsky to stop worrying about a lead for The Cantor Story. Meantime the idea began to bother Brasselie. He had some pictures of himself made up to look like Eddie. Glenn hunted up a girl named Barbara Donahue, who worked for an optical company. Contact lenses were needed to change his blue eyes to dark Cantor color. He called Keefe and announced, “Boy, I got your eyes—for nothing.” Then they button-holed producer Skolsky in the back room at Schwab’s drug store. Miraculously, Brasselle had the part of his life. This is the true story of how one man’s idea secured the future of a star. The talented boy from Elyria, Ohio, who clerked in a Hollywood shoe store, and sold automobiles to support his family—Keefe Brasselle—has clicked for good!

talent scouts watch television

It just seems that every time Anna Maria Alberghetti opens her pretty mouth to sing, she gets moved. It happened on her home Island of Rhodes, before she was 12. She had concert engagements in Italy, and won passports for herself and her war-exhausted family when she sang her lucky song, “Cara Nome” for the military governor. A high C in Italy won her contracts in America at Carnegie Hall. One trill in that famous auditorium and music-devotee and celebrated MC, Ed Sullivan had her on his TV program. The camera had just focused on her golden throat when she was spotted by Adolph Zukor. She was whisked from New York to Hollywood to sing in a picture with another tune-hummer, Mr. H. L.. Crosby. To complete this fairy tale that came true, Anna Maria got a contract at Paramount. In The Stars Are Singing, Miss Alberghetti proved she could act as well as sing. She’ll be teamed with Rosemary Clooney again in her next, Red Garters. She never sings a note before 12:00 noon. Her father, a fine musician and her teacher, says because she is so young, not yet 16, it would harm her voice to sing before her body is fully awake. Once having heard her, nobody, not evert the neighbors, can wait till she’s old enough to sing all the time, from morning to night.

all it took was a pair of scissors

Joanne Gilbert is as flabbergasted as anyone else over her amazing leap from obscurity to movie fame without having appeared in a single picture. This newcomer, who’s set to star with Donald O’Connor in The Big Song And Dance says, “I’ve had nothing but luck!” Part of that luck is the fact that although her parents are separated, her mother sensibly allowed her to see a lot of her dad, Ray Gilbert, Academy Award winning song writer. One day, tired of her 5-year career of modeling, Joanne told him, “I’ve got an idea. Would you write me some special material?” “Sure,” he replied. He wrote. She sang. He listened. His eyes popped wide open. Then Joe Pasternak of MGM suggested she put on a charity performance at the Mocambo. Owner Charley Morrison was enthusiastic until she showed up in a man’s white blouse and long black trousers. All was saved, however, when someone in a fit of genius produced a pair of scissors, snipped away the pants legs and behold! There were legs that would make Marlene Dietrich think twice. The results were startling. The sultry, emotion-filled voice, the big hazel eyes knocked Hollywood for a loop and Paramount for a contract. One critic said, “That voice—those eyes—the legs that never stop. WOW!” And Hollywood thinks fans will agree.

who’s the tow-head in the tenth row?

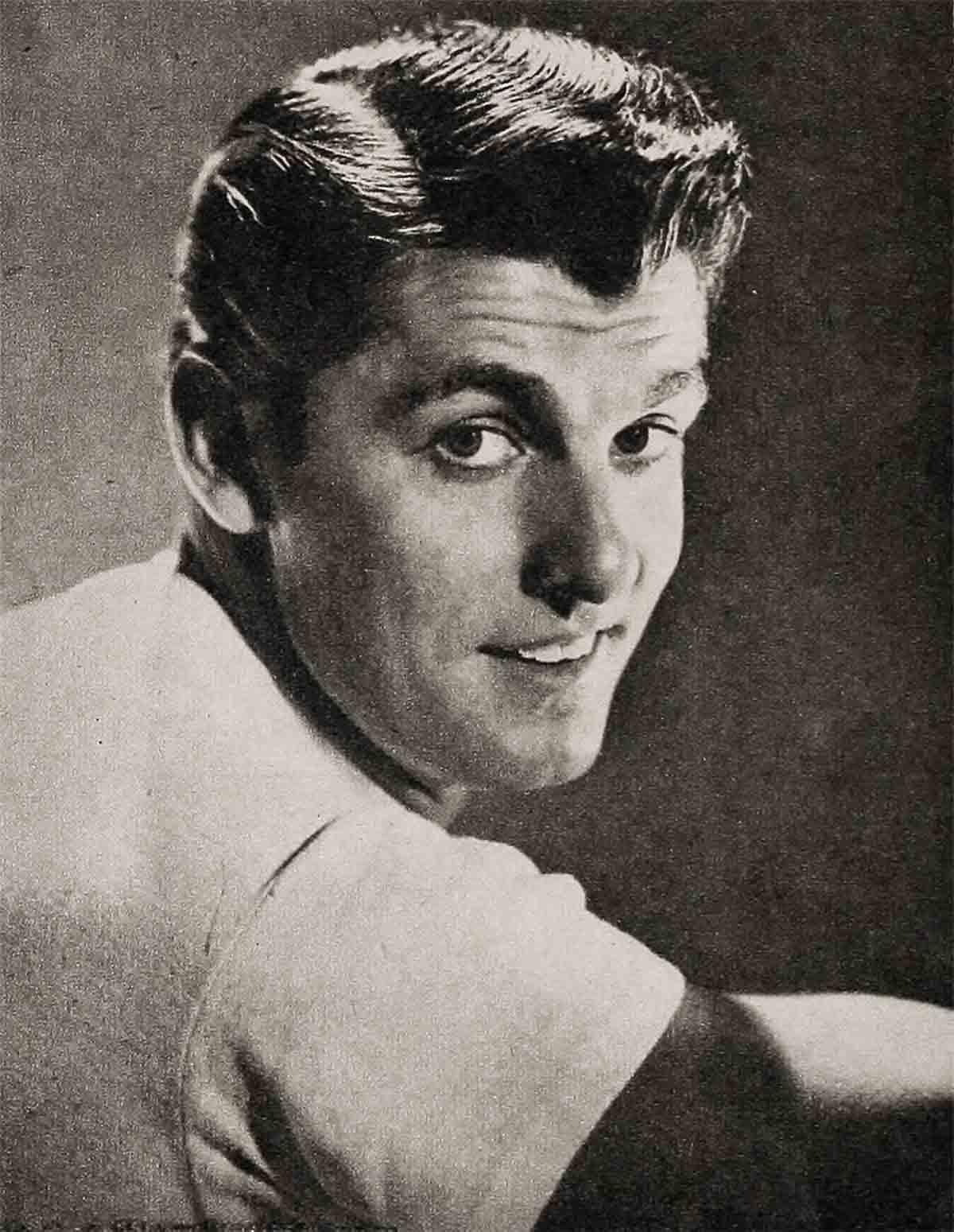

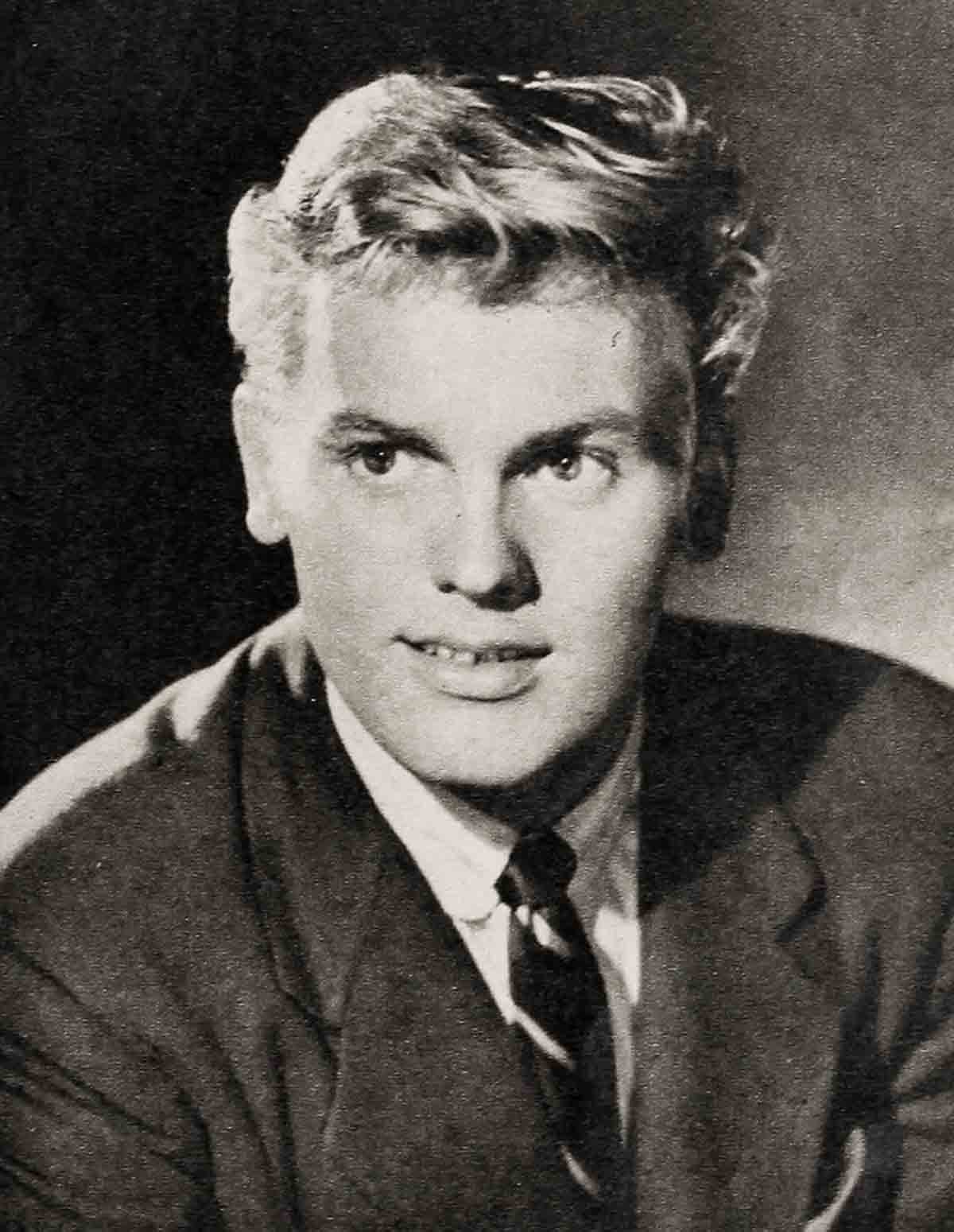

Tab Hunter is a lad who never bled to be an actor. Asa matter of fact, he was plucked off the bleachers at an ice-show, and thrown into the arms of Linda Darnell. He was a spectator at an ice show the night Henry Willson, a top talent scout, spotted him all a’gog at the figure eights. Willson has picked people like Linda Darnell, Rory Calhoun, and Lana Turner before they knew the front end of a camera from the back, and helped them develop into stars. He wanted the same thing for Tab. And Tab didn’t mind a bit. His first role was in Island of Desire, with Miss Darnell. Now he’s slated for Steel Lady. Tab is the boy-next-door type, an ex-San Franciscan who doesn’t believe that his profile is heaven’s gift to movies. He works hard to keep in trim, riding and jumping horses; studies acting and singing diligently. He lives with his mother, but call him “Mama’s Boy” and you’ll collect a good sock on the nose. At 22, he’s a bachelor and an ex-Marine. He ran away from home at 15 to join the Leathernecks. Now that he’s home again the situation is still well in hand—including the social life of Hollywood. This boy gets around with the best—Susan Zanuck and Debbie Reynolds, for instance—and Hollywood predicts that Tab Hunter will stay around for a long, long time.

Tomorrow’s spotlight will shine on these new faces—17 youngsters hand-picked and ready for the big break.

ELAINE STEWART and Marilyn Monroe have something in common: Marilyn was married to a policeman, Elaine is the daughter of one. Something else, too—of all the girls in Hollywood, Elaine is Marilyn’s closest sex-appeal competitor. She’s in Young Bess

RICHARD ALLAN majored in music at college till World War II came along. Drafted, he ended up in an overseas laundry unit. His first film break came when he doubled for Monty Clift’s swimming scenes in Place In The Sun. His latest (same old water!) is Niagara.

PHYLLIS KIRK has been given a fast shuffle by Hollywood . . . but it looks like the time has come for a “new deal” for her, now. Under contract for a while, first to MGM then to Warner Bros., at last Paramount gave her a break in their Iron Mistress.

PALMER LEE’s been called everything under the sun by casting agents: too short, too tall, too handsome, too ugly. But, like the patient NorwegianAmerican that he is, he stuck it out till U. I. took a second look and signed him up. His next: The Cimarron Kid.

KATY JURADO used to be such a tomboy she beat up all the boys in the neighborhood. She still floors ’em, but with her flashing dark eyes, now, instead of her fists. A native of Mexico, where she was a top star, she made a name for herself here in High Noon.

TOM MORTON’s one chorus boy who made good. (Van Johnson’s another.) Tom had the audacity to hire a press agent while still in the chorus. Paramount teamed him with another unknown (Rosemary Clooney) in The Stars Are Singing; has big plans for him.

LORI NELSON had to give up Hollywood at the age of eight. Rheumatic fever cost her a job in King’s Row. But she lived in the movie neighborhood, and pretty soon the gal down the street was on the screen in the Ma and Pa Kettle series. At 20, Lori’s on her way.

KEITH ANDES’ best breaks have come with a germ. He met his beautiful. nurse wife while sick-a-bed. Alfred Drake’s illness in Kiss Me Kate gave Keith a chance to sing the lead 22 times. RKO scouts heard him, cast him in Clash By Night and Split Second.

SUSAN CABOT was born in Boston and raised in the Bronx. She’s as American as a hot dog—but, oddly enough, until she was teamed recently with Audie Murphy in Roughshod, she played nothing but native girls and Indian princesses in her movie roles.

TOUCH CONNORS has been shooting for a screen career right along, but he’s studying law on the side . . . just in case! He is registered under his real name, Joy O’Hanian, at Southwestern University. But, if his role in Sudden Fear means anything, he’ll forget law.

BETTA ST. JOHN licked a serious speech impediment and went on to become a child actress at the age of eight. At 16, she danced herself into the chorus of Carousel on Broadway; next, she landed a job in South Pacific. You’ll be seeing her in 20th’s The Robe.

BYRON PALMER’s performance in Tonight We Sing netted him such glowing notices that Darryl Zanuck signed him to a contract when studios were dropping, not hiring, actors. If “By,” as his friends call him, ever tires of movies, he’ll try newspaper work.

ROBERTA HAYNES’ father used to be an electrical engineer . . . so maybe that accounts for the sparks that start flying when she’s on screen! Her first bit role, in High Noon, wound up on ‘the cutting room floor, but she made out better in Return To Paradise.

CRAIG HILL’s big ambition is to buy a boat that will carry him away on a cruise to South America someday. If his screen career keeps zooming the way it’s doing, he’ll have the money for the trip in short order . . . but no time! He’ll be too busy making movies.

POLLY BERGEN is about as different as you can get. She dances with a Southern accent; attended 45 different high schools; once got fired as a singer because she was “too sexy.” She’s. still something special as a wife to Jerome Courtland—and a star in The Stooge.

HUGH O’BRIAN was the youngest drill sergeant in the history of the Marine Corps. Except for some amateur magic, his aptitude for acting seemed almost non-existant. But Hugh looks good, talks sense, and comes across the screen big in The Man From The Alamo.

AUDREY DALTON hails from Dublin, where she was schooled at the Convent of the Sacred Heart. She has more poise than the average 18-year-old, sparkling blue-green Irish eyes, and a smouldering temper she’s never used. She’s in Paramount’s Pleasure Island.

THE END

—BY KEEFE BRASSELLE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

No Comments