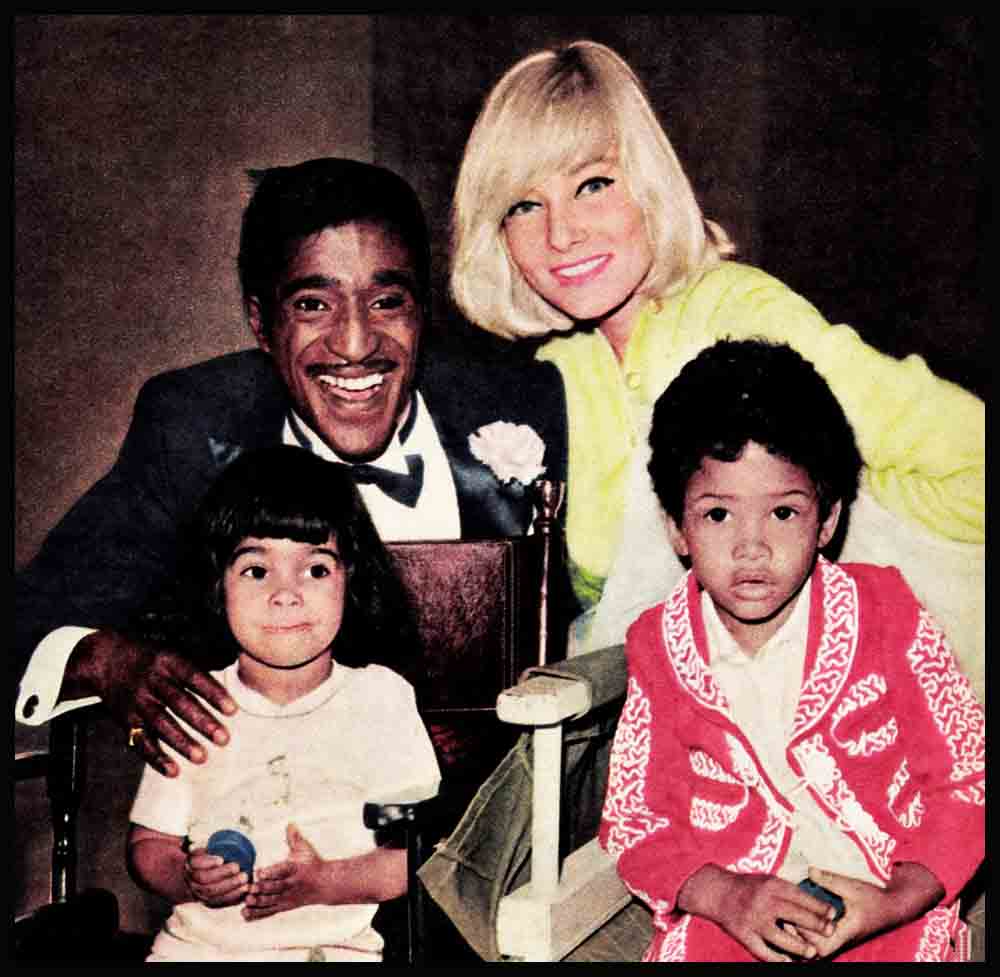

Why Is Mommy White?

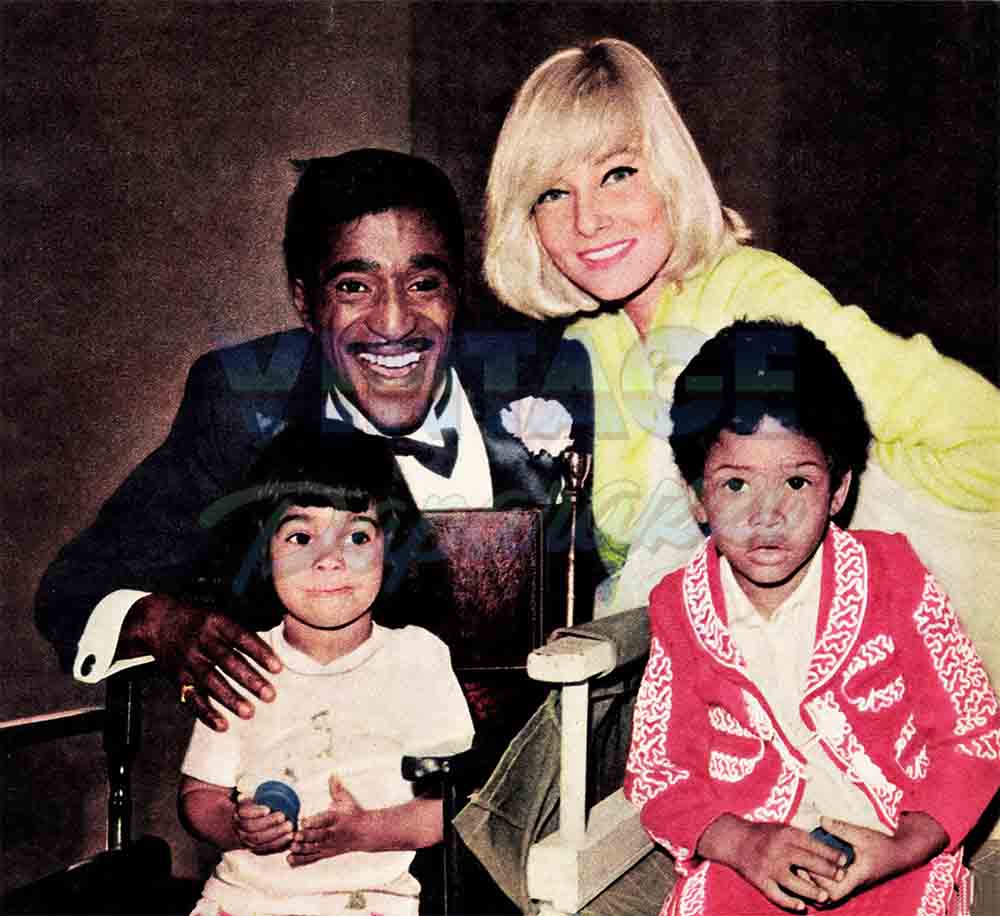

Sammy Davis, Jr., and I had been discussing the special and formidable problems which his children, Mark and Tracy, will have to face as they grow older; they are Jewish; Mark is an adopted child; their dad’s in show business and must often be away from home, separated from them. And their mother is white, while their father is a Negro. To personalize and dramatize the last of these problems, I threw Sammy a fast curve: “What’s going to happen a few years from now when Mark comes home from school one afternoon and asks you, ‘Daddy, why is Mommy white?’ ”

Sammy smiled and said, “Sure he’ll ask. I, wish that was the toughest question he’ll ever ask me. He can see already— and Tracy can see it, too—that May is white and I’m black, so that’s no shock. As to why she’s white—there is only one answer, and any child can understand it: God made her white just as He made me black. That’s what I’ll tell Mark. Once May told a reporter—just after she gave birth to Tracy—‘God must approve of our love or he wouldn’t have given us such a beautiful baby.’ That’s my feeling exactly. And remember, He also gave us Mark.”

“Okay,” I agreed. “But what if Mark asks you, ‘Why aren’t other people like us? They’re all white or all black, but not mixed. And how come you married Mommy?’ What’ll you say?”

“Four words’ll do it,” Sammy replied. “ ‘We fell in love!’ ”

“A kind of simplified version of a statement you made a few days before the wedding,” I reminded him.

Again Sammy smiled as we both remembered the way he expressed himself then to a persistent reporter: “I am not marrying May Britt because she is white. I am marrying May because she has more courage, more dignity, more understanding than any woman I have ever known. We are to be husband and wife because we love each other. . . . May is my happiness and my hope on earth.”

Now Sammy added, “Not only will I tell Tracy and Mark, ‘We fell in love,’ but I’ll also be able to ask them a question and know the answer in advance: ‘Do you know any parents on our block who love each other more than we do?’ ”

“But what if Mark comes home and tells you the kids just called him a . . . a . . .”

“A nigger.” Sammy supplied the word gently. I was grateful to him.

“Yes,” I said, “What’ll you do?’”

Sammy wasn’t smiling now. “I don’t know what I’d do. Exactly. That’s some- thing I’ll only know when I come to it.” He clenched one fist and then let his hand open slowly. “They’ll be hurt. I know it. Tracy will get her nose skinned and Mark—he’ll have his share of black eyes. But when the time comes and they’re hurt with fists or words, God sometimes gives a parent the wisdom—I might find the wisdom and come up with the right answer.

“Every Negro child will someday or other be called a nigger. Just as an Italian will be called a wop or dago, a Jew will be called a kike, a Spaniard a spick, a Pole a polack, a Hungarian a hunky, and so on down the line. Maybe it’s part of our heritage. And if by some miracle Mark isn’t called a nigger, it will be because other parents—not May and me—will make sure that such a word never comes out of their children’s mouths.

“May and I know,” say s Sammy, “that little Mark will ask us that question one of these days. And when he does, our answer is ready. It’s an answer any child can understand because it is filled with love—and with truth.”

“But even well-intentioned parents can’t ride herd on their kids all the time. Like recently I was at a friend’s house—a cat I’ve known for years, a nice guy—and we were just sitting down to dinner when his young son walks in, looks at me and says, ‘Daddy, is that a nigger?’ Well, his father yelled to me, ‘I never said that word!’ and the kid’s mother was hysterical, and the boy just stood there, not knowing what the commotion was about. The point is that he’d gotten the word, the poison, someplace else and he didn’t even know it was lethal. The whole thing bothered his parents more than it bothered me.”

“But the first time,” I said, “the very first time Mark hears the word ‘nigger’ and knows its something mean and bad— that will be an awful day for him—and for May and you. . . .”

“And I won’t have any magic explanation,” Sammy said. “It’ll have to happen along the way—the building up of an anti- dote to that kind of poison. Not overnight, but in slow, steady stages along the way. After all, both kids aren’t even five yet.

“May and I can’t solve the problem of bigotry. But what we can do is to try to bring them up with understanding and patience. We have extras going for us—they’ll be able to go to good schools; they’ll see love all around them in their own house; they’ll have security in the religious faith that we’ve chosen.

“We trust in God. Both my wife and I decided long before Tracy was born that we’d raise our children in the Jewish faith. It’s my faith; it’s May’s faith, although I never asked her to convert—it was all her idea. When Friday night comes, whether Fm there or I’m away, the candles are lit and we hold Services. They gain strength from the fact they’re Jewish. When Hanukkah comes, we go all out to celebrate the holiday.

“Tracy was named in the temple; Mark hasn’t been named there yet, but he will be, once the waiting period after his adoption is over.”

“Will you tell Mark he’s an adopted child?” I asked.

“Of course. He knows we love him. So it will be easy to tell him he’s adopted. Look, the key thing is to be honest. Completely honest with kids. Tracy and Mark are used to asking questions and they’re used to getting straight answers. Because we don’t duck or fudge, they trust us.

The truth always

“l’m not Dr. Spock. And I’m certainly not Martin Luther King. But I know that a child can stand one-hundred per cent, absolute honesty, better than an adult. What does a kid really want to know, no matter what questions he asks? Does Daddy love me? Does Mommy love me? Can I get that toy? That’s it. If you’re honest, you have their complete confidence and respect.

“So I’ll tell Mark he’s adopted. And I’ll tell both children they’re Jewish and help them to live their religion. And I’ll let them know their mother was a Swede, but that she’s now an American Citizen, and that I’m an American Negro.

“But what is more important, we’ll show them they have love; and they’ll know they won’t have to endure poverty. Rather than being strikes against them, their being Jewish and the children of a mixed marriage and Negroes—and Mark’s being adopted—will be strikes for them.

“We’ll tell them: ‘There’s no need for you to grovel in the dirt. We’ll back you up. We need you.’ ”

I said, “That certainly should help protect them in the years ahead.”

“Protect them, but not save them,” Sam- my said. “I still don’t know what I’ll do, what I’ll say, when Mark or Tracy comes home and tells me one of the other kids said, ‘You’re a lousy nigger’ or ‘You’re a dirty Jew.’ No parent can honestly say what he’ll do. But if adults leave kids alone, they’re not prejudiced. Prejudice is instilled by adults; it’s picked up from adults. Problems there’ll always be. But what white Protestant with lots of money has a guarantee against problems?”

“Right now, though, this kind of problem hasn’t hit Tracy or Mark yet?” I asked.

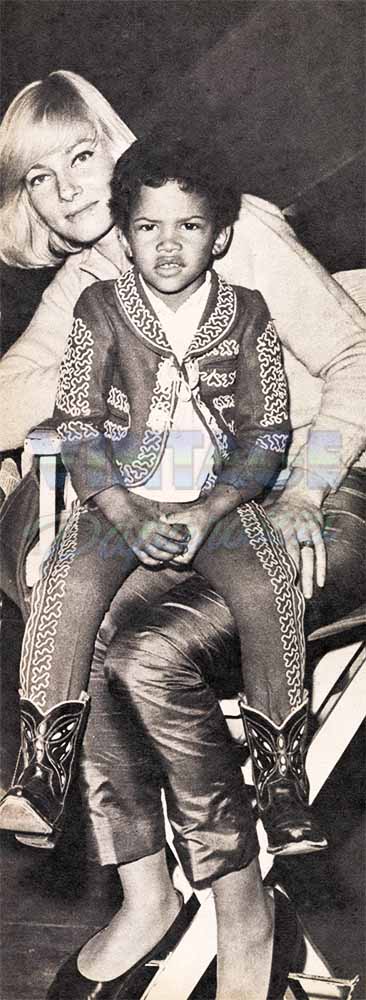

“Thank God, no. My kids are too young. They go to nursery school, they’re with all kinds of children. I don’t want Tracy and Mark to live in an all-white world or an all-black world.

“There are five kids in our immediate neighborhood. My children are as happy as any. They go to nursery school, they play, they have parties. But what really makes them happy is the fact that May and I love each other and it shows. If they saw disagreements and fights, then they’d have trouble.

“Let me tell you something: the children of mixed marriages usually get love and understanding beyond the usual, because the parents of such kids have had to realize a greater love and understanding in the first place.”

“Has the press—newspapers and magazines—given you and May the understanding you want?” I asked.

Sammy grinned and ran his hand through his hair. “If anything the press has been too good to me,” he said. “Somehow I’ve survived even though I’ve gone ninety per cent against the stream. And I’ve got a great deal of help from the press. Honestly, I thought they’d be against me. But when I announced I was going to marry May, the reporters and writers said, ‘Let’s give ’em an even start for openers. If he steps out of line, jump on him.’

“Now, I know that even though they were being fair, a lot of guys were convinced that I could never make it from being a wild bachelor to being a married man. Well, recently one of these guys went out of his way to tell me, ‘I never thought it would work, but you’ve done it.’ ”

“All sweetness and light from the press all along?” I asked.

“No. I think one guy got a little out of line after Tracy was born when he asked me, ‘What’s the color of the baby?’

A rough world

“Later, at a press conference, one re- porter threw a fast ball at me by asking, ‘What ya gonna tell your daughter about mixed marriages?’ I told him the question was tough, but that it was going to be even tougher than that to tell her about the atomic bomb and to teach her to love in a world that seemed cruel and chaotic.”

I looked down at my notes and then asked. “What about the charge that you and May and the kids were going to run away from America and become British citizens?”

Sammy shook his head. “What I did say—that’s when ‘Golden Boy’ was scheduled to open in London, which has been changed—was that I’d like to live six months in London and six months in the United States, and that I was interested in buying a home there. The English have wonderful manners. Kids say, ‘Sir,’ to an adult man. I thought it would be wonderful if Tracy and Mark learned such manners. But wishing that I could live six months in one country and six months in another isn’t the same as deserting one’s own country. May and I love America. It’s been good to both of us.”

Again I checked my notes. “Along the same line, what about the accusation made against you by some people that you’re playing it safe on the integration issue? At a Los Angeles rally for Martin Luther King, for instance, you were quoted as saying, ‘This should prove once and for all, your leader is my leader.’ Some people interpreted that to mean that you were defending yourself against the charge that you hadn’t stood up and been counted in the fight against racial discrimination.”

Sammy laughed bitterly. “Boy, some people love to make a mountain out of a molehill. I was making a joke, but I guess some refused to get it. You know, in my act sometimes I kid around about my good friend Frank Sinatra and I say, ‘Frank Sinatra is my leader.’ It’s a line most people who catch my shows have learned to expect. Well, when I said what I said about Martin Luther King at the rally, I was kidding myself—my own line about Frank, but I was also telling the truth—that I was in the integration fight all the way.”

I put my notes back into my briefcase, smiled and said, “Okay, the record stands corrected: You didn’t try to run away from America, Sammy, and you didn’t try to run out on the integration struggle.”

Sammy leaned forward. “Look, I couldn’t step out of my skin even if I wanted to, and I don’t want to. Every guy must fight the best way he can. For himself, for his family, for people every- where.

“A guy in the office typing reports appreciates what the guy in the front line is doing. He respects the front line fighter, but there has to be some cat back home to give in another way. I like to think, for instance, that the $70,000 I helped raise at a California benefit, recently, makes it possible for those guys on the fighting line against discrimination to do the work that must be done.”

I fumbled in my briefcase again and came up with a clipping that told how the Rev. Martin Luther King had been assaulted in Birmingham when he announced from a platform there that Sammy Davis, Jr., would give a benefit performance in White Plains, N. Y. for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. I read aloud from the news clipping: The attacker “asserted that Dr. King stood for ‘race mixing,’ and denounced Mr. Davis for having married a white woman, May Britt, an actress.”

Sammy interrupted me. “That’s what I mean when I say every guy must fight the best way he can. I’d defeat the whole movement if I fought in the front lines. I’m too vulnerable. I give the bigots too many weapons. They’d all say, ‘Ya see what happens when we don’t ride herd on Negroes? A colored fellow immediately marries a white gal.’ It would be silly then to answer that my marrying May had nothing to do with the integration struggle, that it’s strictly a personal matter between a man and a woman. They wouldn’t even listen to that.”

“What about the March on Washington?” I asked. “I didn’t see your pictures in any of the papers. I don’t know, were you there?”

“I was there,” said Sammy proudly. “But I wasn’t part of the Hollywood contingent, if that’s what you mean. Don’t get me wrong. I believe that eighty per cent of the Hollywood contingent were sincere and honest—guys like Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Jimmy Garner, Burt Lancaster and Charlton Heston and many others. But where was that other twenty per cent ten years ago? Where did they come from all of a sudden—beating their breasts proclaiming, ‘Hey! I’m liberal?”

Sammy pointed to the wall of his dressing room on which hung a large photograph of Martin Luther King addressing the rally. “I took that picture,” he said. “It was a glorious day. Marvelous. Glorious. I flew from Detroit, where I had a club date, to Washington to be there, and then I flew back to Detroit.

“In the middle of the whole thing I just had to slip away to the phone and call May to tell her all about it. I just had to share my feelings with her. I remember telling her, ‘I’m so glad I came, so glad I’m here.’ For so many reasons. So many, many reasons. But the main one, I think, is that when years from now Tracy and Mark ask. ‘Where were you during the March on Washington?’ I can answer, ‘I was there.’ ”

I looked down at the floor and then up at Sammy. “I’m sorry, but I have to ask you this: Where were you ten years ago?”

Sammy said, “Doing the same thing I’m doing now. In 1954 I was doing benefits for the NAACP. I’ve been a life member a long, long time.”

“So you took photographs in Washington instead of having pictures taken of you?”

“That’s right,” Sammy replied. “I asked the news boys not to snap my picture and they didn’t. A guy from NBC-TV asked me to say something into the cameras. I said, ‘No. No publicity.’ Then the guy said, ‘We’d like you to be on with Roy Wilkins.’ I was so flattered I said yes. Just that one exception. So there we were, Mr. Wilkins and I. Not as the leader of the integration movement and an entertainer, but as two American Negroes who were pleased and proud and overwhelmed at what had happened.

“Later, when some cats I knew asked me, ‘Why weren’t you there? We saw the pictures of other stars in the papers and caught them on TV during the first part of the Washington ceremonies. Where were you?’ I didn’t say a word. I knew I was there; May knew I was there; the kids will know I was there. That’s all that’s important.”

For a moment we were silent, both looking at the pictures on Sammy’s wall. Of the March . . . of his kids . . . of May. Then I asked, “What happens next? For you and your family. What plans?”

As Sammy answered me, he still gazed at the photographs. “Next for me—for us—is ‘Golden Boy’—on Broadway. We open at the Majestic in late September. I hope that means the whole family can be in New York for a couple of years. We’ve rented an apartment in the Sixties, off Fifth Avenue. I figure we can run a year or a year-and-a-half at least. With any luck, two or three years.

Kids—all kinds of kids

“It’ll be a sit-down period. A chance to see our kids grow. We’ve enrolled them in The Little Red Schoolhouse. There they’ll be exposed to kids of all colors, religions and social backgrounds. That’s important—that my kids will meet the children of laborers as well as those of doctors and lawyers.

“This is how it should be. Worse than letting kids run loose is to overprotect them. To make everything so smooth and easy that they’ll crack when the first little problem comes their way. Parents who try to overprotect their kids are silly. Boy, if we ever get in that bind, we’ll be in trouble. The kids will resent us. And we’ll be making them miss all the joy of meeting and licking obstacles.

“I know what I’m talking about. In a crazy, reverse way, I was overprotected. By show business. I was so busy from such an early age that I never had time to do what other kids do. I can’t roller skate. I never played baseball. Sure, now I play golf; but I’ll tell you a secret, I picked golf because it’s a one-man game and I can be bad at it without others knowing how bad I am. I was just too busy to be a kid—one-a-day shows, two-a-day, shows, three-a-day shows.

“So I want my kids to experience everything. To make their own mistakes and know that May and I are there to catch them when they fail.”

I started to get up, but sat down again when Sammy raised his hand and said, “Please do me a favor. Write down something especially for me. Please let people know that I’m aware that every white person, South and North, isn’t a bigot, and that every colored person isn’t a hater. May and I couldn’t have married, couldn’t have wanted to stay in the United States the rest of our lives, couldn’t have decided to raise Mark and Tracy here if it hadn’t been for the way most Americans said, ‘Give them a chance. Let’s see.’

“The problem today is not being Negro or White, Gentile or Jew. The problem is to be human—for a parent to raise his children to respect God, society and his fellow man.”

—J. Albert Smith

Sammy’s in “Three Penny Opera,” Embassy, and “Robin and the 7 Hoods,” for Warner Brothers. His next is “The Major and the Private,” for Embassy.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1964