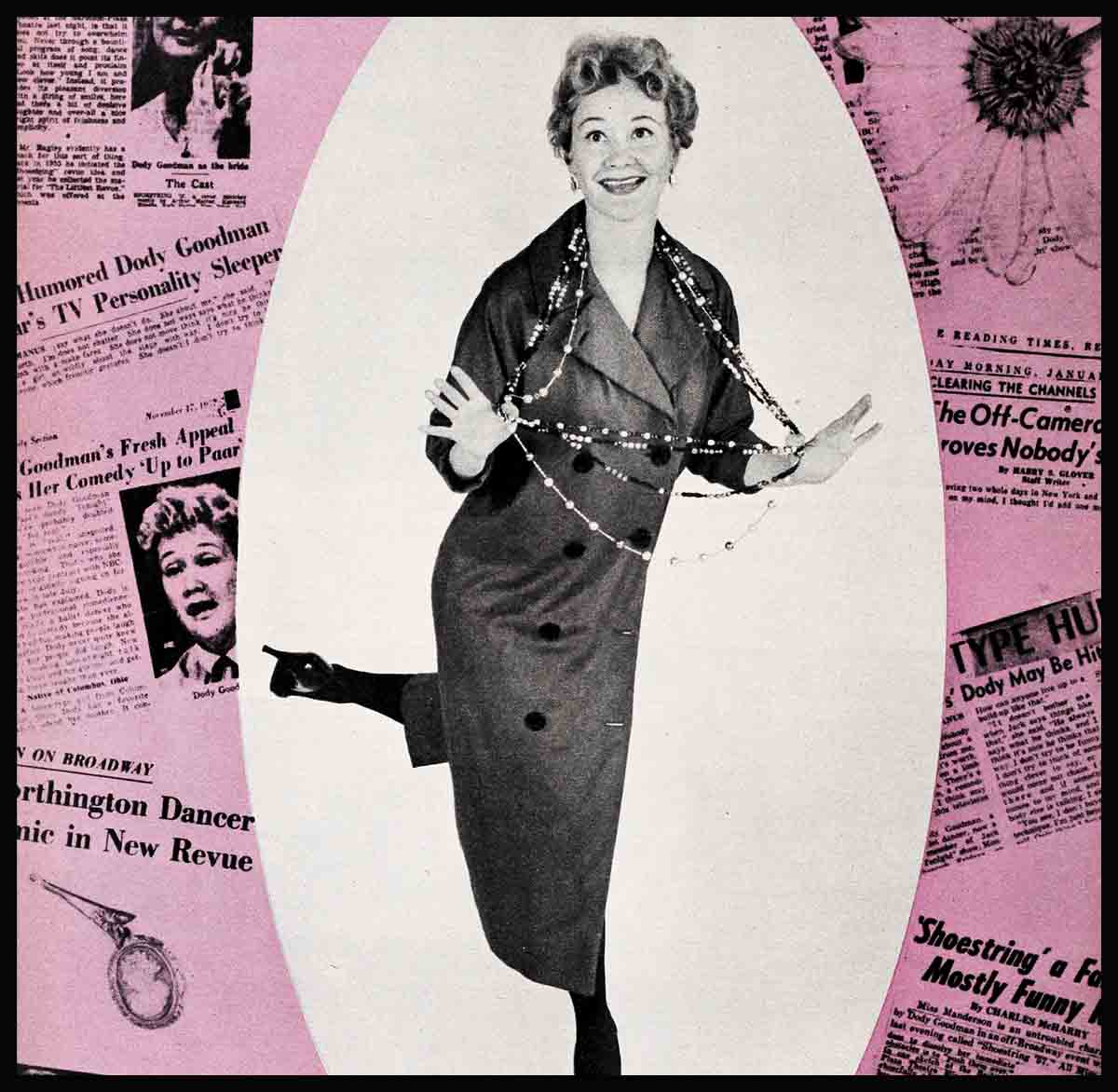

Dody Goodman: “I’m For Real I Think”

When people started asking, “Is Dody Goodman for real ?”—well, I didn’t know what to make of it! Nobody’d ever asked that before I was on the Jack Paar show.

I usually say, “Well, as far as I know I’m for real.” But I can tell people never seem satisfied. Just when I’ve forgotten about it, they ask me again.

My mother read some newspaper stories and she called me all the way from Columbus, Ohio: “Dody, why do they keep asking are you for real? What are you doing down there in New York?”

And I said, “I’m acting just like always.”

I can remember when we used to live on Summit Street in Columbus, there was this other family of Goodmans in town, and one day somebody phoned them by mistake and they said, “Oh no—you don’t want us. You mean the crazy Goodmans up on Summit Street.”

Well, maybe not my father so much, he’s pretty practical. But all the rest of us—my mother, sister, brother, grandpa and me—we never, you know, conformed to any sort of set pattern. Like—well, my parents have always gotten up real early, like around five or six while it’s still dark, and one time Mama heard—well, a noise across the street is what it was, and she looked at the clock and she said, “Oh heavens, it’s so late—you know that, uh, those people across the street are going to work already and we’re still sleeping.”

So she got up and she woke the baby up, my little nephew Johnny, she got him up and washed and down in the kitchen, and she got my father up and she started fixing breakfast. She stirred up a big batch of pancakes, and my father came down and they were all eating pancakes, and little Johnny was—he couldn’t wake up good, and he was sort of crying, and she was stuffing pancakes in his mouth, and my father just happened to look at his watch, and he said, “Is that right? My watch must have stopped. It’s only one o’clock.”

And Mama said, “Oh, it must have stopped.” So they investigated thoroughly and it was only one o’clock. They’d only been in bed a couple of hours, and the people across the street were just coming home from a party. See, what it was—she looked at the clock wrong. It probably said 12:30 and she thought it said 6:00.

Some of the critics have referred to my humor as sort of vague and scatter-brained. So—well, I don’t deny it but I sure come honestly by it. Like once when I was seventeen I did a split—on a dare—right in the lobby of a big hotel. It was—well, it’s called the Deshler-Hilton now. When my mother heard about it, all she said was, “What! In that new evening dress!”

Papa always said we were spoiled, and I guess maybe we were. Like nobody did a thing to my brother Dexter when he smashed up the family car. It wasn’t his fault, but you’d have thought they’d have said, “For goodness sakes, watch it,” or something. I suppose it explains some of the other things he’s done, too, like taking a taxi all the way from Indianapolis to Columbus (around 175 miles, I think), when he got discharged from the Army. And my sister Rose eloped twice.

And as for Mama—well, she gave a party for me about a year ago when I was home on vacation and she was so excited she hardly saw anybody! She was going around madly introducing herself to everybody, and she went up to this young man and she said, “How do you do. I’m Dody’s mother.”

And he said, “Yes, I know. I’m her brother.” Sure enough, it was Dexter. See what I mean? I mean nobody in their right minds would think of us as an average family. But we always had fun.

Papa—his name is Dexter like my brother’s—was an executive with Gallagher’s Cigar Manufacturing Company in Columbus, and for most of our lives we lived in this two-story—well—white frame house is what it was. We had front porches, and we had a big hedge that went around the house and we had, well, rather a large back yard with grass, when we didn’t ruin it playing with the hose in the summer. We had a sand pile out by the garage, and a playhouse that we loved to paint.

We had this big collie, Lady, who lived to be about thirteen years old. And a cat. And I can’t remember the cat’s name, but she used to have to take all her meals on top of the refrigerator because otherwise the dog would chase her from one end of the house to the other. And while the dog was chasing the cat, like as not the neighbor kids and I would be in the living room banging on my sister’s piano, or trying to lift my brother’s bar bells, which shouldn’t have been downstairs anyway. I remember I used to love to play red light, hopscotch, statues and jacks. And I was forever dashing in and out making peanut butter sandwiches and yelling at my brother, who loved to hook the latch on the screen door so I couldn’t get in.

The other girls on the block were always more—well, you know—pretty little ladylike creatures in short socks, while I wore long stockings over this long lumpy underwear. I hated that! I don’t know that I was a tomboy exactly—I guess not really, because I loved dolls—but I thought nothing of fighting with the boys, and I could defend myself pretty good. Then I’d have these moods of wanting to dress up in high heels and swishing around pretending I was—oh, maybe Joan Crawford or somebody else just as—you know—glamorous.

I’m not sure, but I think I was about eight when Mama sent me to the Jorg Fasting ballet school. And—uh—by the time I was twelve I was a pretty good dancer and I guess that’s when part of me got real serious. I could always, you know, picture myself as a great ballerina. Maybe I was what they call a split personality, because part of me was trying to be a comedienne, too. Even in grammar school. I seemed to always be doing crazy things to get a laugh like, oh, falling out of my seat or maybe imitating the teacher behind her back.

My grades were about average, I guess. Except, you know, when I wanted to apply myself. Like when I was on the student council in junior high and made the honor roll. I always got along well with other children out of school, but I think in school what I suffered mostly from was being shy. It was hard for me to get up in class and recite. When I could make the kids laugh it was fine, but I was very self-conscious if I had to be serious. And if I would be corrected in public or anything like that I would get terribly embarrassed and act awful. I’d yell at my parents and then—oh—I felt just terrible. I was always sorry right away. But I remember I’d rather die than apologize. Not any more, though. Now if I feel I’ve been wrong it’s nothing at all for me to apologize.

I wish it were that easy to, you know, analyze yourself on everything. And I was always sort of curious about what it would be like to be analyzed, because I’d seen it in the movies and I’d often wondered what would happen. Well, last January this reporter took me to a psychologist to try to find out—I don’t know—what makes me tick, I guess, and I enjoyed it! I lay down on the couch and he talked. I mean, we carried on a conversation, about the Paar show mostly. And I took the word test and, uh, the ink-blot test and I drew pictures looking in the mirror. So the very last thing he said was he would never advise psychoanalysis for me, that it would probably ruin my earning power. Because, he said, one of the things that made me interesting was that I was different and he said, once I learned what made me act differently from other people I might conform and not be as interesting any more.

To me, my worst fault is disorganization. Like, well, I keep everything and it’s usually in a pile and it takes me a while to dig it out. I don’t always find what I’m after, either. Like the time I flew to Miami with the Paar show. When I got to the airport I went all through my things and I didn’t have my ticket. Jack just looked at me and said, “How you ever gonna get to the moon?” When we got home I discovered the doggone ticket had flown all the way to Miami and back mixed up with my music.

I also admit I have a temper—at times. I, I think it’s a luxury that you can’t afford too much, because other people won’t put up with it. If I have a tendency to lose it I just sort of, well, count to ten. Like when they start asking you how old you are. I think a performer has a perfect right to conceal his true age. Now for me, I don’t conceal mine. I say I’m twenty-nine because I don’t want to be thirty.

Things I do like—music, reading. With music, well, I love all kinds, really, but I lean toward classical, and I like ballet music, naturally. As for reading, I just read everything, from movie magazines to scientific magazines. And books,—of course, especially biographies of show people. And I have a lot of Thurber and Benchley.

I don’t retain everything I read exactly as it is. But sometimes something somebody says will remind me of something I’ve read and I’ll be able to recall it. That’s the way it is with everything. If somebody asks me on the spur of the moment I can’t remember, but if I’m just sort of casually reminded of it, or it’s apropos, then I do.

Like at first, Jack Paar used to always ask me on the air, “What did you do today, Dody?” And maybe I’d been rushing around since nine in the morning but I’d just go blank. People are always asking me—you know—what do I do all day. Well—I’ve either been rushing to a rehearsal or from a rehearsal, or to a ballet class, or washing my hair, or taking a bath, or learning material, or washing my stockings, or answering phone calls, or answering mail, or taking a nap, or reading.

Since I’ve been on television, well, naturally, life is even more hectic. So many people see you and—you know—they recognize you on the street and stop to talk. And I love to talk to people. Then there are interviews and pictures. Seems like I’ve posed for enough pictures to, I don’t know, set up my own rogues gallery. And some of the photographers make you do the craziest things. Like one had me drag out all the hats I had in the closet. I mean—for heaven’s sakes, I’m no Lily Daché. I had hats, hats, hats all over the place for days because I had to fly to Hollywood for the Gobel-Fisher show the next morning.

That was last March and it was lots of fun. It was really my, well, my first big guest shot is what it was. And George and Eddie were so kind. Ethel Merman, too. It was my first trip to Hollywood and I guess that’s always a thrill. Of course, I was only there for a week and I spent six days of it working but I did get to eat at the Brown Derby and the Beachcomber and La Rue’s, where I saw my favorite—Dinah Shore. On my last day some friends drove me out around Laurel Canyon and the San Fernando Valley and Malibu Beach. The scenery is so beautiful, and the air! It’s just marvelous! They had a party for us at the Beverly Hills Hotel after the Gobel-Fisher show. Eddie had to go home early because Debbie had just had a baby.

That show meant a lot to me, because you reach a whole new audience in the early evening hours. George and Eddie have 60,000,000 viewers! You reach new people in the early morning hours, too, like on “Today.”

When my appearances on the Paar show were first cut down, everybody rushed to ask me how I felt. And it was so sudden that—well, I—I probably said all the wrong things. At first I was sort of unhappy about it, naturally. I didn’t realize then that it was really a step forward—more money and the opportunity to do guest shots on other shows. I get so many offers now it’s just wonderful. Even the Theatre Guild wants me for a play—“Dulcy.” I’m going to do it this summer for six weeks. We open in Chicago in July for two weeks and close in Westport in August. I forget where we go in between—I think Falmouth, for one, and Ogunquit. Anyway, I’m really thrilled because I’d like to establish myself as an actress. So things really do happen for the best. But one thing I’d like to make clear is that I always have been and always will be grateful to Jack Paar for the opportunity he gave me on his show.

Some people think I used a teleprompter on the Paar show but I didn’t. I just talked off the top of my head. And sometimes a perfectly innocent remark would get a huge laugh. Like—well one night on the show, Mary Margaret McBride was trying to make Jack cry with a sad story about how she had never had a Christmas tree. But she didn’t get one tear. So she turned to me and she said, “What’s the matter? Doesn’t anybody care that I never had a tree when I was little? What did I do wrong?”

And I said, “I think it’s because you tell it in a mink stole.” And everybody screamed. But I wasn’t trying to be funny. I was just sort of trying to analyze it.

Sometimes we’d have unusual things to show—new articles just on the market. And one night, after Jack had shown this address book with a mink cover, he gave it to me. But the next day the office called frantically and said I’d have to give it back, that it cost sixty-nine dollars and nobody on the show was going to pay for it. So that night I gave it back to Jack on the air and he was sort of apologizing, and I said, “Oh, that’s all right. I didn’t want it anyway.” And I kind of stroked the mink and I said, “I’d just have to put it in storage for the summer.” And everybody screamed but to me that made sense.

I don’t understand it, but people say it’s my delivery. I can’t stand my own voice. And when I saw myself in a kinescope for the first time, last March, I thought I’d faint! Afterwards I was talking to my mother and I said, “My mouth—I’ve never seen such a big mouth. I do so many peculiar things with it.”

And she said, “Well, that’s what I told you. You screw your mouth up when you talk.”

It’s funny when I think how I ended up with people laughing at me, after I’d started out to be a ballerina. During summer vacations I would come to New York and make the rounds of the big ballet schools.

It was all very exciting to me and I think, well, you know, it can’t help but make you kind of different from other kids. I know in high school I kept pretty much to myself. Just sort of settled for one or two close friends. Oh, I went out on dates and things like that. But, well—I can’t say they were the most important things in my life.

I’ll never forget my first date, though. We went to this dance and on the way home—I guess I was about sixteen and at that age—well, we got to bickering and I had always thought it was so glamorous to walk home. I’d heard about girls walking home, so when he stopped the car for a red light I got out and ran. I had to walk at least three miles and he hadn’t made one pass at me! Well, I never did that again. When I got home he was parked out front and the poor thing was so scared. And everybody was up and I was tired and bedraggled.

Now that I think about it, I guess maybe I’ve been running all my life. Like I almost got married twice. Both times I was in Broadway shows and I’d get this crush and on the spur of the moment we’d dash down to City Hall for a license. The first time we didn’t even know you had to have a blood test first! So we’d get the license and both times I just let it expire. I just didn’t get married fast enough, I guess.

The thing is—well, men want to change me. And I don’t like it. Or they’re jealous, or they don’t think I love them enough, or I’m too independent and—oh, I don’t know. One thing I know about myself, I’m not aggressive and so I’m the one who has to be pursued. And yet I don’t like an aggressive man, so I’m in a terrible state. Like at parties, I’ll never seek out the handsome men. I’ll go join someone who’s sitting quietly in a corner or something like that and I’ll go over and, you know, so they won’t feel so lonely. Usually it turns out it’s someone who’s all mixed up and then they get terribly attached to me and that’s not the kind of guy I want, either.

Right now I’m too busy to worry about marriage. When I was on the Paar show I’d have to be at the theater by 9:00 p.m., even though the show doesn’t go on the air until 11:15, and then I wasn’t through until 1:00. Most of the guys I know have to get up in the morning. So when I didn’t have a date after the show I’d usually hop into a cab and head for the Stage Delicatessen or maybe the Carnegie Delicatessen, where I’d have a sandwich or a bowl of soup. After I ordered, I’d usually head for the phone. I have this friend who liked me to call after the show and we’d usually discuss it. If I’m depressed about anything it sort of helps me to talk it out.

I guess show business has been my whole life ever since I got out of school. I wasn’t a bit scared about leaving Columbus to come to New York, but Mama was sort of apprehensive. Just before I left she got out some corny old book called “What Every Girl Should Know” or something and had me read it, and of course I’d known all that stuff for about—well, as long as I could remember!

And my poor father, who didn’t want me to go on the stage anyway—he thought I should be something practical like a stenographer or a nurse—his famous last words were, “Watch your slip that it doesn’t hang, because that looks awful.”

Anyhow, in New York I lived at the Rehearsal Club and I danced in the ballet at Radio City Music Hall once in a while. Then I did a lot of Broadway shows like—well, the first was the road company of “High Button Shoes.” I used to sort of clown around backstage and recite these corny old poems like “Yukon Jake.” When we did “Wonderful Town” in Dallas, after the New York run, Imogene Coca—she replaced Roz Russell—loved the way I did these old poems so she—well, when we got back to New York she gave a party and had me perform for Julius Monk, who booked Le Ruban Bleu. I guess he thought I had something because he advised me to, well, work hard and get some new material and audition for him again.

So I gave up everything—I’d been doing small parts on TV shows—and went to work on a comedy act of my own. Then I did some night-club shows and a stage revue. Then in July I was interviewed by Jack Paar for “Tonight,” which is what it was called then.

Meanwhile, I had gotten this apartment in the West Fifties so I guess I was sort of ready to settle down to a more or less steady job. It’s a nice sunny apartment, with lowered windows and Victorian furnishings, but it just isn’t big enough any more. I have a room-and-a-half with a hide-a-bed. The living room is quite large but there’s no place to put the fan mail and all the nice presents people send me. They’re sort of piled all over. And I have bookcases filled with my various and sundry books and material and records and anything else I can stick in them. As for my one closet—one of these days all that stuff is just going to rise right up, form a posse, and lynch me!

But I don’t really need a whole lot of closets, because I never did fuss much about clothes. I like to dress casually. Low-heeled shoes. I think women look better in high heels, but there’s something about comfortable clothes that I love. Besides, I don’t need heels for height. I’m five feet six and I never weigh over 118 pounds. As for makeup, all I ever wear is mascara and lipstick. Sometimes some eyebrows. But I’m not the type to constantly fuss with a mirror. When my lipstick comes off, half the time I forget to put it back on.

One thing I never can understand is why people seem to think that comedians are really sad at heart. I guess that’s always been so—you know, the laugh, clown, laugh business. As far as I’m concerned, well, I may have moments of sadness, but I’m not too sad. I cry very easily, especially at sad movies, and I know sometimes people say that I look sad, when I’m just sitting quietly, but I’ve always looked that way. Even my baby pictures. My mother used to say to me, “You have such a sad little face.” Comedy may be motivated from that. From your own personal sadness, I don’t know. Or some incompleteness about yourself that makes you want to exhibit yourself and make people laugh at you, make a clown of yourself—because that’s what comedy is.

You know, it’s strange. I think people, well, I really think they like to think of you as sad. They’re always asking me, “Are you lonely? Do you think of yourself as lonely?” Well—I don’t think I am. I think everybody needs companionship, but I require a certain amount of privacy, too. Of course, you can, you know, stand to be alone just so much and then suddenly you look up and say, “Where’s everybody gone!”

THE END

—BY DODY GOODMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1958