Brotherhood Is A Four Letter Word

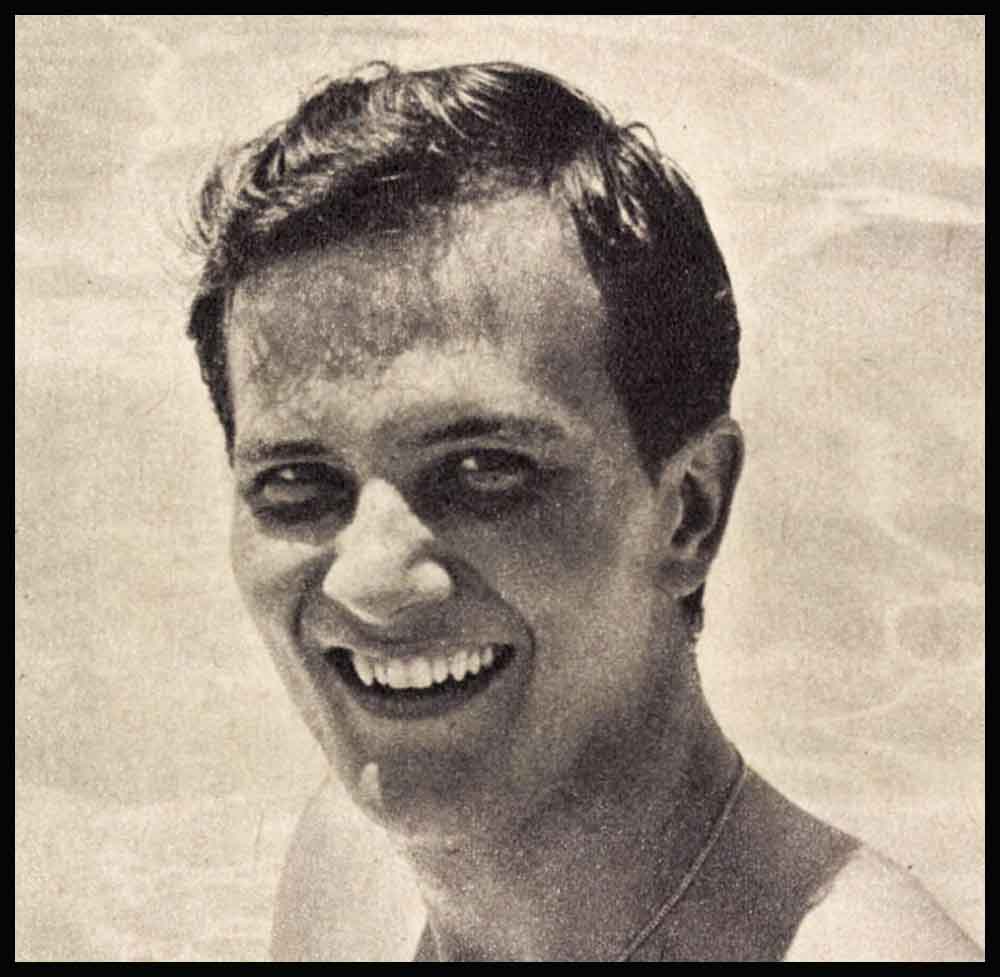

An expectant hush settled over the crowded banquet hail in the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Pat Boone stood in the center of the dais ready to acknowledge the honor just paid him. In his arm he cradled a plaque—the Brotherhood Award presented annually by the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

Pat cleared his throat and said, “First of all, I think you’ve made a mistake here!”

There was a gasp from the crowd.

“You’ve given me this award for promoting brotherhood,” Pat went on. “Yet you know I have four daughters. I’ve helped the cause of sisterhood, but brotherhood—I don’t know. . .”

Pat Boone’s disarming quip amused everyone— but fooled no one. Everyone in the room knew that there had been no mistake. Pat deserved the award.

It is unlikely that the honor has ever gone to a person whose credentials are more unusual than Boone’s. Pat is an Evangelical Christian, a dedicated member of the Church of Christ who frankly believes in converting others. He will not appear at benefits to raise funds for the teaching of any religious doctrine other than what he believes is scriptural. On screen, he has refused to portray clergymen or lay advocates of any faith other than the Church of Christ for fear such roles might be mistaken as endorsement of a religious belief different from his.

“I do have certain problems,” Pat reveals, “because while I love everybody and I have great respect for people of other faiths, I still feel my own faith and my membership in the Church of Christ is very vital to me. I’m not so liberal that I believe no matter how you worship God it’s all right as long as you feel in your heart that you’re right. I’m more fundamental than that.”

Yet despite such a commitment to his own church, Pat possesses a shining warmth and engulfing love for his fellow man. Where Pat Boone walks, religious and racial prejudice never cast their grotesque shadow. He lives brotherhood and fights bigotry not only on public platforms, where his hearers are sympathetic, but in places where bigotry is subtly concealed and deeply rooted.

Pat Boone dares brotherhood in his own family circles, where ancient biases against the Negro have not fully disappeared. He fights for brotherhood in a restricted golf club, where membership is denied a Jewish friend. In his Office or his living room, wherever a chance conversational remark may betray a blind spot of prejudice, he challenges bigots in frank encounter. But he chooses to challenge them with a four-letter word spelled L-O-V-E.

His plaque from the National Conference of Christians and Jews is not an entirely new experience. Pat has received many other brotherhood awards on a more intimate level. He has mezuzahs, a Lion of Judah, St. Christopher and St. Genesius medals. Sometimes he wears them around his neck, sometimes he puts them on his key ring—but the friendship these tokens symbolize he wears always in his heart.

“The other morning,” Pat explained as we sat in his dressing room at 20th, “Rafer Johnson and I were playing on 20th’s basketball team in a game against Warners. The other team wore shirts, but we didn’t. Rafer had a mezuzah on a chain, and a guy asked me if Rafer was Jewish. I said I didn’t think so, that I suspected it was a gift from a friend, and that Rafer wears the mezuzah the same way I wear it—as a token of friendship. It doesn’t mean anything to me religiously, but as a token of friendship it does.

“If a friend gave me a bracelet or a ring, or even cufflinks, I’d certainly wear them,” Pat ventures. “But what makes religious tokens different is that while they don’t represent my religious beliefs they do mean something religiously to those who give it to me. It’s almost as if they’ve given me a small part of themselves rather than just something they’ve bought. It’s a sharing of spirit as well as a gift.

“One day,” Pat smiles, “I was on the beach when a Jewish lady noticed that I was wearing a mezuzah. She came up to me and asked if I were Jewish.”

Sometimes Pat doesn’t even have to wear a religious item to be welcomed into a certain religious group.

“Just because we have four children—ages three, four, five and six—a lot of people assume I’m Catholic. And the fact that I’m descended from Daniel Boone seems to draw me to a lot of people, too.”

Not too long ago when Pat was in Miami Beach a woman came up to him and said, quite seriously, “Did you know we were cousins?”

Pat had to confess this knowledge had escaped him.

“Well, we are,” the woman assured him. “I’m descended from Daniel Blum, and so are you.”

“It seems I’m just kin to everybody,” Pat concludes with a warm smile.

Pat, for example, is kin by friendship to a Hungarian Jew named George Unger. Unger, an ex-fighter turned jeweler, lives in New York. Pat describes him as a hulking man whose heart is as big as his physique, a man who quietly donates hundreds of braille watches to the blind every year. Pat is always touched but never surprised by Unger’s generosity.

One day Unger pressed a present into Pat’s hand and growled, “Here, Merry Christmas!”

Pat opened the package and found a heautiful silver Lion of Judah—the lion’s foot on a diamond and a ruby in his eye.

“You’re not Jewish,” Unger said, “hut I want you to have it.”

Pat has a gift for awakening similar warmth and affection in friends of every color or creed.

“My manager, Jack Spina, being Catholic, has given me a St. Christopher medal,” he acknowledges. “I’ve also been given a number of St. Genesius medals—St. Genesius being the Catholic patron saint of dramatic arts. If a Catholic actor gives a St. Genesius medal to a non-Catholic actor, it’s as much as saying, ‘Look, we’re in the same fraternity and I give this to you.’ You know, it’s a bit more than something else you might wear.”

Pat’s rapport with his fellow man springs from unusual familiarity with religious traditions other than his own, and from a background of tolerance in his immediate family.

“I think I was raised in an unusual family,” Pat says. “I grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, in the heart of the south. In Nashville, I don’t know of any real prejudice against Jews, but of course there’s a great deal of prejudice normally and generally toward the Negro. Yet in my immediate family there was no prejudice whatsoever toward Negroes.

“My mother and father, being genuinely religious people, saw no reason to look down on somebody or think less of him just because his skin happened to be a different color, or his religion or race was different. My parents both have open, generous hearts. I was blessed to grow up in a terrifically open-minded, deeply religious family—genuinely religious, not a fanatic or really narrow thing.”

This tolerance, Pat concedes frankly, does not extend to all members of his family.

“Others of my relations,” he points out, “have always considered Negroes still kind of slaves . . . ignorant and no account, you know. Even now some of my relatives still feel the Negro always will be inferior to the white man—in mental capacity, in social habits, in ability to cope with life in general. They just feel the Negro is inferior. I regret this, and I’ve talked to them about it.

“These relatives expressed disgust at the fact that I had a Negro performer, Johnny Mathis, on my Thanksgiving show. They wanted to know why I couldn’t just as easily have had a good white performer. What could this fellow possibly contribute that a white singer couldn’t? They had discussed the matter while eating their Thanksgiving meal. When I heard about it. I had to write to them.

“The letter wasn’t belligerent,” he nods. “These happen to be people I love, and I can understand that this has been part of their heritage. They’ve been raised this way. All their lives they have been taught that the Negro is inferior.”

So he wrote to them not with anger—but with love.

“I understand,” he said in his letter, “that all of you were eating Thanksgiving dinner and commemorating the freedoms of this country and celebrating the atmosphere that has made this country great. Yet at the same time you couldn’t understand why I would have a very good singer on my show, a popular and talented young singer, just because he was a Negro. There seems to be a real incongruity there, you know.”

However eager he is to overcome bigotry, Pat is not naive enough to expect every barrier to fail in his friendly path. He took on an ancient bastion of snobbery—one form of prejudice—when he tried to get his Jewish pal, Buddy Hackett, accepted for membership in a country club to which he belongs.

He talked to the club pro, other members and even went to work on the membership chairman. But it was all to no avail. Defeated and dejected, he phoned Buddy.

“They told you they just didn’t have any openings, right?” Buddy anticipated.

“No,” Pat said forthrightly. “It wasn’t that. Each of the fellows I talked to said there’s nobody they’d rather have in the club than you, but there were rules and there was nothing they could do.”

Buddy was taken aback by Pat’s candor.

“You mean they actually told you why they won’t let me join, Because I’m Jewish, and you don’t mind telling me?”

“Why should I he to you, Buddy?” Pat said. “I want you to be in the club. and I’d gladly sponsor you. All I know is that you’re my friend.”

There was a long silence. Then Buddy said, “I want to thank you for your courage. Pat.”

“What do you mean, courage?” Pal protested. “There was no courage.”

“Oh yes there was,” Buddy insisted. “It took a lot of guts for you to stick your neck out the way you did—knowing the restrictions and still going around saying you had a Jewish friend you wanted in the club. That took a lot of guts, Pat.”

Pat’s heart went out to Buddy, and he was anxious to soften the hurt.

“Anyhow,” he told Buddy, trying to con- sole him, “I want you to come as my guest.”

“I can’t,” Buddy declined. “I hope you understand why.”

Pat instinctively understood.

Pat’s devotion to brotherhood is not all instinctual. He is an avid student both of the old and new testaments. He knows Jewish history, and has undisguised admiration for the aspirations of Jews in the stout new State of Israel—aspirations which Pat likens to the American struggle for independence. In fact, out of the deep well of sympathy for the struggle to create a Jewish homeland came the inspiration that impelled Pat to write the lyrics to The Exodus Song.

Pat had bought the recording, and was so enchanted with it he played it again and again. It was Christmas Eve, and he was sitting in his living room.

“I got chillbumps listening to that music,” Pat says. “In addition to being familiar with the history of the Jews, I’d read Leon Uris’ book. Knowing the backgrond of the story and listening to the song, an idea came to me.”

The idea was translated into words, and the words rushed to impatient fingertips. Pat reached for the first piece of blank paper he could find and wrote the lyrics that the music demanded—wrote words that caught his answering excitement to the drama of an enslaved people’s liberation.

“This land is mine!

God gave this land to me,

This brave and golden land t o me. . .”

He finished the lyric that same evening. As if moved by the hand of God, he urgently scrawled the lyrics with a ballpoint pen, and used two Blue Chip stamps pasted on the white surface to indicate an instrumental bridge.

When he had finished, Pat picked up the paper to re-read the song of Jewish liberation he had created that Christmas Eve. It was then he discovered he had written the lyrics on the back of a Christmas card!

Pat Boone is not a professional lyricist. Dozens of pros had submitted lyrics for The Exodus Song. The picture’s producer, Otto Preminger, had turned them all down. Randy Wood, the astounded head of Dot Records in Hollywood, got on the transcontinental phone and read Pat’s lyrics to music publisher Stan Stanley in New York.

“Wonderful!” Stanley exclaimed. “Who wrote it?”

“Pat Boone,” Randy Wood said.

An amazed Stanley presented the lyrics to Preminger. One earful was enough. Thus The Exodus Song came to life with Pat Boone’s lyrics.

When Buddy Hackett heard the story of how Pat had come to write the song, he was overcome with emotion.

“Pat,” Buddy said, “I have to make you an honorary Jew immediately.”

Whereupon Buddy took out a gold religious medal on a chain and offered it to Pat.

“It’s a mezuzah, Pat,” Buddy said. “I want you to have it. Will you wear it?”

For an answer, Pat put it around his neck then and there.

“Sholom,” he smiled at Buddy.

“Sholom,” Buddy said.

Sholom is a Hebrew greeting. Like the Hawaiian aloha, it is a substitute for hello and good-by. Corning or going, it means peace be with you. And it means something else, too. It means love—Pat’s own special four-letter word for brotherhood.

—BY WILLIAM TUSHER

Pat Boone stars in 20th’s All Hands On Deck.

It is a quote. MOTION PICTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 1961