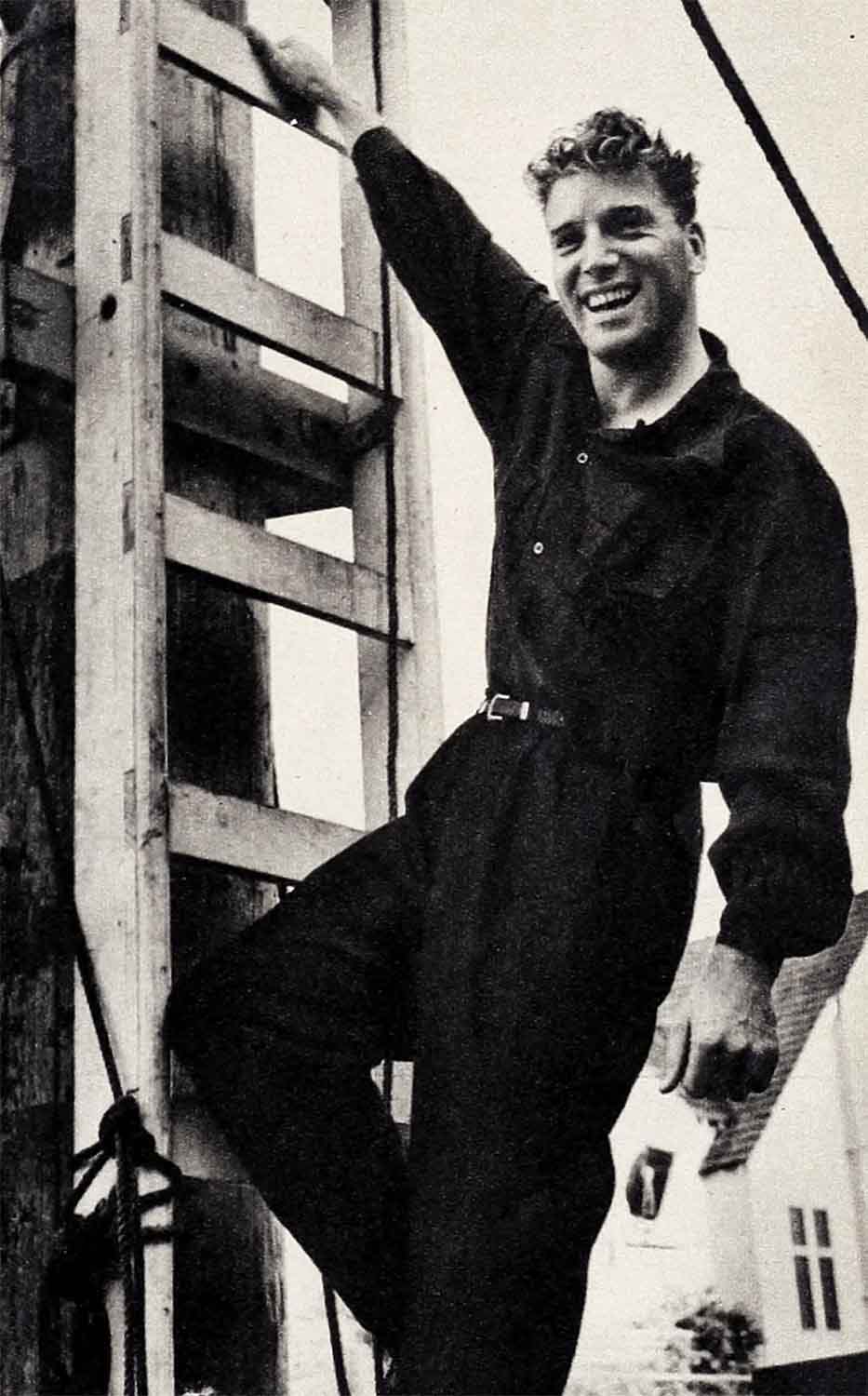

Big Guy Burt Lancaster

A frame like a stevedore’s, blond hair with a butch haircut, an impolite insistence in his voice and a jaw line you feel you have met before—add them up and they total “Burt Lancaster.”

As “Swede” in “The Killers,” his first picture, Burt hit the screen with instant impact. “Swede” Lancaster really killed ’em—including the producers. Contracts and assignments fluttered down on his head like snow. “Brute Force,” “Desert Fury,” “I Walk Alone”—he walked right through them.

But Burt is “tired of walking through walls”—tired of prison escapes, gun battles and the brutality attendant on the top roles he has played in less than two years. His present portrayal in “All My Sons,” at Universal-International, finds him very, very happy.

AUDIO BOOK

“I play an average guy—a solid character with high standards. A fellow whose flyer brother is killed because of faulty equipment, and after the war finds out his father did the profiteering. Edward G. Robinson is my father.”

Burt feels it’s “a major step forward” in the direction he wants. On the other hand, there is always the danger he may go too far from the Lancaster already tried and tested. In his case, however, the results could never be too formidable. Perhaps, because the most useful bit of equipment ever brought by any actor to Hollywood is Burt’s ability to “break a fail.” He learned it the hard way, working in a circus for $5 a week and board as a “stick actor”—a fellow who performs on the horizontal bars.

When Burt quit college and started rehearsing in a New York gym with a pal, he’d had something more elegant in mind as a salary. And, after thirty-four weeks of rehearsing, thought it would be a cinch to collect it from, say, Kay Brothers, then breaking in a Big-Top troupe in St. Petersburg, Florida. That’s a long way from New York City on a map—in a recalcitrant jalopy it is even longer. The car gave up, but the boys didn’t, making the last ninety miles on foot. After listening to their demand for a three-figure starter, the gentleman in charge replied, “Give you $5 a week and keep.” They decided he was making a fair compromise.

“He was a real old-timer,” Burt tells, “and I’ll never forget the first time I climbed to the bar to show him what I could do. I was so excited, I fell right off. I got up from the ground, surprised and woozy, and tried it again. It was a trick I knew I could do, but after the sixth plunge of eight feet, as I lay on my back, my tights ripped and each vertebra separated from its brothers . . . I knew it was no use. If I could have accomplished the darn thing, the old-timers were too weak from laughing to appreciate it.”

Then, there was the neat trick known as the “swing around.” Conscientiously performed by Burt each day, it never failed to remove several strips of skin from the back of the knee to the ankle.

“By the end of the week I could hardly stand. A mule-trainer gave me some salve they use on mule-hocks, but it didn’t help. One day, the owner asked me what was wrong. I told him I couldn’t seem to get my legs to heal. ‘That’s simple—’ he said. ‘Lay off that trick for awhile and fill in with somebody else—’

“I stood there, sort of paralyzed. It just hadn’t occurred to me that although ‘the show must go on,’ there might be a less harrowing way of continuing it. I was the most relieved kid you ever saw—”

“Kid” is right, for the Lancaster was then a brave nineteen.

After his skin-the-calf debut, Burt and his partner advanced through various sawdust stages to a feature spot with Ringling Brothers, and from there to vaudeville, to balancing atop a long pole held by his partner.

The WPA Theater Project allowed him to exercise his voice. After WPA, he worked. a succession of small-time fairs, carnivals and hotels. The pay was even sketchier than his skits, so he went to selling at Marshall Field’s in Chicago. He also went to working for a refrigerating plant, the fire department, a meat-packing plant, and eventually, back to his home town of New York where he landed a good job with Columbia Broadcasting. Before he could get used to the feeling of collecting a weekly pay-check, he found himself in the Army. He trouped soldier shows through North Africa, Austria, Italy and other European stands.

September, 1945, found Burt back in New York for demobilization. Fate was about ready to give in. It happened in the elevator of the Hotel Royalton to be exact.

Entering with him on the ground floor was a Broadway producer looking for a fellow—a Lancaster—to play the lead in “A Sound of Hunting.” The CBS talent-selling job with its steady pay was awaiting the soldier’s return, but Burt never gave it a second thought. Within a few days after the opening of “Sound of Hunting,” he had bids from seven of Hollywood’s major movie-mills. It was Hal Wallis who got him on a contract. But it was Mark Hellinger who first got him on celluloid.

“The amazing thing about those first reviews—” Burt says, speaking of the critics’ raves about “The Killers,” “is that most every one of them spoke of the ‘ease’ of my first performance. Looking back, I can’t remember doing a scene in which I wasn’t shivering so badly I was afraid there’d be three or four of me on the screen where only one was needed.”

It is not the money involved, but a determination not to let anything best him, which is the greatest reason for his satisfaction in achieving screen success.

“I’ve never had too much feeling for material holdings,” he says. “When I was an out-of-work acrobat, I often stood around the corner of 42nd Street wearing a $100 suit—not to put on a front, but because I usually bought according to the amount I had in my pocket. I bought a $5 tie if I had $5, or if I had a dollar I bought a dollar one. I remember buying a $14 pair of shoes, because that was what I had with me, and then having to walk home some sixty blocks.”

He admits, however, that his view of things nowadays is not quite so nonchalant. His feet, his heart and his tomorrows have been secured by the blonde Norma Lancaster. Norma is “pretty wonderful,” as he discovered to his surprise, after knowing her just a few weeks in Italy, where they met when she went overseas with USO.

“I didn’t go for Norma at first, but as the days went on and I saw her remaining as sweet and unaffected as when she first arrived, I knew she was lovely inside as well as out.”

Norma, being “too good a housewife” to do much rushing around, they’re taking it easy, living in a surf-side house at Malibu Beach. Except when they have a few close friends in for dinner—that’s the kind of rushing ’round she prefers.

For the baby they’re expecting, Burt has no specified ambitions. He hopes he’ll be a “good kid, who grows up into a worthwhile adult. I hope he’ll be smart enough when he has to face life on his own, to face it without sham—to look at it clearly, and put nothing but honesty into it.” Like all parents, he’d give his heart to save the next generation “some of the confusion of this one.”

This last, he thinks he might help along better as a producer instead of an actor. His producing urge is so strong and so continuously expressed, that when calling on his close friend Mark Hellinger, he must needs send in word whether it is “Lancaster, the actor,” or “Lancaster, the producer” who wishes a talk.

His yearning, as a producer, would be to put his “own concept of good and evil, but mostly of beauty, on the screen. I believe that if I tell you I’m a bad fellow—and glory in that fact—I am a bad fellow. But maybe, I’m a fellow who does something you consider ‘bad,’ but do it only with good in my heart. Then the deed is not evil. I’d like to prove that the popularly-drawn lines of good and evil are not ones which necessarily will stand up—” He hopes to prove this with “Kiss the Blood off My Hands,” his first producing-starring film.

This ambition proves Lancaster’s fairly recent acquaintance with the screen. Sooner or later he will find himself up against the barbed-wire defense of the censor’s office, which says good must be “good” in black and white, and “evil” not only likewise, but necessarily so.

Equally exciting is Burt’s ambition to write, produce or just act in a real circus story, a subject on which he will talk for unlimited paragraphs, and keep you completely enthralled:

“Few people realize what an integral piece of Americana the circus really is. The first public sports events were the leaping contests, usually presided over by the mayor of the small towns, with circus leapers encouraging and challenging local talent.

“The circus stars were as important as the movie stars of today—more so. They brought the world to the crossroads, because in those early days circus people were the only ones who had travelled everywhere and had seen everything.

“Routing the circus so that it reached each town just as the tobacco crop or lumber mills paid off was a matter of much battling between outfits and some colorful fights really ensued. Most of all, the moving of those huge troupes of people and animals was a Science. When Barnum & Bailey toured Europe, Kaiser Wilhelm sent a detachment of officers to observe how this troupe movement was done. Many of their devices play an important part in war-time troop movement today.”

The Lancaster circus classic is still something to look forward to—and according to the number of picture assignments lined up for him—you’ll have to look pretty far forward.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948

AUDIO BOOK