In All The Excitement Kim Novak Found Someone New

It was a lovely day in Los Angeles. A soft breeze was blowing, and there wasn’t a trace of smog. Kim Novak came out of the restaurant, having just concluded a luncheon interview, and walked down to the corner of Gower and Sunset Boulevard. She stood waiting for the light to change.

“Kim. Hello.”

Kim turned to face a tall and slender girl with long dark hair. She looked very familiar.

“Hi,” Kim said, flashing her familiar friendly smile.

“Do you remember me?” the girl asked. “I used to live at the Studio Club.”

“Oh, sure. Of course. How are you?”

“Look, Kim,” the girl said. “I have a friend who’s a producer on radio. He has this show that goes on the air three times a week. . .

Kim listened intently. The story was a little involved. What it boiled down to was that the girl wanted Kim to make a guest appearance on her friend’s radio show.

“Gee, I wish I could,” Kim said, and smiled. “But it’s impossible. All these things have to be cleared through my studio.”

“Oh?” The girl’s eyebrows registered disappointment and a trace of disbelief.

“I’m sorry, I really am,” Kim said. “But that’s the way it is. Now that I have a contract, the studio makes all those decisions for me. And besides—” she smiled, somewhat wistfully, “I just don’t have the time. You see, they keep me pretty busy.”

As she walked back to the studio, Kim wondered if her friend believed her. She sincerely hoped so. She didn’t want to appear stuck-up or too busy for old friends. But what else could she do? She had told the simple truth, even if it did sound a little thin.

Kim reached into her pocket and pulled out a dog-eared piece of yellow paper. On it was her day’s schedule, jotted down in her personal scrawl:

9:00 a.m. Studio—hair appointment. (Don’t let them trim it in back)

10:30 a.m. Studio—wardrobe fitting. (Would that lavender gown do for television?)

Noon. Naples Cafe—publicity interview and lunch. (Keep calories down! Watch it, girl!)

2:00 p.m. Beverly Hills—photo sitting; sweaters and skirts. (Better take shorts, too)

3:15 p.m. Dentist appointment. (Ouch!)

4:00 p.m. French lesson. (Allons-y! Les femmes et les enfants d’abord!)

5:00 p.m. Driving lesson. (Beep! Beep!)

8:00 p.m. Studio — Batomi’s drama class.

“Golly!” Kim said to herself. ‘Tm booked up every hour on the hour!” When Kim arrived at the studio, the girl at the reception desk said, “Kim! Mr. Horwits has been looking everywhere for you! It’s about your boat reservations for the Cannes Film Festival.”

“Okay,” Kim said without breaking her stride. “Be there in a second. Right after I powder my nose.”

She disappeared through an inner door. Then she opened it again and stuck her head out. “Marje, honey, will you call a cab for me? Tell them I’ll be ready in ten minutes.”

Later, in the cab headed for Beverly Hills, Kim leaned her head back and closed her eyes. A few years ago she had been plain, gawky Marilyn Novak. Now she was Kim Novak, and of course she wasn’t plain any more.

A few years ago she had reveled in extravagant dreams of someday becoming a glamorous movie star in Hollywood. And now here she was, with stardom right at her fingertips. And all the rest of it, too—the lights and glamour, the beautiful gowns, wonderful people. Everything was just perfect. Or was it?

There was one thing that hadn’t worked out according to her original cloud-nine plan. In her dreams, Kim had envisioned everything being conducted with an easygoing, even-paced calm, with everyone speaking in carefully modulated and extremely pear-shaped tones. Thus, she had not been entirely prepared for the tugging and shouting that sometimes serves as a background during the making of a movie. And all the confusion! It was bewildering, to say the very least.

The hard work was fine. Kim understood that, and she was prepared for it. When a new girl goes up against such veterans as Bill Holden, Frank Sinatra, Rosalind Russell and Tyrone Power in her first movies, some extra-curricular effort is to be expected of her. This Kim gave, and gladly. Of course, there were a few times when shedding some tears helped ease the pressure of high tension and fraying nerve ends. But when the tumult was all over, and the picture was “in the can,” she had envisioned long recuperative weeks in the mountains or at Palm Springs. But this definitely was not what happened.

“Between pictures we get ready for the next one,” she was told at the front Office. “Or we hit the road and help to sell the one that’s already out.”

Hitting the road, it developed, meant personal appearances in the theatres of a dozen or more cities. It meant a barrage of popping flash bulbs amid autograph parties and television appearances. And a seemingly endless round of publicity interviews with members of the press.

Well, okay. If she had to do it, she would.

“Fine, darling,” they told her. “That’s our girl. We’ll order the plane tickets right away.”

“No!” she said, putting her lovely foot down for the first time in quite a while.

“No planes. They make my ears hurt. And besides, I don’t like flying. Get the tickets for the train.”

Traveling East on the train, Kim caught up on her sleep. She got ten hours a night and sometimes twelve, which was heavenly. She read Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again. She indulged in a favorite pastime—philosophizing about life. And she wondered about the people she could see from the windows of her train. “What do you suppose they do for a living?” she said to her companion, Muriel Roberts. “Do they have children? Do they like dogs? Do they go to the movies? Are they happy?”

In Chicago, Cleveland, Toronto, Montreal and Philadelphia, Kim met the people, talked to them, and signed autographs by the hour. Was it fun? “It was exciting!” Kim said later. “And wonderful! It was a big thrill to be received with such warmth and friendliness. Everywhere I stopped they seemed to know all about me. And the nice part was that they were rooting for me and seemed to believe in me. That made me feel good. It was really something.”

But that night, when she crawled into her hotel bed, Kim was so tired her bones ached.

In New York, she lived in a luxurious studio-owned suite on the 19th floor of the Sherry-Netherlands Hotel. “Well, get me!” she said, as she floated in comic grandeur through its nine rooms and three baths.

Almost every night she went to the theatre. “I guess the studio felt that seeing the Broadway plays would be good training for me,” Kim explained. “That was just great with me. I saw practically every show in town. I loved ‘Janus’ and ‘The Lark’ and ‘No Time for Sergeants.’ But I most enjoyed ‘The Great Sebastians,’ with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. Their timing was simply marvelous. It was like a liberal education in acting to watch their performance.”

Meanwhile, Kim’s days were crammed full of appointments that soon began to fit a definite pattern. The telephone rang with the morning call at 8 a.m. “Okay, okay,” Kim said, prying her eyes open. She stretched and wriggled her toes. “Well, here we go again!”

A quick shower, then breakfast, which is always the same for Kim: large orange juice, half a grapefruit, and coffee. And, soon after that, the first interviewer of the day arrived.

“Are you on a diet?” asked the newsman, noting the low-calorie content of her morning repast.

“Well, of course,” Kim said. “I keep my sweets and starches down to a minimum. Doesn’t everyone these days?”

The second interview was scheduled for noon, usually over lunch at Armando’s or Sardi’s. These celebrity spots could have been fun for Kim, except that she always had to concentrate on the questions and answers.

“Is it true, Miss Novak,” asked the inquiring reporter, “that you always sleep with your head pointed north and your toes pointed south?”

“Well, no,” Kim answered. “I don’t think I point in any direction. You see, I usually scrouge up into a soft of lump or ball. And I wear pajama tops, in case you plan to ask.”

The afternoons were devoted to posing for pictures. Kim lugged her model-type “swag bag” to one of the big commercial studios and sat for color shots or cover portraits. Or she journeyed around town while a magazine photographer snapped candids of her. Then she rushed back to the hotel for a quick shower and a change of clothes to be ready for a 5 p.m. meeting with a columnist or a radio reporter.

Inevitably, the interviews fell into a pattern, too. Most of Kim’s questioners wanted to know how she got her start in the movies. So she told them the story of the days preceding her studio contract when she opened and closed refrigerator doors in a touring appliance show, and bore the unlikely name of “Miss Deep Freeze.” And she told them about her meeting with agent Louis Shurr and Columbia executive Max Arnow, who arranged the screen test that led to a long-term contract.

Some reporters asked foolish questions. “Do you bite your fingernails, Miss Novak?” To which Kim good-naturedly replied, “No, I’m the nervous type, but I’m not that nervous. Anyway, as I told you, I’m on a diet.”

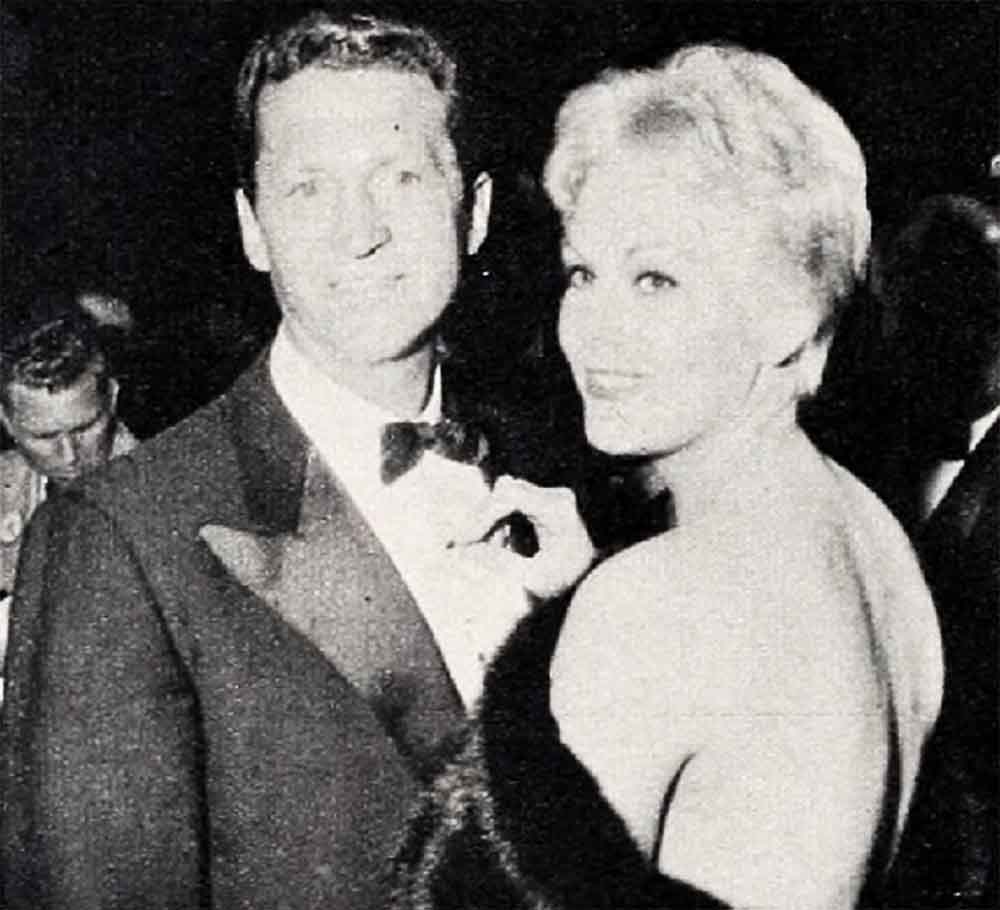

Often there were questions about her romance with Mac Krim. He has been her constant escort for months, and has told anyone who cared to ask, “She’s my best girl.” But Kim had learned to shrug off romance questions with noncommittal answers.

On a few occasions she got the phony oh-the-wonder-of-it-all treatment. One inquiry went like this: “How does it feel to wake up in the morning and look in the mirror and be so beautiful?” This drew a very short reply. Kim was infuriated. “I hate being patronized that way!” she said later. “I really resent it when they use that dumb-blond approach. It’s not very flattering.”

One morning, an interview was reduced to a shambles by an uninvited guest. Kim looked very fetching in a light blue sweater and black toreador pants as she sat in a big chair, relaxed and happy, with her bare feet tucked up under her. Then suddenly she leaped into the air.

“E-e-e-k!” she exclaimed, dancing on the table top. “A mouse!”

Muriel Roberts and the interviewer tried to treat the incident calmly. They had seen no rodents, they stoutly maintained. Possibly it was all Kim’s imagination.

Kim refused to be shushed. “He was right there!” she pointed frantically. “He was tiptoeing under that chair and waggling his ears! And he snickered at me!”

An assistant manager was summoned. “This is ridiculous,” he proclaimed. “You must be mistaken. In all my years of service at the Sherry-Netherlands we have never had a mouse.”

“Well, you’ve got one now,” Kim stated flatly. “So don’t just stand there. Call out the Marines!”

Some bellboys, plus several members of the engineering department next came to the rescue. They carried mops, brooms, rolled-up newspapers, pails of sand and ammonia bombs. They deployed their forces and the suite was scrutinized inch by inch. After a long interval of waiting and suspense, a thudding Pow! emanated from one of the bathrooms.

The assistant manager appeared. “The crisis has been met, Miss Novak,” he announced. “The enemy has been destroyed. He was about two inches long. You may come down now and relax.”

And so the day was won. Everyone departed—including the interviewer. He didn’t get much of a story that morning, unless he wrote one about, “The Mouse Who Came to Breakfast with Kim Novak.”

That incident, of course, was an exception. Most interviews were quite orderly and successful, and most of the reporters were serious, hard-working people who wanted to write provocative stories about this bright, new, Hollywood star. And Kim gave them their stories.

“Look,” she told them. ‘I’m still new at all this. It’s sort of bewildering at times. I like to talk about myself, but it’s still not too easy to go into intimate details about some of the unhappy phases of my childhood. I was really a scared kid. I had all the frustrations and insecurities in the book. I thought I was unattractive, and I guess I was. And when the other kids taunted and mocked me it hurt. The hurt went deep, and I didn’t get over it easily.

“Oh, I don’t think I have any emotional blocks about this. Not really. Possibly I do have some scars. But they’re pretty well healed over. And,” she grinned, “you probably can’t notice them when I’m all dressed up and have my make-up on. Because I’ve grown up. I’ve matured, mentally as well as physically. I’ve learned to cope with my problems and live with them to the extent that they no longer bother me. I’ve triumphed over them, if you want to use such an all-inclusive phrase.

“But at the same time,” Kim added, “the good things haven’t been so easy to handle. So, in effect, the good things have become problems. And if that sounds like a paradox, it is.”

Kim grinned, but her eyes revealed a thin veil of uncertainty. “Am I getting through to you? I hope so. Anyway, I’ll keep trying.

“You see, it all happened so fast. One minute I was on the outside looking in. I used to read magazine stories about Hollywood stars, and wonder how it would be to have a story written about me. I did some powerful wishing in those days, but still it all seemed pretty remote. You know how a kid will wish for a pony or an expensive dollhouse without ever really expecting the wish to come true? Well, that’s the way it was with me and Hollywood. Then—boing! It happened. And here we are.”

She made a funny face. “But where are we? On a sort of perpetual merry-go-round, with everything flashing by so fast it makes me a little dizzy. The faces of the people watching me are kind of blurry, too. But there it is just the same, with the brass ring hanging there, sort of tantalizing, waiting to be grabbed, and me hanging on for dear life, giving myself a constant fight talk. ‘Don’t lose your grip, girl!’ I keep telling myself. ‘Don’t fall off the merry-go-round!’ ”

At this point, Kim paused to catch her breath. If the interviewer had more questions, she tried to give the answers.

“No, I don’t smoke or drink. It’s not a moral question; it’s just because I don’t enjoy these things. Oh, I take a few sips of sparkling wine or champagne on very special occasions, but I don’t make a habit of it.

“And I’ve tried smoking. When I was at Wright Junior College in Chicago, I belonged to a sorority, Alpha Beta Mu, which had very strict rules. The freshman pledges couldn’t wear lipstick or have dates with boys or smoke. Naturally this was a challenge I couldn’t ignore, so I bummed a cigarette—from one of the other pledges. After I lighted it, I took a deep inhale, just like the boys did. For about a minute I felt pretty smart. Then I began to get dizzy and the room started going around. Lordy, was I sick! Then, on top of that, they caught me. And since I had broken the rules, they paddled me. They also pointed out that since I didn’t really smoke, this was an extra belligerency on my part. So they paddled me some more, and a whole lot harder. Ever since then I have never had any desire to smoke.”

After five crowded weeks in New York, Kim headed west again for Hollywood. She looked forward to her quiet room at the Studio Club and a chance to relax and catch her breath. But it didn’t work out that way. She had barely unpacked her bag when the phone began to ring. The studio had filled her days with appointments for this, that and a dozen other things.

Kim fought back some quick, bright tears and said, “Okay, I’ll be there. Yes, I’ll be on time.” So the music was still playing, and the merry-go-round didn’t stop for even a moment.

On this very morning she had kept her appointments with the hairdresser, the head of wardrobe, and her publicity luncheon at the Naples Cafe. The magazine writer who showed up was tall, with a long nose and quizzical eyebrows.

“I don’t really have a story angle, Kim,” he said. “But our readers are tremendously interested in you and your career. They want to know what’s going on in your life, what’s happening to you.”

Kim nodded brightly and smiled. “That’s wonderful! I’m awfully flattered by all this, and I’ll try to give you any kind of story you want. But I think you’ll have to dig for this one. At this point I’m a little talked out.”

“Do you think you have changed since you came to Hollywood?”

“Have I changed?” Kim’s eyes widened. “I don’t have to hesitate for the answer to that one. I’ve changed plenty. That is, I’ve learned plenty. I think I’ve grown and developed. And I now know quite a lot about emotions and how to portray them on the screen—which is the essence of all acting. At the same time, I’ve learned how to control my own personal emotions. Not too long ago I was upset by the least little thing. I used to fly all apart. But now I’ve learned to take my problems in stride. I know that I can’t always have things my own way, and so I ad just. I swim with the stream when it seems advisable and sensible. And life is happier that way.

“I’m still not perfect. I’m miles and miles away from perfection. But I’ve taken several steps in the right direction and that’s a change, a definite form of progress for me.

“But I’m still scared part of the time. Maybe that’ll go away someday. Maybe I’ll be able to go to Romanoff’s for lunch and sweep down those stairs with everyone turning around to look at me and not be scared. But maybe not. It could be that being scared is part of living—and, of course, a part of dying. But I try not to think of things like that.

“I remember once reading about Helen Hayes, who says she is always scared just before she goes on for a performance. And after all these years. So if a great actress like Helen Hayes is scared in front of an audience, I guess it’s nothing for me to be ashamed of.”

Kim took a drink of water. Her eyes were serious.

“A few years ago, I used to wonder just where I was supposed to fit in, in this world. I’m inclined to be introspective. I used to search my thoughts and ask myself, ‘Who are you? What are you supposed to be? Why are you here?’ And of course there was only a big silence after that, because I didn’t have any of the answers. Then I came to Hollywood, and I found something to work for.

“At first I was only a face in front of the camera and a body that wore clothes. Somehow the face was photogenic; the camera was kind to it. And so I made a couple of pictures and got along pretty well.

“But then I began to discover that there was a real person behind that face. Someone I hadn’t really known before. I discovered a new capacity within myself. It was like finding a brand-new personality. A whole new world opened up to me. It was wonderful!

“Since then so many people have been kind to me and helped me. I couldn’t have done anything without them. My last three pictures, ‘Picnic,’ ‘The Man with the Golden Arm,’ and ‘The Eddie Duchin Story,’ have been good ones. This has helped me tremendously. My career, as they say out here, has zoomed. I have been very lucky, no doubt of that.”

“What about the future?” the writer asked.

Kim shrugged. “The future is . . . well, the future. I have plans, yes. I want to travel and see all of Europe. And of course I want more good movie roles. I want to improve as an actress. But I don’t want to look too far ahead. This new person I have discovered within me is very exciting. And so I just want to live each day as it happens.”

“What about love? What about you and Mac Krim?”

Kim’s eyes widened again. “I don’t know. I’ve been too busy to think about it.”

“Will you marry him? Next week? Next month?”

“I can’t say,” Kim said. “I really don’t know. Too many things are happening right now.”

After that, Kim’s day went off according to her schedule. This included a photo sitting, dental appointment, French lesson, driving lesson, and four hours in Batomi Schneider’s drama class.

Bone-tired, Kim was in bed soon after midnight. She stretched out deliciously, her thoughts filled with the events of the day. She thought about her luncheon interview and the writer with the quizzical eyebrows who didn’t have an angle for his story. “Maybe,” she thought, “he could call it ‘Girl on a Merry-GoRound.’ ”

She also thought about Mac Krim, and of the questions the writer had asked about him. That suggested another possible title: “Is Kim Too Busy for Love?”

“Is she?” Kim asked herself. She smiled, because she knew she didn’t yet have the answer to that one. Then, with the smile on her lips, she closed her eyes and went sound asleep.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1956