These Are The Days Of Gregory Peck

From the day of his birth, Gregory Peck was marked out for an important destiny—either that or abject failure—for there never was a moment when he wasn’t at complete variance with the average child. He wasn’t a pretty baby, but he was a long one, long torso-ed, long limbed, with great, dark eyes and a buzz of hair that promised to be very dark, and strong too.

His father wanted him, his first born, to be named Gregory Junior, but his mother had another idea, so they compromised and named him Eldred Gregory, a name which he disliked from the time he was old enough to be aware of it. The compromise was characteristic of the life his parents lived together. They were romantically in love—but their minds were always at war. They quarreled and made up, quarreled and finally separated. Such a domestic atmosphere does things to a child, who is its inevitable storm center. It did things to young Eldred.

Gregory Peck the second was born in La Jolla, California, on April 5, 1916, and today, as the whole world knows, he is the fastest rising male star in movies with four of the major studios owning a share of him.

His first picture, “Days Of Glory,” for Casey Robinson and RKO, turned out to be not so hot at the box office, though he was personally a triumph; his second, “Keys Of The Kingdom” for Twentieth Century-Fox was mostly a critical success and Greg was magnificent in it. However, his third, “Valley Of Decision” for M-G-M, is a smash, and this too is said of “Spellbound” under the Selznick banner, though the film has not been generally released as yet. Right now, so great is the demand for his services, he is in two productions at once, “Duel In The Sun” and “The Yearling.”

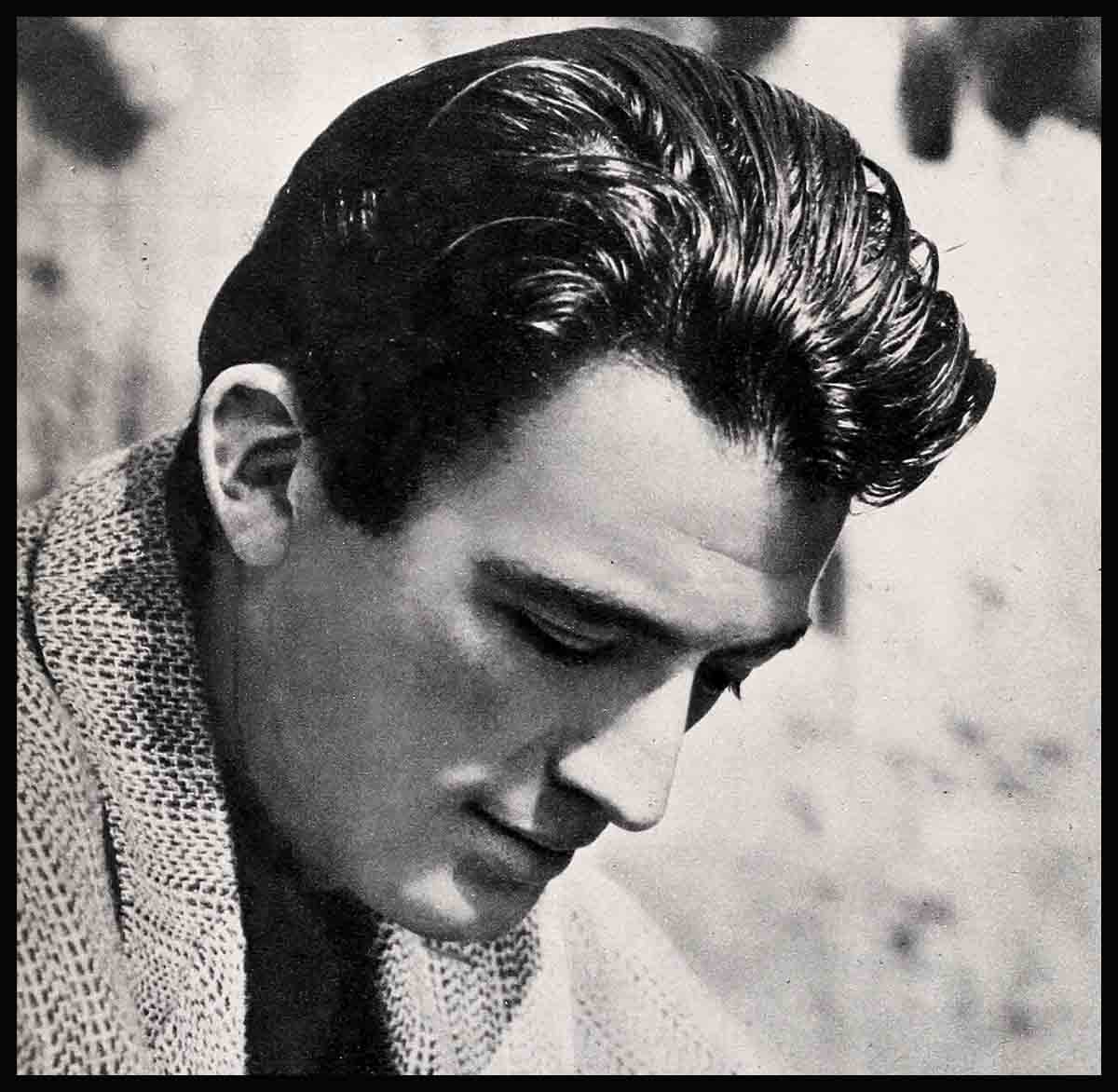

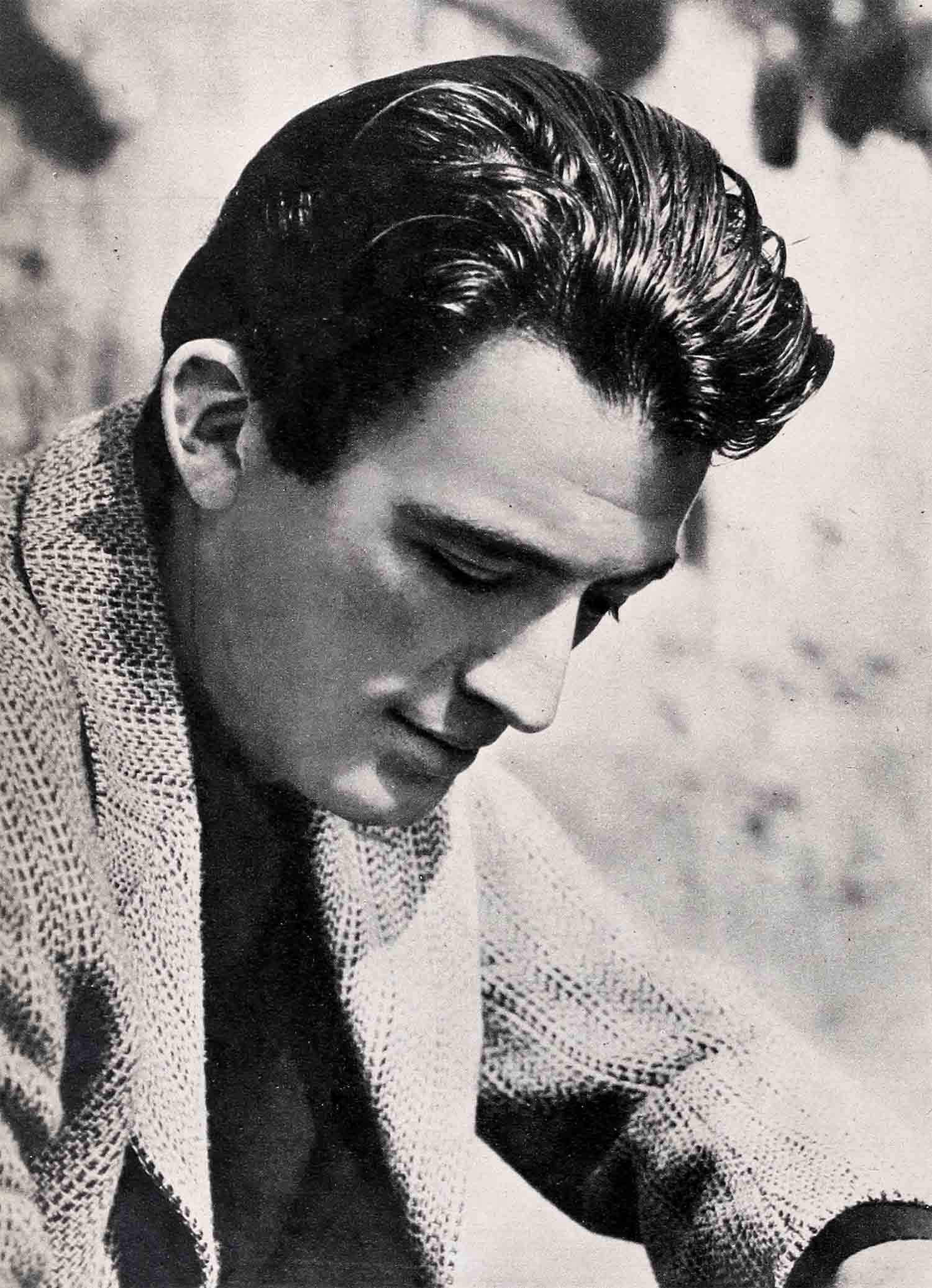

Gregory Peck is, at twenty-nine, that rarest of combinations, a truly great actor who is also a handsome, humorous, intelligent, sensitive human being. He is even now—with fame swarming all over him, with people flattering him, the press adoring him, studios catering to him, and money pouring in to him—still an unaffected gentleman. For that reason there are those in Hollywood who label him very simple and—because of his angular face—Lincoln-esque.

He is nothing of the kind. He is as subtly complex as the mechanism of a ninety-day water clock. He is a great reader of heavy books but he also dotes upon playing all sports, his favorites being tennis and swimming. He is a jive bomber who craves his music hot and dirty, but who also adores the Brahms First Symphony. He is enormously excited at the prospect of all the money he is about to make, but his chief concern is giving the finest performances possible. Strange women now throw themselves at his head, but he is blissfully married, has one son and would like to become the father of five more.

How he got this way may very well rest upon a pair of buttoned shoes—and his father.

His father was a romantic and an adventurer and he expressed these moods in a very American way. He pioneered. He came out to California from the Middle West in 1906 and decided—even though he didn’t know a soul—to go into business for himself. Admittedly the Indians were out of California by that time, but there still wasn’t a great deal else, barring orange and palm trees, except in the city of San Francisco. Greg Peck looked that over and decided it was too crowded for what he wanted. He finally found the little town of La Jolla, on San Diego’s outskirts, which sits atop a cliff above a little cove of the Pacific, Palms line its waterfront and its few streets. Everybody has a garden. Everybody smiles.

There in 1906, Gregory Peck opened a drugstore. He opened it, not to make money, but to make a living. There’s a big difference f there. He was a handsome, intelligent young bachelor in a romantic little town, which meant that his life was one long bliss of moonlight and rosy girls until one day in 1915, a very pretty young thing named Bernice Ayres from the Middle West came along. She was little, and the local belles could have killed her, for smiling and vivacious Greg Peck fell in love with her instantly. They were wed almost at once too, and in 1916 their baby came.

Greg’s earliest memory is sitting outside his house, in the hot California sunshine under a palm tree, a thin, small boy of two, playing with his white dog and white cat. He loved those pets in the intense way that only a shy and lonely child can—and he was shy and lonely all his life until he was sixteen. Enter then a siren with black hair and green-blue eyes who got him over all that.

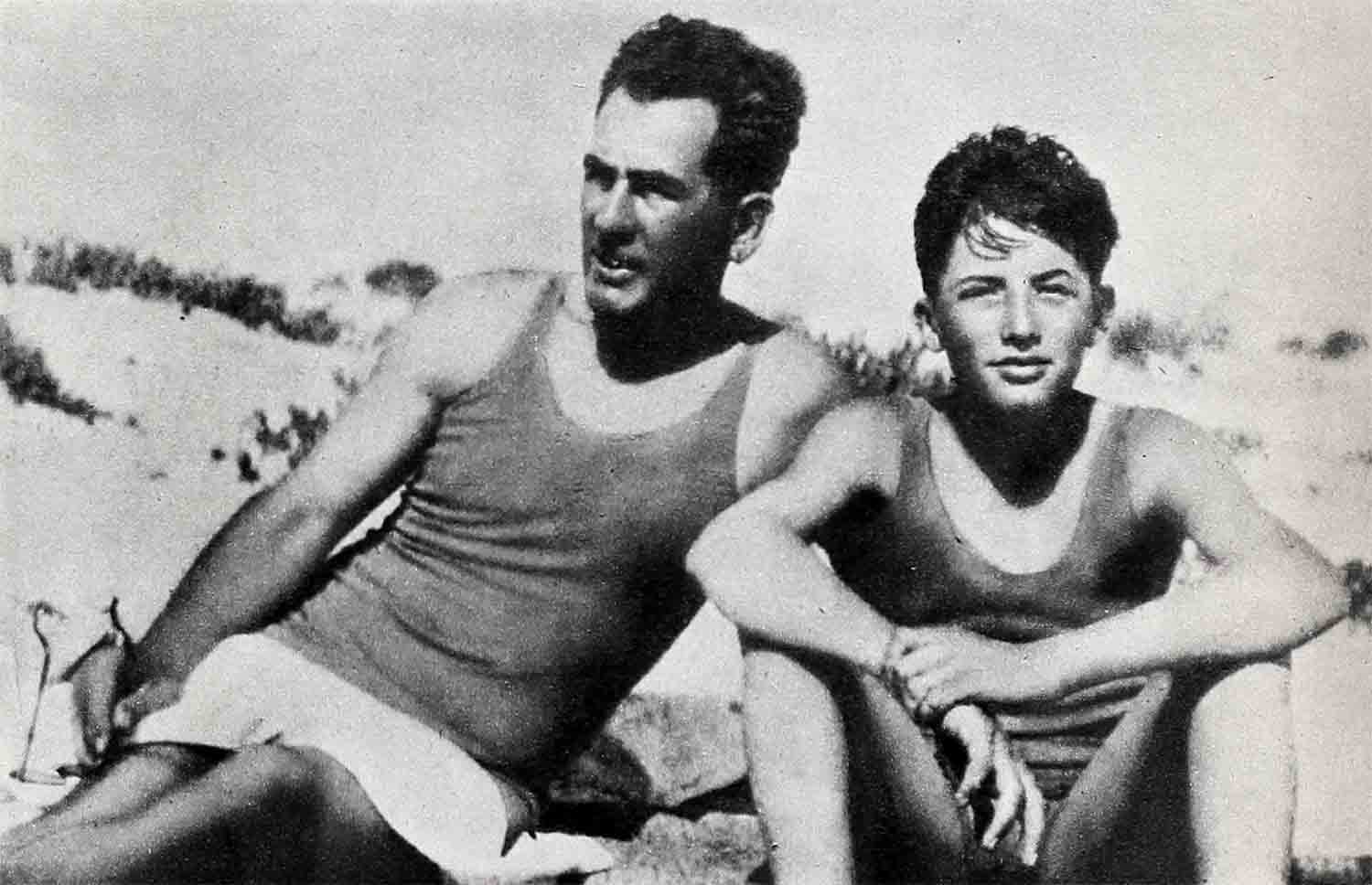

He was only five when his parents separated and his mother’s mother came to La Jolla to take care of him. She was a very kind grandmother but she understood very little about California small boys. On the other hand, his father did—or at least, he understood this one. Father and son became a great team. Grandma would pack them up a lunch in paper bags and to the beach they’d go, to lie all day in the sun, “from seven to seven” Greg says, to swim, to hunt for clams and commune with nature and one another.

Yet it was one of these beach excursions that almost cost him his life. He and some neighborhood lads were diving for abalone, lurking far down in the ocean bed. Greg took an iron bar, dove off with such force that he went down for more than ten feet. There he saw the treasure he was seeking, but as he pushed his bar under a big rock, the bar slipped. He went to retrieve it and the rock settled firmly down upon his hand. He fought and struggled to get loose. It was several minutes—a lifetime under water—before the kids on the surface noticed he was missing. They dove frantically down for him, freed him and brought him up, but it was more than an hour before the life guard was able to revive him.

His other most frightening adventure was concerned with water too, though he’s still a water baby and every free moment he has, he hies himself to a beach. He was thirteen, and he and his father had gone duck hunting. They were more than a quarter of a mile from the shore of the lake when Greg, moving the gun, heard it go off and to his horror saw that he had shot his father in the shoulder.

“Dad was so wonderful,” Greg says. “He sat there, trying to smile at me, trying to hold his shoulder together, while the blood ran through his fingers, and I rowed frantically. I was very light and very thin, and the boat was very heavy. It was a long time before I could get us to shore, find a telephone and get an ambulance.

“They took Dad to a hospital immediately and operated. He was two hours on the operating table, while I waited outside, frozen with terror. The first thing Dad did when he came to was to look for me and smile with complete understanding and forgiveness. I can never forget the release of that moment, the sense of freedom and devotion that swept over me.”

If, through this episode, his father brought home to the boy the meaning of paternal love, his grandmother, very innocently, taught him how to fight. Grandma bought a pair of cloth-topped, buttoned shoes. To her, those shoes were something dashing. To Greg, they were horrors, since no other boy in La Jolla wore anything of the sort. Since they were the only real shoes he had, he begged Grandma to buy him others. But Grandma refused to waste money on another pair and she wouldn’t let him go to school in sneakers.

His father slyly helped by getting him a bicycle. What Greg did, then, was to take off the shoes, as soon as he got out of sight of the house, bike in his bare feet, put the shoes on again at school, knowing that he’d have to fight his way through the recess period because of them. At least they taught him to be good with his fists.

In due time he decided to enroll in the University of California at Berkeley to study medicine. But the black-haired, green-blue-eyed siren entered here.

Let’s call her Mary. She had, according to Mr. Peck’s testimony, that lovely hair and those green-blue eyes, and she could do anything. So far as our hero was concerned, she was Dame Cupid. He forgot everything. His class marks slid. Sports went by the board. The only thing he wanted on earth was to marry her, but he was just seventeen and didn’t have a dime in the world.

“I became a truck driver for love,” he says. By that, he means that he quit school, got a job at a colossal $120 a month and began making romantic plans.

Eighteen months went by. He and Mary decided they couldn’t wait any longer. One night they hopped into Greg’s car and headed toward Las Vegas, some two hundred miles distant. They had covered five when they began to waver. By the time they had gone another five, they knew they were too young to face the responsibilities of matrimony. They turned back. Next day Greg quit his job, started to bone like mad and made U. of C. in the fall, at which point he dropped the hated Eldred and became henceforth Gregory Peck Jr.

Two pals of his from La Jolla enrolled in the same class. They drove up to Berkeley together, roomed together, went tc classes together and did janitor work together as a means of paying their rent. The other two boys were, Mr. Peck says, “smart operators,” and Greg learned fast.

“We got a parking lot to run on Saturdays. We did all right with that normally, but when the football season came, we really sliced it. Charged a dollar for every car we parked then, blandly telling our customers that we were right across the campus from the football field. That was true except that we were at one end of the campus and the field was at the other, a mile away.”

All this wealth began to enable Greg to take occasional weekends off. He bought a roadster and cut classes late Fridays, drove all night to San Diego, got there Saturday morning, started back Sunday night and made classes again on Monday. That was a matter of 1300 miles for two days with one girl. That, also, was love. He did it week after week.

But, as in high school, his studies began suffering. “I went at my medical career most half-heartedly,” Greg says. “I wasn’t yet on the right track and in a dim way I knew it. I dropped pre-med and switched to English. I went in for crew and this time I made it. When I was sent East to row in the regatta at Poughkeepsie, I thought I had reached a crown in human achievement. Still, I knew there was no way I could make a living at that. By this time it was 1938. I was twenty-two. I felt it was time for me to get into some kind of groove.”

It was entirely by accident that he got into acting. One night a buddy asked him if he wouldn’t like to fill in the remaining scrap of his free time by taking a role in a play that was being given on the campus. A tall character was needed for the role of the first mate in “Moby Dick.” Greg went on in the part and the magic of the theater captured him.

“I was very lousy in that first part and I knew it,” Greg says, “yet I’ve never had such a moment of complete, utter happiness before or since. It was a terrifying experience. I hadn’t been able to eat or sleep for the three days preceding it. Once on stage, however, and I was instantly freed of all my shyness and inhibitions. I saw that audience looking up at me and I could have done anything, for in that moment I got rid of Gregory Peck, the guy who was so unsure of himself, and became, to myself, a veritable wonder man. From that instant on I wanted to do nothing whatsoever but act. In one sense, I confess it’s still true.

After that, I was aware of nothing save theater, theater, theater. Summer came. I was graduated. I just wanted to keep on acting, anywhere, in anything. I felt prepared to invade Broadway. I did invade Broadway. None of the buildings trembled with delight as I passed by. No managers greeted me with open arms. I finally used the letter my stepfather had given me to a friend of his who owned part of a concession at the World’s Fair. I went over to him, presented the letter and got the job as assistant barker at the towering sum of $25 weekly. I thought I could eat on that. I was, at least, glad to write the folks, who had been so sympathetic and understanding, letting me waste all that time in “finding myself” that I was finally self-supporting in a big way in a big city. Little did I realize how expensive was everything at the World’s Fair or in all New York or how completely my appetite was to go ahead of my earnings.”

When the World’s Fair closed, Greg nearly starved. Autumn came and he was lonely. Winter came, and he got no parts in Broadway productions. But he never lost the bright vision in which he believed.

“One night in winter,” he says, “when I had no work and scarcely a dime, I went up to the roof of the highest of the Radio City buildings and looked down over Manhattan. It was just getting dark and the lights began flashing on, all over town. It began to snow, great flakes falling, magically through the giant spotlights round Rockefeller Center. I could see millions of tiny fast moving figures below. All going somewhere, all trying to attain their private dreams. It was the most humbling sight, and yet the most exhilarating, for these others, too, were lonely and fighting for existence. Anyone, as one individual, could be lost among them, and yet anyone, this being America, could, with a little fighting for it, attain his dream.

“I came down from that tower so happy I didn’t give a damn if I was hungry. The fight was up to me and that knowledge was exciting. I knew beyond all arguing that just around some magic corner, something waited for me.”

Excellent fortune was waiting for him. But even good fortune, when it came, stayed true to the Peck pattern and he had to work hard to attain the rewards it offered.

Finally, of all things, he won a scholarship for dramatic training at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Greg was surprised, as only a Westerner can be, to find this tucked away in the New York slums. Nonetheless, it has one of the most artistic, stimulating, truly creative atmospheres any young player could come upon. For two years Greg learned invaluable technique there. As a result, he got another scholarship at the Barter Theatre in Abington, Virginia.

The Barter is an amazing little theater where customers barter whatever they wish—vegetables, chickens, in place of cash, for tickets. But its artistic standards are very high and here Guthrie McClintic, the intelligent, wily and famous producer-husband of that first lady of the legitimate stage, Katharine Cornell, saw him and signed him for a season with his wife.

He was such an excited young actor when he joined the tour in Philadelphia that in order to conceal his exuberance, he went around, when not actually rehearsing, with his nose hid in a book. He was so in awe of Miss Cornell and the whole company that he hardly dared glance up. The company was doing a tour in a revival of “The Doctor’s Dilemma.”

Then one memorable night on the station platform in Philadelphia Greg heard a girl’s laugh ring out. It was the merriest laugh he had ever heard and he looked up and met a pair of laughing blue eyes, eyes that belonged to a small, blonde girl standing beside Miss Cornell—the prettiest, gayest, most provocative girl he had ever observed in his life—and despite his diffident-appearing manner, Greg carefully observed every girl he saw.

The blonde girl seemed to be with the Cornell Company, yet Greg knew, the moment he glanced at her, that she wasn’t an actress. He dropped his eyes back to his book, but his heart sank as he heard her saying something about her fiance.

He didn’t want her to have a fiance. If a girl like that had to have a fiance, he thought he should be someone dignified and protective like himself.

Five months later the blonde girl did have a fiance like him. In fact, it was he. But that is getting ahead of our story, which would be a pity, for you never did hear the story of a cuter courtship.

For example, one of the things Greg told small blonde Greta was that he was a full-blooded Indian. He told her about the scalpings his grandfather did regularly. But wait and watch for it next month in this very same place.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1945