Lover Boy

Say what you want to, I think Elvis Presley will be the 1957 Rudolph Valentino or John Gilbert.

I mean, he can be a colossal screen lover. And this boy is no dope. He’s determined to accomplish what he sets out to do, whether it’s singing, acting or making a girl.

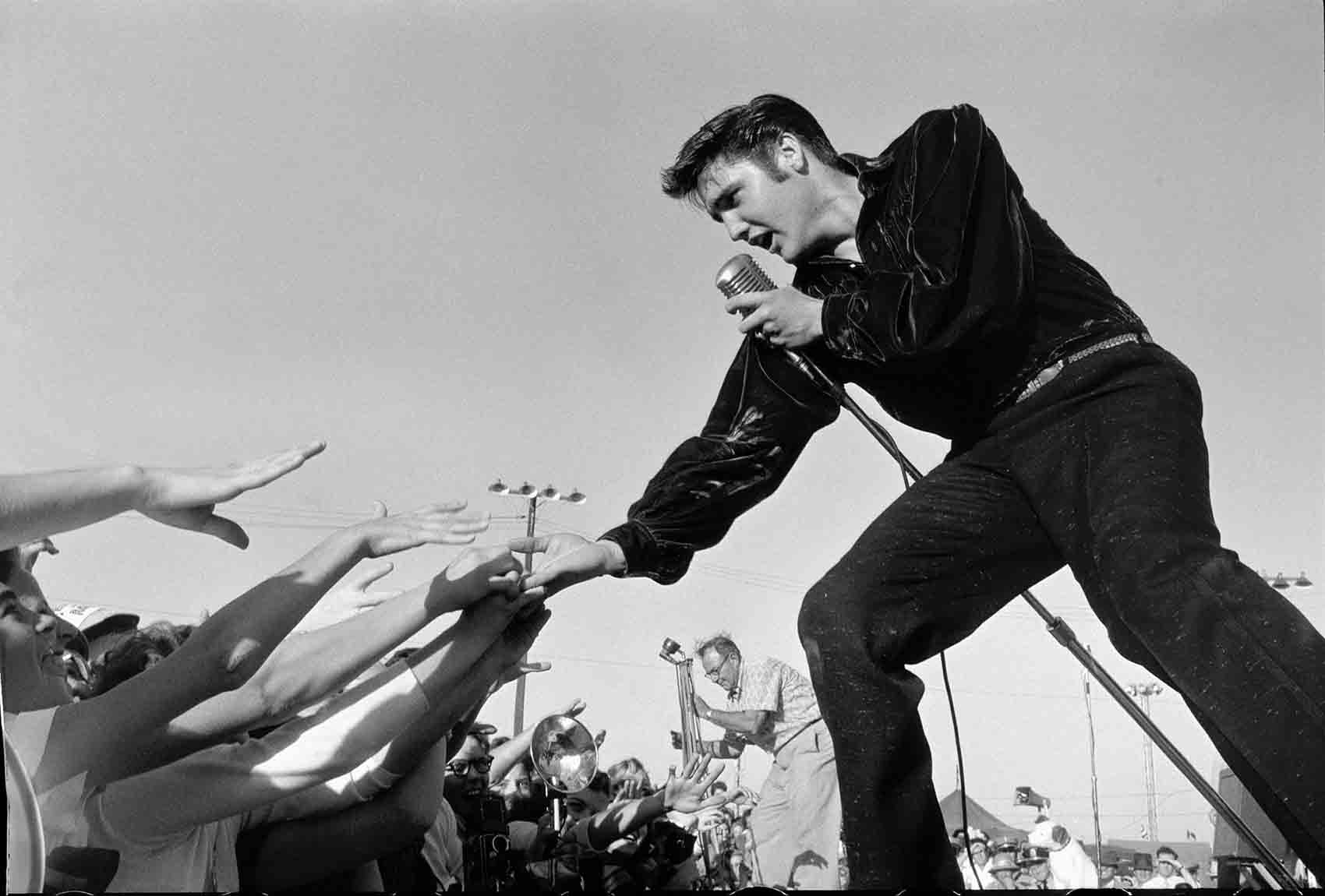

It’s doubtful if the Valentino worshipers adored Rudolph any more than the Presley fans love Elvis. One day in Hollywood some fifteen-year-old girls, with the name “Elvis Presley” stitched on their toreador pants legs and guitars on the backs of their sweaters, waited for him until he went to lunch.

AUDIO BOOK

Elvis asked them to come into a luncheonette with him, and he bought them sandwiches.

“Of course, we couldn’t eat. We just watched,” one little girl said. The sandwiches became souvenirs.

There’s a fad in California for hanging knitted dice to swing behind an auto windshield, as many people hang baby shoes.

“We’ve seen some pictures of your Cadillacs, and they look awfully bare,” one fan club wrote to Elvis. “We want to present you with some knitted dice for each one of your Cadillacs. We have a blue set for the blue Cadillac, a white set for the white Cadillac, and a pink-and-white for the pink-and-white Cadillac.”

Semo of the fans are too worshipful. Elvis thinks a girl in Kansas City made away with more Elvis Presley mementoes than anybody else ever has or ever will.

“I think I know who it is,” he said.

“I think she got my red sport coat and red shirt off the stage and also my gittar,” he added. “That gittar cost $250, which is a lot of money for a gittar. The one I got now cost about $375.”

The Elvis Presley fans also write angry and sometimes threatening letters to newspapermen who criticize him. A Minneapolis radio station decided not to play any of his records. It got some letters promising vengeance. A rock was thrown through the station’s front window. An inscription on the rock said, “I’m a teenager. You play Elvis Presley records or we tear up the town.”

Elvis, of course, doesn’t encourage or approve of this conduct. But the fans get out of hand.

“This success of mine means too much to me to do anything to foul it up,” he said. “For example, I’ve never touched any sort of alcohol. It doesn’t pay off in this business. Anyway, I wouldn’t have time to drink. Five or six hours a night is all the sleep I get, which isn’t enough.

When I saw Elvis in Hollywood, he had none of his Cadillacs with him, nor his Messerschmidt, either.

“My daddy’s keeping them up for me down in Memphis,” he said. “He helps me with the mail, too.” Elvis pronounced help “hep” in the enchanting way that most Southerners do.

One day, when Elvis was staying at Hollywood’s Hotel Knickerbocker, his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, came in to find 230 phone messages waiting for him.

The Colonel—he got his colonelcy from the Governors of Tennessee and Mississippi—had the tedious job of sorting out the messages to find which were calls from people who weren’t teen-age fans.

Despite all this attention and worship, Elvis continues to call almost everybody older than himself either “Mister” or “Sir” or “Ma’am.” Sometimes the “Sir” becomes a soft, pleasing “Suh.”

“What are you going to do with all your money?” I asked him.

Color photos by Nelson Tiffany

“Suh,” he answered, “I haven’t got my mind settled on that. The Colonel is going to hep me decide that. I don’t know too much about that sort of stuff.”

But Elvis had already bought a home for his parents in Tennessee and was also giving them a trip to Hollywood. Not that he expected he’d be able to spend much time at the home in Memphis.

“I’ve been mostly on the road for two years,” he said. “You name it and I’ve been there.”

Elvis wasn’t easy to pin down on the subject of girls. There was a pretty little blonde named Jan Storey in the chorus at Ciro’s who suddenly became a celebrity because Elvis dropped around to see her.

“Did you date her?” I asked him.

“Yeah, I’ve been datin’ a lot of girls,” replied Elvis, evasively.

He surely makes no secret of his interest in the opposite sex. Curiously enough, he met a girl in Texas whose first name is also Elvis. But he didn’t get to know her well enough to remember her last name.

“Where did you get the name Elvis?” I asked him.

“It was my daddy’s middle name. Where he got it, I don’t know,” he said. He’s an only child. “There’s just Daddy and Mother and me,” he says.

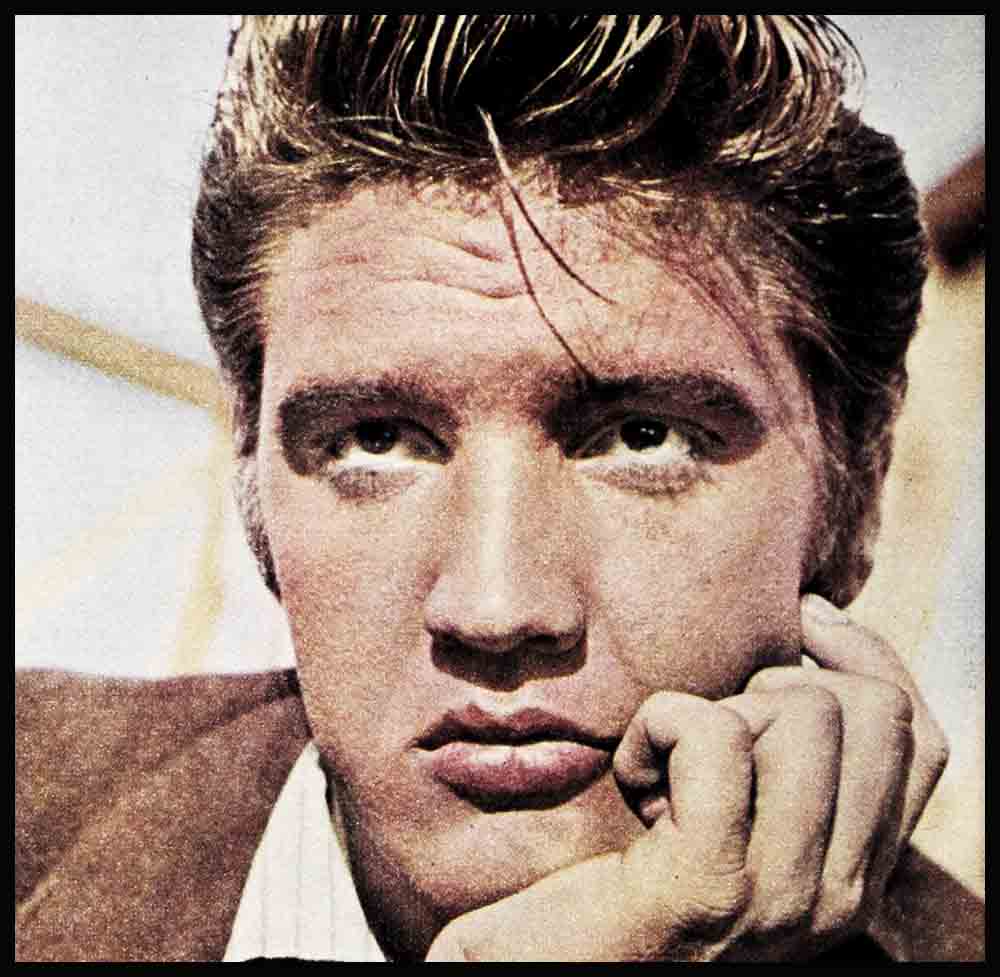

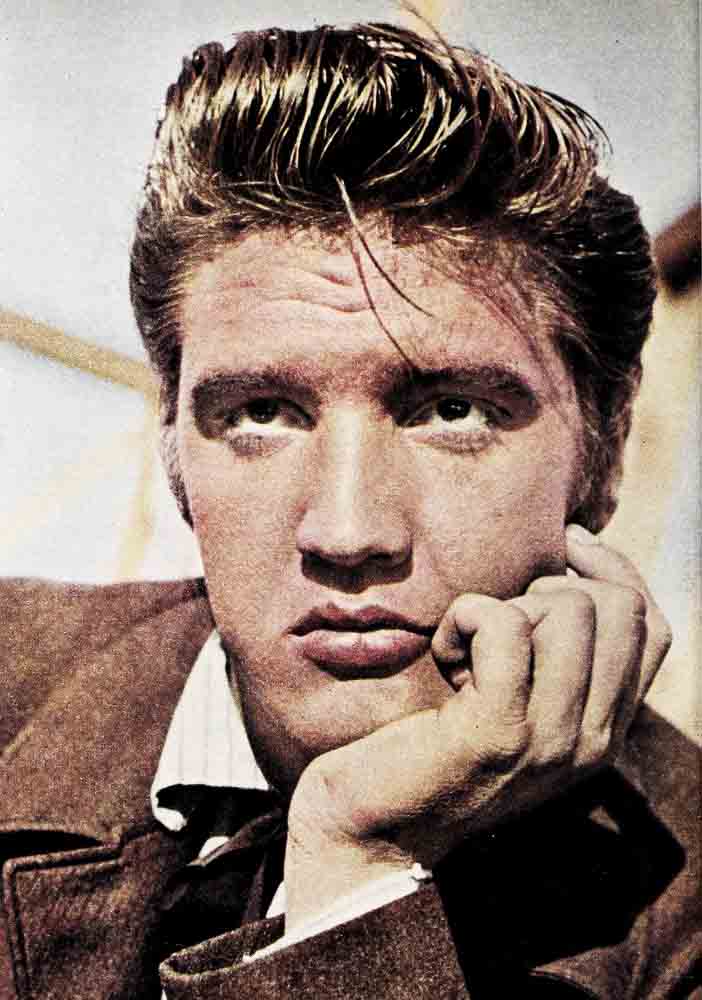

Presley’s fans are as much impressed with his looks as his voice. He has a sort of dark, sooty look under the eyelids that gives him a dramatic appearance. This is not make-up. It’s just there.

“How did you get sideburns?” I asked.

“I always figured as a little boy that when I grew up I wanted to have sideburns,” he answered. “Soon as I could, I got ’em.”

At one point, however, when he didn’t have complete confidence in himself as yet, he abandoned them. Then he came back to them. I asked a 20th Century-Fox spokesman whether they were contemplating any changes in Elvis’ looks.

“Say,” replied this spokesman, “we wouldn’t dare to change his looks or to touch those sideburns. We’d cause riots.”

“Why are you such a successful singer?” I asked him at the time he was getting his fourth gold record, presented to mark sales of over a million of one of his discs.

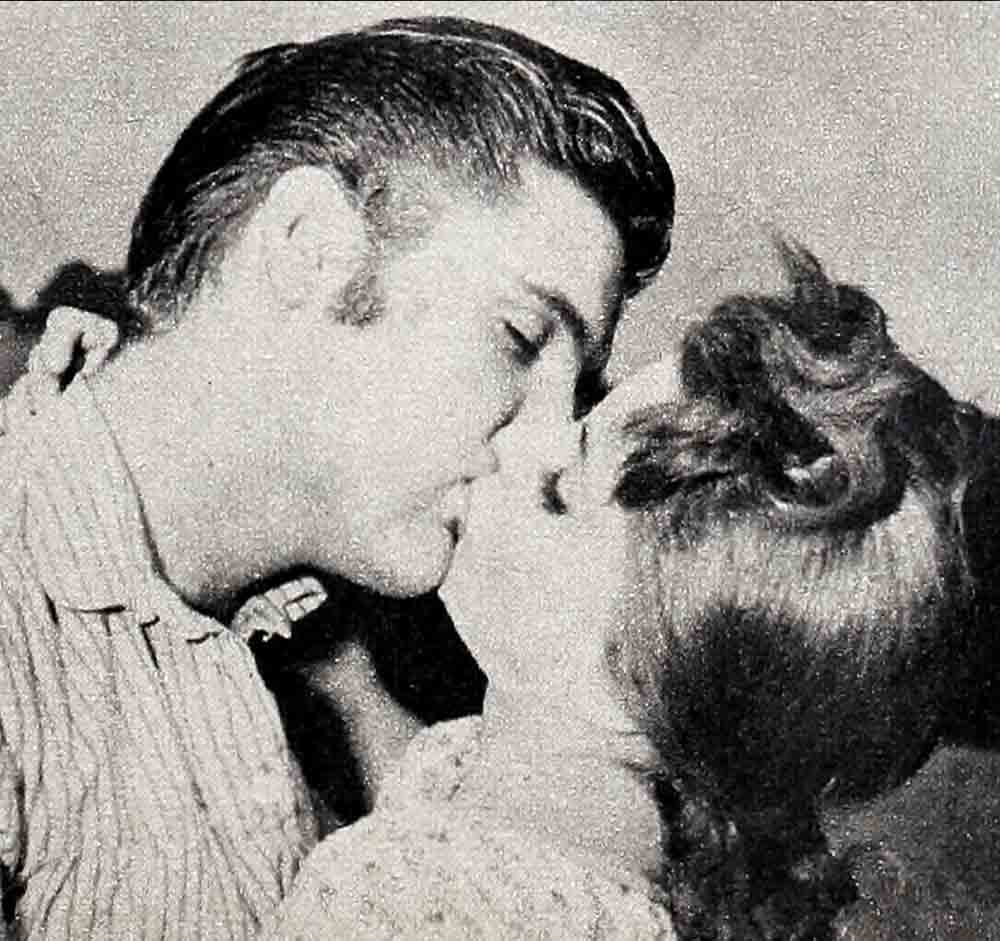

“Maybe it’s just because I enjoy it so much myself,” he said. “I put my whole heart into it. Maybe people can see that.” He takes the same attitude toward his acting, including the love scenes.

“I always wanted to sing,” he said very seriously, “but I didn’t think I could make it. I used to go to all-night singin’s in Memphis. We’d sing very beautiful spirituals and hymns all night long. Some of the songs had beats like a regular rock ’n’ roll song. That music doesn’t hurt anybody, and it makes you feel good. I used to get chills up and down my spine listenin’ to some of those songs.

“But I don’t know a note of music. Some people have warned me not to learn any. They say if I ever learn how to sing good, I’ll be out of business.

“I got my first gittar when I was about eleven,” he remembered. His family was still living in Tupelo, Mississippi, Elvis’ birthplace, then. “My daddy was a common laborer,” he said. “He didn’t have any trade, just like I didn’t have.”

Elvis was about thirteen when the Presleys moved to Memphis. He sang a lot at the First Assembly of God Church. In high school he never tried to get into any student plays. When he got out of high school, he found a job driving a truck.

“I was happy,” he told me. “I didn’t have any money or anything. But I was datin’ once in a while.”

At the time other youngsters his age were having cheap recordings made of their voices, just for the fun of it. and Elvis did, too—but not for fun. When Sam Phillips, a local record-maker, didn’t immediately announce that he was a genius, Elvis became discouraged.

“I didn’t even pick up my gittar for a year and a half,” he said. “I just drove my truck.

“Well, one day Sam Phillips called. He said, ‘I have a song I’d like you to work on. Can you be here by three o’clock?’ I was there by the time he hung up the phone.”

Sam Phillips had actually been greatly impressed by Elvis the first time he’d heard him. He proceeded to make Elvis’ first record, “That’s all Right.” Very soon after it had started to sell, Elvis appeared before 4,000 people in Memphis’ outdoor Overton Park, as part of a big package show. He was paid $200.

“I was real scared, because I’d never sung in front of a crowd before anywhere except church,” Elvis said. “I hid when they played my record.”

Elvis went on the radio. He had a habit of jiggling his leg with the rhythm. That attracted some attention.

“I was still scared,” he told me. “I thought people’d laugh at me. Some did and some are still laughing. Then there are people who say what I do is wrong, but Eve never done anything anyone could really call wrong. My mommy wouldn’t let me.”

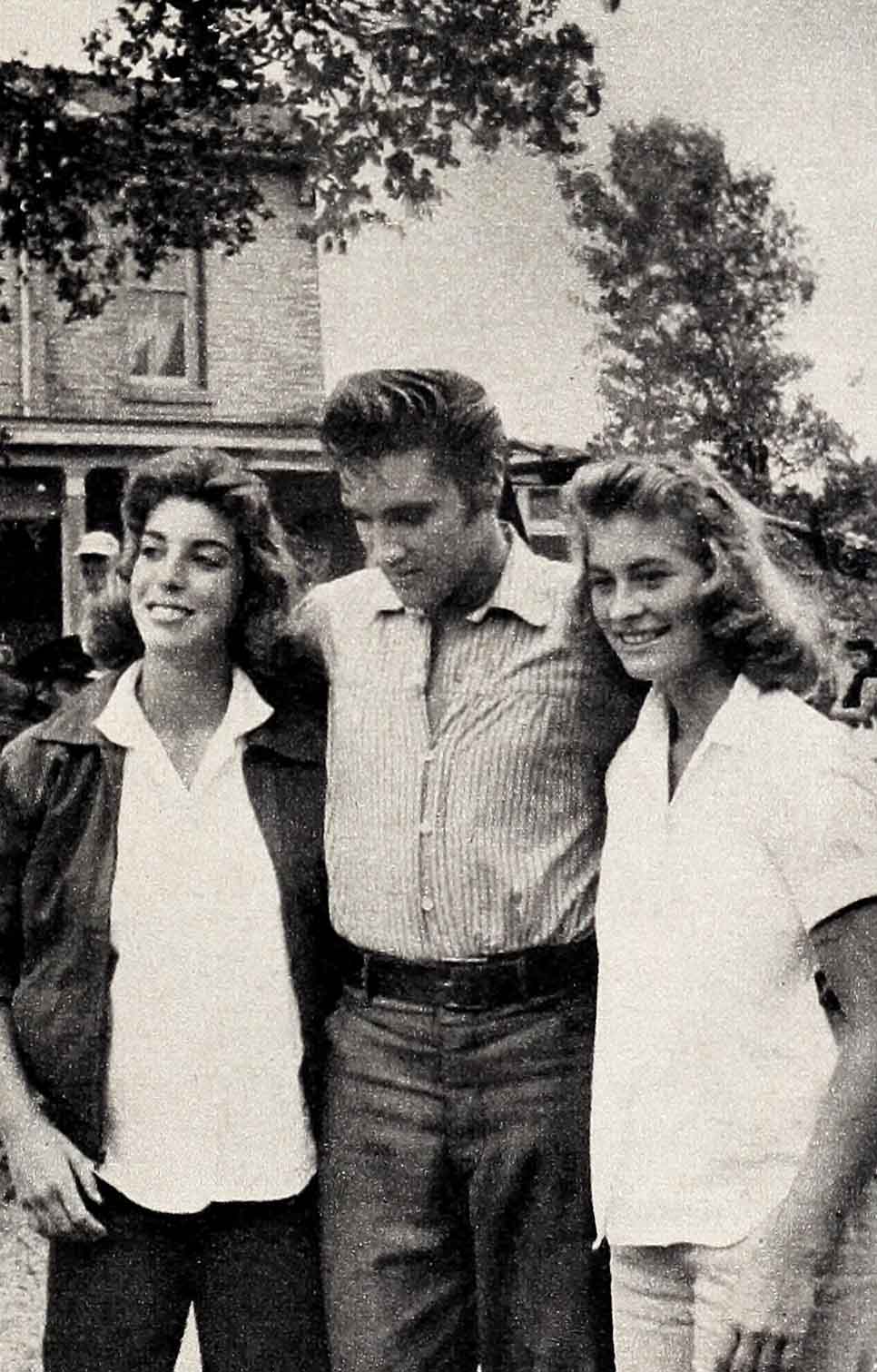

This conversation took place between Elvis and me in his dressing room at Fox during the making of “Love Me Tender.” I’d heard a great deal about him before I went out to The Ranch, where the shooting was going on, for my first meeting with him. I had a lot of preconceived ideas. As it turned out, I was all wrong.

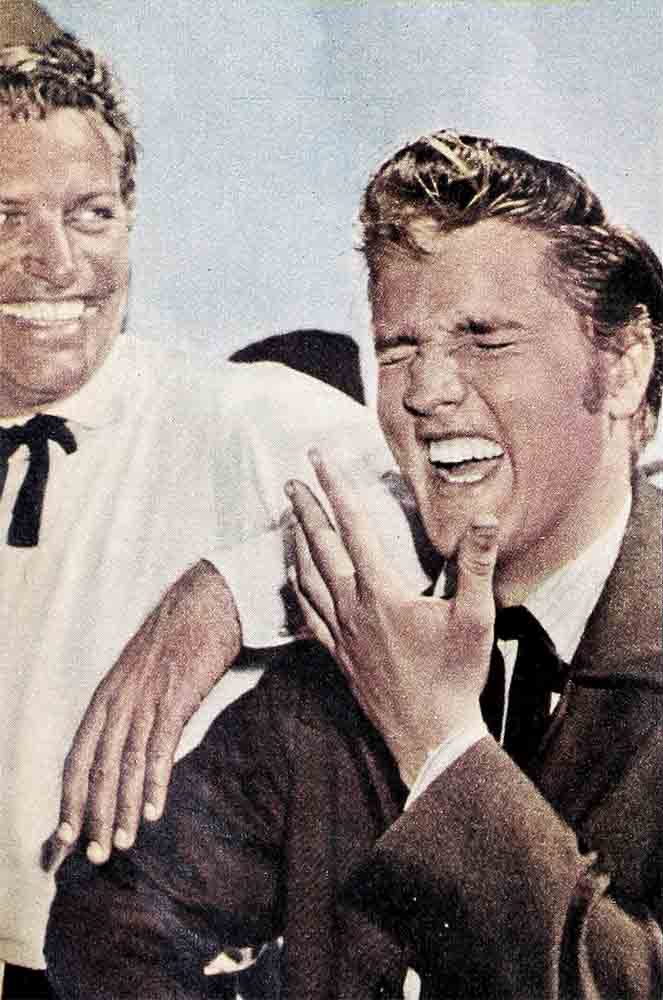

Nobody is laughing at Presley in Hollywood, although plenty are scared, in a way. Because he has a naturalness which Dick Egan, for one, regards as amazing.

“He must have been born with it,” Dick told me that day, “and it’s the kind of naturalness it takes fifteen years to get if you’re just an actor. I stand there amazed.”

Another Hollywood admirer of Presley is Debra Paget. “She’s crazy about him,” Dick Egan said. “But he’s still a kid. He’s boyish. He likes to sing harmony with the group. He likes to play. Look at him right now, for instance.”

I looked. Presley was practicing lassoing, coiling up a rope and tossing it at the steering wheel of a small truck about ten feet in front of him. He missed the target repeatedly but kept practicing.

“I got to learn how to be a cowboy with this thing,” he explained after we’d been introduced. “My trouble is, I can’t rope.”

He kept on tossing the rope with an underhand pitch while I took time to study him. I was surprised by his gentle manner and good looks. I guess I’d expected to meet a young hoodlum. Instead, a kind of careless glossiness clung to him—to his ducktail haircut, which shone even on this dank morning; to his reddish-white shirt, his tightish trousers and his neat-looking black cloth shoes. He looked citified—and yet the long sideburns didn’t seem out of place. I was impressed and surprised.

As soon as I could, I told him what Dick Egan had said.

Elvis hauled the lasso back, coiled it up again and made another pitch. “That’s real nice of him sayin’ that, but this is a complete new racket to me,” he said.

“These are some of the nicest folks I ever met. Including Debra Paget. In my opinion she is the most beautiful girl in the world.” Elvis’ eyes went searching for her around the ranch yard and finally found her, sitting on a porch.

“She’d sure make a pretty picture in a cotton field pickin’ cotton,” Elvis said, and with that he dropped his lasso, dashed like a wild rabbit over to the porch where Debbie was and plopped into her lap.

She squealed and shouted a little. But it seemed to be more in delight than in protest. The rocking chair squeaked and groaned under the extra cargo, so Elvis bounced out of Debbie’s lap. He loped back to his lasso and to me.

That was Elvis at play. Well, I had to admire his taste in playmates! And if that was Elvis being natural, I had to admire what comes natural to him.

Elvis has a lot of spirit and independence in his make-up. While he was generally meek and humble to the director and his fellow actors during the making of his first movie, he expressed himself clearly if he thought something was wrong. For instance, he objected to the title of the picture being changed to “Love Me Tender,” even though it would seem that this was a good way to plug his big song in the film. Besides, each time the song was heard, it would be plugging the picture. That was the “front office viewpoint”—the commercial way of looking at it. When this was pointed out to him by his manager, Colonel Parker, Elvis saw the wisdom of it. He relaxed and relented.

And, to sum up, I can see the wisdom of Hollywood in putting its money on this boy. May be Elvis won’t be another Valentino, or at least not the same kind of Great Lover as the passionate Rudolph—though I’m inclined to think he will. But he will go on for a long, long time.

THE END

Don’t dare miss: Elvis Presley in “Love Me Tender. ’

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK