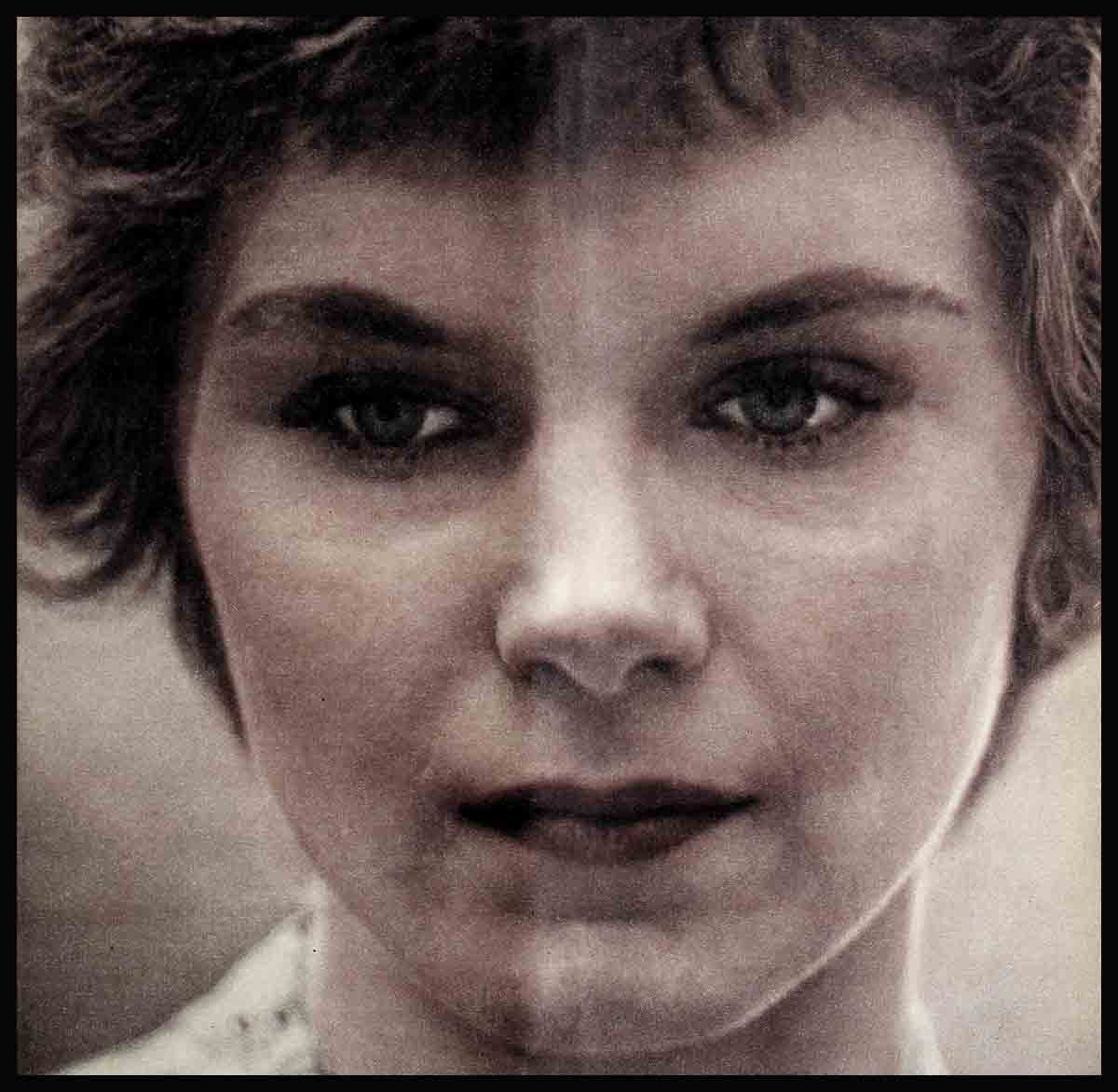

Diane Varsi’s Secret Tragedy

Diane Varsi walked out of the doctor’s office into the bright California day. “Result: positive.” How long had it been since that morning when she left her home in San Mateo, turning her back on the sick, unhappy life of her parents, on her own troubled childhood and young girlhood? She had walked south, determined to break the ties finally, somewhere to find herself. How long had it been since the night when the future seemed so full of promise, the way ahead waiting for her? Then she had put her hopes on paper: “Each of us has something to share. Small as it may seem to you—or to others—it is there for a reason. We may express it in many ways, some visible, some not. But somewhere, someone will appreciate it and think of it as beautiful.”

The fine thought couldn’t cancel out the simple, physical fact that confronted her. Diane felt hazy wonderment that the outside world was unchanged, the sun still shining, the hills still there above Hollywood, the same mahoganied men in sport shirts, blondes in toreador pants. For her own world was changed. She walked and walked, and at last she came home to the small apartment and told her roommate, “I’m going to have a baby.”

“We’d just moved in,” Diane recalls. “We didn’t have any furniture—just a couple of mattresses and a stove and a refrigerator and a black cat we’d named Mist.”

And she remembers her girlfriend’s illogical reaction: “You’re out of your mind, Diane! You can’t have a baby. Your marriage is annulled.”

Now Diane says slowly, “When I was first married, I wanted a baby so badly. But it didn’t happen then.” It happened while the two young people were finding they had almost nothing in common—no communication, no understanding, no mature love. And Diane discovered it after she and her equally youthful husband had separated forever. She had just turned eighteen. “I didn’t know what to do,” she says, “and I’ve never felt so alone in my life.” She had cut all family as well as marital ties; she had no job; she had very little money. She was going to have a baby. Also, Diane knew, she was quite ill, far beyond the natural upsets of her condition.

“I was very near a nervous breakdown,” she says, “plus malnutrition. I hadn’t eaten right for a long time. I seemed in a state of shock. I was vague about everything, could only speak in abstract terms. Sometimes I couldn’t speak at all. I’d have to draw a diagram on paper, make big letters very slowly. I was completely aware of a lot of things, but there are days I don’t even remember.

“I used to go out at night and walk and walk,” she goes on. “I knew I must be very ill. And I decided I was too sick to keep the baby after it came. That the only thing—the only fair thing to do—would be to give him out for adoption.”

How long had it seemed since that morning she had walked away from her home town—walking south—determined to break final ties and find herself somewhere?

How long? Days? Weeks? She sat back in her chair and let her mind wander back over the past weeks.

She had decided what she had to share could be said best through singing folk songs and she decided to travel south. As Diane says, “I never even thought of acting then. Ever since I was seven years old, I remember the only way I could relax was to sing, and I’d lock myself in the bathroom and sing. When I got older, I tried writing songs, and I’d found I could say a million things in a folk song.”

A girlfriend had decided to share the big adventure. “Mary wanted to teach school, and she figured she could benefit by seeing the world, too. We weren’t coming to Hollywood—we were just walking through. We thought we’d walk to Los Angeles and then walk on down toward Mexico.”

Diane had fifty dollars, and she gave her friend half of it. “I was taking a wicker bag,” Diane goes on, “packed with some folk songs I’d written, some apples and lemons and a couple of hard-boiled eggs. I’d done a lot of hiking when I was younger, and I remembered how when we got thirsty we would eat lemons.”

And so, one morning, without looking back at her hometown, a girl in blue jeans and T-shirt, her skin tanned from the sun, the bay breeze ruffling her short hair, started walking down the Bayshore highway, sleeping bag over her shoulders. There were deep scars inside Diane Varsi. It would take years to erase them, but that morning they seemed no longer there.

“I remember it was so beautiful,” Diane was saying now. “You know, everything so real and alive and beautiful.”

“I’m scared, Diane,” her girlfriend had said when they started out. “Will you be afraid?”

And Diane Varsi had said, “What is there to be afraid of? I’m not afraid of anything. People are people anywhere.”

Between San Mateo and Los Angeles, people were pretty much people, and there wasn’t too much to put into song.

Out of San Mateo three guys in a hot rod gave them a lift. “They thought we looked pretty strange, I guess,” Diane smiles. “They gave us a ride for kicks.” A salesman provided transportation later on, and thought he was slaying them with his monologue.

Soon, fortunately, two college kids who proved to be nice—“sort of the homey type”—offered them a lift into Los Angeles. “We got out of the car somewhere in Hollywood, I remember. It was very late at night.” And Diane Varsi remembers the strange feeling of foreboding she had. That something would happen here, something that didn’t fit in with her plans. Today she shakes her head, remembering how she’d felt sure Los Angeles could only hold bad luck for her, along with bad memories.

Diane’s friend called some people she knew, and they spent the night there. “It was somewhere over around Western Avenue. I remember we slept on the floor.” And two days later her friend surprised Diane with “I’m not going on with you. I’m going to stay here.” She remembers her feeling of panic and her resolve, when she felt better, to go on.

“I wasn’t feeling well at all. I was very run-down physically, and the food there didn’t help. The people were vegetarians and food faddists. I could have gone out and bought something—I still had my twenty-five dollars, but I figured I’d need this money. I planned on going on and never stopping,” Diane says. When she became sicker, they suggested she try fasting. “And I fasted, just taking distilled water. Then I remember another time, just eating bean sprouts. My eyes were swollen, I looked terrible, and I didn’t know what was the matter with me.”

One evening Diane went out for a walk, to get some fresh air. “I met some teenagers, and they were very nice kids. They invited me to have coffee with them, and one of the boys offered to drive me around the next day and show me Hollywood.

“He drove me out Sunset Boulevard, out by Schwab’s and Google’s and places like the Hamburger Hamlet,” Diane recalls. They had coffee, and Diane looked at the colorful, chattering groups around her. “This is kind of an interesting town,” she decided. “What happens here?”

The boy said, “Oh, actors come and talk.” What did they talk about? Diane wondered. “Oh, themselves and each other—they seem to be pretty lively people,” the boy observed.

“I think I’d like to sing around here. I think I’ll stay,” Diane decided. Possibly there was something she could learn here.

Grandfather Varsi had always wanted Diane to perform professionally. From childhood he’d told her, “You just dance, Diane—and I’ll take care of you.” So Diane found a small apartment just off Sunset, and her grandfather agreed to send her fifty-five dollars monthly. Then she ran into an old girlfriend who was studying at the Pasadena Playhouse and agreed to share the apartment.

Diane tried to work, and she worked at a bakery shop for one week, but she was feeling too ill. She went to the doctor for a check-up—it was then that she found she was also going to have a baby.

As Diane Varsi says quietly now, “I’d always felt from the age of seven, you don’t subject others to your problems.” She decided she’d just go on as best she could, for the time being. Meanwhile she would study—until she could know what to do, until she felt stronger and could plan.

“There was an audition for a musical show a fellow had written called, ‘Bottoms Up,’ and I went and started working with the group of kids there.”

During this brief period, Diane Varsi also met Jim Dickson, who was then associated with Vaya Records and who was to figure in her future so importantly.

An actor friend of Jim’s who’d met Diane thought he should manage her and help get her started in her career. He’d heard her sing a folk song one day, accompanying herself on a drum somebody had given her, and he was impressed. “Not as much with her ability to sing,” he’d told Dickson, “but with her ability to project.” He’d given her an improvisation to do, and he’d been amazed by her inventiveness. “This girl also dances like a dream,” he said, “but what’s more important, some day she can be a fine dramatic actress.” He thought perhaps Jim should start off her career making an album of folk songs.

Diane wasn’t too enthusiastic. “I don’t want to make records,” she said. “I want to see where I’m going. I just want to sing my folk songs. You know, be simple about it.”

And at first meeting, Jim Dickson was content to settle for her doing them this way. When he met Diane at the hall where she was rehearsing, his first thought was, “I’d better feed her instead of managing her.”

Not long after that, Diane Varsi told Jim she had another dream really in mind. “If I tell you something,” she said, “will you promise not to tell anybody? I want to be an actress. I’ve decided—”

“Well, don’t be afraid to admit it to anybody,” Dickson told her. “Just say you’re an actress. Start right now. Just say, ‘Now I want to be an actress. I’ll be an actress’—and start studying.”

But there was too much drama in the making in Diane’s own personal life now to concentrate on an acting career.

“I didn’t know what I should do,” Diane says quietly. “My girl friend had gone, and I was living alone now. I was really alone with it for the first time, and I was getting sicker and sicker. I knew I wasn’t well enough to keep the baby after it came. The only thing to do seemed to give it out for adoption. I’d heard there were places and authorities who would take care of such things, and who would also help with the hospital expense.” But Diane had called one of those places—and the voice was so casual, so matter-of-fact, so clinical. And the thought of putting the baby up for adoption frightened her.

“I thought I was out of my mind,” Diane Varsi was saying now. “And I was—some of the time. I would start screaming and yelling there in the apartment. And I’d go for walks and pick up little pieces of paper—”

Diane was nearing a collapse when Jim Dickson, who’d been out of town, returned and found her one day. “When I got back, I couldn’t find her anywhere,” Jim recalls. “The girls had moved while I was gone. Finally I located her.”

“We went for a ride, and we talked about it,” Diane goes on. “I told him about the baby—about my annulment—the whole story. That I felt I was in no condition to keep the baby—and there was nothing to do but give it for adoption.”

Jim Dickson asked her to marry him. He was in love with her, and somebody was going to have to look after her.

“But I didn’t want to marry Jim, then,” Diane explains. “I felt I couldn’t really evenly decide at that time. Because being pregnant, you’re quite liable to do something that’s not what you really want to do, or is right for you to do.”

Nor was this the time to make any decision about the baby, Jim Dickson pointed out. He arranged a room for her temporarily, where she would be in good hands. And he encouraged Diane to spend this time learning all she could about acting.

“I began to feel better, to get better, right away,” Diane says now. “Later on I found Otto Preminger was looking for an unknown to play St. Joan and I decided I’d try to get a reading for the part, hoping I would have the baby before time for my reading came. I knew I could do that part and I wanted to do it.”

There was the problem of photographs to be taken and submitted in order to get an audition. Jim Dickson’s recording business was inactive, and cash was scarce. “We had some great pictures taken of me in action in scenes ‘St. Joan’-—and Jim hocked something to pay for them. And then I didn’t have the baby in time,” Diane remembers well. “The reading was set a week before the baby arrived. I auditioned pregnant for ‘St. Joan’—and of course I didn’t have a chance at the part—”

But the producer had been very impressed with the pictures of Diane, they heard later, and he’d been very upset when she appeared at the audition in that condition.

Diane Varsi had made her decision about the baby now. She was feeling much stronger physically. “I decided that I was his mother, and that I would make a good mother. And that it wouldn’t matter if I brought him up alone. I told my grandparents and they came to be with me.”

And so Shawn was born—a beautiful baby, perfectly formed, the light of his young mother’s life.

Not long after this, Jim Dickson proposed again and made it very clear this would be the last time. “It was more of an ultimatum really,” Jim grins now. “We were having coffee together in a restaurant on Hollywood Boulevard. We were always having coffee somewhere.” And Jim had said, “If you want to marry me, we’ll do it—or else.” He was through talking about it.

And so they were married a year ago November in a little chapel just off Hollywood Boulevard. Diane was a lovely bride—in a wedding suit she’d made from a dress Jim’s sister had once worn as a bridesmaid.

“And from the time we were married until the time we were separated,” Diane was saying slowly, “we were always tired. Working and going and working and no sleep for either of us. I was taking care of Shawn and going to interviews in the daytime and to drama class at night. And I would get back home just in time for Jim to go to work. As for Jim—”

Jim Dickson had taken a night job in RCA-Victor’s pressing plant, working from midnight until seven in the morning, to be able to drive Diane to studio interviews in the daytime and to babysit with Shawn while Diane was in class at night.

In the strange ways of Fate, Diane’s drama coach, Jeff Corey, had run into Director Mark Robson one day in a delicatessen in Westwood. Robson had always told him if he ever had anybody in he thought was really an exciting talent to let him know. The director said he was looking for a girl to play Allison in “Peyton Place,” and Corey told him about Diane, who was acting in her first play, “Gigi,” in a little theater. As Jeff Corey said, “I’d never recommended anyone before, but when you find a talent that is so exciting, you want people to know about it to let them share it.”

Diane was excited, too and very grateful, although she had never intended starting her career in such a large way. “I felt they made a wrong choice at first. I felt I wasn’t ready to do it, and I wasn’t, really. I think I could have done it much richer now.”

Diane’s and Jim’s marriage had very little time to mature during this important adjustment period. And when Diane Varsi plummeted into stardom in motion pictures at 20th Century-Fox in her first part, there was no time at all.

Following her fine poetic performance in “Peyton Place,” Diane starred with Don Murray in “From Hell to Texas” following that immediately with the important dramatic emotional role of Gary Cooper’s daughter in “Ten North Frederick.”

As business pressures and demands on her increased, Diane turned them over to Jim with, “You’re my manager; will you talk to them?” And when their conflicts added to other pressures seemed too much and they separated, Diane still wanted Jim to be her personal manager. He was still the person she trusted most, the only one perhaps in the life she’d known to ever give her a fair shake. And “Because he’s a smart businessman—and because, well Jim knows me—and he doesn’t bug me.”

There seemed even then a bond between these two that’s too strong to break—one that’s already weathered too much.

And as this is written Diane Varsi and Jim Dickson are back together again. “Nobody knows yet,” Diane was saying now. “We’ve told the attorney to hold off any action for the time being.” They wanted to avoid the static and the comments and spotlight as long as possible. To really give their marriage every chance. And every day was all-important now—a brand new thing.

The story of Diane Varsi is far from written. She may be the most famous star in Hollywood—or she may quit motion pictures tomorrow—if she believes she will be useful to others in another field.

“I’m not sure which form may be the answer,” says Diane. “Whether it will be acting or what. I just want to use myself as a human being and see what comes of that.” She’s gradually growing more secure, and it’s a significant step in this direction—working so hard at her marriage and thinking toward buying a home in Hollywood.

Through the sheer strength of her own character and talent, Diane has come through adversity to stardom. She’s received honors and recognition in Hollywood for her performance in her first picture. Twentieth Century-Fox has big plans for her future. Today she has a “family” of millions of fans who feel close to her and who assure her a home there.

But there are times when she still feels deeply insecure. As Diane puts it, “Is acting just an escape?”

Is she still running away? Like the little girl with the troubled blue eyes who used to run away up into her own live oak tree back in San Mateo—away from the house with the ghosts and wonder who she was and why parents seemed so strange to her?

For Diane Varsi there is still the familiar feeling sometimes that today is just the sun before the shadows. The sun, as ever, just out of reach. And that perhaps she’s living in a world of pink cotton candy that can collapse around her and leave her standing there with nothing.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1958

No Comments