“Acting Is Our Profession . . . But Freedom Is Our Cause”

By eight o’clock that morning the sun was already high and everyone knew that in addition to all the other problems, it was going to be a hot, sticky day. And this could be dangerous, because in the heat everything that had been planned so carefully could easily fall apart. People would be uncomfortable, people could get sick, tempers might flare, violence might be triggered. And then all the hope that had been built on this day would dissolve into hopelessness. And in the midst of all this stood a group of Hollywood stars anxious and expectant, glad to be involved, but perhaps apprehensive. Because they all knew that for whatever they might gain today, they could lose something else, something that was important to them, too. And so the day began—a day of fear, a day of hope. A day of drastic change.

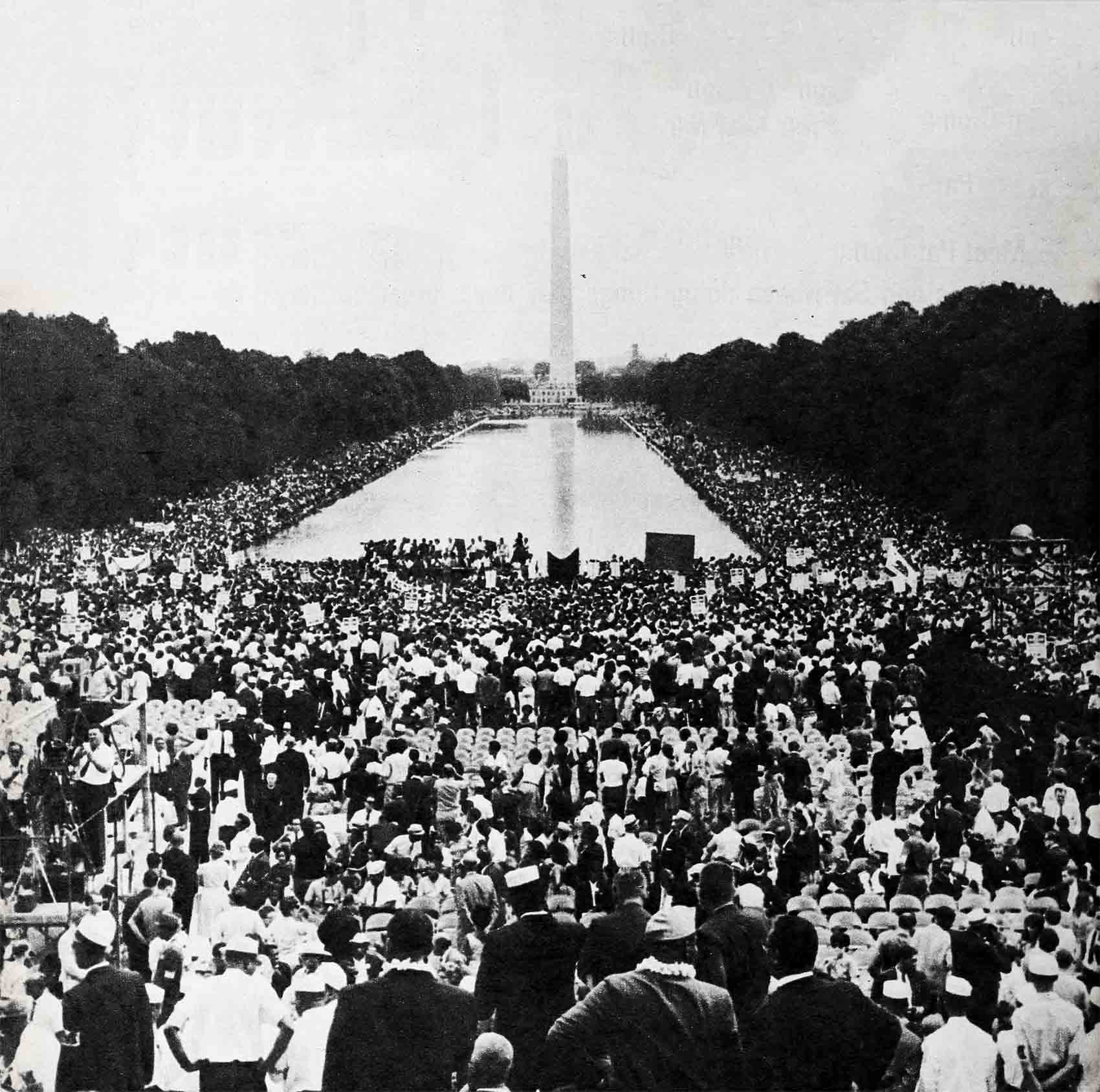

All across the country people began turning on tele. vision sets—and perhaps you who are reading this now were one of them—for even if you were only curious, even if you didn’t know it at the time, it was a day that will change your life. For this was the day of the March on Washington, D.C. for Jobs and Freedom. From all over the country more than 200,000 people poured into the capital of our nation.

Their plan was to show Congress, by sheer strength of numbers, that they wanted equality in jobs and human rights for all people. They were made up of Negroes and whites and famous people and unknown people. And they included a group from Hollywood. Many stars had wanted to take part in the march. They believed in the cause and they want to show it.

They said they were demonstrating as private citizens, but they hoped they’d influence their fans. They said they didn’t care if the publicity would hurt or help their careers, and they knew some damage had already been done at the box-office. But they were committed now—and for this day and all days to come—they would have to place their commitment before their careers. Photoplay knew this—and that is why they sent this reporter to watch them, to find out what they felt and why they felt they had to involve themselves in this heroic movement. Among the marchers were Paul Newman, Burt Lancaster, Sammy Davis, Jr., Marlon Brando, Robert Ryan, Harry Belafonte, Charlton Heston, James Garner, Tony Franciosa, Steve Cochrane, Virgil Frye, Rita Moreno, Sidney Poitier, Susan Strasberg, Lena Horne, Frank Silvera, Diahann Carroll and director Joseph Mankiewicz.

This reporter must now count herself as part of this story. Because I suddenly found myself in an unexpected position for finding out why Hollywood stars, at some cost to their careers, took part in this day.

And here is how it happened. . . .

The long day starts

For the stars, the day really began at a 9 A.M. press conference at Washington Airport. But for me, the day began much earlier. I had to be at Police Headquarters at 6 A.M. to pick up my press pass. This was very important, because I would not be allowed near the stars without a pass pinned to my blouse. All the other reporters had them—big, easy to see and properly accredited.

The officer at the stationhouse was very polite when he said he couldn’t explain why, but through some snafu there was no pass for me. He mumbled something like, “Sorry you had to come to Washington for nothing.” I was sorry, too. It was perfectly clear that I would get no story that day.

How wrong can you be?

I thought, I’ll try to get into the press conference, anyhow. I knew what was going to happen there: the stars were to make one joint statement, and that would be all. No individual interviews.

But I was wrong again.

There was a guard on duty at the airport conference room, but I walked right past him. I opened the door—and bumped into Paul Newman. It turned out that the stars were coming in on different planes—some from New York, some from Hollywood, Burt Lancaster came from Paris—and some of the planes were late.

So now there was time for individual interviews.

I asked Newman why he was involved in this. “I don’t have control over my destiny,” he said, “but that doesn’t mean I’m not going to stick my finger in where I think it’s needed. I want— need—to be committed to something I believe in, that’s why. And this commitment represents democracy in its best, its deepest sense. We are all here today because we are all terribly hopeful—200,000 people with a desire to be felt, a desire to influence Congress to pass civil rights legislation.

“But this is not an angry pressure group. These people are joyous and optimistic. I’m happy to be part of it.”

As to the publicity, “I don’t think it will help,” he said. “My box-office will probably be hurt. When Marlon Brando and I were in Alabama, his movie, ‘Mutiny on the Bounty,’ was scheduled in a movie theater, but it was yanked. And I have gotten some bad mail. I think it might hurt me with the older people, but maybe not with the young ones. Some people say I’m using this to get publicity, but there’s nothing I can do about that. Except point to my record—I’ve been involved in this for a long time, you know.

“In my industry there’s never been discrimination on the part of creative people. I’m not coming here as an actor, I’m just an outraged citizen. It is the problem of every citizen to choose whether or not to make himself felt. Of course, acting is my profession, but freedom is my cause.

“I can go down South any day for a charity—and that’s fine. But not if I’m interested in the Negro and white community. Then they call me an outsider.

“When I was in Alabama, with Brando, I admit a lot of people came out to see us because we were stars. But we helped. I hope this leads other stars to take a greater part in political movements.”

Just then a young Negro dressed in overalls came over to Paul. “A person of your caliber is not exposed to the real sorrows of our people,” he said. “I wish you could see the real violence in Alabama—then you could let the people know. Mr. Newman, you’re not really important. You’re only important because you’re human. And I’m human. And that’s my importance.”

Newman looked at the boy for a minute and said nothing. Then he put his hand on the boy’s shoulder and murmured, “I’ll do what I can.”

I walked over to Sidney Poitier. He smiled, “Well,” he said, “I think we’re present at the unfolding of a new era. This March today is certainly an expression of what the Negro community and, to a large extent, the white world feels has gone on for too long. No Negro enjoys complete freedom. Often I can’t live where I want to. Often, I can’t work—I can’t exercise my skills. It’s true that little gains have been made. But you can’t consider them as ends in themselves. We can’t honestly evaluate progress until complete equality is available to all Americans. And I don’t mean just Negroes and whites—I mean Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Chinese—all the minorities.”

Director Joseph Mankiewicz came over. “There is something we can do to help,” he said. “We can keep our pictures from playing at segregated theaters. Brando, for instance, is a producer. As such, he can refuse to allow any of his pictures to be shown any place that discriminates against minorities. A Brando movie brings in money. If the theater owners are hit in the pocketbook, they’ll cut the color line.”

“To defend this country . . .”

Burt Lancaster nodded his head. “I’m in Europe a lot and I find that I constantly have to defend this country. The European people are very concerned about this matter. We can’t afford to let our country look bad in the eyes of the world.”

I asked if he thought that he could influence his fans.

“I hope to influence people,” Lancaster said. “If it hurts me—if I lose fans—I’ll worry about that later. But in terms of my conscience, this is something I must do.”

“Look,” Robert Ryan said, “I feel this way: The only thing that can affect my career is what pictures I make. If I’m still around, after all the bum movies I’ve been in, then nothing can hurt. But I think what goes for me is true for all of us here. It’s too late to worry about things like a career and publicity. My children and my country come first.”

“That’s right,” Sammy Davis said. “You do feel this so much more because of your kids. Years from now, when my kids say to me, ‘What did you do?’ I want to have something to tell them. This isn’t my problem because I’m Negro—it’s everyone’s.”

At that moment there was a flurry of excitement as Charlton Heston, Marlon Brando, James Garner, Tony Franciosa and the rest of the Hollywood contingent came in. “We’re just going to read our statement,” Heston told the reporters. “Then we have to leave for the March.”

“We punish ourselves”

“As artists and human beings,” he read, “we rejoice in the knowledge that human experience has no color and that excellence in any endeavor is the fruit of individual labor and love. And we believe that artists have a valuable function in any society, since it is the artists who reveal the society to itself. But we also know that any society which ceases to respect the human aspirations of all its citizens courts political chaos and artistic sterility. We need the energies of these people to whom we have for so long denied full humanity; we need their vigor, their joy, the authority which their pain has brought them.

“In cutting ourselves off from them, we are punishing and diminishing ourselves. As long as we do so, our society is in great danger, our growth as artists is severely menaced and no American can boast of freedom, for he cannot be considered an example of it.

“We are here, then, in an attempt to strike the chains which bind the ex-master no less than the ex-slave, and to invest with reality that deep and universal longing which has sometimes been called the American dream.”

The statement had been written by James Baldwin, but Heston added some words of his own: “The actors and the drama are in Washington this week. And the name of the play is democracy.”

And with that, the press conference was over.

All the reporters were then asked to leave so that the stars could get on their bus for the Washington Monument. But reporters are notoriously slow to leave a press conference, so they were individually shown out of the door.

Nobody asked me to leave.

I suddenly realized that without a press pass pinned to my shoulder, nobody knew I was a reporter. They apparently assumed that I was one of their group.

Someone said, “The bus is here. Everybody get on, please. Hurry up, we’re late. Hurry, Miss.” I held my breath and got on the bus. It looked like I was going to see the March like no other reporter was going to see it.

“Hey, Sammy,” someone laughed, “move to the back of the bus!”

Sammy Davis laughed, too, and went to the back.

“That’s right,” somone said with a mock Southern accent, “You-all stay back there where you be-long.”

It got a big laugh and we started out. We didn’t go directly to the Washington Monument as planned. It was late, so to save time we got off the bus fairly near to the scene of the ceremonies, the Lincoln Memorial. We lined up three abreast, MP’s lined up on either side of us. And we marched to the Memorial.

It was a good thing the MP’s were there, too. When the crowds saw the stars they tried to break into our lines. It was a very frightening time. The people were glad to see the stars, glad to see people like Newman and Brando and Heston taking part in what they felt were their troubles. They tried to thank them, but in the mob we were pushed and shoved and the MP’s tightened around us protectively.

Friendly but frightening

“How you doing, Marlon, baby?” they yelled.

“Hey, there’s Robert Ryan!”

I was marching next to Robert Ryan. He looked very calm and confident, smiling at the crowd. Then I heard him whisper, “This is terrifying. I’m scared to death.”

Finally, we got to the Memorial.

“We Shall Overcome,” the theme song of the March, opened the ceremonies. Then Odetta sang, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hand.” It was very hot. Susan Strasberg reached into her huge pocketbook, took out a wide brimmed hat and a portable electric fan and settled down.

Up on the podium, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth said, “Freedom belongs to anybody. It belongs to everybody. And until everybody has freedom, nobody is free.” Sammy Davis nodded his head vigorously and took out his camera to take a picture of the Reverend.

“We’re going to walk together,” the Reverend cried. “We’re going to moan together. We’re going to groan together. And everybody is going to be free. Free. Free. Free!” Tony Franciosa yelled, “That’s right. Reverend. Tell it like it is.” Rita Moreno put her hands on my shoulders, “Oh, God,” she said. “Wasn’t that lovely?”

The speeches went on, and the singing, and the day got hotter and longer. Somebody came around and handed out bottles of soda. Susan Strasberg reached into her big bag again and brought out lunch, which she shared with everybody near her. She was the only one in the group prepared for the discomforts of the day.

Dick Gregory went up to the podium. “I had to get out of jail to come here today,” he told the crowd. “I never thought I’d see the day I’d give out more fingerprints than autographs.”

The stars laughed more than anybody else, they clapped more, they were more moved. And they took more pictures. One by one they took out their cameras and snapped the crowd snapping them.

Burt Lancaster and Harry Belafonte were on the podium, now. Lancaster said that 1500 Americans in Paris marched to the American Embassy in support of this March today. “This is one of the most amazing demonstrations for human dignity that I have ever seen,” he said.

Belafonte’s wife, Julie, sitting next to me, said, “Look at Harry. He’s so hot. He’s literally going to bust a gut. I worry so about his health.” She added, “You know, coming here, my plane was struck by lightning. What a scare! But we got here.”

A. Phillip Randolph, the union leader and a leader of the March, was the next speaker. “This is a new beginning—not only for the Negro, but for all America,” he said. Rita Moreno called out, “Don’t worry, it’s all coming!”

Just then a group of Senators and Congressmen arrived. The crowd applauded and cheered and then started to chant, “Pass that bill. Pass that bill. We want freedom now!” One of the Senators saw Sammy and yelled, “Hey, I saw you work at a night club last week. You were great.” “Thank you,” Sammy called back. “I hope I’ll be able to say the same of you when the Civil Rights bill comes to Congress.”

Reverend Martin Luther King made one of the closing speeches. “When we allow freedom to ring—when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state,” he said, “we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children—black men, white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics—will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-mighty, We are free at last.’ ”

Now, for the group of stars, the March was over. They had to leave a little early to avoid the crowd. Like all the other Marchers, they were hot, tired and hungry. But they were happy. The day had gone off beautifully, and they had helped.

A glorious day

Now they were going to a party at the home of New York’s Senator Jacob Javits and they asked me to join them. By then I had confessed I was a reporter.

Sybil Burton was at the party. “Wasn’t it a glorious day?” she said. “I wanted to march, but I was afraid people would think it presumptuous of me, since I’m not an American.”

“I had the best time at the March,” Lydia Heston said. “I stayed with the real Marchers and not with the Hollywood group. We were told that there might be some trouble, but you see there wasn’t any. It was a perfect day.” She meant the violence that everybody feared and nobody would talk about. But she was absolutely right—there had been no trouble.

And now the day was over. It was time for me to go back to New York. “But it’s not over,” Harry Belafonte told me. “This is only the beginning.”

And that’s how this day will affect you. Because now the changes are beginning. If you go to a segregated theater, you won’t see the stars who are committed to civil rights. When you turn on your television set, you’ll see Paul Newman or Tony Curtis asking you to join their cause. And there’ll be more—much more.

Because these stars believe fully in this movement. They want to be part of it whether it helps them or hurts them, makes you like them or dislike them.

For as Lena Horne said, “This is a new revolution. And—white or black—you’ve got to either be involved in it, or be left behind.”

And these stars just don’t want to be left behind.

THE END

—BY MICKI SIEGEL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments