Happy Anniversary—John F. Kennedy & Jacqueline Kennedy

At exactly 4:30 P.M. on Wednesday, September 12th, the President of the United States and his Jacqueline began the tenth year of their marriage. The tenth year—according to Tiffany’s—is the year of tin and aluminum and/or diamond jewelry. Well, it just so happens we didn’t have any pots or pans or diamond bracelets or stick-pins on hand to offer the First Couple of the Land. But we would like to offer instead to them—and to you—this yearly account of their first credibly beautiful and heartwarming nine years together.

September 1953-1954 The first year was gay. It started gayly, at least. They honeymooned in Acapulco, in a tiny dream cottage, pink—pure pink, nestled in the hills, overlooking the blue-green Pacific. They swam. They played tennis. They went for dinner in small out-of-the-way restaurants, with waiters who recognized them saying, “Mucho gusto, Senador y senora.” And serving them chicken-stuffed enchiladas and crisp tacos and paella and red wine, all by soft candlelight. Then they went dancing in one crowded nightclub or other. And then back to the cottage. And to the long nights together. And finally to breakfast together, just the two of them, on the terrace of their little pink place in the hills. They drove, leisurely, through Southern California after that. Then, they returned to Washington.

Jack went off to the Senate. This was a hard and tense year, the year of the much-publicized Congressional investigations of McCarthy. Jackie tended the small house they had temporarily rented. Like a little girl—like most new brides—she played house at first, really. She learned to cook a little—“potato and noodle casseroles, Jack loves these.” She saw to it that his socks matched when he left the house in the morning (they hadn’t always, before this).

She stood by the phone around lunchtime waiting to hear how many constituents from Massachusetts her husband had invited home for lunch today. Eight? Fourteen? Forty? She learned to cope, in time, with any given number.

Afternoons she drove over to the Georgetown School of Foreign Service where she took courses in American history. Before this she had always said, “European history—so full of intrigue—is for women; American history—so stark—for men.” But Jack was her man now and Jefferson and 1812 and Lincoln and Wilson and FDR were his loves and, good bride that she was, she was bound and determined to please her man by learning to share these loves.

Evenings they went out quite a bit. Just the two of them, mostly. Just to movies or concerts together. To very few parties. Or else they stayed home. And read—in the living room, in bed, it didn’t matter where.

Once in a while Jackie, whose memory is reportedly fantastic, would surprise Jack by reciting to him long passages of his favorite poem, John Brown’s Body, which she had learned by heart.

Many nights they would go to bed extra-early—would have to, because there was a trip somewhere the following day—to London to confer with Churchill, or to Paris for lunch with Bidault, or to Omaha to attend a convention of the United Carpenter Workers of America.

There was always somewhere to go, someone to see.

It was a hectic first year.

But it was gay, too, and young and wonderful.

Until one day in the summer of that first year when Jack suddenly looked very old and tired. He had lost an alarming amount of weight suddenly, Jackie could see. He was beginning to have great trouble walking or sitting or standing or doing anything comfortably. The cause, she knew, was his back—that injury he’d sustained in the Pacific, in World War II.

On the eve of their first anniversary, some friends gave them a party. Jackie had been looking forward to it for weeks. And Jack was not one to disappoint his wife. But in order to make the party that night, he had to use crutches.

“We won’t go,” Jackie said.

“Why not?” Jack asked, covering his pain with that boyish grin of his. “People will probably think it’s a gag. It’ll be good for at least one laugh.”

But there was no laughter when, midway through the party, Jack dropped one crutch, then the other—when Jackie, from the other side of the room, rushed over to keep him from toppling to the floor.

September 1954-1955

It was exactly thirty-eight days after their first anniversary when Jackie accompanied her husband to the New York Hospital for Special Surgery.

An operation was performed on him immediately—a spinal fusion, it was called. And it was, unknown to Jackie, a failure. Unknown, that is, until the night, forty-eight hours after the surgery, when she got a phone call from the hospital.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Kennedy, but an infection has set in. Your husband is very, very ill. I’d suggest you phone any members of the family who are in New York. And a priest. And come over immediately.”

Jackie looked down at her husband, a little while later, as the priest intoned the last rites.

She barely heard the words: “Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna . . .”

She could only see that her husband’s face was pale and swollen . . . that his breathing was heavy, irregular . . . that his eyes puffed out of their sockets.

She placed her hand on his forehead. The fever singed her fingers.

“Help him. Mother of God . . . Oh help him,” she whispered. And in time—following what was called a “tentative recovery,” then another operation, then a long period of recuperation—he was helped.

And back on his feet again.

And back in Washington.

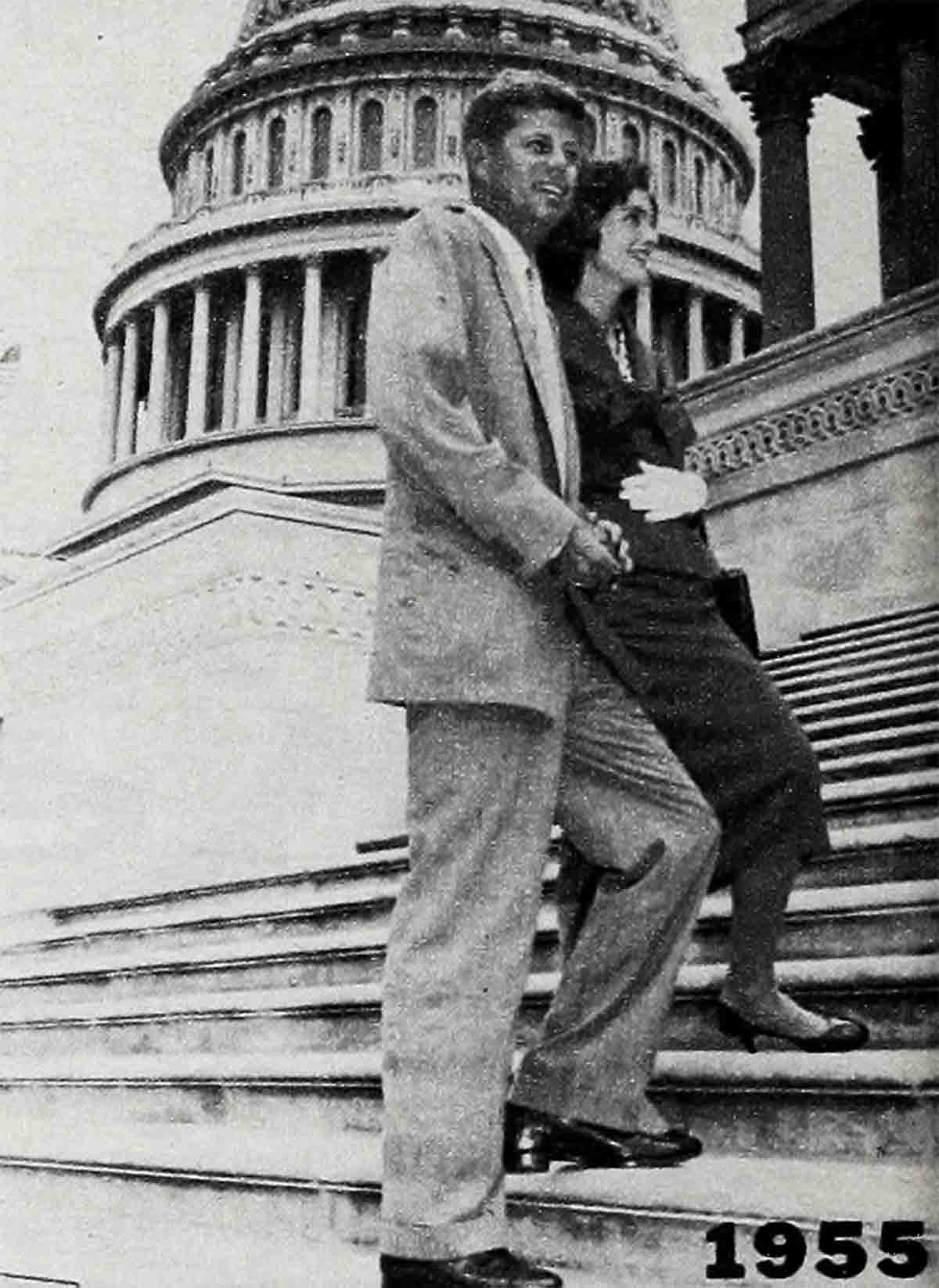

Writer James Burns has said of that day: “Something like a hero’s welcome greeted Kennedy when he returned to Washington on May 23, 1955, after seven months’ leave. Family and friends crowded around him at National Airport, where he had flown in from Palm Beach with his wife and his sister Jean. Jubilantly, (administrative assistants) Reardon and Sorenson drove the couple to the Capitol, briefing Kennedy on the way about the latest political and legislative gossip. When the Senator posed for newsreel and television cameramen on the Capitol steps, tourists grabbed his hand, and a delegation of textile workers from the South that was passing by stopped to cheer him roundly . . . In his office were many flowers, one bouquet ‘Dick Nixon’. . . .”

Another writer, a Washington society reporter, noted that “Jacqueline, his wife, looked pleased as punch. She simply glowed with happiness!”

Very few people, including the society a reporter, realized at the time that it was all Jackie could do to make it to Washington that day. That less than ten days earlier she had suffered a miscarriage.

It hadn’t been critical. She’d only been pregnant seven or eight weeks. There’d been little pain or danger—as there would be the next time. But still, she had lost the child she’d longed for.

And it hadn’t been easy for her to make this trip this day, to stand at her husband’s side “glowing with happiness.”

September 1955-1956

The beginning of their third year of marriage was marked by the purchase of a $125,000 house near the town of McLean, Virginia, just outside Washington. It was an estate, really. It had everything. A swimming pool. A stable for horses. An orchard and gardens. The house itself was twenty rooms large with—most important—a wonderful old nursery right next to the master bedroom.

Even before she had conceived for the second time, Jackie would spend hours in the room planning where the crib would go, the bathinet, the playpen, the shelves for toys and books. She’d tell Jack about her plans when he got home at night. And he’d smile and hold her hand a bit and say. “Yes, yes, that’s just the way it will be.”

But the truth seems to be that Jack’s mind wasn’t on his home very much those days—nor on his wife—nor especially on a baby not yet within a whisper of life.

He was, at the time, beginning to emerge as a national politician. His book, “Profiles in Courage,” written in the hospital the year before, was now a best seller and Pulitzer Prize winner. He was engaged in debate after Congressional debate—all of them tough and important. Invariably, he emerged the winner.

Shortly after the second conception did take place. Jack made up his mind that he would try for the Vice-Presidential nomination at the Democratic convention in Chicago in June.

He was rarely home after that—instead he was off campaigning for political support, criss-crossing the United States.

His wife was a very lonely young woman after that. For the next six months she i barely saw her husband. Even in late June, after his failure to get the nomination (Kefauver had won it instead, and would run with Stevenson in the fall), Jack somehow managed to stay away from his wife for a while.

Disappointed at his defeat, tired, he went with his brother Bobby to his father’s villa on the French Riviera to rest for a few weeks.

Jackie, meanwhile, in her seventh month now, drove up to her mother’s summer place in Newport, Rhode Island.

One gray morning, alone, she went walking along the beach. Suddenly she stumbled and fell. Normally she would have gotten up, brushed off the sand and continued walking.

But she couldn’t get up this time—there was something wrong, she knew; something wrong with her baby, something terribly wrong.

She dug her nails deep into the sand. She screamed for help. A teenaged boy, on his way for some fishing, heard her and ran towards her.

A little while later, Jackie lay in the hospital. An emergency Caesarean was performed. Her baby was removed from its mother’s womb—dead.

The following night, after a flight from Nice to Paris, then Paris to New York, then a dash by car to Newport, Jack arrived at his desperately sick wife’s bedside.

He stood there for a long moment, looking at her. She lay looking up at him.

The tears—it is said—came to their eyes at exactly the same moment. And, then, still without words, Jack bent and embraced his wife.

And they wept softly together.

And as their tears touched and melted into one another that night something, at least, was born to them: A strength and understanding that would never, could never, be taken away from them.

September 1956-1957

The fourth year was one of hope for the Kennedys, one of beginning things afresh.

Politically, Jack began to realize that his defeat at Chicago had not been that at all; that errors of judgment had been made by himself and by advisers; but that actually—thanks to his own good looks and charm, to TV, to the exceptionally good speech he had made introducing Stevenson—the public remembered him. His political stock had actually been enhanced.

So, politically, Jack canned his disappointment and got back to business as usual. Domestically, he and Jackie sold their Virginia place to brother Bobby and his Ethel—who with six children and a seventh on the way could better use the twenty rooms. And Jack and Jackie moved into a rented house on N Street—where they vowed to stay until their own family grew a little larger.

Almost superstitiously, now, they never talked about nurseries nor babies nor what they would call the little thing if it were a boy, or what if a girl. They’d had their fill of that kind of heartbreak.

Jackie, as it were, packed away her maternity clothes. Jack put away the cigars. They began to travel again—together again.

“It was,” as someone has said, “the period of their greatest closeness—they were barely ever apart. They went to California, the Carolinas, Utah, Maine, Arizona, Texas, New York, New Jersey. Jacqueline would have gone to the moon with him, if he’d asked. It was as if she sensed somehow that one day soon it would not be this way anymore—at least not for a long, long time.”

And so they practically clung to one another now, the dashing Senator and his beautiful wife.

And when, one day in early May of 1957, she learned that she was pregnant for the third time—she barely whispered the news to her husband, lest something terrible should happen to the bud inside her.

They spent the summer together very quietly, again at Jackie’s mother’s place in Newport. Only this time there was a hand holding hers every time she walked down the long stretch of beach.

They returned to Washington in early September and bought a house in Georgetown—not too big. not too small—which would become to them, in Jackie’s words, “the sweetest house in the world, with its slanted roof and its staircase that creaks a little.” It was a house, incidentally, into which they had no plans of moving until the following December.

Instead—quietly, hopefully—they remained for those last few months of Jackie’s pregnancy in the rented place on N Street.

And they waited.

September 1957-1958

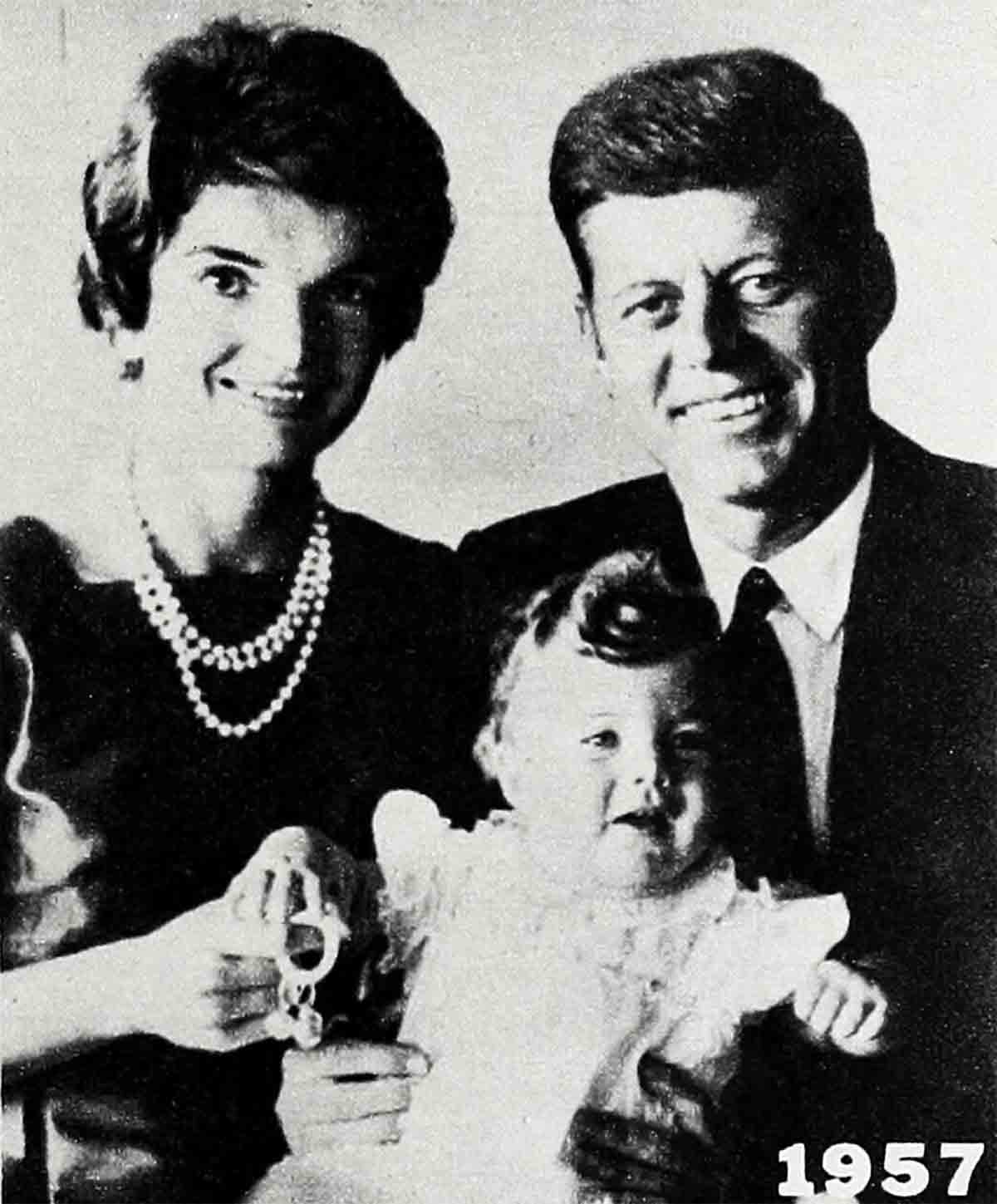

The fifth year—all of it, its happiness and its joy—is contained in this simple little announcement which appeared in a Washington newspaper one morning in November, 1957.

“Mrs. John F. Kennedy, wife of the Senator from Massachusetts, gave birth last night to a daughter. The child will be named Caroline.”

The date of the announcement was November 28. It couldn’t have been more appropriate —coming, as it did, in the middle of the Thanksgiving season.

September 1958-1960

To say that Jack Kennedy’s political star began to shine during these sixth and seventh years of his marriage to Jackie, would be like saying you can find a bulb or two on Times Square if you look hard enough.

Actually, his star began to blaze. In November of 1958 he ran for Senate reelection in Massachusetts and defeated his rival, Vincent J. Celeste, by a margin of 874,000 votes—the largest percentage of the vote received in 1958 in any major senatorial contest in the country.

In 1959 he took his chances and guided quite a few controversial bills through a Senate which, as one observer has put it, “was dominated by conservatives and Presidential rivals.”

By early 1960 it all seemed clear: Jack was the man the Democrats would put up to run for President that coming fall.

And Jacqueline, by now a political trouper herself, couldn’t have been happier. Although, deep down, most of her happiness was reserved for her husband as a husband and, of course, as a father now; for herself as his wife and, of course, as the mother of his child.

The little word pictures given by friends relating to that time of their lives are all that is needed to show exactly the fulfillment that Jackie felt.

Mary Van Rensselaer Thayer, an old friend of Jackie’s, has written in her book “Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy”: “After Caroline came . . . her safe arrival seemed so incredible that Jacqueline would try to stay awake at night to banish sleep as long as she could so that she might savor in extra minutes how happy she was and how overwhelmingly she loved her baby girl and Jack.”

A friend of Jack’s has said: “There’d been a time when Jack thrived working on weekends. Everybody else relaxed then, he figured—so it was time for him to get those extra innings in. But something changed in him after Caroline was born. I remember one Saturday morning he was just about to take off for his Senate office. Jackie was standing at the door with him, holding Caroline, who was about two years old and just beginning to really talk. ‘Daddy—’ the little girl said. ‘Yes?’ Jack asked. ‘Daddy—you have to go ’way—again?’ the little girl said. Jackie winked at him on that one. Jack winked back. He put down his briefcase. He took his daughter from her mother’s arms. And that was just about the end of Saturdays at the office for a while—political star or no!”

September 1960-1961

Political indications of the previous two years turned out to be correct. And Jack Kennedy was indeed running for the Presidency of the United States as he and his wife began their eight year of marriage.

In a few months’ time, in fact, Jack would win the election. His wife would be First Lady.

But to go back just a little, to September 12. 1960 (some fifty-five days before the election)—this was the first anniversary which Jack and Jackie had ever spent apart from one another.

Jack was in Salt Lake City that day, beginning the windup of his campaign against the man who had once sent him those flowers, Dick Nixon. Jackie was 2500 miles away, at their summer home in Hyannis Port.

With her was Caroline, now nearly three. With her, too—within her—was her soon-to-be born son, who would be named John, after his father. With her, that night, were her prayers for her husband’s victory, for the ultimate success for which—to her—he had seemed so destined.

She sat at a desk that lonely September night of their anniversary. And—Caroline asleep now and a servant in a nearby room watching TV—Jackie wrote a letter.

Actually it was one of the Campaign Wife newsletters she had been writing all along, printed in newspapers across the country as part of an appeal to women voters to vote for her husband. But in a way this particular letter was to Jack, too—a sort of open message to the man to whom she was married, whom she loved and whom she missed very much this night.

It began: “I have been back in Hyannis Port for almost a week now. This little summer village, where my husband has lived since 1927, closes down after Labor Day. Nearly all the houses have boarded windows, boats have been taken out of the water and only seagulls cry about the deserted pier where Caroline and I go to throw them bread. The thirteen cousins she played with this summer are all gone. In these lonely Autumn days I follow my husband’s campaign with rapt attention.

“Last week was an exciting one for me and for Caroline. Hurricane Donna came close enough to where we are to knock down ten trees and blow part of the roof away. We really weren’t terribly frightened, but Caroline did worry about what was happening to her father and whether her kitten and puppy were safe. Once she was assured Jack was in Texas where there was no storm, and Kitten and Charley were with us, we spent a cozy evening reading stories by candlelight.

“Jack telephones me late each night. I have been with him in so many of the places he has campaigned this week. That makes me homesick for the days we used to campaign together. . . .”

Ending the letter, and referring to a woman who had stopped her on the street earlier that day and remarked how proud she must feel, being the wife of a Presidential candidate, Jackie concluded with these touching words:

“I am not sure I share the supposed dream of American women—to see their sons be President, or one’s husband. Being President is one thing; you could not help but be proud of that—but running for the office is another; an ordeal you would wish to spare sons and husbands. You worry and wish you could diminish the strain, but of course you cannot. Perhaps it is fitting that the highest office in the land demands the severest effort. . . .”

September 1961-1962

This was the ninth year of their marriage, and the year that is now drawing to a close.

Politically, it has been an up-and-down year for Jack Kennedy (with the accent seemingly on “up”).

Domestically, it was probably the happiest year of their lives. Aside from Jackie’s trip to India—at the invitation of Prime Minister Nehru, and with Jack’s blessing—they were rarely ever separated.

“In fact,” as someone has written, “with the President working in the same house where he lives—it would be hard for him and his First Lady to be separated for any real length of time.”

And this seems to have suited Jack and his Jackie just fine. They have—to the horror of some, but the delight of most—been seen holding hands while walking down White House corridors together.

They have entertained lots and seen to it that there was more dancing than ever before in White House history at their receptions—almost, it appeared, so that they could share an extra dance or two.

They are the parents of two beautiful and seemingly unspoiled children. . . . The President has his health back. . . . Jacqueline Kennedy has hers. . . . They are both young and good looking. . . . They have, in short, just about everything!

But most of all they have their love.

And we’re sure that millions of others join us in saluting this love of theirs—now—as this tenth year gets under way.

Because they will need their love in this year ahead, more than ever—as dark and atom-spiced clouds make what should be the summer of our civilization both gray and hazy; as the peoples and the nations of this world seem to fall more and more out of love with one another.

Next Year?

The tenth year may be the most critical, the most challenging of all.

The personal pressures they are both being forced to bear suddenly seem overwhelming. Things get rough after a while for the man who holds the most important job in the country. It happened this way to presidents right down the line.

It’s happening, right now, to JFK.

Though his personal popularity with the people remains enormous, he has political problems that seem just as enormous. In the last few months alone he has seen his farm bill defeated, his education bill murdered, his Medicare Bill voted down. Added to all this—he has lost more than a fistful of support from many businessmen who once smiled happily at the words New Frontier—men who are now irreconcilably bitter over the steel showdown which the President enforced.

And, of course, the stock market has taken its sweeping dive.

And, too, all indications are that the Republicans are growing more and more confident about their chances of victory in the elections next month.

As one observer puts it: “At mid-term, Kennedy has to answer the question that faces the flashy rookie in baseball after July Fourth. Has he got it or hasn’t he?”

As for Jackie, she’s getting her share of the woe-pile, too. Her good looks, her clothes, her innate elegance—all the things about her that so charmed the entire nation at first, now seem to be taken very much for granted.

Now—after nearly two years—the reverse reaction is beginning to set in . . . the whispering campaign . . . the criticism.

She’s criticized suddenly for allowing too much publicity to be centered around herself—and her children. . . . She’s criticized suddenly for the “egghead” parties she’s been giving at the White House. . . . She’s criticized for not having attended her husband’s birthday gala in New York’s Madison Square Garden last spring. . . . She’s criticized for having spent this past summer in Newport, Hyannis Port—not to mention that stay in Italy! “Most of it,” as the whisperers whisper, “without him!”

And as her husband’s job becomes tougher this next crucial year, the criticism of Jackie may become louder.

But in adversity—especially when shared—there is strength. And with love—all troubles are dwarfed.

Love, in its highest and sweetest and most beautiful sense, Jack and Jackie Kennedy have.

Nine years of love behind them.

A tenth year and, God willing, many many more years of love—ahead.

THE END

—BY ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023I really appreciate this post. I’ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thx again