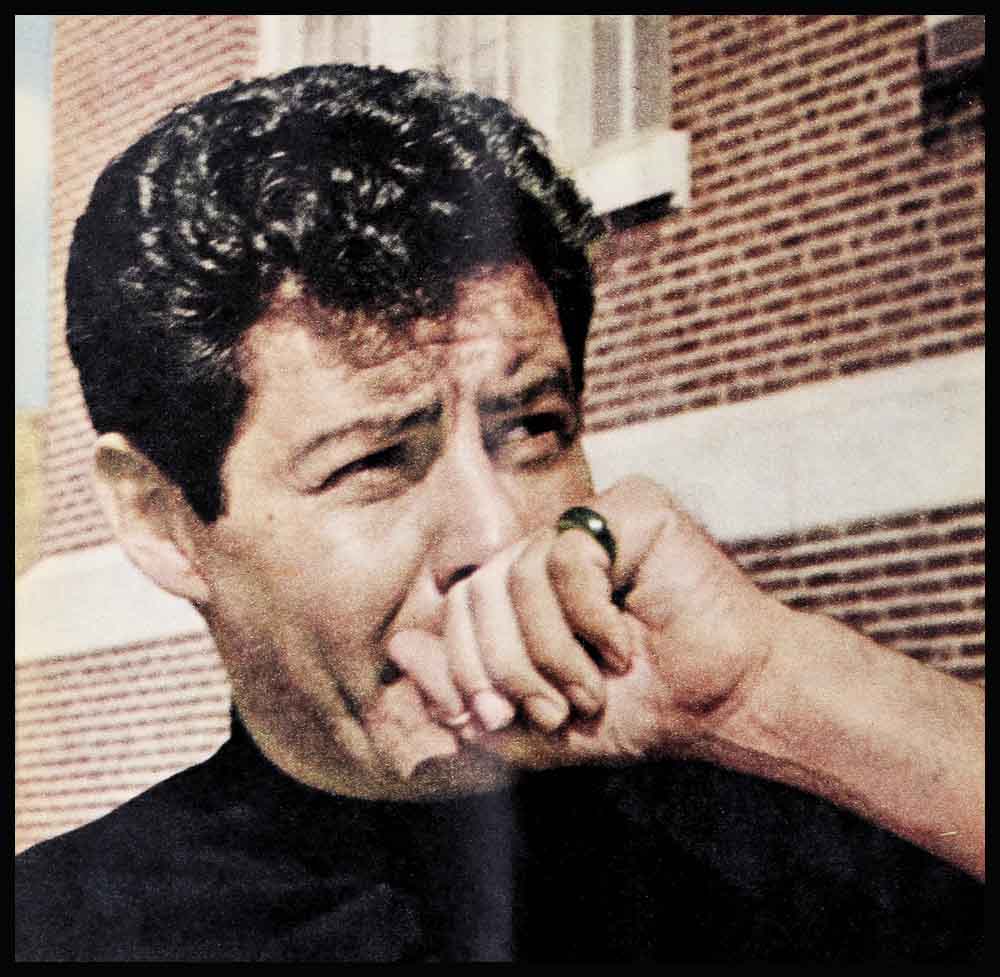

Eddie Fisher’s Paralysis

This is the story of a man running—running from the woman he once loved, running from the woman who hurt him, running from the dream that died.

And running, running from accepting the truth: He loves her still.

This is the story of Eddie Fisher and Elizabeth Taylor today.

If you’re wondering how Eddie has weathered this one-year period of rugged, enforced adjustment after the Roman Scandals of 1962, you have only to look at his string of feverish engagements over the past year. Clearly, Eddie was a man on the run. He filled every moment of his time with work and more work. He needed to keep busy. He needed his career. He needed to stop thinking. This was the battle to win himself a new life.

Right now, looking at Eddie—tanned, exuberant, bursting with plans to produce a movie in France with Natalie Wood. having dates with Eddie Adams and other attractive darlings in the cinemacenter, you would think he’s doused his torch for Liz.

But that surface show. as you very well know, is not always a true barometer of the climate of the heart.

Let us flashback, shall we, to April, 1962: Eddie arrives unexpectedly in New York as rumors in Rome are flying. His trip is reportedly business. He accepts no phone calls, ducks the press, opens his door only to his doctor. Days pass. No sign of Eddie. Meanwhile, back in Rome. Liz is flaunting her affair with co-star Richard Burton quite publicly. Eddie is panicky. 20th Century-Fox is panicky. Mrs. Burton is panicky. The press is undaunted. They haunt the Hotel Pierre, the elevators, the 76 back exits. They try to pass themselves off as hotel staff.

Finally, Eddie’s public relations outfit—a Hollywood-based firm with an arm in New York, decides that it is time for Eddie to face the music. They call a press conference to straighten out the wild rumors and confusion surrounding his trip to New York and the status of his marriage to Elizabeth.

Shaking from lack of sleep, looking very much like a victim of a concentration camp, visibly on the verge of hysteria, Eddie enters the room. The reporters charge at him with questions. He tries to parry the answers. Finally they back him into a corner from which he cannot possibly escape. Is his marriage to Liz over?

Six thousand miles away Liz enters the skirmish via transatlantic phone. She can save Eddie with a word. “No,” she could say, “our marriage is not over.” But the lady does not choose to say that no. She refuses to uphold Eddie’s denials and the studio-released fiction that all is well in the Fisher household on the Via Appia in Rome. From Numero 7990528 in the pink villa, comes the tinkling bell of her voice—and it tolls the death of a marriage.

Eddie puts the phone back on the cradle—crushed in ego, spirit and energy. He ends the interview by telling the press—“the lady has changed her mind—I guess that’s show biz.” The ill-starred interview is televised and re-televised all that night.

Hollow-eyed Eddie, in a quandary of uncertainty as to his marital fate, waits for the early-morning papers to see what new developments have taken place on the other side of the world. He is not disappointed in his expectancy. Full-page blow-ups of radio-photos from Rome decorate the front pages of every newspaper. The photos show Eddie a cozy close-up of his wife in the snuggling, apparently unashamed embrace of Richard Burton—the married father of two.

If Elizabeth’s non-committal conversation over the phone hadn’t already hurt Eddie terribly, these photos—immediately on the heels of that interview—killed that one small glimmer of hope he held that somehow things could still be made well. Now he knew the truth.

A few days later Eddie Fisher went into an emotional tailspin that brought him frighteningly close to a complete nervous breakdown. And worst of all, now it can be revealed. he fought a frightening bout with a paralysis of his left side. The paralysis was, apparently, a result of his emotional problems. Heartbreak had crippled Eddie Fisher. Still, he managed to hang onto reality. He knew he needed help.

In deep pain and confusion, he was rushed to a hospital for specialized care. He had not slept for weeks—he had eaten barely enough to keep alive and his friends were alarmed at the weight he lost. His manager tried to protect Eddie over that touch-and-go period. but the press hounded him in an effort to find out just what was going on.

If it were not for the skilled Services of Dr. Max Jacobson. that well-known restorer of scores of famous people, Eddie might very well have gone over the edge.

Through the use of relaxing and antidepressant drugs, Dr. Jacobson coaxed Eddie into the only possible therapy—that of talking out his conscious and subconscious thoughts. He spoke of all that had happened to him in Rome . . . all that had happened before he fell into the grip of hysterical paralysis.

Ordinarily a reticent conversationalist. Eddie began to respond to the doctor’s probing. He began to understand the nature of his ailment and the only hope for its cure. He regained his confidence and then, almost as if in a hypnotic trance, he began to crystallize his tortured thoughts into words. What thoughts and what words they must have been! Violent, hating, revengeful, self-pitying.

A torrent of feelings poured forth from his pain-wracked mind and body. Dr. Jacobson told Eddie that by stifling any of the humiliation, frustration and hostility he felt over his marriage, he was doing real, physical damage to himself. The treatment was for Eddie to talk non-stop until the early rays of many mornings, first in New York and later in Beverly Hills. And Eddie talked. He spewed out the poison that infused his every pore. that had shrunk him physically and mentally and visited upon him this dreadful, sudden paralysis.

Skillfully, Dr. Jacobson helped Eddie face his hurt. Even when the doctor was summoned suddenly to another patient in Washington, he refused to abandon Eddie. He had him bundled into the same plane and secreted in his hotel where, after consultations with the other patient. he could continue the talking-out process. It was important to be near Eddie to administer medication and. also. to give him the confidence of his personal attendance throughout the ceaseless seizures of pain.

Through this treatment of realizing all the stored-up hate of these three months of anguish, Eddie found a measure of acceptance and adjustment to the situation he had been forced into. The catharsis of spoken words eased the suffering that overpowered him. After this expiation of hate, Eddie knew the truth—he still loved Liz. He found that no matter what the dictionary says. hate and love are really one, and hate is often proof of unqrenchable love. Eddie learned then that you cannot hate someone you do not love. and with his new-found knowledge, his paralysis left him as abruptly as it had attacked him.

Nothing—not the pain he suffered nor the rage he felt—could change the deep and abiding passion Eddie felt, still feels and will always feel for Liz Taylor. For she had captured his imagination long before he became famous, long before he became wealthy, long before he married Debbie Reynolds and long before he acted as best man at her third marriage in Mexico. And she captures his imagination even today.

Eddie, it appears, has come to terms with the fact that he cannot douse his torch for Liz—control it though he might by his new maturity.

With this realization under his tightened belt. Eddie turned himself outward again to face the world. He threw himself into his career with a never before felt fervor and enthusiasm—grateful for an opportunity to sing his heart out and to be taken back into the hearts of the public that had forsaken him.

He woke up each morning with happier thoughts. He greeted the world with a bright expectancy. He ate heartily, and he slept soundly without the need of drugs or drink or the fear of nightmares. He explored New York all over again or as if he had never seen the big city before. He visited with friends, and they visited with him.

Then it was time to fly to California, to rent a big house with a small pool, to he with his children, to prepare for his reentry into show business without the showpiece of a wife at his side.

On comeback night at the Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles, Eddie brought the star-studded audience to its feet—and the wildly applauding audience brought tears to Eddie’s eyes. They were the happiest tears of his life—just as a month earlier he had broken down and cried the saddest tears of his life. The recent months of his life seemed to come to a full circle that night. He was himself again!

Next stop. Las Vegas. Then on to Sinatra’s Cal-Neva Lodge in Lake Tahoe. Back to New York and a hurried trip to London. (Not to see Liz as rumored but to confer with Mel Ferrer, of all people, about plans for his night-club act.) After that. Eddie scored another success in another big city—Chicago—doing SRO business for three solid weeks. Then came Labor Day weekend. Eddie had two free days to rest. So he “rested” at Grossinger’s Hotel in New York State by starring in a show commemorating the thirteenth anniversary of his discovery.

From there. he returned to his home town—Philadelphia. There. as everywhere else he was mobbed by fans and friends and his appearance at the Latin Casino broke records for the year. It was reunion time again for Eddie and his old school pals and he was able to give them the time and attention he could not have given them had his wife been at his side.

During the engagement at the Latin Casino, Eddie juggled rehearsals and tryouts for that really big show—the dream of his career—an engagement at New York’s famous Winter Garden.

The dream became a reality on October first. He played to a swank. black-tie opening night sellout. Life Magazine even posted a photographer in Eddie’s dressing room, having been tipped off that Liz was enroute from Switzerland for Eddie’s Broadway opening. The fact was that Liz and Eddie had discussed the possibility of her visiting him on a trip she thought she might make to the States. But it had nothing whatever to do with opening night, and of course anyone who had a thread of interest in Eddie’s personal and professional welfare would have advised against such a foolhardy spectacle.

The realization of his career dream sustained Eddie through the five record weeks at the Winter Garden. And at the stage door, whenever he entered or left, there was always a crowd waiting to get a glimpse of him. to shake his hand, to smile and ask for his autograph. Their acceptance meant a great deal to Eddie.

He was so successful he could even publicly poke fun at himself for the world to see. “You know,’’ he said. “everybody in show business has a side line. Sinatra has a night club or two. Crosby is in the orange juice business, Dean Martin has an Italian restaurant . . . and me . . . I’m thinking of becoming a marriage counselor.” And when there were a few wisecracks that “he got what he deserved,” Eddie helped direct the arrow to its mark —with a laugh.

As the Winter Garden engagement came to a close near the end of the year Eddie made plans to return to California for a badly-needed rest. The public hadn’t known it, but many times his doctor had to confine him to his quarters, no visitors allowed. so that Eddie could get some relief from his schedule.

Now it was time to relax in California. Now it was time to be with his daughter and son for uninterrupted days and nights.

That was how Eddie lived through the year 1962—the year he’ll never forget as long as he lives.

And then came 1963 and the holiday season. Now there was the excitement of parties and dates with Eddie Adams, Juliet Prowse and Ann-Margret. There was a new romantic excitement into Eddie’s life.

Suddenly it was time to plan “The Gouffe Case”—a French murder mystery which he hopes to produce this year with Natalie Wood starring. He threw himself into work again and, then, he took off for a singing engagement in Puerto Rico. He had learned to keep the days filled with travel. with work, and with fun. He knew all these things were necessary to him . . . to blot out any possible relapse back into that melancholy depression when paralysis threatened his well-being and his sanity.

So have the months paused for Eddie, as he works at dousing the torch for Liz. He has succeeded fairly well—considering his addiction to her charms. Even his occasional phone talks with Liz. in which they discuss the weather, industry gossip, the children, and their respective careers, are part of Eddie’s therapy, part of a plan to “kick the Liz habit.’’

Hearing her high. thin voice—like that of a beloved child—sprinkled with witticisms and a sauce of vulgarity as it crackled over the cables also undid some of the recuperation Eddie worked at so hard. For Elizabeth still has the power to hurt him.

He can’t help himself. Nothing can stop the thrill that fills him whenever he thinks of or talks with her.

So, though be may have almost entirely succeeded in keeping Elizabeth from trespassing on his conscious mind, he can’t altogether erase her from his memory. That is how his heart beats and nothing can change this feeling for her.

Does this mean that Eddie would go back to Liz if she cannot accomplish her avowed desire to “marry Burton if it’s the last thing I do on earth?” Deep in his heart, this must have occurred to him.

And though it is unlikely that a man would willingly once more put himself through hell—all things are possible to a passion like his.

While Eddie dates Ann-Margret. a bright and sweet child-woman and Eddie Adams, an understanding and worldly-wise woman. they are not substitutes for the bittersweet ecstasy of his three years of marriage to Liz. Neither of them—and no other living woman—can ever kindle in Eddie the fires of passion that Elizabeth stoked so effortlessly.

On what might very well have been their fourth anniversary this May, 1963, Eddie and Liz might be together again—not as man and wife but as friends discussing picture projects and children.

Or it may very well be that by then the impasse of Burton. Liz and Sybil will have resolved itself one way or the other. Either Liz will win or Mrs. Burton will. And then what will happen to Eddie?

Something’s got to give.

Or someone.

And friends of his can only hope it won’t be Eddie. . . .

—Winifred Ward

Eddie sings for Ramrod Records.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1963